On Tuesday, the Federal Government announced its Plan for achieving net zero by 2050. But there are two key problems with the plan. The first: it contains no new policies to credibly deliver the goal.

The second? Net zero by 2050 is not sufficient to meet Australia’s fair share of keeping global warming well-below 2ºC, let alone 1.5ºC. These are the temperature goals to which Australia is committed under the 2015 Paris Agreement.

The global goal

Achieving global net-zero emissions by about 2050 is necessary but not sufficient to have a decent chance of limiting global warming to 1.5º C. And it matters how the world – and Australia – gets to net zero.

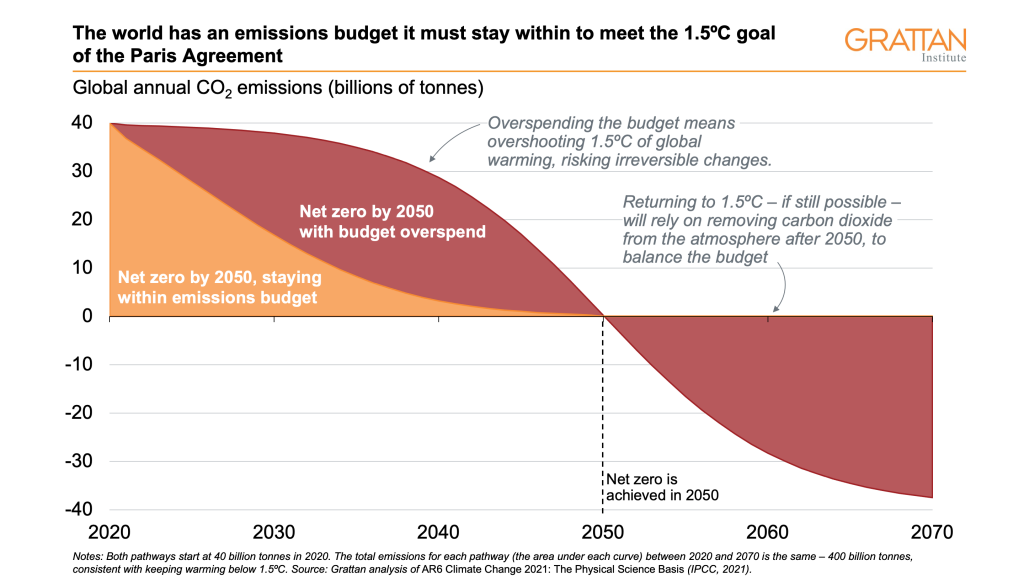

As they are emitted, greenhouse gases accumulate in the atmosphere. That means cumulative emissions over time is the key factor to mitigate climate change.1 These cumulative emissions are in effect a ‘carbon budget’ – a limit that emissions must stay within. To have a two-thirds chance of keeping warming at 1.5ºC, the world has a remaining carbon budget of about 400 billion tonnes of CO2 emissions from 2020.

Staying within that budget is the real objective. Annual global CO2 emissions averaged about 40 billion tonnes over the past decade, implying just 10 years of budget remaining at current rates before 1.5º C could well be breached.

Inherent in the concept of net-zero emissions is a strategic balance – more aggressive emissions reductions sooner mean lower absolute emissions; more conservative reductions mean higher absolute emissions and a greater risk of triggering irreversible climate change. Once the emissions budget is gone, our only option for getting global warming back below 1.5º C is to deliberately remove more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than is emitted each year, as illustrated in the chart below.

Setting emissions targets means setting a carbon budget

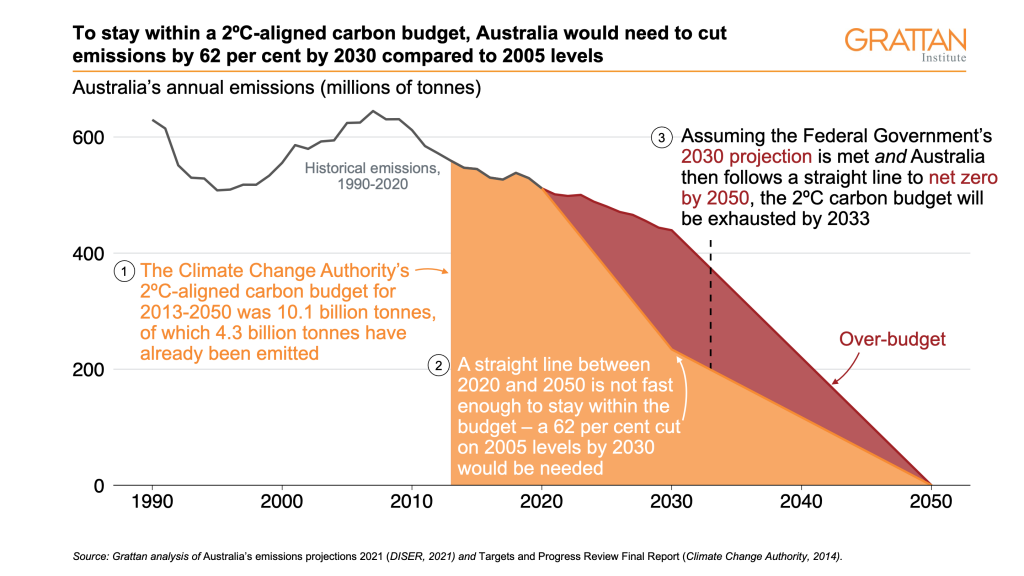

Although it is common to refer to an emissions target at a point in time (such as 2030 or 2050), the real target for a country, or indeed the world, is limiting cumulative emissions to stay within the carbon budget. For example, at the Paris COP21 in 2015, the Australian Government committed to its current Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) of reducing emissions by 26-to-28 per cent against 2005 levels. Australia’s 2030 target therefore implies limiting cumulative emissions between 2021 and 2030 to 4.8-to-4.9 billion tonnes.2

The Morrison Government’s commitment to net zero by 2050 would, if based on a 2030 outcome in line with the INDC and a straight line to net zero, mean cumulative emissions between 2021 and 2050 of 9.3 billion tonnes.

As with the global total of INDCs, Australia’s 2030 target has been widely criticised as inadequate against the goal to limit global warming to 2ºC, let alone 1.5ºC. The 2014 and last comprehensive review by the Climate Change Authority estimated Australia’s fair share of 2ºC-compatible global carbon budget would be 10.1 billion tonnes between 2013 and 2050. Australia has already consumed 42 per cent of this budget between 2013 and 2020, leaving only 5.8 billion tonnes to cover the period 2021-2050.

That means, unless it sets a more ambitious 2030 target, that Australia is planning to overshoot by more than 50 per cent the budget consistent with a warming limit of 2ºC.

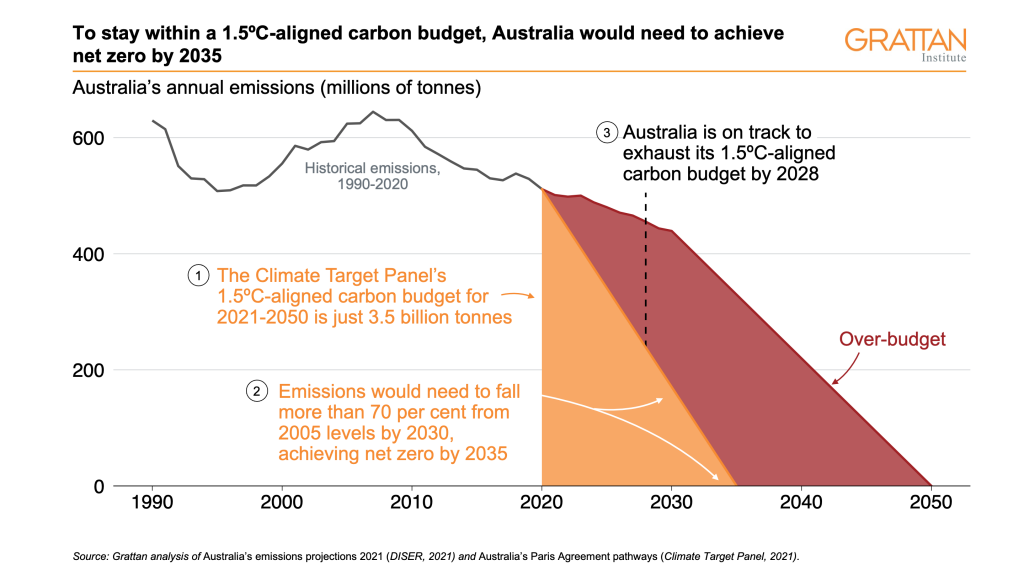

The arithmetic is even starker for achieving 1.5ºC.

Australia already emits 1.3 per cent of global emissions each year, despite having just 0.3 per cent of global population. That makes us one of the world’s biggest emitters on a per capita basis, emitting four times more than the global average. Continuing to use 1.3 per cent of the carbon budget is widely regarded as unfair, especially given that Australia is a rich, developed country.

Yet current national climate targets mean Australia is planning to take 2.3 per cent of the remaining 1.5ºC global carbon budget – in effect, carving up the carbon budget even less equally than already happens today. The consequence: either other countries must do more than their fair share to cut emissions and compensate for Australia’s excess, or the world sails past 1.5ºC. That would mean relying on net emissions eventually falling below zero – sucking more carbon out of the atmosphere than is emitted each year – to bring temperatures back down to safe limits. But it is entirely unclear who would be prepared to pay for that expensive clean-up bill.

Whether governments set a more ambitious target in line with the Paris Agreement or stick with the national target of net zero by 2050, emissions in Australia are not on track to achieve either goal. On Sunday night, Grattan Institute will publish the fifth and final report in its Towards net zero series, to give governments a practical plan that can get Australia on track towards net zero by 2050.

Footnotes

- This is particularly the case for long-lived greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, but it lasts only about a decade in the atmosphere – its impact on warming is largely determined by the rate at which humans are causing methane to be emitted compared to the rate at which existing atmospheric methane breaks down.

- The Government’s most recent projections indicate that it expects Australia will emit 4.7 billion tonnes over 2021-2030, therefore meeting our 26-to-28 per cent target.

All blog posts published by the Grattan Institute are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. You may republish our blog posts within the following guidelines.

While you’re here…

Grattan Institute is an independent not-for-profit think tank. We don’t take money from political parties or vested interests. Yet we believe in free access to information. All our research is available online, so that more people can benefit from our work.

Which is why we rely on donations from readers like you, so that we can continue our nation-changing research without fear or favour. Your support enables Grattan to improve the lives of all Australians.

Donate now.

Danielle Wood – CEO