Published by The Australian, Thursday 26 July

For all the political noise about rising energy bills, Malcolm Turnbull and Bill Shorten would do well to focus more on the obscene superannuation fees paid by Australian savers if they want to save households some real money.

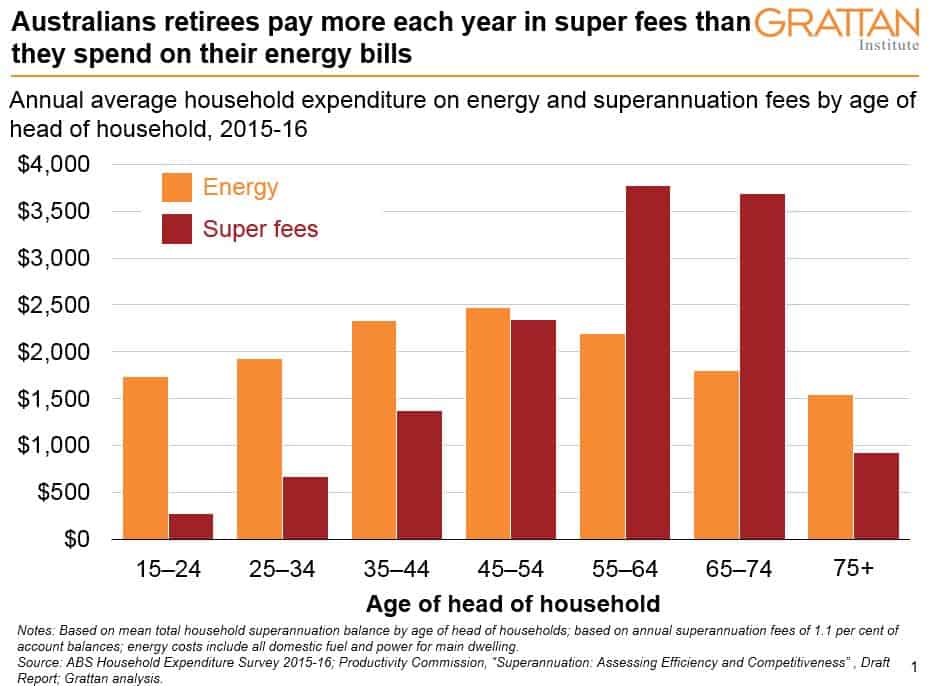

Australians pay more than $30 billion a year in super fees, almost 2 per cent of Australia’s annual gross domestic product. That’s much more than the $23bn we spend on energy. A household nearing retirement pays average superannuation fees of $3700 a year, about the average energy bill. Turning the heater on for longer can hit the household budget for the winter months, but super fees that cut into retirement savings have a lifelong effect on retirees’ finances.

So why are we paying so much for the sector to manage our money? The recent Productivity Commission inquiry into the superannuation sector was scathing. It found there were too many unwanted accounts, too many underperforming funds and too many funds charging exorbitant fees. One-third of all super fund accounts (about 10 million) are unintended multiple accounts. Almost half of Australians aged 40 to 45 have two or more super accounts. These erode members’ balances by $2.6bn a year in unnecessary fees.

Almost five million super accounts are in high-fee funds, costing $1.3bn a year more than low-fee funds. The Productivity Commission also found that super funds with higher fees tended to deliver lower investment returns. The difference between choosing a high and low-performing fund is worth $635,000 for a typical full-time worker by retirement.

Superannuation also costs a lot in poorly targeted life and income insurance. Of the 12 million Australians with life, total and permanent disability or income protection insurance through their super, about a quarter are unaware. Almost 20 per cent of members have duplicate insurance policies across multiple super accounts. Some members may not even be eligible to claim on these “zombie” policies.

The long-term consequences of superannuation policy failures are enormous. The lowest-cost funds today charge fees of about 0.5 per cent of super fund balances annually. Were all funds this efficient, it would boost the retirement savings of a typical full-time worker in a poor-performing fund by about $100,000. Avoiding multiple insurance policies paid through super could boost retirement balances by more than $50,000. For many retirees this is the difference between staying at home for the winter and enjoying a holiday in the sun.

Past reforms, such as MySuper, have been timid. They’ve helped bring down total super fees from 1.3 per cent of total super assets in 2010 to 1.1 per cent in 2016, but total fees still are well above the OECD average.

Thankfully, the government finally may be ready to act.

The Turnbull government’s draft legislation before the Senate promises to curb egregious fees charged on inactive accounts and default insurance offered to those who don’t need it.

If passed, the bill will stop super funds from defaulting many Australians into insurance they don’t need. Life insurance no longer will be a default for super fund members aged under 25, for members with balances under $6000, and for members whose accounts have not received a contribution in 13 months and are inactive.

Life insurance is unlikely to be appropriate for most under-25s, who generally don’t have dependants. Only 6 per cent of people aged 23 or 24 and in employment have a child. If a 23-year-old dies, it is unlikely that any partner will depend on income support from them for the rest of their lives. The super industry argues the proposed changes to default insurance will lead to large increases in insurance premiums.

This strongly suggests that those who are young, have inactive accounts or small balances are cross-subsidising everyone else.

The bill also will consolidate inactive accounts automatically. But even then we’ll still have some of the highest superannuation fees of any system in the OECD. And underperforming funds still will cost retirees billions each year in forgone retirement income. More action is clearly needed.

The Productivity Commission’s recent draft report on super fees sets out a path.

Under the commission’s recommended reforms, Australians would be allocated a default super fund only once, when they first started working. Unless they actively chose another fund, new workers would be defaulted into one of a shortlist of “best-in-show” funds selected by independent experts. They would stay in this fund even if they changed jobs. Financial planners also would be encouraged to recommend funds from the top 10 list or to show reasons why they hadn’t, under a rule known as “if not, why not?”.

But such progress will require both sides of politics to eat some of their own. Many smaller industry super funds would lose the flow of default members delivered by the existing awards system. Without new members or fees on inactive accounts, many would have to merge. Meanwhile, the commission’s best-in-show list for allocating new workers to default funds would likely be dominated by industry super funds, which have tended to outperform for-profit funds. That would be bad news for many for-profits, and for some in the Coalition government concerned about alleged links between industry funds and the ALP.

But difficult as the politics may be, solving superannuation is probably easier than solving the energy policy wars. And it’s even more important.