Victoria’s energy challenge explained in 7 charts

by Tony Wood

Victoria has an unusual energy history in two key areas that are important as we contemplate a net zero future.

Firstly, for much of the past 50 years, Victoria’s economy has been powered by vast and low-cost oil, gas and cheap brown coal. But that base is rapidly disappearing. Coal power stations must close because of climate change. Local gas supplies will run short of demand within the coming years.

The dual challenges of getting off coal and gas mean that Victoria faces a harder transition to a low-emissions future than other states do.

Second, financial necessity at the beginning of this century and a period of policy leadership meant that Victoria led the country in the adoption of competition policy and energy market reform.

Unfortunately, state governments can only sell off their assets and establish private markets once. The state’s reform zeal dimmed long ago, and Victoria now needs new options.

A clear-eyed view of this history can help Victoria rise to the current and emerging challenges.

Here are the charts that explain how this came about.

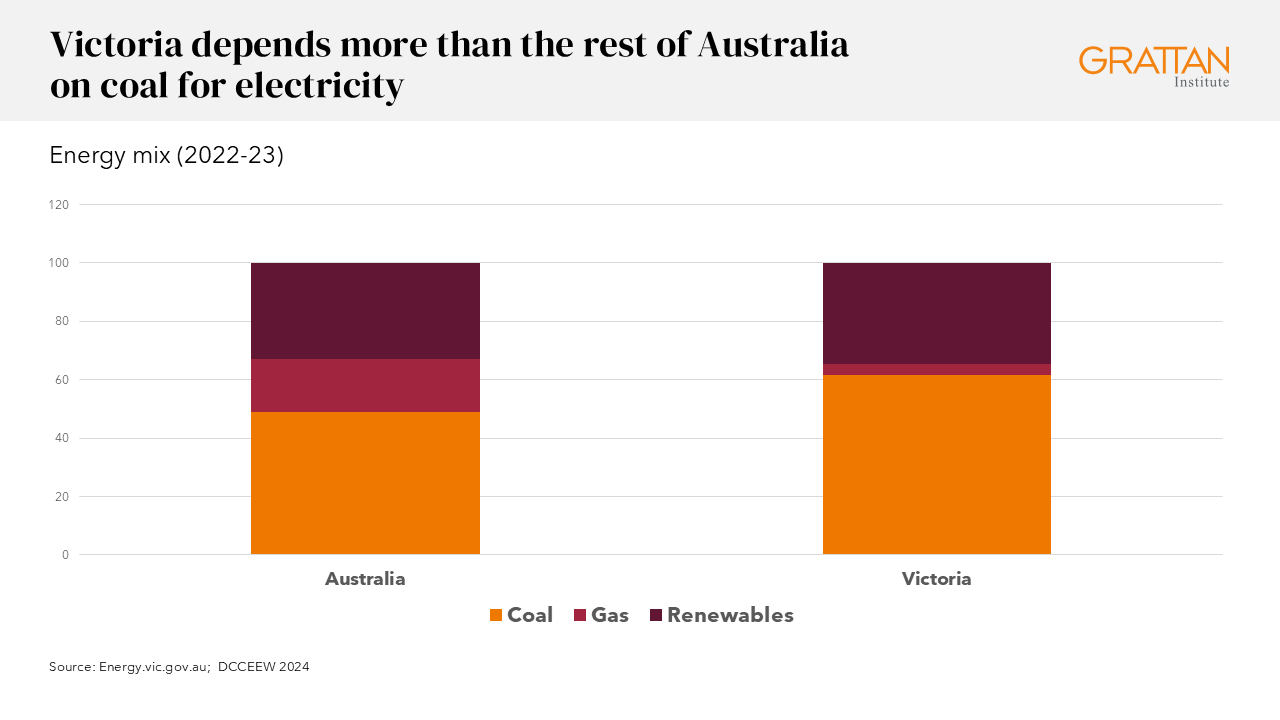

1. Victoria depends on coal

Low-cost brown coal power stations have dominated Victoria’s electricity supply for many decades, and they still do. It was the low cost of this technology that caused the State Electricity Commission to decide against a nuclear power station on French Island in the late-1960s.

Victoria has seen a steady decline in the importance of manufacturing. In 2007, manufacturing contributed 12 per cent to gross state product, only half the level of the 1960s.

By last year, that contribution had more than halved again. Manufacturing built on low-cost fossil fuel is no longer a driver of the state’s prosperity.

But reliable, affordable energy remains critical for homes and businesses. Of Victoria’s three remaining coal plants, Yallourn and Loy Yang A are expected to close by 2035, and Loy Yang B by the mid-2040s.

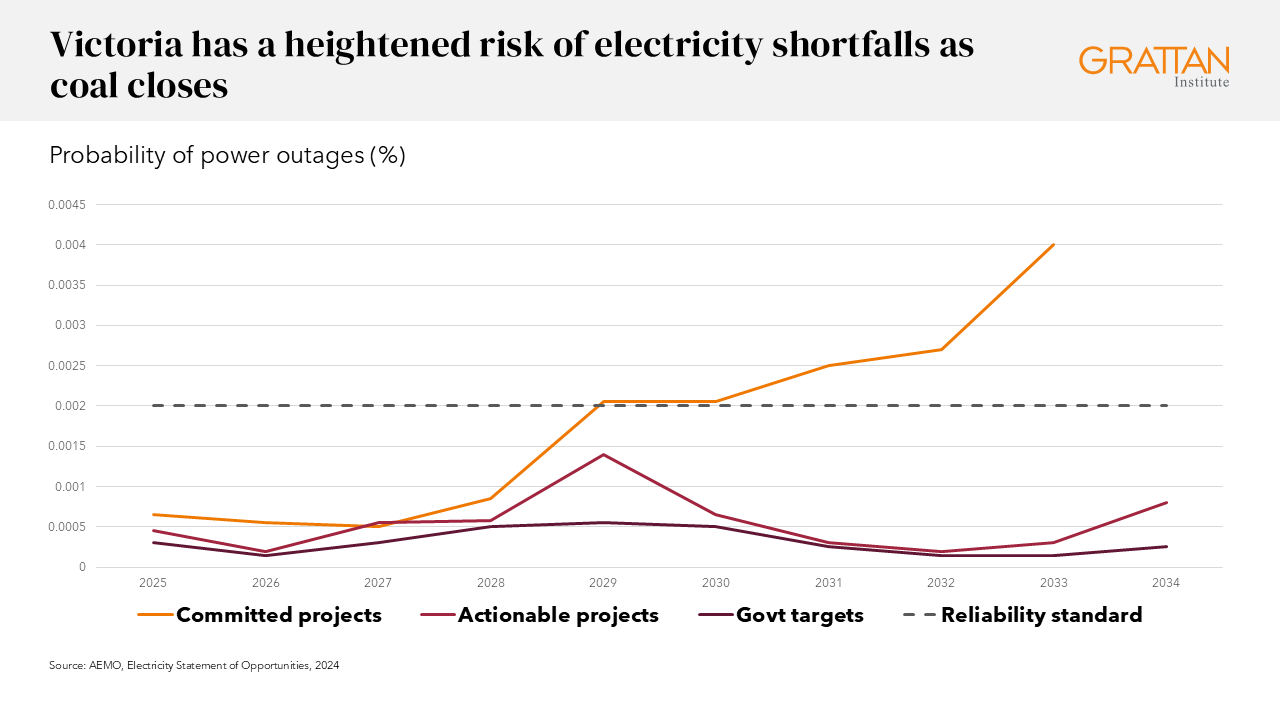

New investment in low-emissions generation, transmission, storage, and gas is not emerging fast enough to replace this capacity, meaning there are risks of power shortfalls unless things change.

2. You can only privatise once

Alongside the establishment of the national electricity market in the late 1990s, Victoria led the country in privatisation and competition policy. The state’s finances were stretched, and asset sales were attractive to the Kennett government.

Australia was also implementing the National Competition Policy based on the 1993 Hilmer Review, aiming to promote microeconomic reform and enhance competition across various sectors, including energy. It worked – power prices were low and stable, and power supply was reliable.

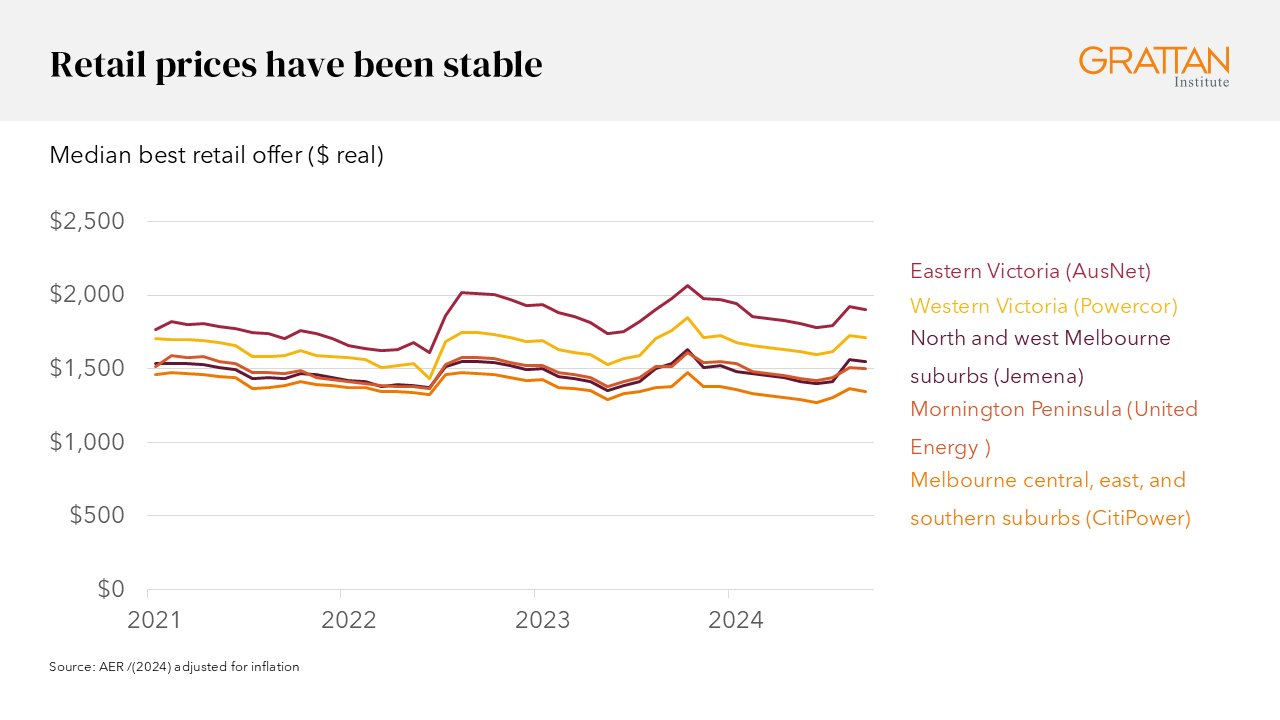

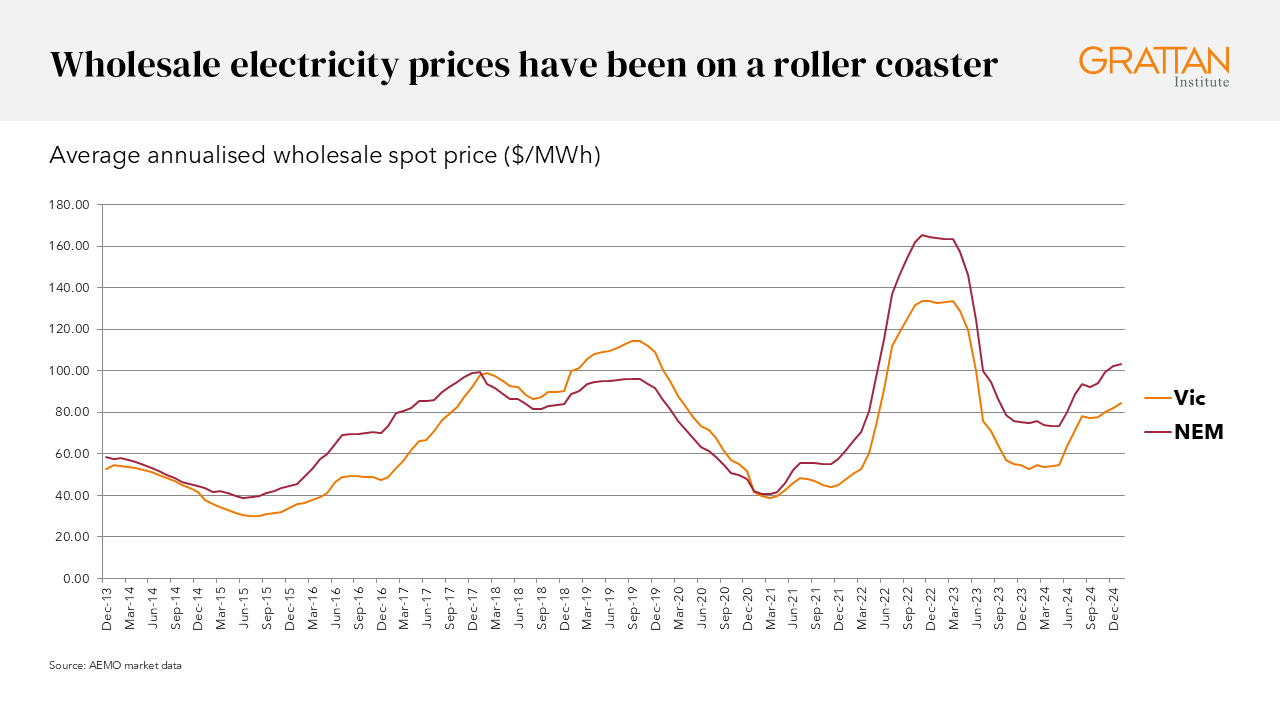

Victoria has benefited from its low-cost brown coal and its connection to three neighbouring states such that its wholesale power prices have generally been low, although that was tested after the Hazelwood plant closed in 2017.

None of the states in the national electricity market avoided the big price lift in 2022-23 that followed concurrent shocks from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and volatile weather in mid-2022. However, at that time and since, Victoria has fared a lot better.

Wholesale price volatility has been muted in its impact on consumer prices that are now, in real terms, about where they were at the beginning of the decade.

3. Victoria is running out of gas

The Gippsland Basin, offshore eastern Victoria, has been a valuable source of oil and gas for more than 50 years. Depletion of that resource was forecast early this century, and now the depletion is accelerating.

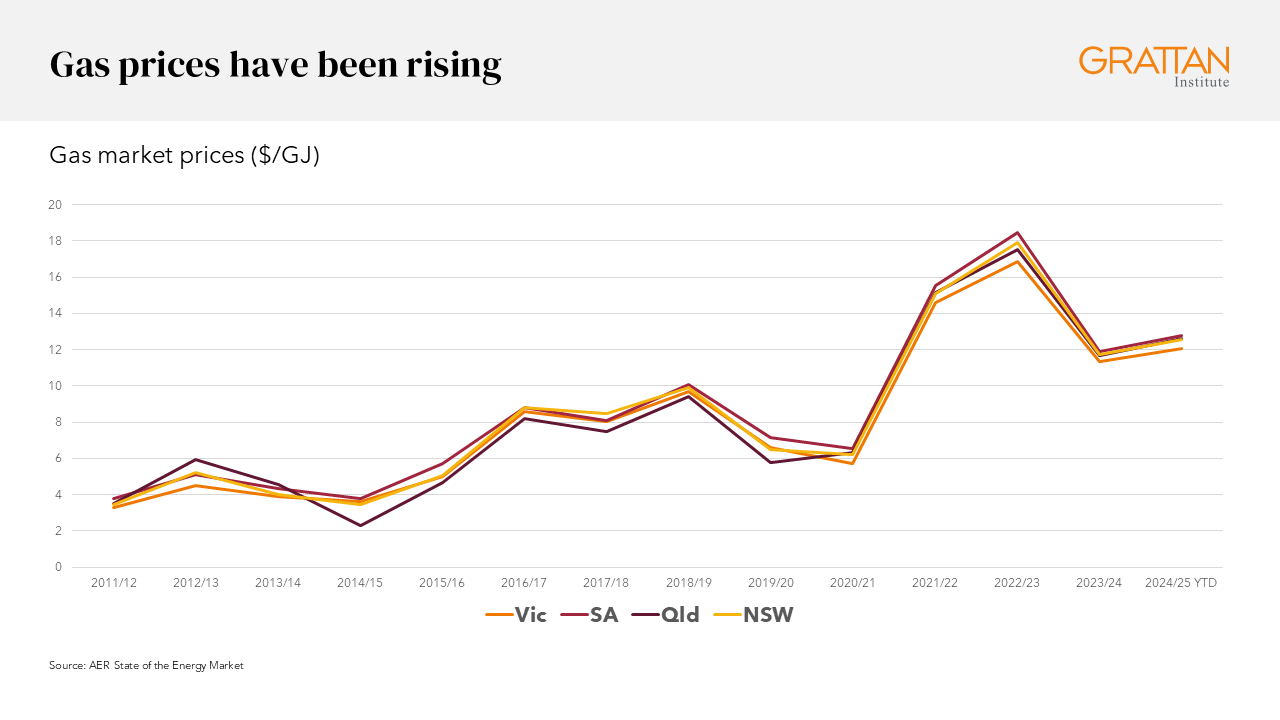

The joint production of oil and gas fuels meant gas prices were low for most of this production history. But as the resource depletion became clear, new discoveries were few and small, and both sides of politics placed restrictions on onshore gas development, prices began to rise. Esso Australia ended 55 years of Gippsland oil production in December last year.

Pipeline capacity to bring gas from other states is limited, and proposed facilities to bring LNG into the south-east have failed either to get commercial sales arrangements in place or to secure regulatory approvals.

The result is that south-eastern Australia, markedly Victoria, faces the risk of gas shortfalls in coming years.

Things were exacerbated when the east coast gas market, linked to international prices through the newly created Queensland LNG export facilities, were hit by price shocks created by the war in Ukraine.

Victoria faces a gas triple threat. First, less than 20 years ago, gas was cheap and solar electricity was expensive, but that position has now been reversed.

Second, gas is a fossil fuel whose extraction and combustion contribute materially to Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions and must be phased out.

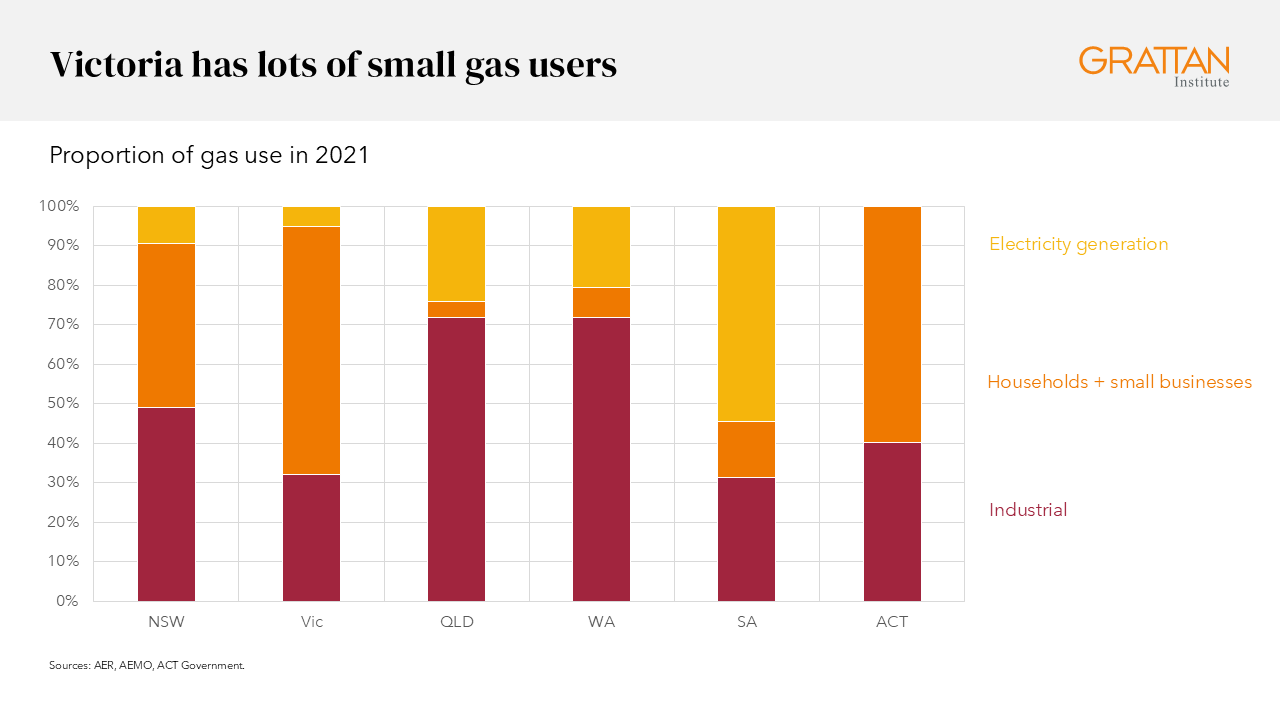

And third, as described above, Victoria is running out of gas faster than it can stop using it. One reason is that Victoria is unusually dependent on gas for 2 million homes and small businesses, with heating being the major application.

This dependence creates an unusually difficult political problem for the Victorian government.

4. What needs to happen

Turning to future opportunities, Victoria’s Renewable Hydrogen Development Plan shows no more progress than similar plans elsewhere.

The cost barrier to producing green hydrogen is proving difficult to crack, and few customers are yet ready to pay a premium for green steel, alumina, fertilisers, or explosives.

Victoria does not have the scale of mineral resources enjoyed by other states to take a strong role in the Australian energy superpower story.

Victoria’s energy challenges flow primarily from stopping the burning of high-polluting brown coal to mitigate climate change. Victoria has clear targets to meet this necessity, and policies are having an impact.

In recent years, Victoria has experienced climate change through floods, bushfires, and severe storms. The electricity system has been directly affected by this extreme weather.

While its fiscal position is under stress, Victoria’s power grid is physically well-positioned with transmission connections to three other states. This gives the state considerable flexibility to import or export power as the market responds to changing weather and market conditions.

Victoria also has significant solar and onshore and offshore wind potential. There is time to implement clear and predictable policies to get the state on track to a net zero future. A successful way forward begins with accepting the nature of the challenges. From that position, a suite of actions should follow.

The state government should:

- Clearly and consistently outline for Victorians the facts, challenges, and opportunities that lie ahead, and the consequences that will flow from success or failure.

- Ensure that the planned interstate electricity transmission lines and intrastate renewable electricity zones are being developed in line with the state’s emissions reduction targets. Closure of coal plants can proceed only when the low-emission renewable generation capacity, storage, and backup gas are in place. Progress to date has been far short of what is required, due to a combination of high costs, slow regulatory processes, and poor consultation with regional communities.

- Tackle the looming short-term gas shortfall risk by working with the federal government and the gas industry to develop and implement a plan that most probably will require specialised terminals to bring liquefied natural gas from sources outside Victoria. At the same time the government must progress the longer-term task of moving 2 million gas users away from the fossil fuel and towards electricity.

- Develop and implement an economy-wide climate change adaptation plan to respond to and plan for global warming that is locked in.