Published at The Conversation, Wednesday 4 May

There are three critical tests for this year’s budget. Is it serious about repairing Australia’s ongoing structural budget deficits? Does it make much of a difference to economic growth? And is it fair?

Budget repair

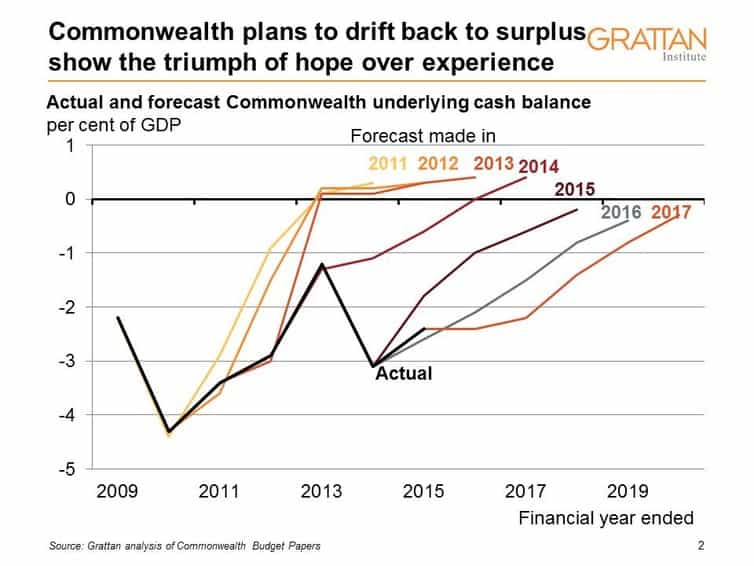

Over the last year, the bottom line got worse. The long-promised return to surplus receded another year over the horizon. This is the seventh time a budget has forecast a drift back to surplus over the following four years while the outcome for the current year showed minimal improvement over the year before.

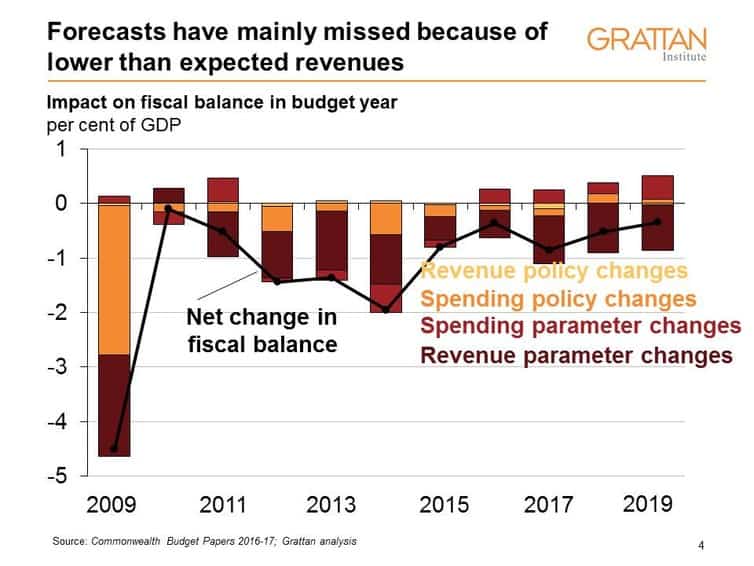

Also consistent with the history of the last seven years, most of the damage was done by “parameter variations” – changes in the economy that meant the budget didn’t live up to previous expectations.

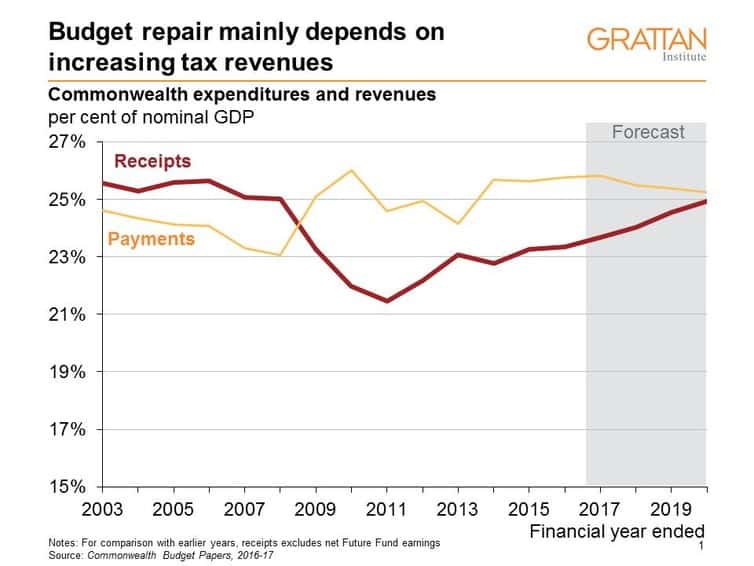

The government has made much of the need to repair the budget through spending reductions rather than tax increases. Overall, however, forecasts assume that most of budget repair will be the result of increasing revenues as a share of GDP. A large component is that nominal wages are expected to rise, leading to higher income tax collections, known by budget nerds as “fiscal drag”, and commonly referred to as “bracket creep”.

There’s plenty of room for things to keep going wrong. The largest risk is that nominal wages may be lower than forecast.

Last week the Australian Bureau of Statistics reported much lower inflation than expected. On the day of the federal budget the Reserve Bank responded by cutting interest rates, implying a real risk that unusually low inflation will persist. If it does, then income tax collections will be hit, hurting the budget bottom line, particularly in the last year or two of the budget estimates.

This presents an interesting challenge for Treasury. If an election is called towards the end of this week, then it must release PEFO – the Pre-election Economic and Fiscal Outlook – by around May 20. With inflation lurching south, PEFO may significantly revise the budget bottom line, which will inevitably raise perceptions – probably unfairly – that the government is not firmly in control of economic management.

The other big risk is that export prices fall short of forecasts. The budget assumes an iron ore price of US$55 per tonne. This is close to recent prices, but they were US$40 a tonne just six months ago. If the price drops back US$10 to US$45 per tonne, budget balances are expected to be A$4 billion a year worse off.

Specific measures don’t do much collectively to improve the budget bottom line. As with each of the last seven years, there are substantial gross tax increases and spending reductions, but other decisions largely offset these. Overall, specific measures drag on the budget outcome by $5 billion for the coming year, but improve the last estimated year (2019-20) by $6 billion.

Jobs and growth

The key selling point for the budget is “jobs and growth”. However, there are questions about whether the budget initiatives will matter much to the economy within the next four years.

The largest single initiative is a cut to the corporate tax rate, particularly for small-to-medium businesses. The tax rate will be cut from 28.5% to 27.5%, and by 2019-20 this will apply to businesses with up to $10 million in turnover, up from the current limit of $2 million.

This will doubtless be popular with hundreds of thousands of small businesses. However, given Australia’s dividend imputation scheme, the tax change makes no difference to the amount of tax levied on profits paid out to Australian business owners. A lower tax rate only matters to the budget and the economy when businesses re-invest retained earnings.

However, the overall effect will be small. The tax changes are supposed to reduce tax collected in 2019-20 by A$2 billion – by definition, money retained in businesses and re-invested. This compares with total corporate investment in capital of about A$120 billion a year, and much more in paying for additional staff. The tax change is small beer in comparison.

There may be a larger tankard of beer in reducing tax rates for foreign corporates. But they will receive no benefit until after 2020-21 – well after the next two elections. And recent work has cast doubt on how much of the economic benefit will ultimately benefit Australians.

It is stretching things to believe that other measures will turbo-charge the economy. The budget contains relatively little new infrastructure spending.

Instead there are a lot of plans to do more planning. The most promising economic feature may be a new Youth Jobs PaTH package. This replaces work for the dole with a training, internship and subsidised employment pathway that is at least a little closer to what the literature recognises as best practice.

Fairness

Despite its jobs and growth packaging, the boldest moves in the budget were about fairness. Wide-ranging reforms to superannuation are a big move in the right direction. The current system is poorly targeted, with most of the tax concessions going to the top 20% of taxpayers who need the least help in saving for retirement.

Under the reforms, the top 4% will pay about A$2.6 billion more tax in 2019-20, offset by an additional A$1.8 billion tax concessions for the bottom 28%. These are material changes very different from the tinkering at the edges that has characterised superannuation reform over the last decade.

More controversially, the budget raises the 37% income tax threshold from $80,000 to $87,000. This gives the top 20% of income earners an extra $315 a year.

The fairness of concentrating tax relief on this group depends on the date of comparison. Genuinely middle-income earners (on $45,000 a year) have lost a greater percentage of their income in tax because of bracket creep since the Coalition took office. However, the change in percentage of income paid in tax is more or less the same for all income groups since 2011-12, because lower-income groups received more benefit from carbon tax compensation.

Conclusion

Budget 2016 was much like many of its predecessors over the last seven years. Budget repair was put off till later, and the net impact of budget decisions was small.

Although much was made of individual initiatives, these are unlikely to make much difference to economic growth in the next four years.

Although fairness, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder, this budget will be easier to defend than some others in recent times.

![]()