The rise of protest politics - a comment on David Marr's Quarterly Essay

David Marr's Quarterly Essay, The White Queen, captures the highlights of Pauline Hanson's career well, but the focus on Hanson overlooks a much bigger picture - political discontent in Australia’s regions is not new. The…

Essay published in The Quarterly Essay, June 2017

Pauline Hanson is a mesmerising figure. Her political comeback rivals Lazarus with a triple bypass. Her distinctive opinions provide fresh copy for media.

David Marr’s Quarterly Essay, The White Queen, eloquently captures the highs, lows and more recent highs of Hanson’s career. And he uses the Australian Election Survey to dissect her support base: Australian born, trade-educated, opposed to migration.

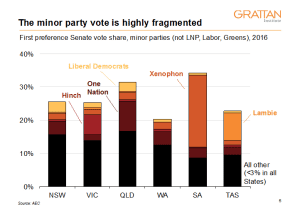

But this focus on Hanson overlooks a much bigger picture. In the 2016 federal election, minor parties – that is, not counting Labor, the Liberals, the Nationals and the Greens – gained 26 per cent of first preference votes in the Senate up from 11 per cent in 2004. A good chunk of the electorate is manifestly unhappy, and increasingly voting for “anyone but them”.

Hanson is benefiting from this rise in support for anyone other than mainstream parties. But she is a relatively small part of the trend. Nationwide she picked up only 4 per cent of the Senate vote. Even in her power-base of Queensland, Hanson won less than a third of the minor party vote.

Part of the minor party vote depends on name recognition. In Victoria the lion’s share went to Derryn Hinch; in South Australia to Nick Xenophon, and in Tasmania to Jacqui Lambie. These parties were barely visible outside their “home” State.

Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party may well implode again. As The White Queen documents, the flaws that led to defeat in 1999 may replay two decades later. But the rise of minor parties is likely to continue – it’s bigger than Hanson.

What explains this turn away from our established political parties?

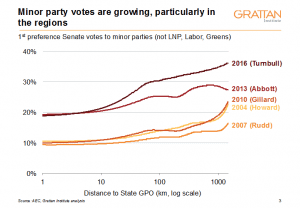

Minor parties do well in regional areas, and they’re getting stronger. In 2016, minor parties polled roughly 35 per cent of Senate first preference vote in the regions, up from 15 per cent in 2010. This pattern holds across all States: the minor party vote grows as one travels further from the state’s capital.

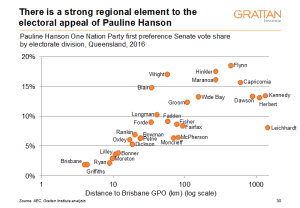

Hanson is part of this pattern. Althoug she has supporters in the cities – and they contain most of the population – her Senate vote in 2016 was strongly regional. She won less than 4 per cent of the vote in the six electorates within 12 kilometres of the Brisbane GPO; she won more than 10 per cent of the vote in eight of the nine electorates more than 100 kilometres from Brisbane (the exception was Leichhardt which covers Cape York and Cairns).

Political discontent in Australia’s regions is not new. As Judith Brett showed in her 2011 Quarterly Essay, Fair share, regions have long resented their lot in Australian politics. Despite the mining boom, cities are growing faster than regions. Many regional areas are losing population, as regional towns grow only by draining population from their hinterland.

But it’s not obvious why these economic trends should translate into different politics now. The past decade simply continues the population trends of the previous century. And income growth per capita has been almost identical in cities and regions over the last decade. In contrast to the United States, those remaining in Australia’s regions aren’t doing too badly.

Nor is it obvious why race should translate into different politics now. Hanson’s resurgence, and the continued rise of other minor parties, does not coincide with any obvious increase in concerns about migration. Marr reproduces the Scanlon Foundation survey answers on attitudes to multiculturalism, and Muslims. Neither has changed materially over the past five years. In the AES, the belief that “immigrants increase crime” has fallen over 15 years, in both cities and regions. And belief that “immigrant numbers should be reduced” is well down from its peak in 2010.

It may be that feelings of insecurity – perhaps motivated by sluggish economic growth and the constant discussion of terrorism – have led some people to close ranks, and to resist the “other” more. Such explanations of outsider politics are gaining currency in the United States and elsewhere, often drawing on Karen Stenner’s book, The Authoritarian Dynamic. People are more likely to have such “authoritarian” attitudes if they particularly value community belonging, and have lower levels of education – both more prevalent in regional areas. In these regional areas, where the share of the Senate vote going to Hanson and other minor parties is highest, migrants are more likely to be seen as “other” because few migrants live there. Ironically, every time mainstream politicians emphasise the threat of terrorism, they may be promoting the rise of minor parties.

Anti-migrant sentiment is not the only dynamic behind the spectacular rise of minor parties. Even though concerns about migration are much lower in the large capital cities, minor parties are also gaining traction there. Many of the growing minor parties such as Derryn Hinch’s Justice Party and the Nick Xenophon Team do not play the politics of race that are core to Hanson’s appeal. Voters for minority parties other than One Nation favour migration at least as much as LNP voters.

Instead, many minor parties are appealing primarily to falling trust in government and politicians, as documented by the Australian Election Study and the Edelman Trust Barometer. As Donald Trump put it, voters want to “drain the swamp”. Confidence in institutions is falling even among those comfortable with migration. Around the globe – and in Australia – minor parties vary in their attitudes to migration, to free trade, to size of government, and to inequality. But all of them explicitly claim that establishment politics is no longer serving the public interest. And this claim clearly has electoral appeal.

The biggest challenge to established political parties is not Hanson’s politics of race. It is her participation in a much bigger anti-establishment movement that challenges traditional political parties to rebuild voter trust in government. In many countries, this movement has reached the threshold where it can win elections. In a democracy, if governments lose the trust of the electorate, then electorates will ultimately rebuild governments.

Essay published in

Essay published in