Published at The Conversation, Tuesday 20 August

Inheritances can have an enormous impact on finances and lives.

Yet in Australia we know surprisingly little about who gets them and how big they are.

New Grattan Institute research provides some answers.

A sample of estates from Victoria’s probate office suggests the median estate in Victoria is worth around A$500,000. That’s likely to be close to what it is Australia-wide.

But many are much larger. About 20% are worth more than A$1 million, and 7% are more than A$2 million. Property is the largest component, accounting for about half of the average value.

The main beneficiaries of “final” estates (estates without a surviving spouse) are children, who receive about three-quarters of all inheritance money.

Other family members, such as nieces, nephews and grandchildren, receive about 20%. Friends get about 4%, and charities 2%.

Average inheritances are growing about 2 percentage points faster than inflation each year, which is a good deal faster than wages or gross domestic product.

There are reasons to believe they will soon grow even faster.

Net wealth has grown strongly among older households. Households headed by people aged over 75 now have an average of A$1 million in assets, up from A$400,000 for a household headed by a person of the same age in 1994.

And most retirees don’t draw down on their savings.

Indeed, many are net savers through much of their retirement, meaning there’s only one place their accumulated property and superannuation wealth can go: into bequests.

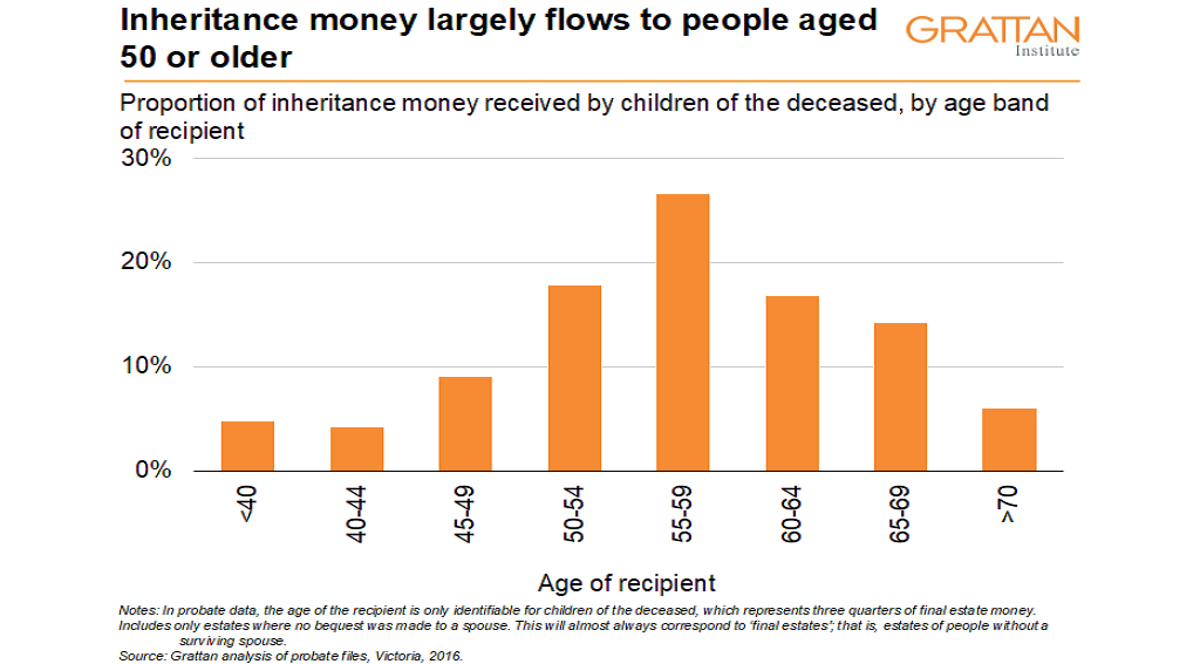

These days, inheritances generally don’t arrive when people are saving for a house or trying to raise a young family.

More than 80% of money passed down from parents goes to people aged 50 and over.

The most common age bracket in which people to receive an inheritance from parents is 55-59.

It’s the result of good news – parents are living longer.

But as life expectancy grows still further, it will mean inheritances increasingly supplement the retirement savings of middle-aged Australians rather than help young people get into housing.

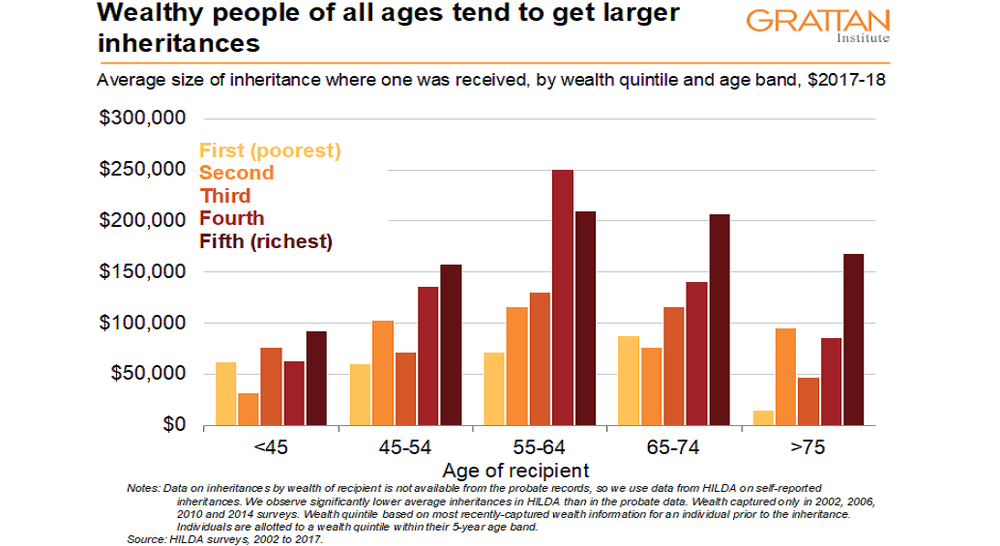

The wealthiest 20% of Australians get 38% of inheritance money; the poorest 20% get only 8%.

It means the growing wealth of Baby Boomers is likely to end up concentrated in the hands of a select group relatively well-off Generation Xers and Millennials rather than being widely spread.

It will reinforce the advantages already enjoyed by people with well-off parents, including better schooling, better connections, and a greater ability to take financial risks because of a parental safety net.

If (as is possible) inheritances end up becoming the dominant route to wealth in Australia surpassing lifetime earnings, there will be less incentive for ordinary Australians to attempt to get ahead through individual endeavour.

We will have entered what French economist Thomas Piketty calls a “Jane Austen world”.

Calm debate on policy setting around inheritances is hard to come by in Australia.

Inheritances and gifts have been tax-free since the 1970s.

Australia is one of only seven OECD countries without any inheritance, estate, or gift taxes. Despite the economic arguments for inheritance taxes, there seems to be little appetite to bring them back.

Not taxing inheritances is one thing, but actively subsidising them is another.

Superannuation tax breaks were intended to encourage people to save for their retirement and to take pressure off the age pension system.

But given that many retired Australians do not draw down on their capital, a large part of the super tax concessions simply boosts the size of bequests.

Super death benefits tax is intended to claw back the superannuation tax breaks when the money is passed on, in order to ensure that the government doesn’t subsidise inheritances.

But, at 15%, the rate is too low to capture the value of the accumulated tax breaks. And it can easily be avoided by retirees withdrawing funds tax-free and then contributing them back as a post-tax contribution, which is tax-free when passed on.

The special treatment of the family home in the age pension means test also acts to boost inheritances at taxpayers’ expense. Without it there would less to pass on.

There is little justification for taxpayers subsidising inheritances. Policy changes could help.

We recommend a higher tax on super bequests paid to non-dependents to better capture the value of the super tax breaks that are passed on rather than used for retirement. The cap on post-tax super contributions should also be lowered, to limit the re-contribution strategies.

The age pension assets test should include part of the value of the family home, perhaps the part above A$500,000. Seniors with higher-value properties should be allowed to borrow against their home using the Pension Loans Scheme.

This would give them the ability to stay in their home but would mean that some of the wealth that would otherwise be passed to heirs (most likely in their 50s) would instead be used to fund them, taking pressure off the pension.

![]()