Think big for a better personal income tax system

by Aruna Sathanapally, Jessica Geraghty

The question at the heart of last week’s economic reform roundtable was, how can we lift Australia’s productivity and Australians’ prosperity?

One of the most powerful levers the federal government holds to achieve this is tax policy. Improving the efficiency of the tax system, by shifting Australia’s tax mix from more-costly to less-costly taxes, could materially boost Australians’ living standards.

And in the longer term, revenue will need to grow to manage the budgetary costs of an ageing population and rising community expectations of government services, especially if economic growth remains lower for longer.

Australia’s tax system offers many opportunities for reform. But the best place to start is where we have the greatest expert agreement on the problems, and clarity about solutions: rebalancing the personal income tax system.

Think big: think personal income tax

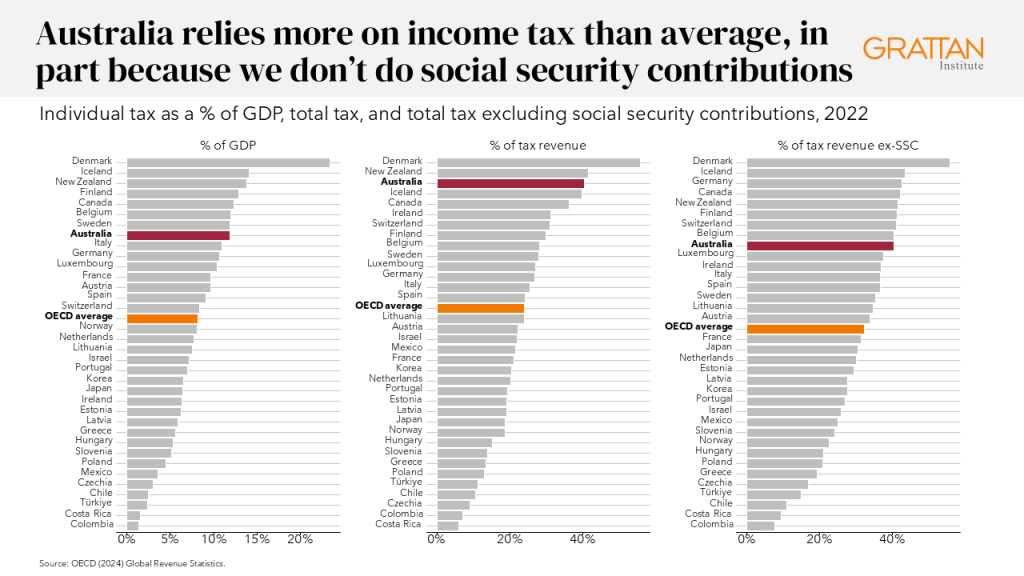

Personal income tax is by far the largest component of Australia’s tax revenue. It makes up 52 per cent of the federal government’s tax take, nearly double what the government receives in company tax.

Australia relies more than our OECD peers on income tax, although the disparity gets smaller when we take into account social security contributions – taxes on employment that most OECD countries use to pay for unemployment benefits and pensions, but which Australia doesn’t have.

The current system is unfair and unsustainable

The issue with the current system is the imbalanced way in which we collect tax.

Our personal tax system is ‘leaky’: We lean most heavily on taxes on wages and salaries, and at the same time, have created very generous tax breaks for other types of income.

This inequity is driven by several factors:

- The treatment of housing investment, with particularly generous concessions for capital gains and rental deductions;

- The use of trusts and private companies to manipulate taxable income; and

- The treatment of income in retirement, where superannuation earnings are tax-free for retirees.

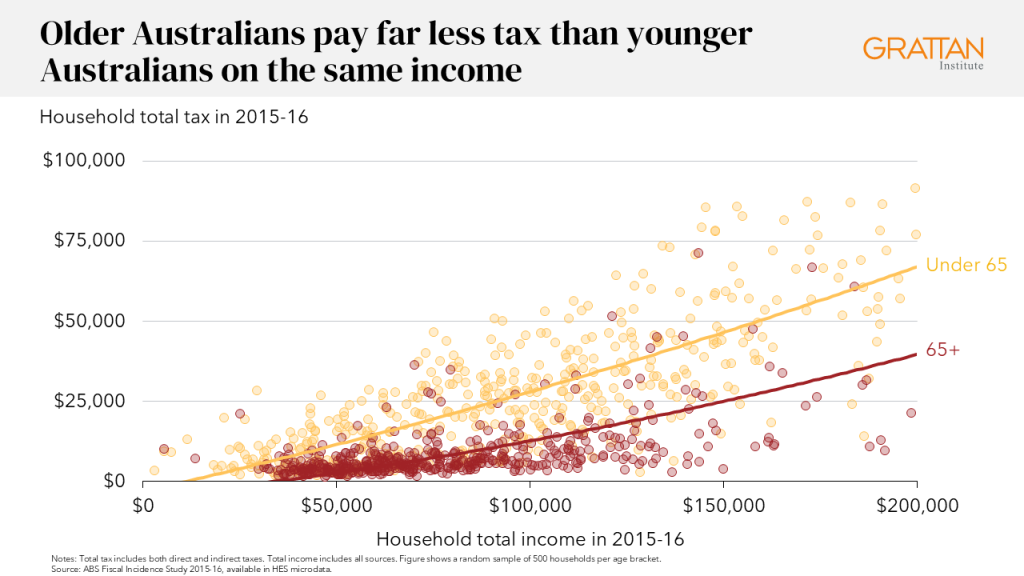

The result is that Australia’s tax system treats households on the same income vastly differently – so it does pretty poorly on horizontal equity.

In practice, this means that a retiree household earning $100,000 per year pays less than half of the tax of a working household with the same income, purely because of their age.

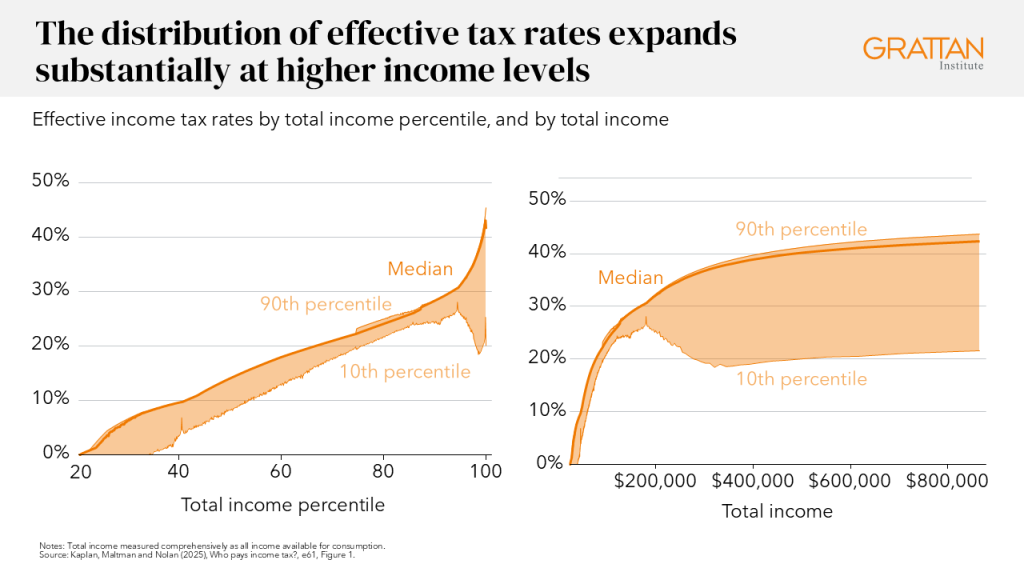

And at the top end of the income distribution, the system does poorly on vertical equity, or the principle that those who have the resources to contribute proportionally more, should.

Recent analysis by e61 shows that among the top 5 per cent, the amount of tax paid varies hugely. Indeed, some of the highest earners have lower tax rates than people on incomes only one-fifth as big.

There is more equity among the other 95 per cent, but this only captures households that file a tax return. Importantly, this excludes many older households.

These problems, well-known to most policymakers, add up to a system replete with perverse incentives and unprincipled outcomes.

We know what we need to do

Given the stark nature of these problems, you might be forgiven for thinking that the path to improve our personal income tax system is murky and unclear.

But we know how to fix it. The solutions are legislative, and the power sits with the federal government. The problem has always been political: the noise that attends any suggestion that tax breaks be withdrawn.

The system can be fixed in pieces: reducing superannuation concessions so the super system meets the policy objective of saving for a decent retirement, rather than being a tax shelter; introducing at least a low tax rate on earnings in retirement; reducing the capital gains tax discount; reforms to family trusts. We calculate that these reforms could raise $20 billion a year.

Or the repair could be systematic: a dual-income system that brings consistency to how we treat different types of savings.

Tackling the treatment of income from wealth would help address the inequities in the system and give us better options for the future. It would mean that total income tax can keep pace with our changing needs and expectations, without increasing the burden on a working-age population that is getting smaller as the population gets older.

The government has announced that reforming Australia’s “imperfect” tax system is one of its longer-term priorities, to deliver on “our responsibilities to the coming generations”.

So, tax reform is finally on the agenda. But Australia must not be complacent about this opportunity. We have the chance to think bigger than overnight winners and losers, and beyond the short term. And we should remember that the best reform is not the one most perfectly designed: it’s the one that actually happens.