Published by Pursuit, Monday 29 May

House prices have risen to dizzying heights and Australians have got themselves into more debt than ever. But Australia’s latest housing boom may soon be over, so it’s time to ask: what happens if house prices fall?

Many commentators are focusing on the risks a cooling housing market poses to Australia’s banks. But what about the risk to Australia’s economy?

Bubble or not, there are good reasons why housing is so expensive

After surging for five years, our hot property market may finally be cooling. House price growth is slowing in Melbourne and Sydney, the two epicentres of the boom. New lending volumes are down following a clampdown on interest-only loans. And there are now concerns that apartment prices could fall in parts of Brisbane and Melbourne because of an oversupply.

But talk of a “bubble” that might soon pop misses an important point. Yes, house prices have risen rapidly – by more than 40 per cent nationally and 70 per cent in Sydney over the past five years, but there are good reasons why housing is so expensive today.

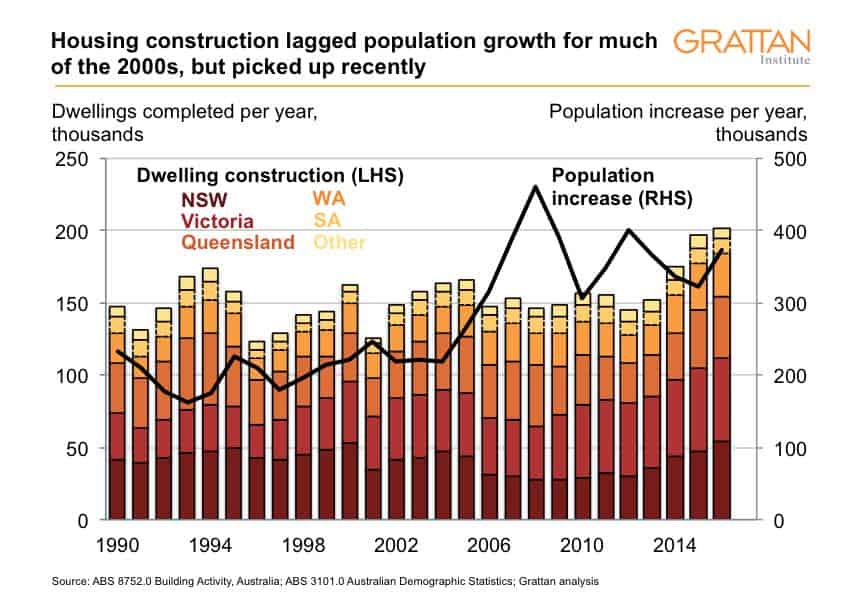

In the past decade Australia’s population has surged by about 350,000 a year, up from the 220,000 a year over the previous decade. Record low interest rates have made it possible to service much larger mortgages. And most of the increase in house prices reflects restrictions on the effective supply of residential land – both limits on rezoning for urban infill and limits on developing land at the urban fringe.

Dwelling construction has simply not kept pace with surging demand. Several years of housing construction – probably at even faster rates than currently – will be needed to erode the large backlog that accumulated between 2006 and 2014, estimated to be a shortage of about 200,000 dwellings.

Investors are also part of the story. Emboldened by recent price rises and armed with cheap credit, they have chased further house price gains. Investors account for 40 per cent of all new mortgage credit. Negatively geared property remains a popular investment strategy. And with gross rental yields below 3 per cent in Melbourne and Sydney, such investments only make sense if investors are banking on future capital gains, or a large rise in rents.

A slow down?

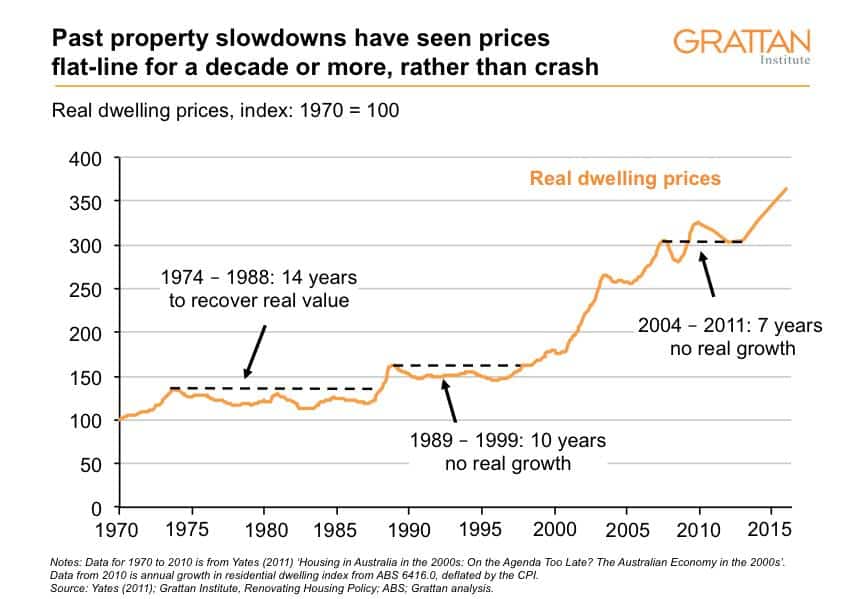

Of course no one can predict with certainty what will happen to houses prices from here. But history provides some pointers. Past Australian housing booms have tended to end with prices falling modestly, or flat lining for an extended period, rather than crashing down. Sharper falls are certainly possible – as the U.S. and European experience during the Global Financial Crisis shows – but are unlikely in Australia while our regulators keep a tight rein on bank lending practices, or unless we are hit by an economic downturn unrelated to housing.

But what might happen to the banks, and the economy, if house prices do start to fall or if households struggle to make good on their debts?

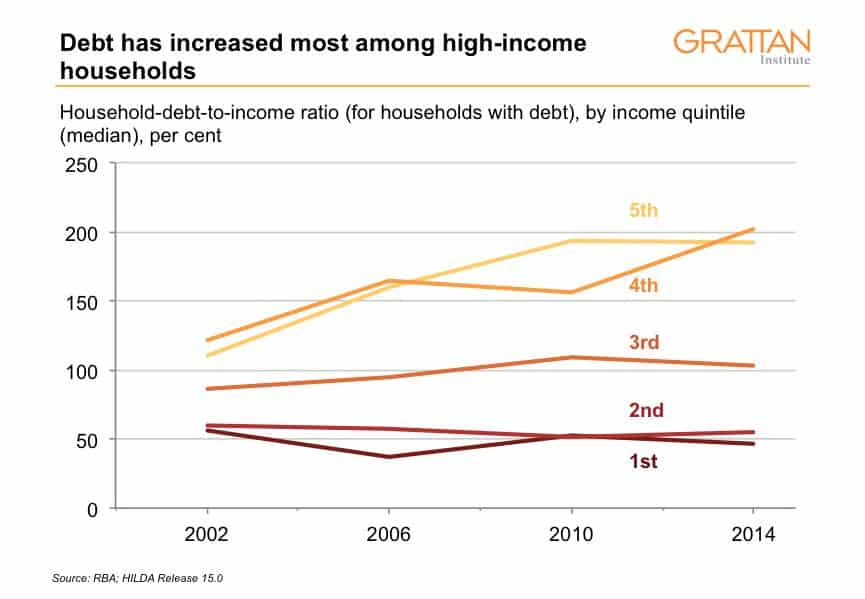

Since the U.S. subprime mortgage crisis, commentators have tended to focus on the risks that property market booms and busts pose to the banking sector. Higher levels of debt increase the risks of borrower default and thus the risks of banks getting into trouble, with all the economic chaos that would create. And household debt in Australia is now a record 190 per cent of household after-tax income, up from about 170 per cent between 2007 and 2015. In 2002, 20 per cent of households had debts of more than twice their income; today it’s 30 per cent.

But the risks of Australian banking instability are low because relatively few households have high loans-to-total-assets ratios, and our banks have strong profits and are well capitalised by international standards. As Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe noted in a recent speech, it’s the riskiest borrower who gets into trouble first in a downturn. And most of those taking on larger debts in Australia appear to be from wealthier households well placed to service those debts.

Regulators are more concerned about households than the banks

Of course there is always a risk that banks drop their lending standards as they compete for business. That’s why Australia’s banking regulator, the Australian Prudential and Regulatory Authority (APRA), is now limiting banks’ new interest-only lending to 30 per cent of total new residential mortgage lending. This followed its move in late 2014 to limit growth in each banks’ total lending to property investors to no more than 10 per cent each year. And APRA may soon require banks to hold more capital against their loans, in line with recommendations from the 2014 Financial System Inquiry to make our banks’ capital ratios “unquestionably strong”.

We should be more concerned about the risk that much higher debts prompt a rapid fall in household spending in the event of a downturn. Household consumption accounts for well over half of GDP. Recent RBA research shows that households with higher debts are more likely to reduce spending if their incomes fall.

A rise in unemployment, perhaps prompted by a slowdown in China or a stuttering U.S. recovery, would force many people to save more – and to consume less.

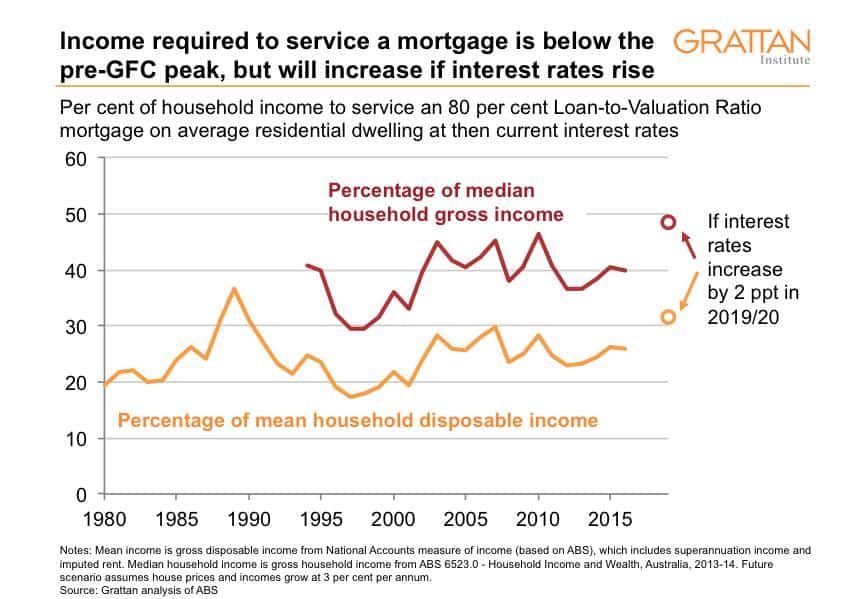

A related risk is that even a relatively small rise in the interest rates paid by households would crimp their spending. Grattan Institute research shows that if interest rates rise by just 2 percentage points, mortgage payments on a new home will cost more of a household’s income than at any time in the past two decades. While the RBA would only lift interest rates cautiously, another disruption to international financial markets such as in 2008 could see banks’ funding costs rise sharply, raising mortgage rates.

Falling house prices may also result in reduced consumption if homeowners feel poorer. But estimates of the size of this effect vary widely. One recent RBA paper estimated that each dollar of housing wealth lost reduced household consumption by about a quarter of one cent, implying a 0.1 per cent fall in GDP for each 10 per cent fall in house prices. Another paper suggested such a “wealth effect” could be ten times as large.

So how should policymakers respond to these risks?

First, the RBA needs to be extra careful should it feel the need to raise interest rates in future. Higher debt levels mean household spending is likely to fall more when interest rates rise than it did in the past. Perhaps the RBA should make smaller shifts in the cash rate – such as 10 basis points – to cushion the impact of future rate rises.

Second, Australia’s financial regulators – APRA and ASIC – need to be ready to clamp down on banks making risky loans if there are signs that lending practices are deteriorating. But that doesn’t mean lending should be restricted just to bring down house prices.

Third, the Commonwealth Government needs get its fiscal house in order. Australia urgently needs a better budget position so we have more room to manoeuvre. The Australian economy is particularly exposed: with interest rates at historical lows, there are limits to what the RBA can do to stimulate growth, so fiscal stimulus will be an important part of any response to a future economic shock.

Published by

Published by