I’m delighted to be invited to give this address and to set the scene for what I hope will be two days of robust conversation and forward policy momentum.

It is right that we open with a focus on full employment and productivity – somewhat abstract economic concepts yes – but ultimately ones that have a real impact on quality of life for each and every Australian.

Full employment as our economic lodestar

Let me start with full employment.

Right now we are in the extraordinary position of having an unemployment rate with a 3 in front.[1] And that has come alongside the fact that a record number of Australians are working.

This matters.

It means that more people who want a job now have one. It means that some people otherwise at the fringes of the labour market – young people looking for their first job, people with a disability, older workers, and the long-term unemployed – are now seeing doors open in in ways they haven’t in the past.

Full employment also represents pain avoided.

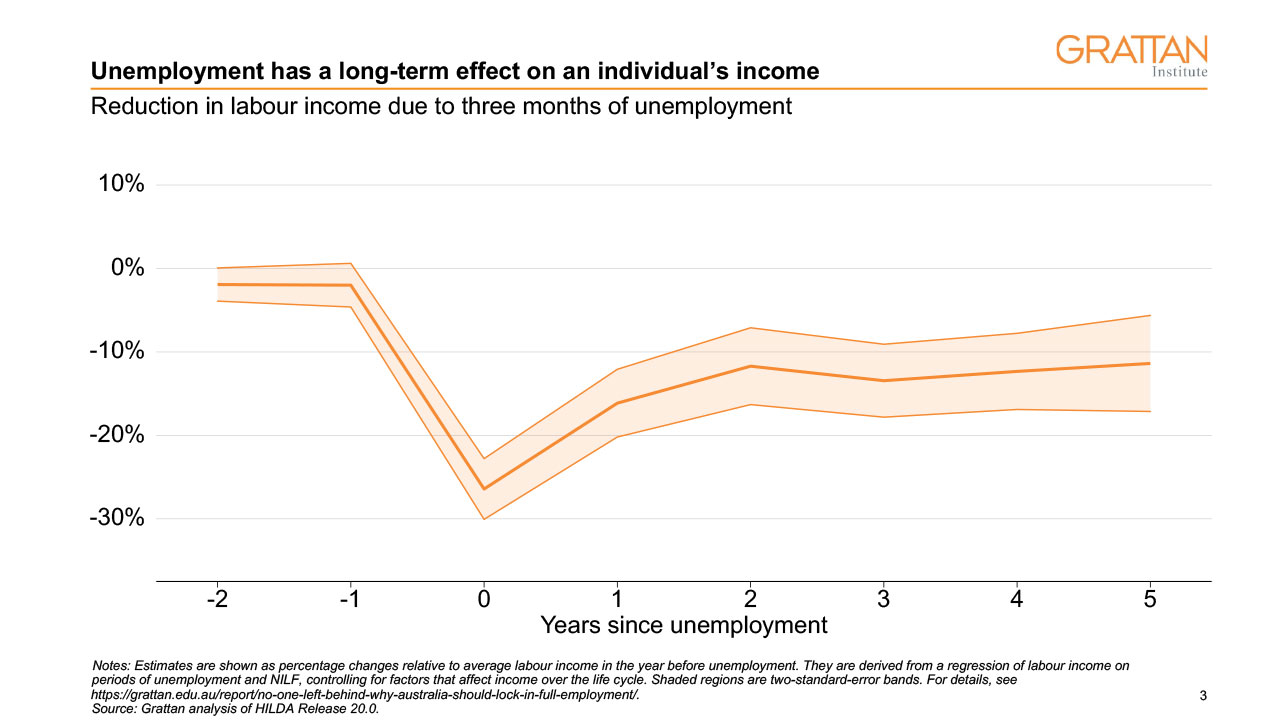

Before COVID struck, the average spell of unemployment was almost a year long. But even just 3 months out of a job is enough to hit people’s earning potential even

many years later.[2] The cumulative effect of a three-month spell of unemployment is equivalent to nearly a year of lost pay.

Tight labour markets mean that people can find new work more quickly and hopefully avoid these economic scarring effects, not to mention the mental and emotional issues that often run hand-in-hand with unemployment.[3]

But the benefits of full employment extend far beyond those who would otherwise be out of work. Tighter labour market conditions catalyse better labour market outcomes for all Australian workers.

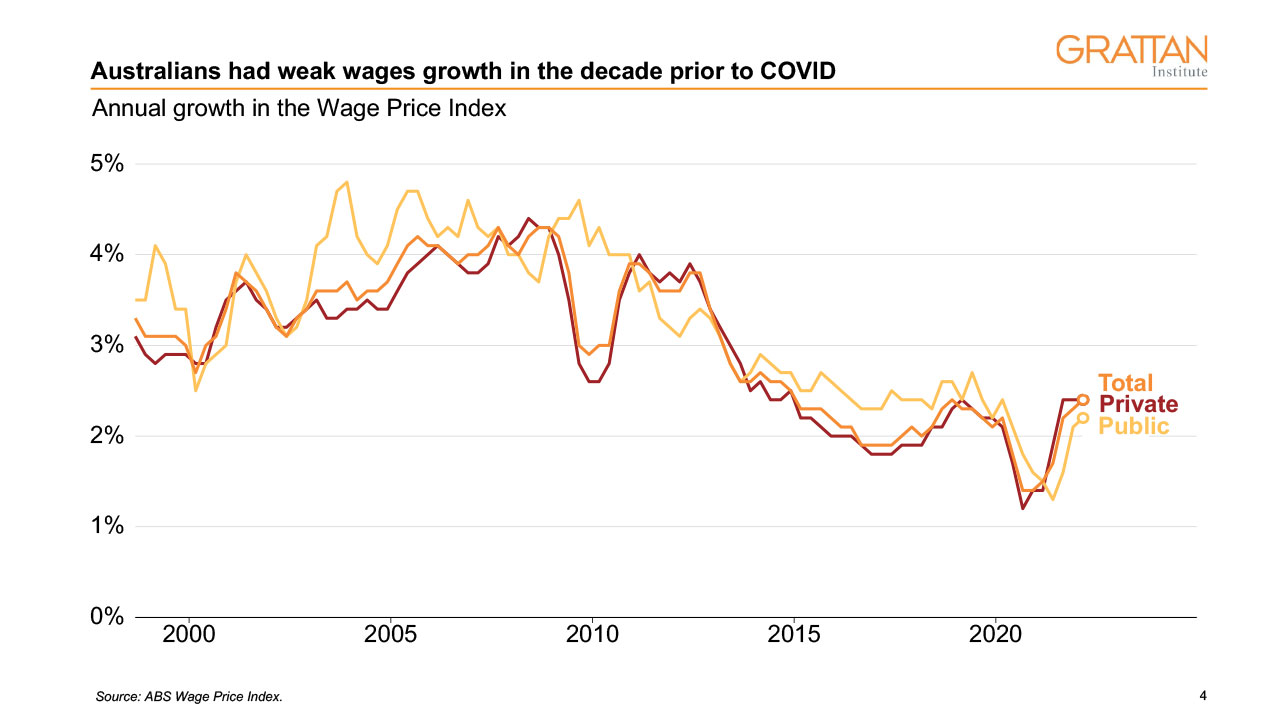

As we know, real wages have been in holding pattern for the best part of a decade. With the current breakout of inflation, they are going backwards. Grattan Institute analysis suggests at least one-third of the slowdown in wage growth in Australia since 2013 occurred because of tepid macroeconomic conditions.[4]

While we may have slightly overshot in adjusting the taps – with things now running a little too hot – pressures will likely dissipate, especially if the federal government and the central bank work in tandem to address strong demand and do what is possible to boost supply across the economy.

But my central point remains: strong macroeconomic conditions and a strong labour market will, over time, translate to higher pay for all workers.

There are of course many things that affect the rate of wages growth, as we’ll discuss over the next two days. But a strong economy with low unemployment is necessary and vital to getting wages moving again.

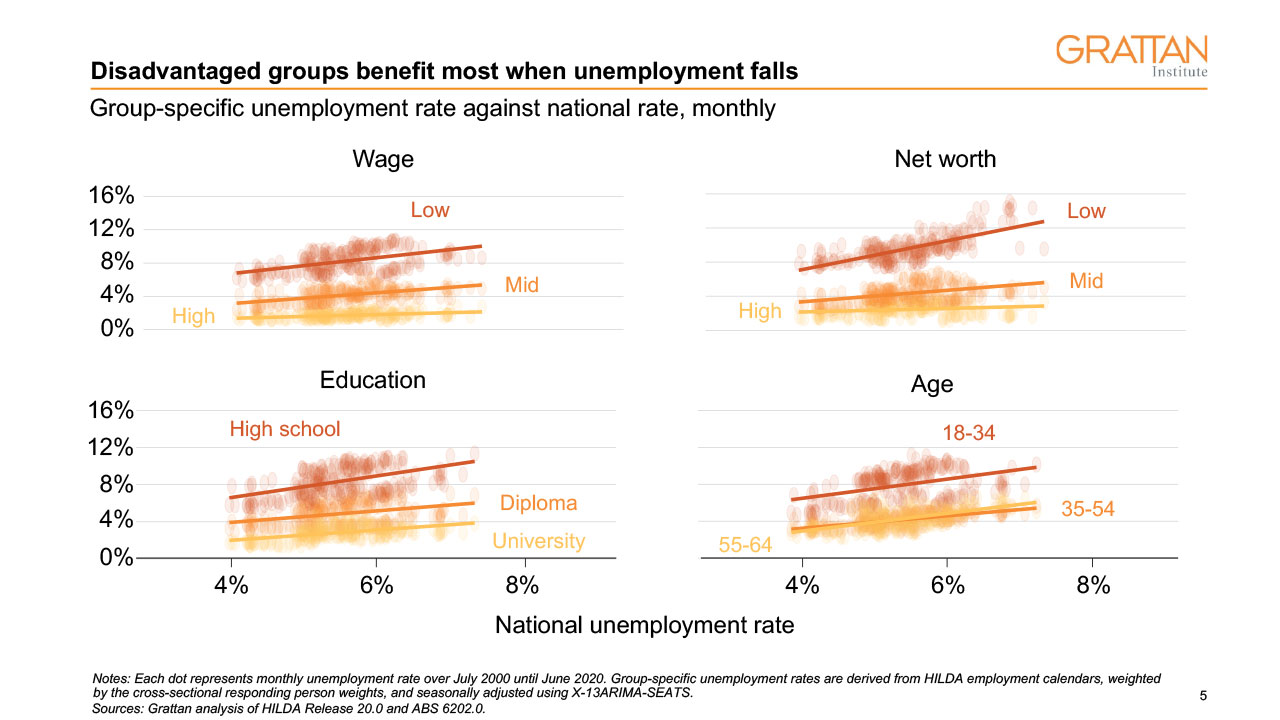

Our work shows that lower-wage and lower-wealth workers have the most to gain. Their unemployment rates fall by more than other groups when the overall unemployment rate is lower. Macroeconomic conditions matter for inequality.[5]

When unemployment is low it lowers the cost of leaving a bad job and finding a better one. This is good for workers but it’s also good for productivity. Poor-performing businesses that survive, not on the strength of their products or services but off the back of exploiting their workers, are driven out. Investments and workers flow instead to better-run businesses.

And when workers are harder to find, businesses have an incentive to invest in new equipment and processes, which ultimately boosts productivity and drives higher living standards.

But when the dust settles on the current unusual period of hot demand and deep upheavals to supply – what will Australia be recovering to? Can we lock-in the benefits of full employment, or will we return to the so-called secular stagnation of the previous decade?

Around the industrial world, the decade sandwiched between the GFC and COVID was one characterised by economic funk. Wages were stagnant, unemployment was elevated, and aggregate demand was weak.

The animal spirits of business appeared to be largely in hibernation. Profits were high and interest rates were low, yet investment was weak, rates of new firm entry and entrepreneurship declined, and so did rates of firm exit.[6]

Whether we can permanently shake that funk depends on the actions of the groups represented in this room.

Can we today agree to make full employment our economic lodestar?

A commitment to strive to maintain full employment is probably the single biggest commitment we could make to deliver better economic outcomes for Australians.

- Maintaining a full employment economy will require a prioritisation of pro-growth investment.

- It will need an emphasis on taking on and training Australian workers – not just abled-bodied, job-ready 30-year-olds, but the younger people reaching for their first job, people with disabilities and older workers who still want to make a contribution.

- And it will require a substantial upgrade of the policy scaffolding from government – especially the enablers – the climate policy, digital policy, industrial relations and human capital-boosting policies – to provide a positive ecosystem for this investment.

Also live is the question of the role of Australia’s central bank and federal government in bolstering demand to maintain full employment. In a world of structurally lower interest rates, what role does fiscal policy have in helping the economy run hot enough to maintain its full employment position? These are issues that are front-and-centre in the current review of the RBA, and indeed in similar reviews around the world. So while the macro policy levers are not in play for this summit, they do form an important backdrop to our conversation.

Productivity growth – it’s not everything, but in the long run it’s almost everything

What is in play here is the issue of productivity – indeed, it is the second headline act of this morning’s session.

While full employment is about making sure we are not leaving Australia’s precious human capital on the shelf, productivity growth is about making the best use of every worker who is employed.

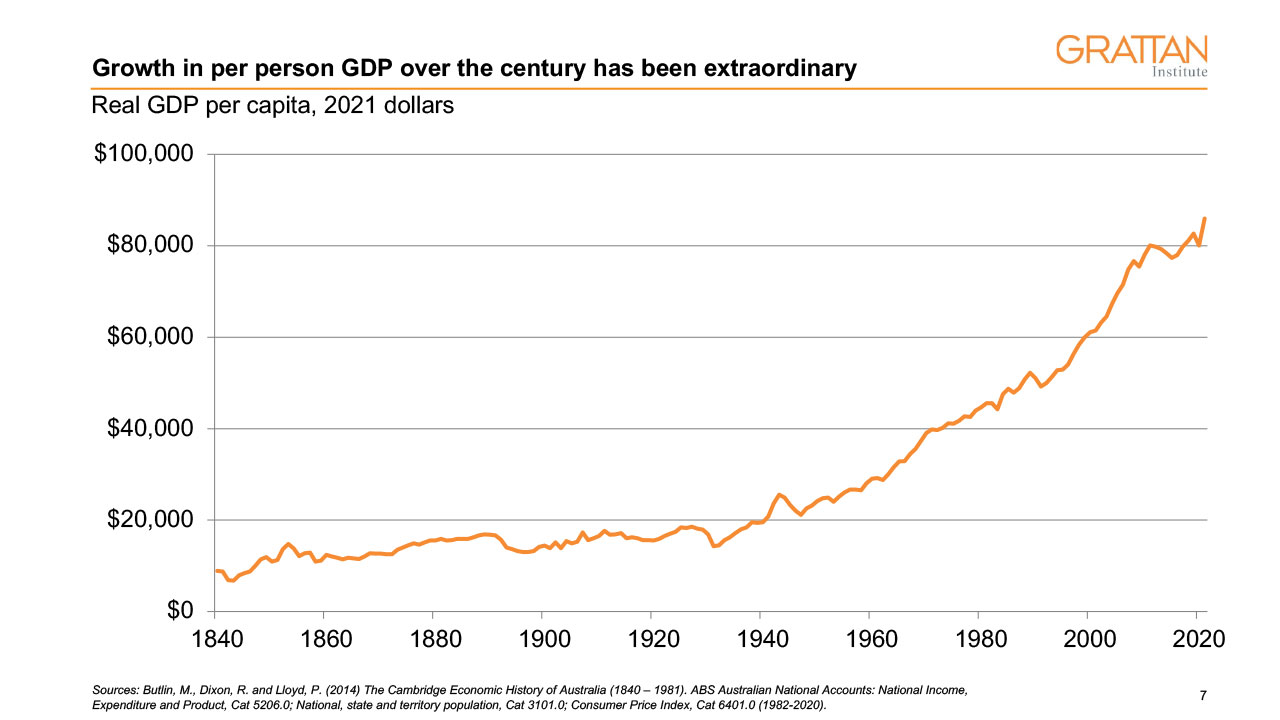

Work smarter not harder may be trite but it has been the defining feature of almost 80 years of extraordinary growth in living standards.

It might be easy to dismiss productivity as the niche fetish of econocrats and AFR journalists, but the recent Productivity Commission report, The Key to Prosperity, makes it clear why productivity matters.

At the start of the 20th Century, life was materially worse than it is today for the average Australian on many dimensions.[7]

Most obviously we had less stuff, with output of goods and services per person at federation less than 1/7th of what it is today. But even more significantly:

- For every 10,000 newborn babies, more than 1,000 died before they reached their first birthday, compared to just 3 in 10,000 today.

- For those who survived childbirth, life expectancy was about 60 years, compared to more than 80 years today.

- During their 60 years of life, the average Australian worked much longer hours, in more dangerous workplaces, and with little access to paid leave.

- Homes were smaller and more crowded – to say nothing of the absence of indoor toilets, dishwashers, and washing machines.

Productivity and wages growth go hand in hand. And while productivity remains the secret sauce of higher incomes, it is worth noting that recent research finds some reduction in the share of productivity gains passed through to workers over the past 15 years.[8]

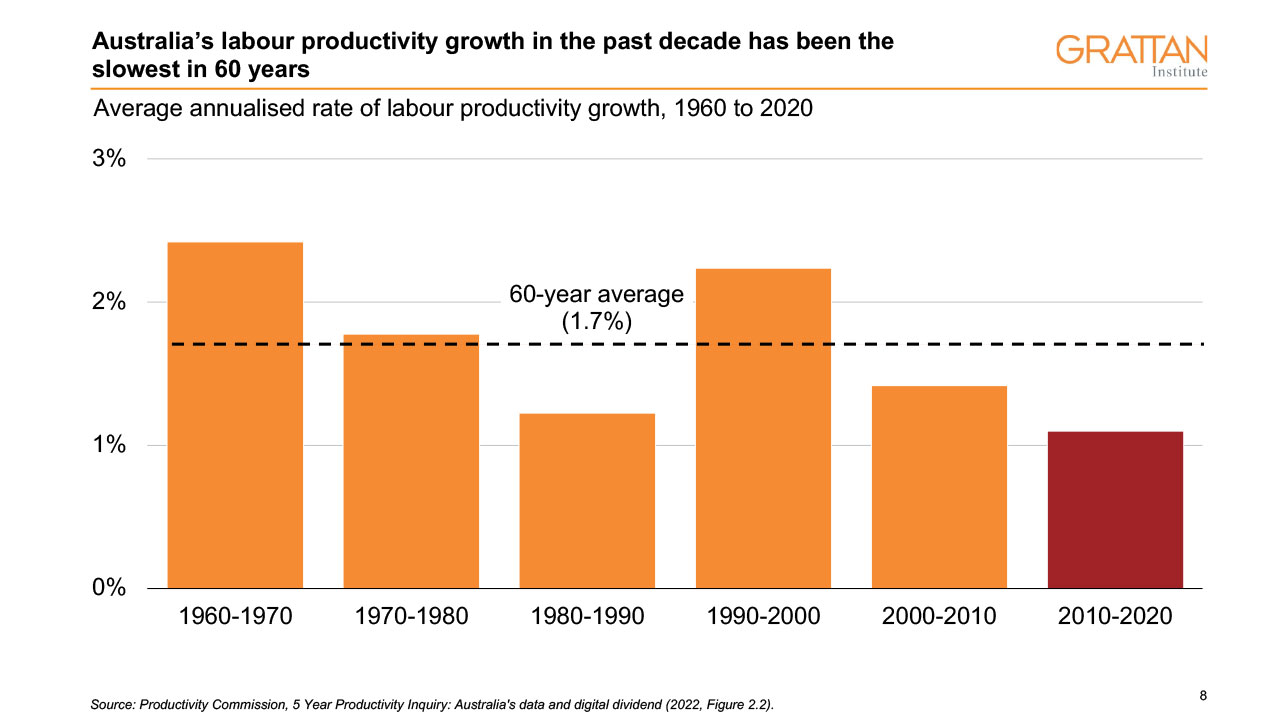

The other thing we know about productivity growth is we have less of it than we used to. No matter how you cut it, the rate of productivity growth has slowed over the past decade.

Over the past 60 years, our labour productivity improved at an average rate of 1.7 per cent a year. Over the decade to 2020, it was 1.1 per cent a year.[9]

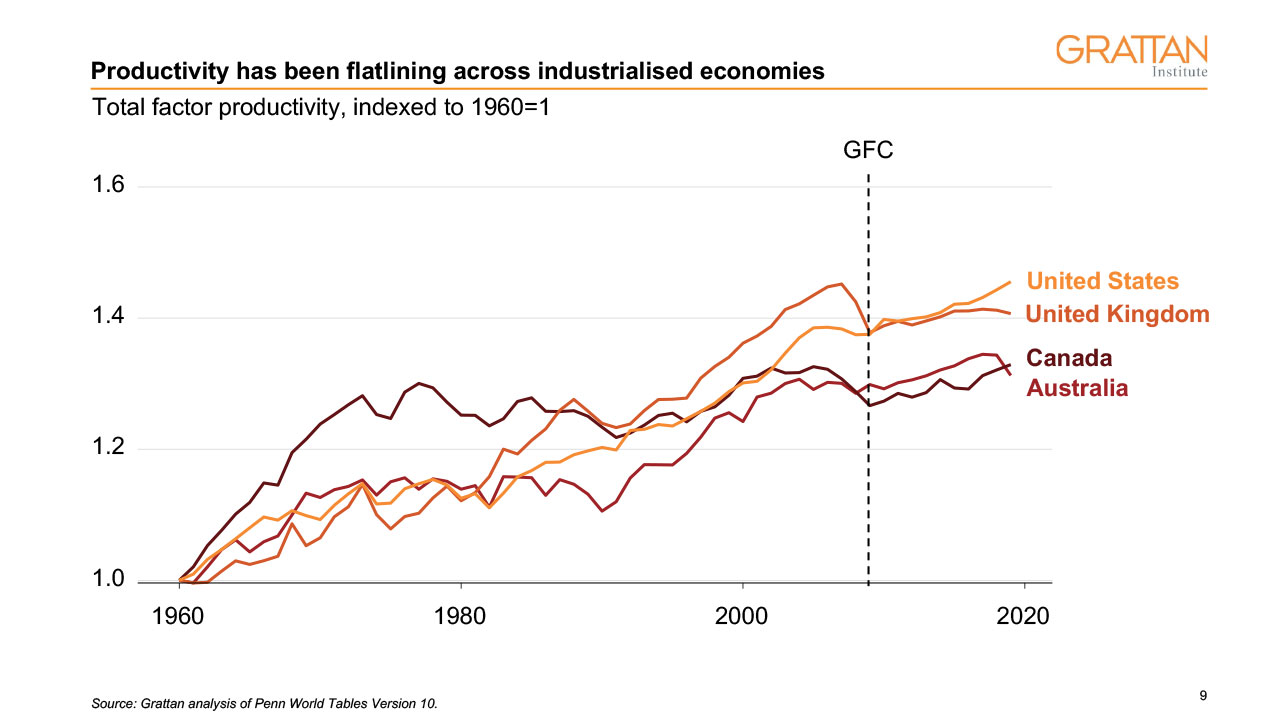

This is not just an Australian phenomenon. The slowdown has been seen around the developed world, although our relative performance has also slid down the international rankings.[10] Everyone is running slower, but Australia is also falling back in the field.

So why has productivity slowed?

There is no single answer, but there is broad agreement on the main explanations:

- expansion of the services sectors, which are generally lower productivity,

- a declining contribution from technological advancements,

- smaller gains from education, as richer countries start to reach saturation point on school completions and the proportion of people going to post-school education,

- a reduction in economic dynamism and, related to that, greater market concentration and power.

But while the whys have been well thrashed over, and the problem admired from almost every angle, this summit is about the whats.

What levers do we have and what commitments can we make as businesses, as unions, as civil society, or as governments – to drive improvements in living standards in Australia for the next decade and beyond?

The changing Australian economy

But before we get there, we need to understand the lay of the economic land and how it is changing.

Too often conversations about economic policy happen in the rear-view mirror. They seek to preserve in aspic previous economic, social, and geographic structures.

This is often an expensive exercise in futility. We cannot push economic water uphill, but what we can do is make sure that we move with the flow and strive to provide good opportunities and jobs for Australians regardless of their location, sector, or personal characteristics.

And while I do not claim to have a crystal ball, I want to touch on three themes of change that will be important determinants of the shape of our economy and jobs in the decades to come.

Theme 1: The march of the services sector

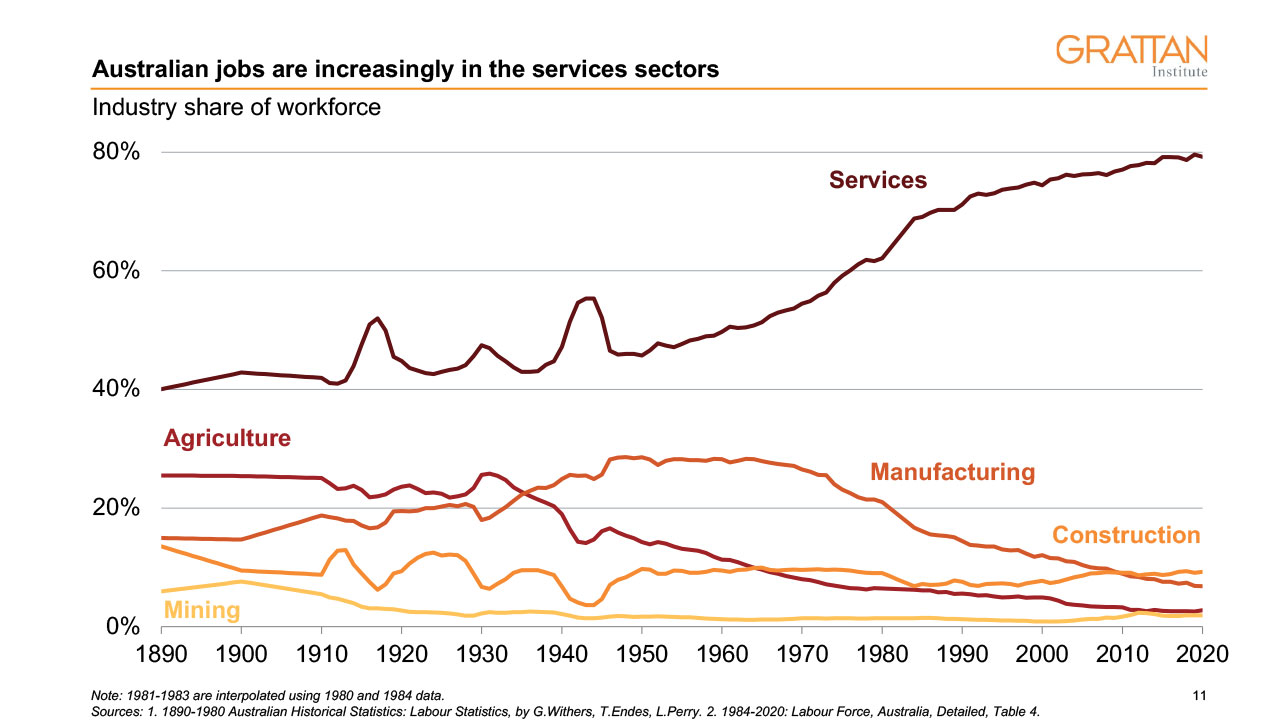

Over the past 100 years the Australian economy has undergone major sectoral transformation: essentially from an economy that made goods – ‘stuff you can drop on your foot’ – to an economy of services.

At the time of Federation, 1 in 4 Australians was employed in agriculture. By 2020 it was just 1 in 36.[11] Manufacturing began its long decline as an employer in the 1970s. But in both sectors, output continued to rise as technological developments meant we could produce more but with less.[12]

The flip side is the extraordinary growth in jobs in Australia’s services sectors. Services now account for around 70 per cent of national economic output.[13] And 8 out of 10 workers in Australia are employed in services jobs.

Services jobs are real jobs. They include our vital health and care workers, our teachers and university lecturers educating young Australians, our scientists and tech workers unleashing the next waves of innovation, and the cleaners, drivers, and administrators who provide the economic plumbing that keeps everything running smoothly.

Despite being an overwhelming majority, these jobs are too often overlooked in public discourse and policy making.

Government responses to economic crises – even services-lead downturns such as the COVID recession – still overwhelmingly emphasise support for the construction and manufacturing sectors. Similarly, government bail-outs, subsidies, and tax breaks for private businesses also weigh heavily toward these sectors.

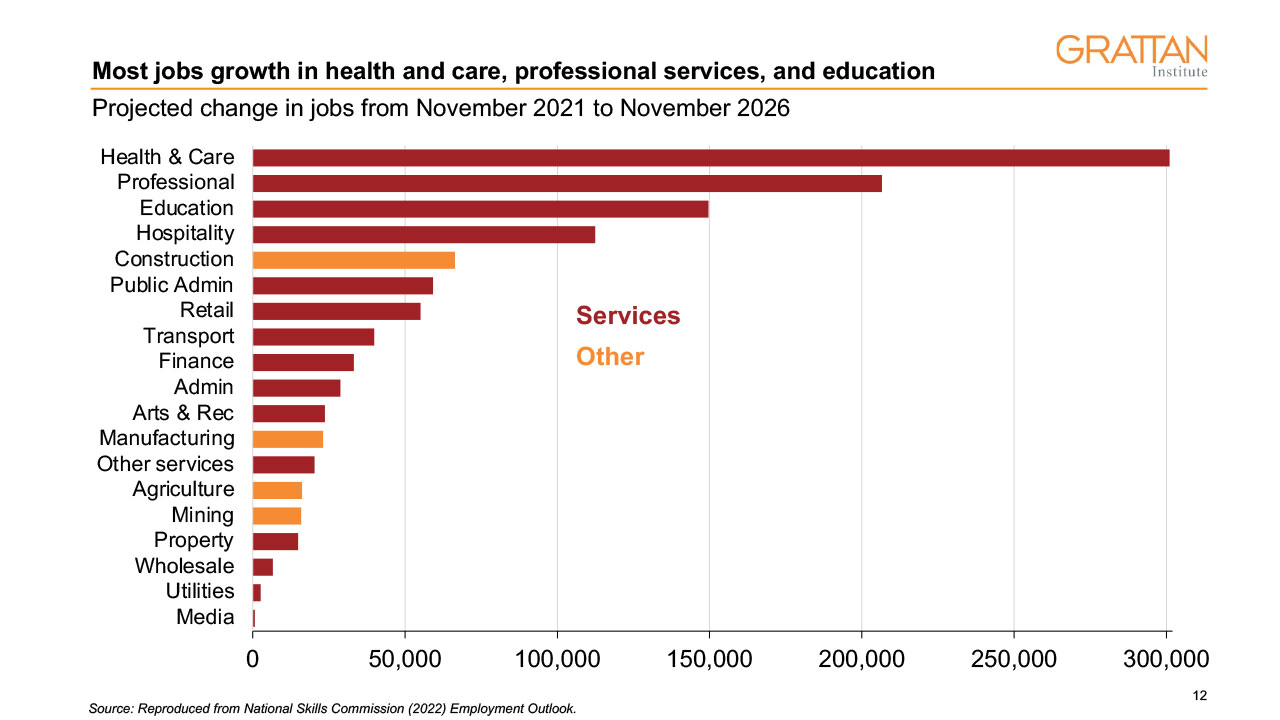

The rise of services jobs is not something to fight against or bemoan as a country; it is a standard evolution of all countries as they get richer. And indeed, it is expected to continue.

Jobs growth estimates from the National Skills Commission suggest health care, social assistance, professional services, and education will be the biggest growth areas over the next 5 years.

And I think it would be a very fair reading of history and demographics to expect that these trends will continue.

Theme 2: An industrial revolution with a deadline

Australia’s economy faces transformative change to meet global and domestic emissions-reduction targets.

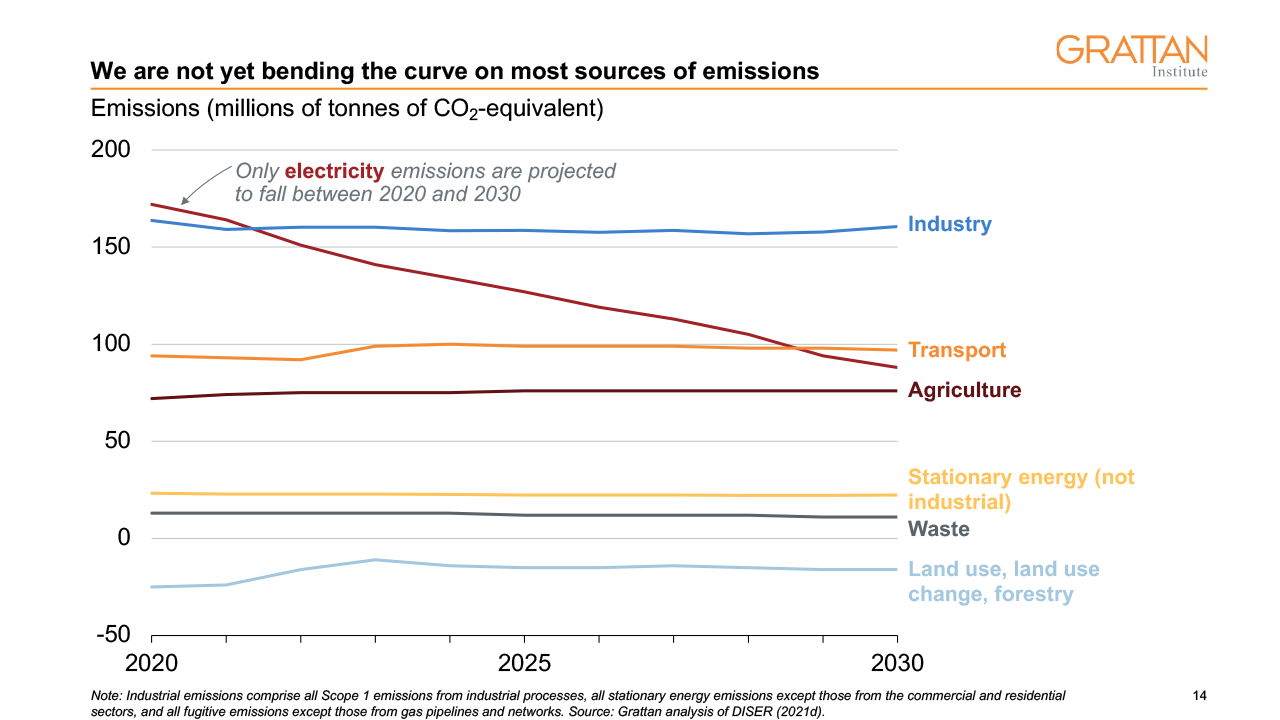

Any credible path to net zero means picking up the pace of decarbonisation in the energy sector and starting to bend the curve on emissions in industry, transport, and agriculture over this decade.

We are not yet on that path. Indeed, the latest forecasts suggest that we are yet to shift the dial beyond electricity emissions.

The scale and pace of change required have led my Grattan Institute colleagues to dub it an industrial revolution – on a deadline.[14] But if the challenge is large, so is the opportunity.

Perhaps the clearest way to think about it is a revolution with three fronts.

First, and most difficult, is supporting people affected by the decline of activities such as coal mining that are incompatible with a net-zero economy. The challenge is marrying the phase-out in a way that provides genuine opportunities for workers in the regions such as the Hunter Valley, Mackay, and Collie.

Second, there are existing activities such as steel-making and aluminium production that should be able to transform through low-emission technologies and practices.[15] The transformation of the electricity grid to support significant growth in renewables generation is a crucial part of this shift.

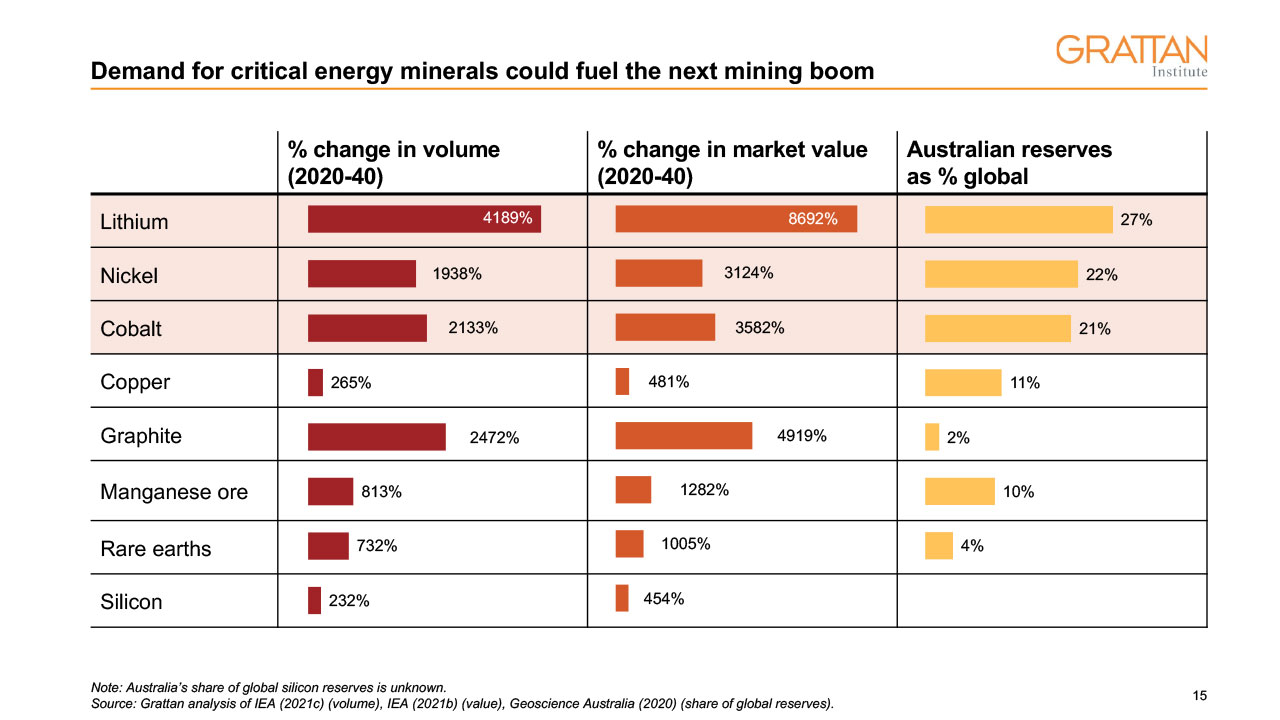

Third, there are the straight-up opportunities. New activities such as low-emissions extraction and processing of critical minerals are small today, but the potential demand is large, and Australia has significant comparative advantages, not to mention large shares of global reserves for important minerals such as lithium, nickel, and cobalt.

Crucially, if we deliver on the opportunities on the second and third fronts, these offer well-paid regional jobs in industries with a sustainable future.[16]

Once again, Australia is the lucky country – we are extraordinarily blessed with abundant supplies of renewable energies and critical minerals. I hope we can today commit to being first-rate leaders who will make the most of this luck to build future prosperity.

Theme 3: The future is digital

The third and final structural trend I want to touch on is the rise of the digital economy.

To date, digital transformation has perhaps loomed larger in our everyday lives than in economic performance, triggering macroeconomist Robert Solow’s quip that ‘we can see the computer age everywhere except in the productivity statistics’.

But there have always been lags between innovation and the economic dividends it can unleash. This is the so-called S curve effect – business simply takes a while to harness the productive capacity of new technologies.

Technologies like AI, data analytics, quantum computing, and robotics continue to develop in leaps and bounds. And bit by bit we are learning how to use them to deliver better and cheaper goods and services. This is why I find myself increasingly aligning with the techno-optimists about the transformative potential of these technologies.[17]

One reason this is so significant is that these technologies have the potential to deliver significant improvements in productivity in services sectors, where it has historically been harder to shift the dial.[18]

From touchscreen ordering in dumplings bars to AI algorithms to prioritise scarce emergency room resources, the use case for these technologies will continue to evolve.

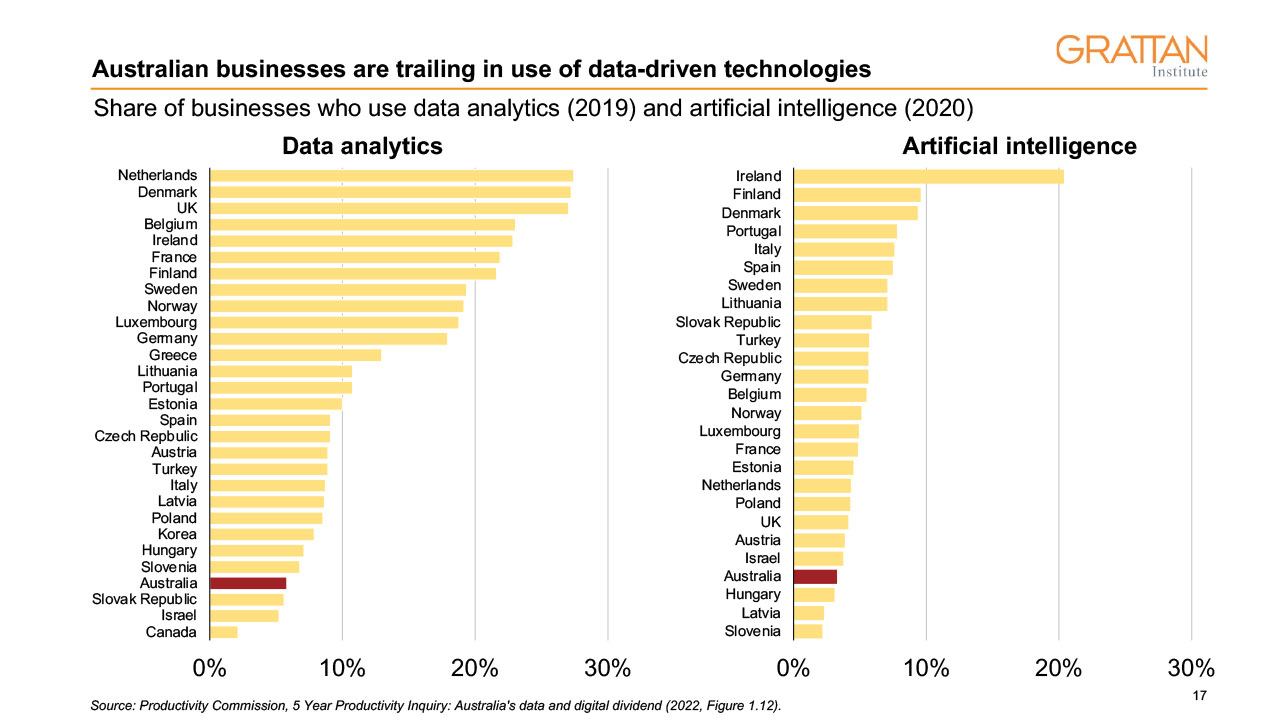

Australia does well in terms of some of the foundations – we compare positively internationally on things like cloud connectivity. But we have much lower adoption of the tools such as data analytics and artificial intelligence that will be critical in driving process improvements.

The most common barriers to technology and data adoption identified by Australian businesses are inadequate internet, lack of skills, limited awareness, and uncertainty about benefits and costs of new technologies, particularly of changing over legacy systems.[19]

Some of these require government investments such as broadband services, cybersecurity, and tech skills – but they also require Australian managers to have the know-how to recognise and respond to the opportunities ahead.

Prioritising Prosperity

So with that context, let me return to my original question: how do we ensure that Australia is best placed to flourish in coming decades given these shifts in economic activity and work?

I want to touch on 3 priorities that need to be on any future-proofing agenda and should be a central part of our discussion over the next two days.

Priority 1: Investing in human capital

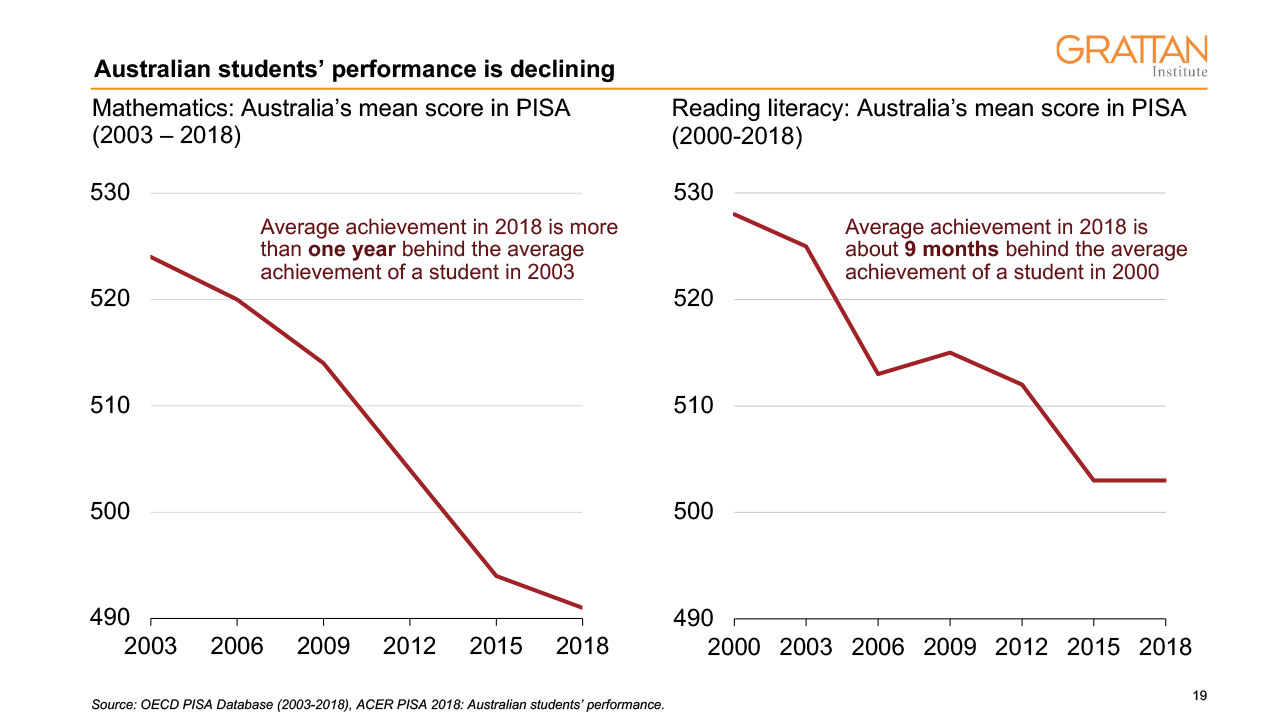

A flourishing modern economy requires investing in people. Indeed, Bill Gates has argued that the best leading indicator of a country’s outlook in 20 years’ time is the performance of its education system.[20] Unfortunately, that particular leading indicator doesn’t look too crash hot for Australia.

Data from the OECD shows that performance of Australian school students in reading and maths – both compared to other countries AND to our own performance over time – is going backwards.

The average Year 9 student is more than one year behind in maths compared to where the student of the same age was at the turn of this century. For reading it is around 9 months. Just as worrying, the learning gap between students from advantaged and disadvantaged backgrounds more than doubles between Year 3 and Year 9.[21]

If we are going to thrive as a nation and boost our prosperity, we simply must turn this around.

There is a growing evidence base around what works in terms of teaching, but we struggle more with how to flow that through to practice on the ground. At the same time, we need to do much more to attract and retain high-performing teachers.[22]

There are other aspects of education that will also need to evolve if we are going to remain a leading economy in coming decades:

- Boosting the vocational education and training system that has been left as the poor cousin to our universities;

- Improving links between industry, VET, and higher education institutions to build feedback loops on the skills that are needed as jobs evolve;

- Acknowledgement that education is a lifelong endeavour – for example, through recognition of micro-credentials and better support for on-the-job training; and

- Attracting the best and brightest to Australia by improving the composition and functioning of our migration program.

Priority 2: Making better use of our talent pool

Also critical to Australia’s success will be harnessing our existing talent pool to its fullest potential.

One US study estimates that up to 40 per cent of the growth in US living standards between 1960 and 2010 was due to better allocation of talent, as barriers to women and minorities participating in the workforce were reduced.[23] Removing barriers to participation deepens the talent pool and makes the best use of a country’s human capital.

This process still has a significant distance to run in Australia. Australia has some of the highest levels of education for women in the world, but we currently rank 38th in the world when it comes to women’s economic opportunities.[24]

Women are often excluded from full-time work, and from the most prestigious high-paid roles, because these so-called ‘greedy jobs’ are incompatible with the load of unpaid care still disproportionately shouldered by women.[25]

I can’t help but reflect that if untapped women’s workforce participation was a massive ore deposit, we would have governments lining up to give tax concessions to get it out of the ground.

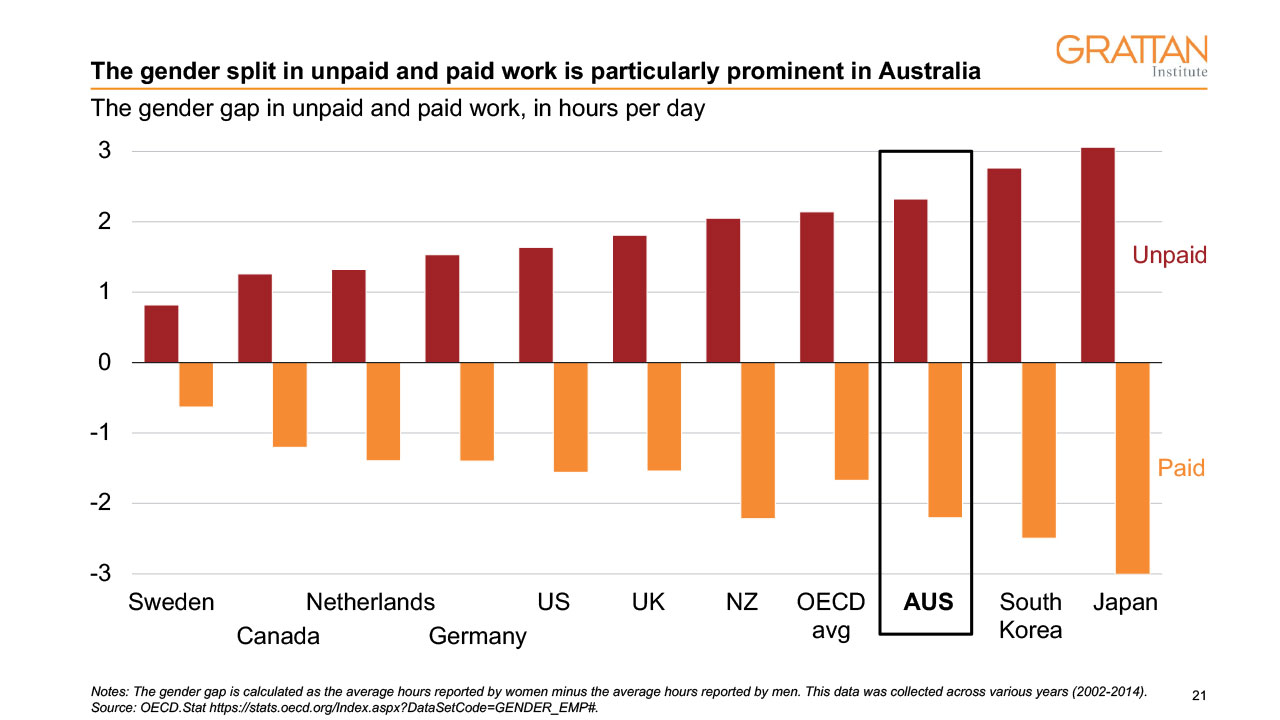

Existing policy combined with gendered norms box in women’s and men’s choices. Australia has some of the most gender-segregated occupations,[26] as well as some of the most gendered divisions of labour, in the OECD.[27]

Indeed, we lag only a few countries such as Japan and South Korea in the relatively large premium in hours of unpaid work done by women compared to men, and the mirror gender gap in paid work hours.

High-quality, low-cost early education and care is necessary to unlock participation from women who would like to work more but who are side-lined by substantial cost hurdles.[28] Given these barriers, I’m delighted by the federal government’s emphasis on making early learning and care more affordable and taking steps towards universal low-cost care. Similarly, state government moves to make kindergarten free for 3 and 4-year-olds and tackle childcare deserts are important for early education as well as women’s workforce participation.

But generational change will only come if men are also encouraged to participate more in unpaid care. Cultural shifts like this tend to play out over decades rather than years. BUT policy can shape culture.

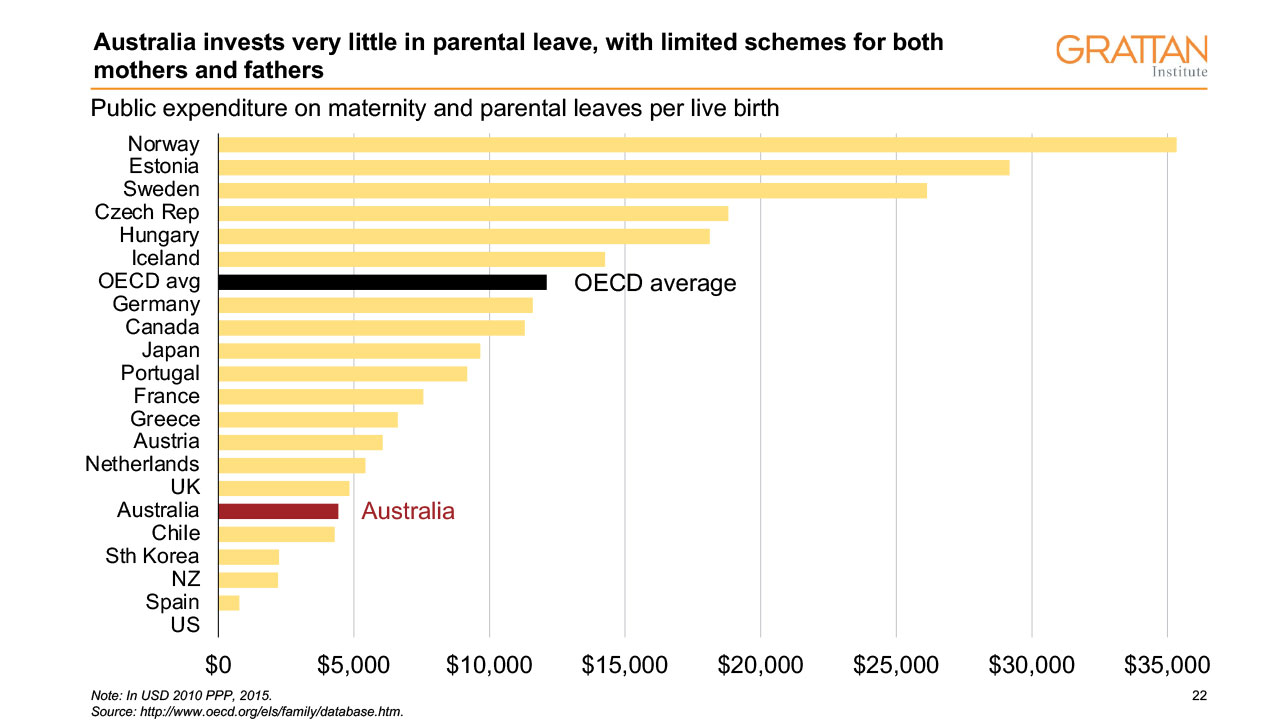

Australia invests less in paid parental leave than most other OECD nations. Yet there is growing evidence from other countries with more generous and gender-equal leave schemes that these can be an important catalyst for change.[29]

In Australia it is business that is leading the charge. But for society-shaping changes, the government paid parental leave scheme will also need to evolve.[30]

Other changes will also be needed to make sure we make the best of our talented people in the decades to come:

Tackling barriers for other groups – I’ve focussed my remarks here on women with children, but it is equally important that we tackle both the economic and structural barriers to other groups participating to their fullest, including Australians with disabilities, our First Nations people, and older Australians.

Making sure care jobs are good jobs – properly remunerating care work is going to be critical to providing the quality and quantity of health, disability, and aged care services that our older population will need.

The same is true for our early childhood workers, who are both critical enablers of workforce participation for parents, and the first and crucial step in the formal learning journey of our children.

These sectors are faced with dire shortages of workers.

In aged care, CEDA estimates an additional 30-35,000 direct care workers will be needed annually.[31] For early learning and care, the Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority estimates we will need an extra 39,000 early childhood workers by next year.[32]

This problem has been a long time in the making.

High workloads and low pay are pushing people out of these sectors and making it unattractive for others to enter.

58 per cent of early childhood workers are paid award wages, which can be as low as $22 an hour.[33] You can certainly understand why an early childhood educator might decide to step away from their important but complex and emotionally-taxing work to take up a higher-paid position at Bunnings or working the drive-through at McDonalds.

These are not just ‘normal’ IR questions – low wages in these sectors are a result of entrenched gender biases and expectations that women will care selflessly and for little money. And for a long time they have. But now, both fairness and market reality dictates that pay will need to rise.

It is critical for governments to make these investments because these sectors are the enablers – care workers, as well as delivering a crucially important service, free up others to participate in the paid workforce. And while as a society we do not baulk at billions being channelled into new roads to shave a few minutes off commute times, we have not made the necessary investments to ensure large groups of willing workers can make it to work at all.

Priority 3: Restoring economic dynamism

One of the most concerning aspects of the more recent slowdown in productivity growth has been the extent it derives from a decline in economic dynamism.

The Australian economy, like all of us, looks increasingly older, fatter, and slower.

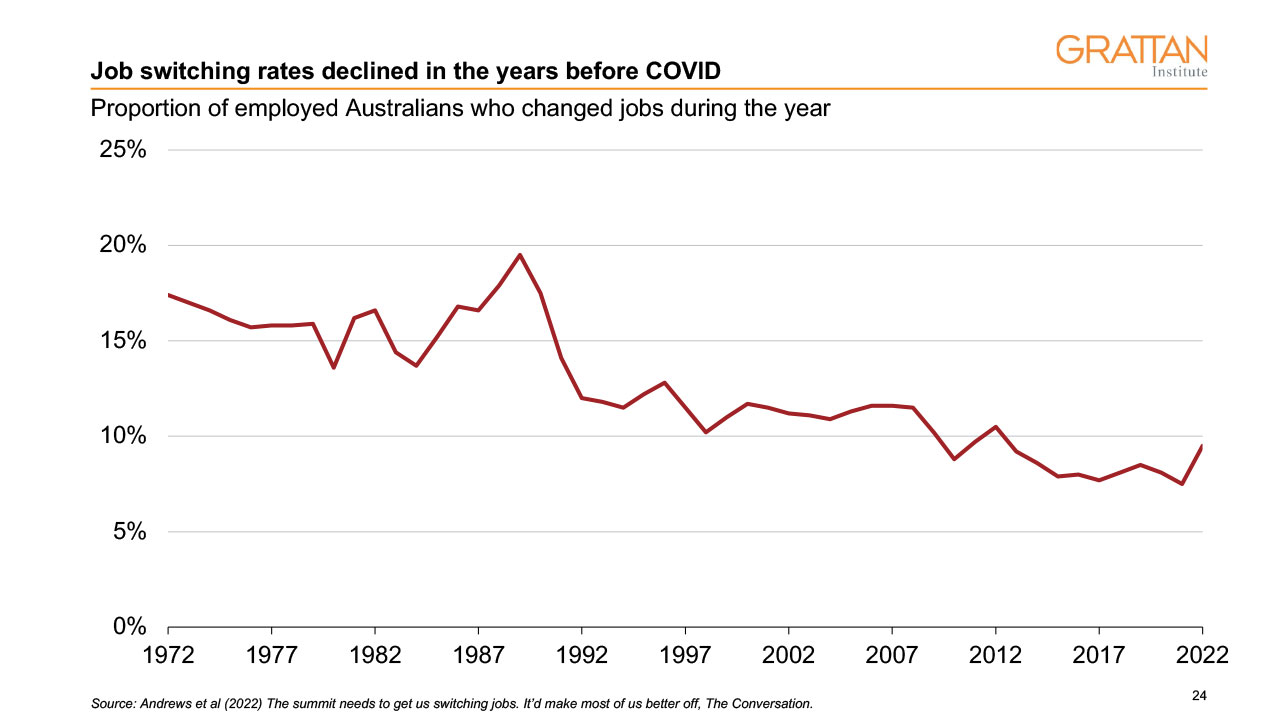

Rates of firm start-ups, exits, and job switching declined in the years before COVID, impeding the normal flow of resources from lower-productivity to higher-productivity firms.[34] Indeed, not only are we not experiencing a Great Resignation in Australia, it’s something like the opposite – the proportion of workers who change jobs each year has been declining steadily for decades.

In addition, the performance gap between firms on the global frontier of technology and Australian firms has widened.[35]

Lower levels of dynamism and innovation have been linked to a lack of competitive pressure in the economy.

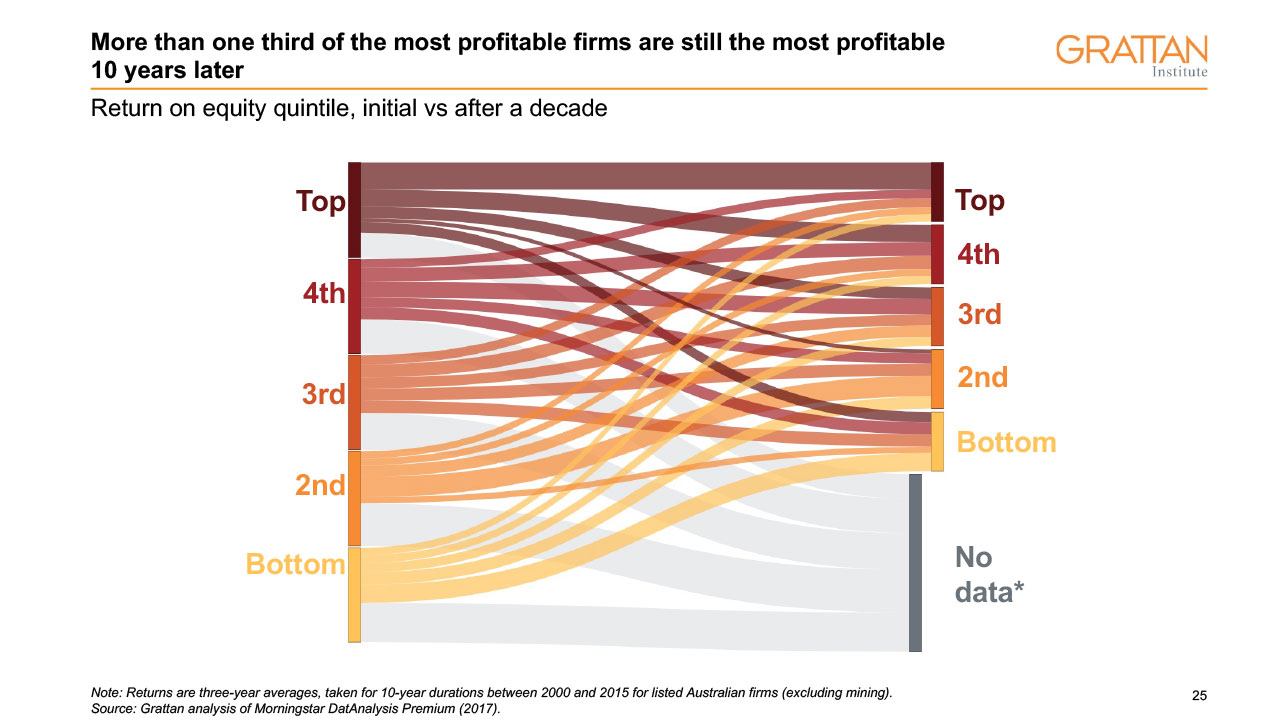

In competitive markets, excess profits should be dissipated overtime as new and innovative competitors enter. But increasingly in Australia and elsewhere we have seen the biggest and most profitable firms remain largely untroubled by new competitors.

Grattan Institute work shows that among the 20 per cent of Australia’s most profitable firms in 2015, almost one third were also among the most profitable a decade previously.[36] And recent research by Australia’s Competition Minister Andrew Leigh shows that turnover in the group of market leaders across Australian industries has slowed.[37]

While being relaxed and comfortable may be profitable,[38] it is not good for Australia’s long-term economic prospects.

So how do we restore a more dynamic business sector?

Making sure that Australia’s competition laws are fit for purpose is part of the response. Healthy competition is not just about lower prices, but the relentless quest to innovate to deliver new and better products and services.[39] The former head of the ACCC, Rod Sims, has argued that the current mergers laws are failing to adequately protect competition.[40] His warnings should prompt serious thought.

Governments should also be wary of the capacity of their own decisions to divert resources from productive investments.

Poor policy design has cost consumers and taxpayers in a whole range of sectors, from superannuation[41] to vocational education[42] to disability services[43].

Beyond the immediate waste of this cream-skimming is the dynamic costs. Economists have long warned of the productivity-sap from rent-seeking.[44] We should not want to be a country where firms see more upside in lobbying to get a better deal from policy makers than from investing in better products and services.

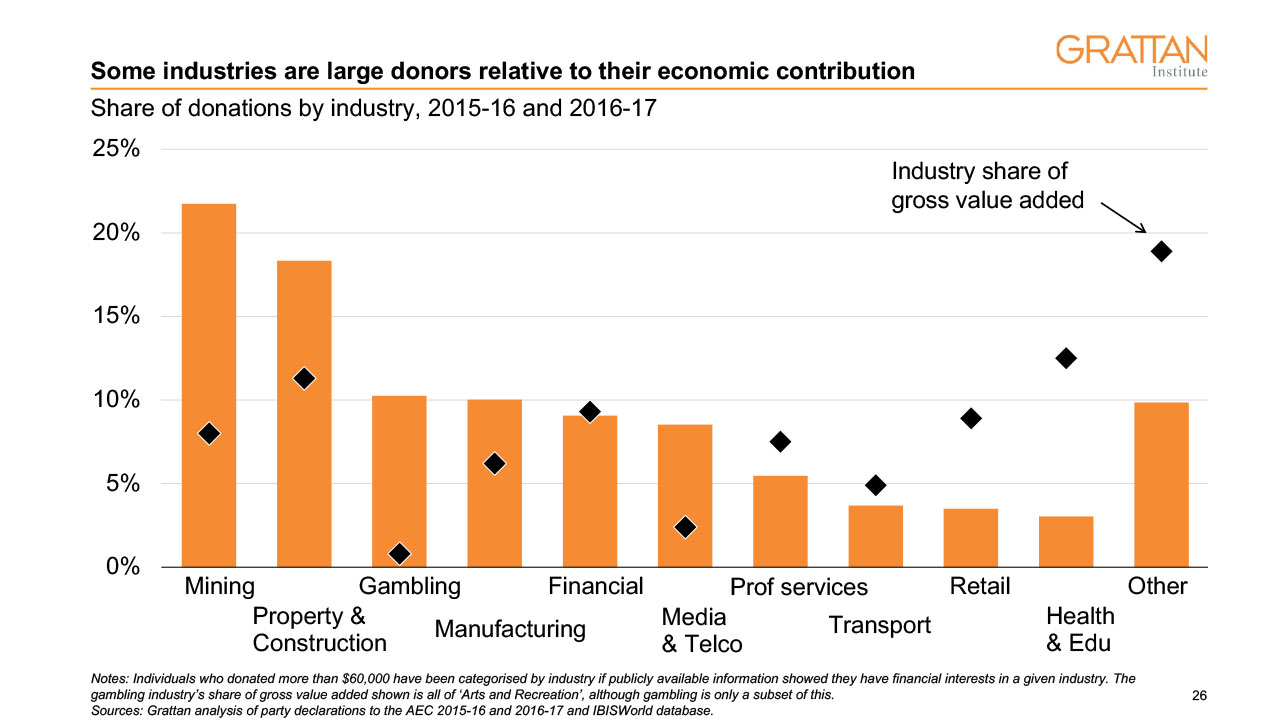

Grattan Institute’s 2018 report, Who’s in the Room, suggests this concern is real for Australia. Heavily regulated sectors such as mining, property and construction, and gambling are characterised by remarkably high levels of political donations and lobbying compared to their relative economic contribution.[45]

That is why institutional reforms to reduce disproportionate access and influence are economic reforms as well as integrity reforms.

It is also why market design and commissioning in government-funded markets such as care services, education and training, and health represent new frontiers for the government’s microeconomic reform agenda.[46]

Restoring economic dynamism will also require an appetite to tackle other impediments to the movement of labour and resources. These include overly-restrictive land-use planning laws and stamp duties that discourage mobility and sap the productive capacity of our cities.[47]

Addressing out-dated skilled migration rules should also be high on the list. Overly bureaucratic skills lists are poor predictors of the future economic contribution of new migrants. Targeting higher-wage migrants directly for both temporary and permanent skilled migration would improve the productivity of the migration system and the Australian workforce.[48]

But finally – what of our people? How do we encourage workers to be bold and thrive in a more dynamic economy of the future?

The 2018 international PISA survey found that 42 per cent of Australian teenage boys and 52 per cent of teenage girls expect to work in one of just 10 common jobs by the age of 30, including as a lawyer, doctor, or police officer.[49] This set of aspirations has actually narrowed since the turn of the century.

The lack of awareness of the breadth of jobs, particularly in fast-growing sectors, diverts young people from career paths that would generate greater benefits for both them and the country.

We need much more communication with parents and young people about the jobs and skill sets of the future.

We also need to tackle structural impediments to dynamism and risk taking.

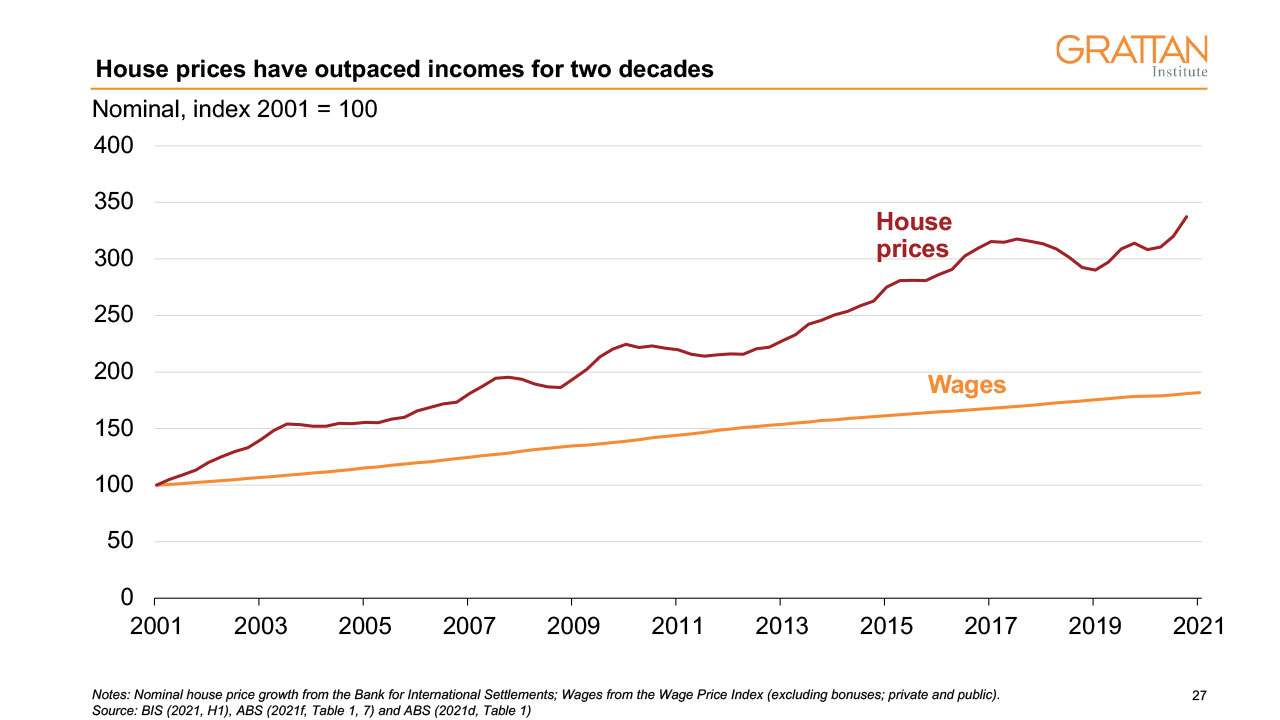

The two-decades-long run up of house prices relative to incomes means that any young person hoping to get on the property ladder can expect to take on vastly more debt than a young homebuyer 20 years ago. High household indebtedness constrains the capacity of young people to take on the risk of starting a business or even considering a mid-life career change.

Similarly, if we want to genuinely improve worker mobility, we have to consider the role of the social safety net. Upgrading skills or even changing jobs can be costly and risky, particularly for more vulnerable workers.

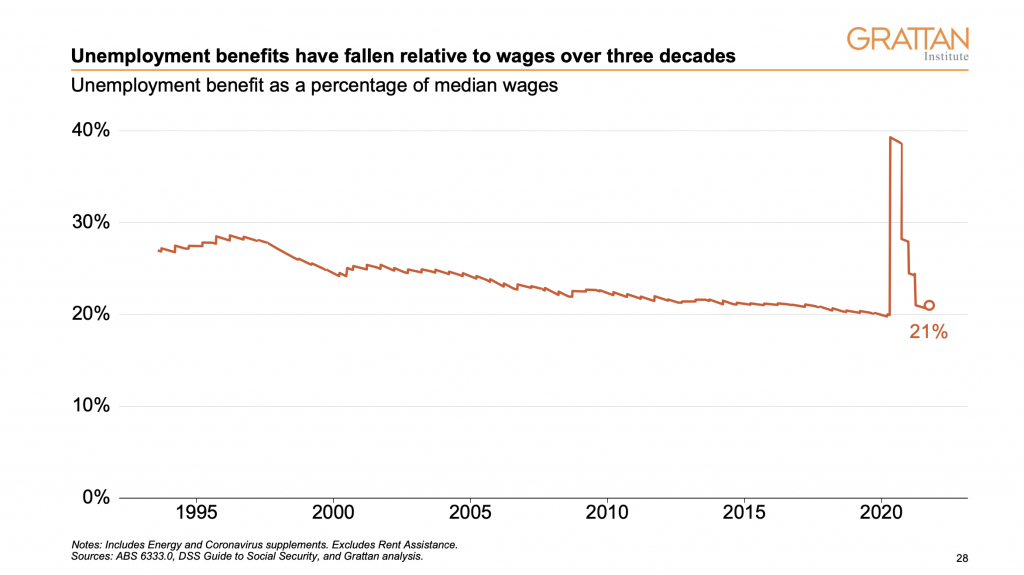

The weakening of the safety net, as unemployment benefits have declined relative to wages, means that workers are less well insured for taking these risks. [50]

If we want Australians to take a leap in the name of better opportunities, they need to know society will support them if they fall.

In conclusion, let me say that this summit comes at an extraordinary time.

Unemployment is lower than I’ve experienced in my lifetime, and we are in the early phase of significant structural shifts in jobs and activity as our economy decarbonises and digitises.

This is a summit for grappling with how we manage those transitions and embrace the challenge of creating a more productive and dynamic future.

So my final provocations to delegates are these:

- Can we commit to lock in full employment as a policy objective, and capitalise on the extraordinary opportunity to give our long-term unemployed, older job seekers, and people with a disability a chance to open the door to participation in paid work?

- Can we decide to invest in human capital big time – to turn around the slide in our school results, rebuild our vocational education and training sector, and improve the quality of the signals we send to our young people about the skills and qualifications that will be needed in future?

- Can we embrace the principle that no one who wants a job or more hours should be held back by structural barriers, such as expensive or inaccessible care?

- And can we recognise the importance of boosting innovation, of strong market competition, of better policy design, and of government investments in enablers like cyber security, to restore our economic dynamism and even become an economy on the technological frontier?

Thank you all – and I look forward to productive discussions over the next two days.

Footnotes

- ABS Labour Force, Australia, July 2022.

- Coates, B. and A. Ballantyne (2022). No one left behind: Why Australia should lock in full employment. Grattan Institute.

- Coates, B. and A. Ballantyne (2022). No one left behind: Why Australia should lock in full employment. Grattan Institute.

- Coates, B. and A. Ballantyne (2022). No one left behind: Why Australia should lock in full employment. Grattan Institute.

- Coates, B. and Ballantyne, A. (2022). No one left behind: Why Australia should lock in full employment. Grattan Institute; Da Silva, L. et al (2022). Inequality hysteresis and the effectiveness of macroeconomic stabilisation policies. Bank for International Settlements.

- ABS Business Indicators, Australia, March 2022.

- Productivity Commission (2022). 5-year Productivity Inquiry: The Key to Prosperity, Interim report 1, pp. 2-3.

- Adams et al (2022) highlight that the share of productivity gains that are passed through to workers has declined by 25 per cent over the past 15 years, with the largest declines in retail trade, accommodation, and food services. Adams, N. et al (2022). Better harnessing Australia’s talent: five facts for the Summit, e61 Institute.

- Productivity Commission (2022). 5-year Productivity Inquiry: The Key to Prosperity, Interim report 1, p.30.

- Between 1970 and 2020, Australia’s labour productivity ranking fell 10 places, from sixth in the OECD to 16th. Productivity Commission (2022). 5-year Productivity Inquiry: The Key to Prosperity, Interim report 1, p. 31.

- ABS Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, Table 4.

- ABS National Accounts, Industry Gross Value Added, Table 37.

- Share of gross value added, excluding ownership of dwellings. ABS National Accounts, Industry Gross Value Added, Table 37.

- Wood, T. Reeve, A. and E. Suckling (2022). The next industrial revolution: Transforming Australia to flourish in a net-zero world. Grattan Institute.

- Wood, T. Dundas, G. and J. Ha (2022). Start with steel: A practical plan to support carbon workers and cut emissions. Grattan Institute.

- Wood, T. Reeve, A. and E. Suckling (2022). The next industrial revolution: Transforming Australia to flourish in a net-zero world. Grattan Institute.

- Baily, M., Manyika, J.M., and S. Gupta (2013). U.S. Productivity Growth: An Optimistic Perspective. International Productivity Monitor. Vol 25. 3-12; Mokyr, Joel (2014) Secular Stagnation? Not in Your Life, in Coen Teulings and Richard Baldwin (eds.), Secular Stagnation: Facts, Causes, and Cures. London: CEPR Press; Saniee, I., Kamat, S., Prakash, S. and M. Weldon (2017) Will productivity growth return in the new digital era? Bell Labs Technical Journal, Vol. 22, 1–18. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7951155; Nordhaus, W. (2015) Are we approaching an economic singularity? Information technology and the future of economic growth. NBER Working Paper, No. 21547. Cambridge, MA. September. https://www.nber.org/papers/w21547.pdf.

- Productivity Commission (2022). 5 Year Productivity Inquiry: Australia’s data and digital dividend, Interim report 2.

- Productivity Commission (2022). 5 Year Productivity Inquiry: Australia’s data and digital dividend, Interim report 2.

- Kamenetz, A. (2013). Bill Gates on education: We can make massive strides. Fast Company.

- Hunter, J. and O. Emslie (2021). Three things we should do to close the education equity gap. The Age.

- Goss, P. and J. Sonnemann (2019). Attracting high achievers to teaching. Grattan Institute.

- Hsieh, C., Hurst, E., Jones, C.I., and P.J. Klenow (2019). The allocation of talent and US economic growth. Econometrica, Vol. 87, No. 5, 1439–1474.

- World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Report, 2022. Similarly, according to OECD data Australia ranks 4th for tertiary education attainment for women but 31st for full-time work. See: OECD.Stat, latest data for educational attainment (tertiary qualification) and full-time and part-time employment by gender.

- Claudia Goldin (2021). Career and Family: Women’s Century-Long Journey Toward Equity, Princeton University Press.

- Finance and Public Administration References Committee (2017). Gender segregation in the workplace and its impact on women’s economic equality; OECD.Stat ‘distribution of employment by aggregate sectors, by sex’.

- OECD.Stat: latest data for ‘time spent in paid and unpaid work, by sex’.

- Wood, D., Griffiths, K., and O. Emslie (2020). Cheaper childcare: A practical plan to boost female workforce participation. Grattan Institute.

- Wood, D., Emslie, O., and K. Griffiths (2021). Dad days: How more gender-equal parental leave would improve the lives of Australian families. Grattan Institute.

- Wood, D., Emslie, O., and K. Griffiths (2021). Dad days: How more gender-equal parental leave would improve the lives of Australian families. Grattan Institute.

- CEDA (2022). Duty of Care: Aged Care Sector in Crisis.

- ACECQA (2019). Progressing a national approach to the children’s education and care workforce.

- 2021 Early Childhood Education and Care National Workforce Census report; Fair Work Ombudsman.

- Hambur, J. (2021). Product Market Power and its Implications for the Australian Economy, Treasury Working Paper; Andrews, D. and D. Hansell (2019). Productivity‑Enhancing Labour Reallocation in Australia, Treasury Working Paper.

- Analysis focuses on non-resource and non-financial sector firms. Andrews, D., Hambur, J., Hansell D., and A. Wheeler. (2022). Reaching for the stars: Australian Firms and the Global Productivity Frontier, Treasury Working Paper.

- Based on return on equity quintiles. Minifie, J. (2017). Competition in Australia: Too little of a good thing? Grattan Institute.

- Leigh, A. (2022). A more dynamic economy. FH Gruen Lecture, Australian National University, Canberra, 25 August 2022.

- Hambur, J. (2021). Product Market Power and its Implications for the Australian Economy, Treasury Working Paper.

- For example, market competition has been shown to be an important factor in driving technology adoption – see for example, Andrews, D., Nicoletti, G. and C. Timiliotis (2018) Digital technology diffusion: A matter of capabilities, incentives or both?, OECD Economics Department Working Papers 1476. Andrews et al (2022) also finds that declining competitive pressures are one of the main reasons Australian firms have become slower to adopt, innovate, and improve their productivity performance.

- Sims, R. Protecting and promoting competition in Australia. Competition and Consumer Workshop 2021 – Law Council of Australia, 27 August 2021; Sims, R. Some reflections of a former competition agency head. CPI Antitrust Chronicle August 2022.

- Productivity Commission (2019). Superannuation Inquiry.

- Education and Employment References Committee (2015). The operation, regulation and funding of private vocational education and training (VET) providers in Australia.

- Per Capita (2022). Contracting Care: The rise and risks of digital contractor work in the NDIS.

- Murphy, K.M., Shleifer, A., and R.W. Vishny (1993). Why Is Rent-Seeking So Costly to Growth? The American Economic Review, 83, 2, pp. 409-414; Acemoglu, D. and J.A. Robinson, (2019). Rents and economic development: the perspective of Why Nations Fail. Public Choice 181, 1/2, pp.13–28.

- Wood, D. and K. Griffiths. (2018). Who’s in the room? Access and influence in Australian politics. Grattan Institute.

- Productivity Commission (2017) Shifting the Dial: 5 year productivity review; Wood, D. et al. (2022) Orange Book 2022: Policy priorities for the federal government, Grattan Institute; NSW Productivity Commission (2020), Productivity Commission Green Paper: Continuing the Productivity Conversation.

- Wood, D. et al. (2022) Orange Book 2022: Policy priorities for the federal government, Grattan Institute.

- Permanent employer sponsorship should be opened up to workers in any occupation provided they are paid at least $85,000 a year – median full-time earnings in Australia. The minimum salary threshold for sponsoring temporary skilled migrants should rise to $70,000, while allowing employers to hire temporary skilled migrants into jobs in any occupation, provided they are paid the same as equivalent Australians doing similar jobs. See Coates, B. and T. Reysenbach (2022). Making skilled migration better, not just bigger, should be the priority at the Jobs Summit. Grattan Blog Post.

- Based on the 2018 PISA survey and detailed in OECD (2018), Dream Jobs? Teenagers’ Career Aspirations and the Future of Work, p. 18.

- See also discussion: Adams, N. et al (2022). Better harnessing Australia’s talent: five facts for the Summit, e61 Institute.

While you’re here…

Grattan Institute is an independent not-for-profit think tank. We don’t take money from political parties or vested interests. Yet we believe in free access to information. All our research is available online, so that more people can benefit from our work.

Which is why we rely on donations from readers like you, so that we can continue our nation-changing research without fear or favour. Your support enables Grattan to improve the lives of all Australians.

Donate now.

Danielle Wood – CEO