Summary

The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) is failing many disabled Australians who need the most support. About 43,500 people with intensive support packages are seeing little benefit from a scheme that was supposed to give them greater choice and improved independence.

Download the accessible text version

The only option for many of these people with profound disability is to live in group homes – where they are at high risk of violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation.

The costs of supporting these 43,500 people is at least $15 billion per year, with average costs per resident of more than $350,000. That’s almost 40 per cent of the total costs of the NDIS for only 7 per cent of its users. Governments need, and disabled people deserve, far better services for this price tag.

Last year’s reports from the Disability Royal Commission and the NDIS Review called for significant reform and a wider range of housing and support services. But neither report provided a clear and detailed roadmap to improve people’s safety and give them alternative options.

There are better and cheaper alternatives to group homes, but they are not widely available, in part because NDIS policies are too rigid and its funding too inflexible. Other countries, including the UK, the US, and Canada, have successfully reformed disability housing and introduced new living arrangements which offer people greater choice and a more individualised approach.

Four big changes are needed to improve housing and support for Australians with intensive needs.

First, the National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) should give more support to alternative options, such as those that are working well in Western Australia and overseas, and help more disabled people into ordinary housing in the community.

Second, the current group-home model should be reformed so people who want to share their support can choose who they live with and control how services are provided in their home. Larger group homes should be phased out within 15 years.

Third, the funding process needs to be reformed so people who need intensive support at home get more help to understand their options and navigate the system. People should get early access to an NDIS-funded budget that they can use flexibly, within an overall funding envelope that is affordable for government.

And fourth, the NDIS regulator should step up to ensure the people who depend on these services are safe and have real choice. Specific practice standards should be developed for shared housing and individualised living, with mandatory inspections to make sure the standards are being met and the residents are safe.

Creating more options and better help for people to choose housing and living supports would be a win-win. It would transform the lives of Australians with the most profound disabilities, and it can be done efficiently to help make the NDIS more sustainable for future generations.

Getting this right should be a litmus test for any government seeking to get the NDIS back on track.

Recommendations

1. Create innovative alternative housing and support options, to increase choice and improve sustainability

- Foster a new category of ‘semi-formal’ supports such as home-share and hosts, that enable more individualised living arrangements within current budgets.

- Establish a new housing payment for people with intensive housing and support needs leaving group homes, or who do not qualify for current specialised housing. People could use the money to help them to live in ordinary community homes.

- As an incentive to establish more efficient housing arrangements, allow people to keep any money they save and use it to buy other supports and services.

2. Reform group homes so that people sharing support have more autonomy

over their home life

- Improve the training of staff in shared accommodation, to maximise residents’ quality of life.

- Ensure residents can make collective decisions about how their households are run, by mandating governance arrangements that put the residents in control.

- Require enforceable service agreements in shared accommodation, and require the separation of housing and support so people can choose or change their support provider without putting their tenancy at risk.

3. Improve planning, budget setting, and service coordination

- Create a dedicated pathway for eligible people that streamlines assessment processes and gives people timely access to a consistent budget before planning commences.

- Introduce specialised housing and living navigators, to help people develop their plans, choose their supports, and navigate the system.

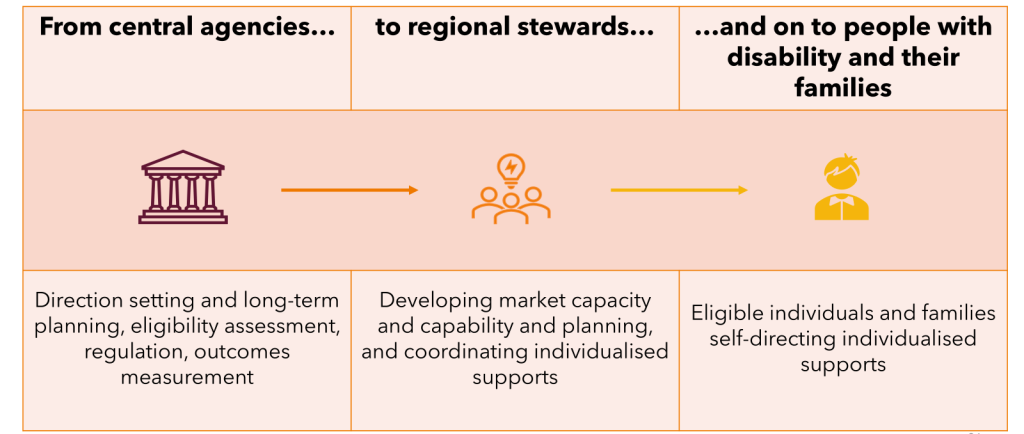

- Establish regional hubs to steward the market and commission services. Each hub should have a dedicated fund to accelerate innovation and support promising approaches.

4. Increase guardrails and accountability

- Require all providers of housing and living supports to register. Introduce random inspections of their services, and report regularly on their performance.

- Produce better data on people’s living arrangements as they transition out of group homes.

- Develop specific practice standards for shared accommodation and individualised living arrangements, and conduct inspections to make sure the standards are being met and the residents are safe.

Chapter 1: Disability housing and support is failing those who need it most

One of the NDIS’s most important responsibilities is to provide support to Australians with disability who need extensive help at home with everyday activities. Yet many people who get this support from the NDIS get care that is unsafe and low-quality – despite eye-watering cost.

Many people with profound disability who aren’t in their family home live in group homes, where they share supports with other disabled people. Often they have little say over who they live with or how their support is provided, and too frequently they are subjected to violence, abuse, and neglect.

The NDIS promised more choice and innovation in services, but since it was introduced more than a decade ago, little has changed in the lives of people with profound disability. We need to do better, and we can.

This report lays out why reforming housing and support for these Australians is so important, and what government needs to do to improve current services while creating better, safer, and more sustainable options.

1.1 Disabled Australians with the highest needs rely on the NDIS for housing and support

In 2013, the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) was set up to provide funding and support to people with significant and permanent disabilities.1 These supports are critical for disabled people to lead independent lives as members of the Australian community.

Some people need very high levels of support from the NDIS to live at home. Many disabled people will never require this level of support.

Figure 1.1: Who receives intensive living support?

| A small group… | typically with intellectual disability… | and intensive needs… | who need significant support. |

|---|---|---|---|

| People with intensive living support funding make up about 7% of the people in the NDIS | 34% of people with intensive living support funding have an intellectual disability | Active support for more than 8 hours per day and some level of support for other hours, including overnight | Payments to people with intensive housing and living support represent at least 37% of the total cost of the NDIS |

This may be because they are able to live independently with a lower level of support, or because family or friends give them significant help. Our focus in this report is on improving the lives of those Australians who require intensive housing and living support in their home.

People who receive intensive living supports (described in Figure 1.1) typically need eight hours or more of help with daily activities such as bathing, getting dressed, going to the bathroom, preparing food, and eating. They also need some form of support to be available overnight in case of emergencies.

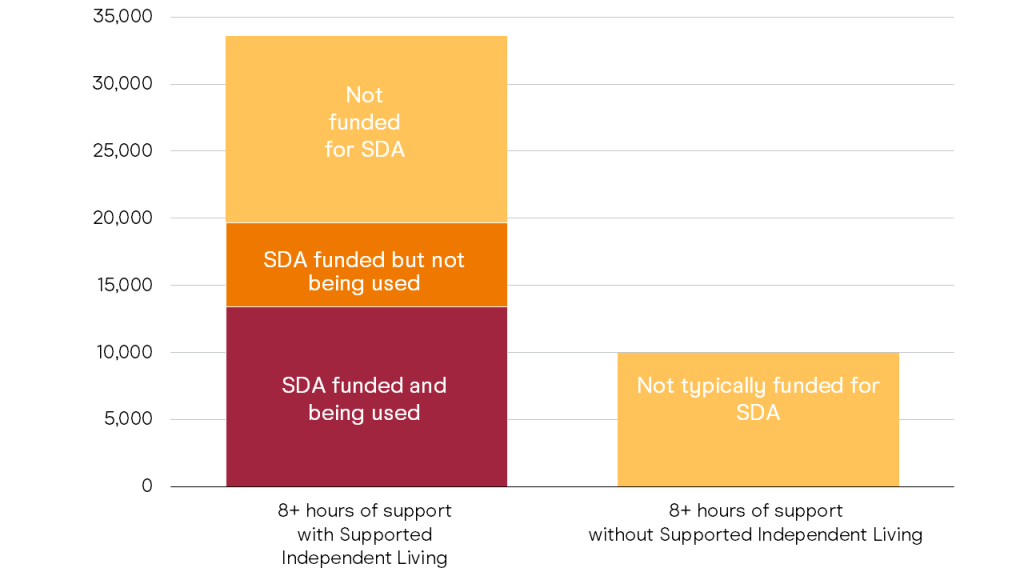

The NDIS provides supports to these Australians through several different funding streams. About 33,500 receive Supported Indepen- dent Living (SIL) funding for shared, in-home supports (as shown in Figure 1.2), often in group homes. Another 10,000 receive a similar amount of assistance with daily life (eight or more hours a day) outside of the SIL category.2

About 22,000 people (mostly from the Supported Independent Living cohort) also receive funding for Specialist Disability Accommodation. This money is to pay for specially designed or modified housing, such as housing that is fully wheelchair accessible or has strengthened ceilings for hoists.

The remainder of people receiving intensive NDIS living supports do not receive funding for Specialist Disability Accommodation because they live with their family and have not requested it, because their home does not need enough physical modifications to qualify for it, or because they are not eligible for it. Many group homes, particularly older ones, do not attract significant, or any, Specialist Disability Accommodation funding.3

About 34 per cent of people receiving intensive living support have an intellectual disability. Another 11 per cent have autism, about 10 per cent have psychosocial disability, and about 9 per cent have cerebral palsy or acquired brain injury. The remaining quarter have conditions including multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, and other physical and neurological disabilities.4

People with intensive living support who don’t have access to Specialist

Disability Accommodation face many of the same challenges as other Australians in finding affordable housing, with rental affordability at a record low.5 Public and social housing waiting lists are long, and housing stress is high and increasing, particularly among people on low incomes.6

Figure 1.2: People with Supported Independent Living in their plan are more likely to live in Specialist Disability Accommodation housing

NDIS participants by funding category, December 2023

Source: Grattan Institute analysis of NDIS data.

1.2 Despite 10 years of the NDIS, too many Australians still live in group homes

It’s most common for people with Supported Independent Living (SIL) packages to live in group homes. These are houses where support is provided for several people under one roof. Many group homes have three or four residents, while some (known as ‘legacy stock’) have six or more people living together.

A group home is not strictly defined by the number of people living there, but rather the institutional culture that characterises many of these arrangements. Group homes often operate more as service facilities than as homes for their residents.

There are 3,302 group homes across Australia that are registered as Specialist Disability Accommodation, with a capacity of more than 14,000 residents.7 Thousands more people live in group homes that don’t attract Specialist Disability Accommodation funding.8

People who live in group homes tend to stay there for a long time. Nearly four out of five people have lived in their group home for decades, having transferred into the NDIS from old state-run disability systems.9

Little has changed for these people since the start of the NDIS, a scheme that should transform the lives of people with profound disabilities.

1.2.1 Many group homes are low-quality and unsafe

Group homes were governments’ favoured housing and support approach for people with severe disabilities when care was moved out of large-scale institutions.10

De-institutionalisation was led by agencies responsible for disability services, which meant that the focus of housing design was driven by the aim of maximising the potential for those services to be shared.11 Housing multiple residents together enabled providers to more easily organise support-worker time, and manage costs by maintaining some economy of scale in service delivery.12

But the more people who live in a group home, the more difficult it is to create a home-like environment and the higher the safety risk.

Instances of abuse perpetrated against group home residents13 are sadly not isolated and have marred the landscape of disability support for generations.

The Disability Royal Commission heard extensive testimony that showed violence, abuse, neglect, and exploitation is common in group homes.14 The NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission found more than 7,000 serious incidents of abuse or neglect over the past four years in a sample of seven of the largest providers of disability group homes.15 Other inquiries by the Senate and Victorian Parliament have also been shown evidence of widespread and consistent abuse.16

While neglect and abuse will be a risk in any disability service, research has shown that group homes increase this risk for their residents.

One international study found that community participation results for group-home residents were no better than for people living in nursing homes.17

Some of the highest-risk elements for group-home residents include:

- A lack of choice over key aspects of their home life, such as who they live with, where they live, and the staff who provide support;18

- Isolation and limited contact with people outside the residence;19 Large numbers of staff providing support to residents;20

- A lack of valued interpersonal relationships between residents and staff providing care;21

- A service culture that puts the needs of staff first;22 and

- Violence between residents in group homes.23

Many of these features are endemic to group homes in Australia.

Many group homes effectively operate as ‘closed systems’, where the landlord is also the service provider. This means residents can lose the roof over their heads if they are unhappy with their support and attempt to make changes to it.24

The committee overseeing the the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities has expressed dismay at the group home situation in Australia, recommending a national framework to facilitate their closure.25

The Royal Commission called for major reform in disability housing and support, and a majority of commissioners recommended group homes be phased out over the next 15 years.26

Despite extensive documentation of problems in group homes, there is no nationally consistent data on who is living in them and the prevalence of mistreatment and abuse. And little is known of the quality of support provided, with no commonly adopted quality measures, benchmarking, or performance reporting specific to these settings. As a consequence, Australians are in the dark about what happens behind the group-home door.

What we do know is that the Royal Commission and the NDIS Independent Advisory Council both concluded that ‘while there was significant variation in the quality of group homes, even the best group homes were not that good’.27

1.3 Costs are high and rising fast

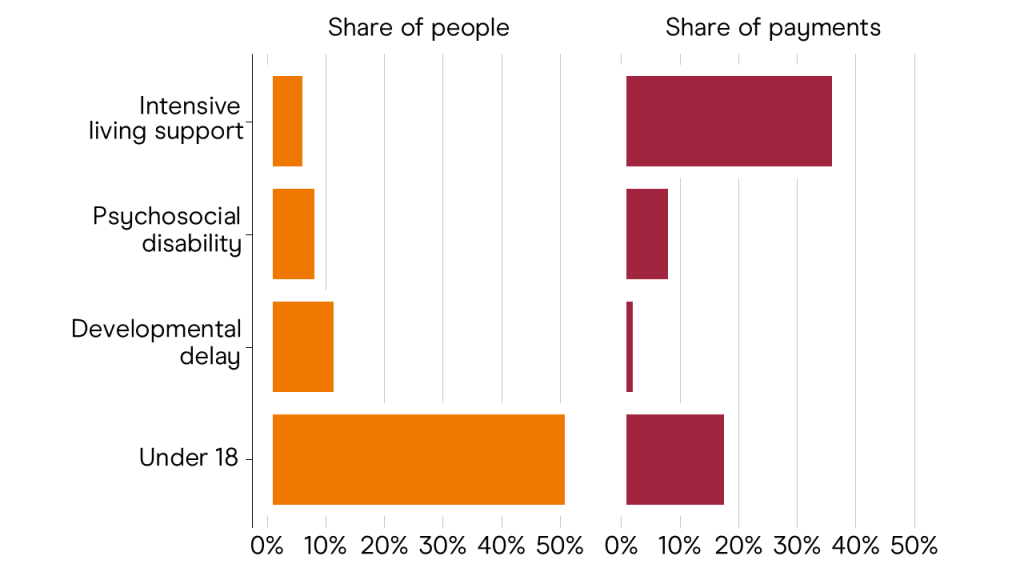

Support for people who need intensive housing and living supports is the most costly part of the NDIS, totalling at least $7.7 billion of payments for the six months ending September 2023.28 That’s 37 per cent of total NDIS payments going to about 7 per cent of people in the scheme.29 Despite their small number, people with intensive housing and living supports cost the NDIS more than those without it who are under 18, or with psychosocial disability and developmental delay combined (Figure 1.3).

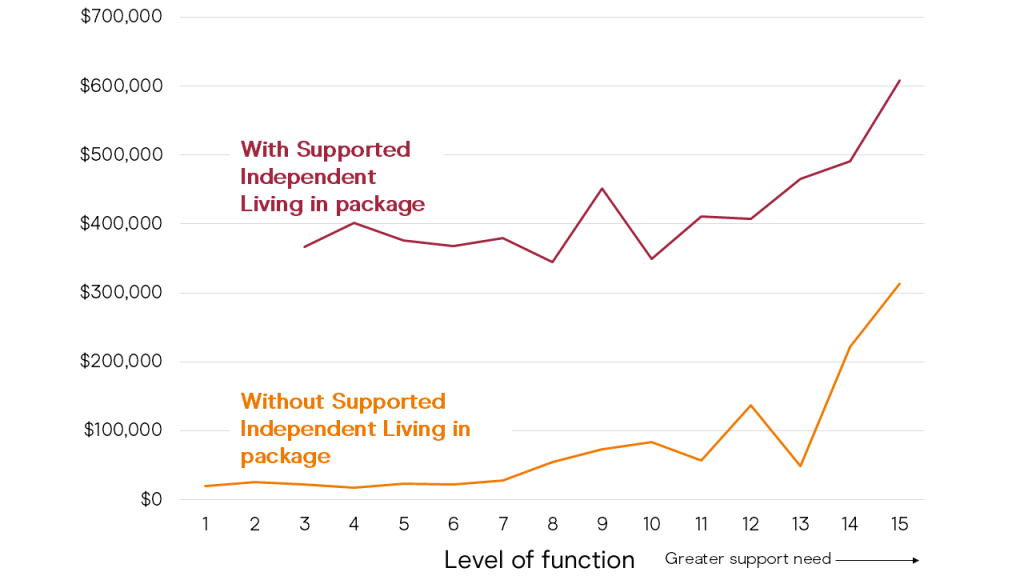

The way people get support is an important factor in how much it costs. The plan sizes of people with the highest support needs vary significantly depending on whether they have Supported Independent Living funding or not – jumping from $313,000 without it, to $608,000 with it (Figure 1.4).

When people get Supported Independent Living funding, their package size increases dramatically, reflecting the higher costs of supports for people no longer living with their family.

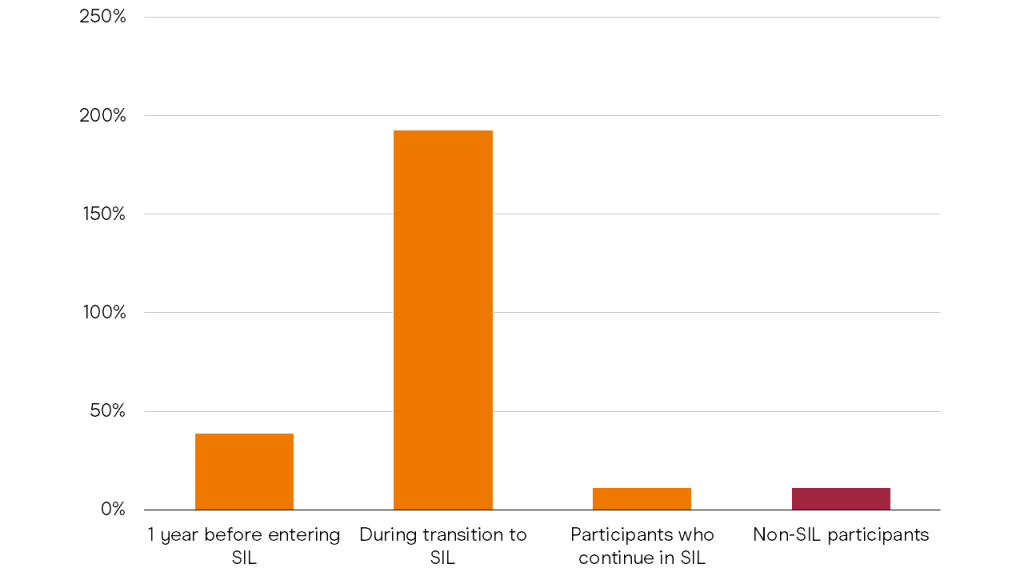

The costs for a typical person who transitions to Supported Independent Living from other NDIS supports, such as when support in the family home becomes unsustainable, will increase by nearly 200 per cent during the year of the transition, compared to annual rises

of 11 per cent for people without this type of funding (Figure 1.5 on page 13).

Finding more efficient ways to provide housing and living support while improving quality and safety is therefore critical to the sustainability of the NDIS.

Figure 1.3: Despite attention on other groups, people receiving intensive living support cost a disproportionate amount to the NDIS

September 2023 for Intensive living support, June 2024 for other groups

Source: NDIA (2024b).

1.3.1 More people are becoming eligible

Costs are also increasing because more and more people are becoming eligible for housing and living supports each year.

Every year, the NDIS actuary estimates how many people will need Supported Independent Living funding, and in the 2022-23 year there were 3,500 more than expected.30

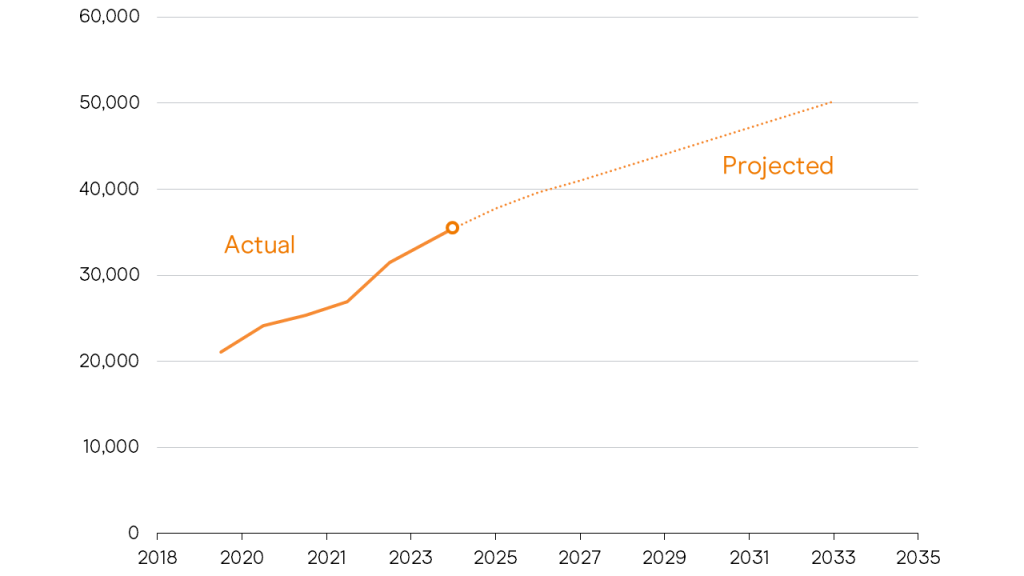

The number of people getting Supported Independent Living funding is projected to further increase steadily as more parents from the Baby Boomer generation grow too old to care for their children and people age within the scheme. The number is projected to be more than 50,000 by 2033, compared to about 34,000 today (Figure 1.6 on page 14).

1.3.2 Providers are struggling

Despite higher numbers needing support and rapidly escalating costs, many providers face challenges balancing their books, with some reporting multiple-year losses.31

Providers have identified rising vacancy rates in older housing stock, shorter resident tenure, and rising labour costs as factors cutting into their revenue.32

Without serious reform, it is likely that providers will continue to struggle to make ends meet, posing further risks to the quality and continuity of support for people with intensive needs.

Figure 1.4: Supported Independent Living funding greatly increases people’s NDIS package size

Median package size by level of function (a measure used by the NDIS to indicate the level of a person’s disability), 2023

Source: ABS (2023a).

1.4 Money doesn’t always go to the people who need it most

While total costs are through the roof, individual funding decisions are inconsistent and inequitable, with little relationship discernible between funding and need.33

Most people who receive Supported Independent Living funding live in group homes, and these tend to have staffing requirements that don’t relate much to need. For example, a three-person group home will usually be required to have a staff member present 24/7, regardless of how much work there is to do.

As a result, people with different care needs have no difference in package size. Funding only starts to increase for people with extremely high care needs (Figure 1.4 on the previous page).

1.5 The need for change is clear

Recognising the seriousness of the problems facing the NDIS, the Albanese Government commissioned an independent review into the design, operations, and sustainability of the scheme. The review has recommended several relevant reforms:

- More help for families to navigate their way through the system, understand their options, and get the support they need;

- More transparent decision making and budget setting;

- More flexibility for people in how they can use their allocated housing and living funding;

- An expansion in the number of people who can get Specialist Disability Accommodation funding;

- Accelerating the move to ensure all new homes meet a minimum national standard for accessibility;

- Strengthening regulation so all people in group homes and other shared accommodation are safeguarded against violence, abuse, and neglect.

Figure 1.5: Costs rise steeply when people receive Supported Independent Living

Change in size of package from year-to-year

The review also sets the ambition to shift to a system where people ‘always have a say about their living arrangements and the supports they receive, in line with community norms and within the bounds of their allocated budget,’34 but its recommendation that these budgets be pegged to the cost of each person sharing support with two others has left many unsure how this change will be realised.35

The government has committed $468.7 million over five years to help get the NDIS back on track, including $20 million over two years to commence consultation on and design of a new service navigation approach, and a further $129.8 million over two years to consult on other review recommendations, including those relating to housing and living supports.36

1.5.1 Moving away from group homes is possible and desirable

While the recommendations made by the NDIS Review could lead to some improvements, they don’t provide a sufficient roadmap for how to transform group homes and create alternative housing and support options.

And yet, there are tens of thousands of disabled people – some who already have housing and living supports, and some who are yet to need them – who would benefit from this greater choice.

Figure 1.6: The number of people who require Supported Independent Living funding is expected to keep rising

Number of people with Supported Independent Living funding

There are more than 250 large group homes in Australia, sometimes called ‘legacy stock’. These are mini-institutions housing from six to 20 people at a time, removed and isolated from the community.37 These group homes were administratively transferred into the NDIS, but their residents were never offered anything different. Most of these people live in the same conditions now as they had more then a decade ago.

There are also an estimated 17,000 people living at home with a household member over 65 providing unpaid care who will need intensive support at some time in future.38 As their Baby Boomer parents age, increasing numbers of parents will no longer be able to care for their disabled adult children.

Both of these groups of people deserve to have choices about where to live and how to receive support. But without a clear plan, it is unlikely they will see any change.

1.5 Reform efforts so far have faltered

A combination of factors has meant that innovations in NDIS housing39 and support have yet to materialise at scale or crystallise as widely available alternatives to group homes. These factors have included:

- No strategic priority to advance innovation or reduce reliance on institutional support models;

- A lack of funding to trial, evaluate, or spread alternatives to group homes;

- No support or incentives for providers to adjust their business models to offer new things;

- Operational decision making that continues to channel people with intensive needs to group homes due to the perceived necessity of economies of scale in providing their support;

- A lack of active promotion of alternatives by the NDIA;

- A lack of information, advice, and support for disabled people and their families to help them understand their options and coordinate services;

- Policy settings that undermine the financial viability of alternatives, such as denying indexation to innovative arrangements.

We give more detail in Appendix A on why innovative alternatives to group homes have not yet taken hold in the NDIS.

1.7 How the remainder of this report is structured

Chapter 2 identifies alternatives to group homes, and shows that creating a wider range of options could deliver better results for disabled people and greater value for the public purse.

Chapter 3 makes recommendations to transform group homes by transitioning services to share house arrangements that give residents more choice and autonomy over their home life.

And Chapters 4 and 5 set out what else needs to change in the NDIS to make these reforms happen.

Taken together, our proposals are a practical plan to make NDIS housing and support better, safer, and more sustainable.

Chapter 2: Create alternative options

Better living arrangements are possible, even within the NDIS’s budget constraints. Group homes are not the only option, and there are more ways to make supports cost-effective than economy of scale.

And yet, most people who need intensive housing and living supports don’t get the options they need. The current system pushes people into group homes – often the only choice available to disabled people who want or need to leave home. These specialised arrangements are costly and risk segregating people with disability from their community.

Innovative alternatives do exist in pockets around Australia, with people living in neighbouring apartments and sharing a support worker, or on their own with a support worker on-call overnight. But there has been little innovation in how living supports are delivered, and an almost exclusive reliance on paid support workers.

Enabling more people to live in ordinary homes in the community in settings that maximise different kinds of support could improve the lives of people with disability while also increasing safeguards and improving quality – all within the current funding envelope for these supports.

2.1 There are already pockets of innovation across Australia, but they won’t be enough alone

The introduction of the NDIS has spurred some innovation in housing and support options (see Figure 2.1 on the following page for a summary of 12 promising approaches).

Some services rely on people with a disability sharing the same workers, but without living in the same home. This can be most effective where people need only occasional support overnight and are capable of asking for help.

Disabled people in parts of Sydney’s eastern suburbs can call to have a support worker from Spinal Cord Injuries Australia come to their home from 6pm to 5am, with an average 15-minute response time.

This means people who need services overnight (such as a catheter change) can still live independently without paying a support worker to be on site all night.40

If people need more frequent support, some types of Specialist Disability Accommodation enable 5 to 10 people with a disability to live in different apartments in the same building as sole occupancy residents, while sharing support from a single support worker who can

help overnight if there are problems. The support worker typically stays in a separate apartment within the same development.41

The Community Living Initiative in Cairns is a model of housing and living support designed for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability.42 The initiative provides culturally informed support.

A post-occupancy survey indicated improved social and emotional wellbeing for tenants.43

These pockets of innovation are promising; but much more innovation is needed in housing, in the way support is provided, and in the way technology is used. Harnessing these innovations will be key to giving disabled Australians genuine choice over housing and living supports that promote their independence and help make the NDIS sustainable. The remainder of this chapter focuses on the potential of what we call Individualised Living Arrangements.

Figure 2.1: 12 promising examples of innovation that can create alternative options, spanning housing, support, and technology

| Housing | Support | Technology/Remote Services |

|---|---|---|

| KeyRing 10 individuals live in close proximity in the community, comprising nine people with disability and a Community Living Volunteer who lives rent- free in exchange for some support (UK, Vic) | Hosts An adult who needs long-term support is carefully matched with a host, often a family, that provides support, companionship, and a welcoming home life (UK, US, WA) | Occasional and Emergency Service Night call-out service with an average 15-minute response time, enabling people with disability who need services overnight (such as a catheter change) to live independently without a support worker on site (NSW) |

| Community Living Initiative A model of housing and support designed specifically for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability, with support and governance built to create a culturally safe service (Qld) | Home-share A home-sharer lives with a disabled person in their home (rented or owned) and provides support and companionship in exchange for low- cost or free accommodation (Australia, UK, Canada) | Just Roaming Uses sensors to monitor activities in real-time, combined with in-person support from ‘roaming’ support workers (UK) |

| 10+1 10 single-occupancy apartments, integrated in a larger apartment complex, with one additional apartment as a base for support workers who provide onsite shared support 24/7 (Vic) | Good Neighbour Community members are offered reduced rent in exchange for providing informal support to a disabled person living in the neighbourhood, or in the same complex (Canada, WA) | Telecare and Remote Support Uses sensors to enable passive monitoring and check-ins by family or support services, for people with intellectual disability, funded under Medicaid (US) |

| Haven Integrated social housing and support services for people with psychosocial disability, with long-term housing and 24/7 onsite support (Vic) | The Buurtzorg Model Self-organising teams within a neighbourhood, with reduced layers of management, and autonomy to determine the support someone needs to be more self-sufficient in their own home (Netherlands, WA, Qld) | Emergency After-Hours Response Services Overnight telephone support service for non- medical emergencies which can assist with organising in-home support at short notice (Vic) |

2.1.1 The NDIS needs to innovate more with Individualised Living Arrangements

Individualised Living Arrangements (ILAs) are innovative housing and living support arrangements that can give people with disability greater flexibility, independence, and choice. ILAs will typically cost the same as, or less than, a group home, and provide a higher quality of life.

Individualised Living Arrangements differ from group homes in three main ways. They:

- Are integrated into the community as much as possible through the location of housing, living with community members, and building relationships in the local community.

- Use semi-formal and informal support as much as possible, rather than relying solely on formal support.

- Free people with disability from having to share supports.

There are many types of ILAs, including hosts, home-share, co-residents, good neighbour and mentoring, all of which enable people with significant disabilities to live independently in regular homes, with people they choose to live with, with access to the broader community, and often at a lower cost than similar support would cost in group homes.

In Australia and abroad, a growing number of people with disability call Individualised Living Arrangements ‘home’.

Western Australia has pioneered ILAs. Individualised housing and living support has been an option in WA since the 1990s, and today there are multiple approaches tailored to people’s circumstances.

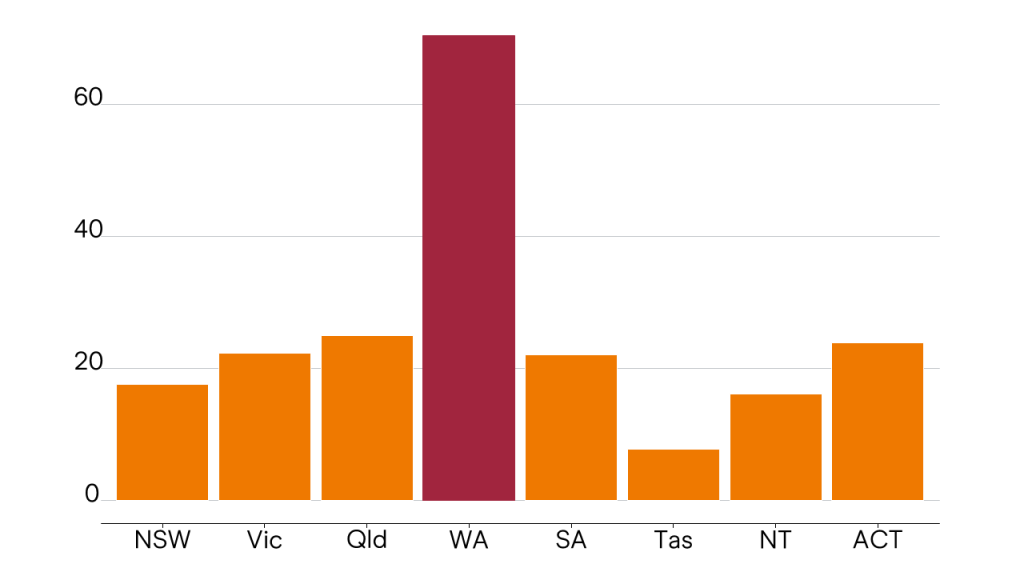

Disabled people in WA have taken up Individualised Living Options at a much greater rate than disabled people in other parts of the country (Figure 2.2 on the next page).

In British Columbia in Canada, Home Sharing is the main type of residential support for people with intellectual and developmental disability funded by the provincial government, overtaking group homes as the most common choice of living arrangement.44 Large institutions were phased out entirely in the late 1990s, and today, more than 4,000 people live in home sharing arrangements – in a province that is only a quarter the size of Australia.45

In the UK, just under 10,000 people were being supported in Shared Lives arrangements similar to ILAs in 2022-23. People with disability either lives full-time with their Shared Lives carer, or they visit as needed. Quality and safety tend to be high in these arrangements: 97 per cent of Shared Lives arrangements in England have been rated as ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’.46 The UK government awarded Shared Lives England funding in October 2023 to expand the program, as part of a fund to increase innovation in adult social care.47

Individualised living arrangements in the US show promising results, with many states having host family arrangements. Of Americans with disability who were receiving residential services and living out of the family home in 2012, nearly 8.6 per cent were living in a host/foster family arrangement (including children in foster care).48

While every Individualised Living Arrangement differs depending on the person’s needs and circumstances, we focus on two main types of arrangement in this report because we think they have the greatest potential for widespread use: hosts and home-share.

2.1.2 Hosts

A host arrangement is where an adult with NDIS funding lives with a ‘host family’ or ‘host flatmate’, who is not related to them, in the host’s home, becoming part of the household.

The arrangement is very similar to how foster care works in Australia today. A host might be a couple or an individual, and they provide semi- formal support while going about their everyday activities.

The host might help with emotional support, companionship, cooking, cleaning, and other household tasks. In exchange, they receive a subsidy for their expenses. Hosts can also receive rental payments directly from the person living in their home.

To facilitate these arrangements, a service agreement is developed detailing the roles and responsibilities of the host, the person receiving support, and the provider facilitating the arrangement. Hosts typically support a single person in their home, except in extraordinary circumstances, such as when two siblings with a disability want to live together.

In addition to support provided by the host, people with disability can also receive other kinds of support, such as informal support from family, friends, or neighbours, or regular shifts from paid support workers who provide drop-in or on-call assistance.

Figure 2.2: Individualised Living Options are most popular in WA, where innovation has thrived

Number of people in the NDIS, per thousand, with Individualised Living Option funding, December 2023

Source: Grattan analysis of NDIA data.

Box 1: Anja’s host family arrangement

Anja* is 23 and has an intellectual disability and needs help with household tasks and planning her days. Anja lives with Sarah and David in a host family arrangement set up by a registered provider and her family.

David works full time and Sarah works part time. Sarah and David do the cooking, cleaning, laundry, and home maintenance. Sarah is helping Anja learn to make breakfast for herself.

During the week, Sarah, David, and Anja usually eat dinner together. On weekends, Anja and Sarah go out to run errands or meet people. Sarah and David are at home overnight if Anja needs help during the night, although this doesn’t happen often. Sarah and David like to host barbeques in their backyard with friends once a month, and Anja is getting to know them all. Anja volunteers two mornings a week at a local op shop and likes to visit her family on Sundays.

Anja’s NDIS plan means she can get four hours per day of one-to-one community activity time with support workers that she has hired, which she uses for personal shopping, going to the gym, and joining community activities or meeting friends.

Being independent, out of her parents’ home, and having the freedom to be flexible with her time are some of the reasons Anja likes being in her host family arrangement.

For four weeks a year, Anja, Sarah, and David take a break from the host arrangement and Anja uses her short-term accommodation (STA) budget to stay elsewhere, perhaps with her family or with friends.

Sarah and David receive a subsidy for the expense of Anja living with them at $65,000 per year. The provider is responsible for ensuring the arrangement is working for Anja and Sarah and David, and will meet regularly with each of them, oversee the direct-care staff, and communicate regularly with Anja’s family.

*This is a fictional case study, for illustrative purposes.

2.1.3 Home-share

In this type of arrangement, an adult with disability lives in their own home (owned or rented) with a housemate who provides in-kind support in exchange for a subsidy for expenses, which often partially or wholly covers their rent.

Typically, where a housemate only receives free or reduced rent, they will provide less support than in a host family arrangement (up to 12 hours per week for a flatmate on top of passive overnight support), though this is open to negotiation.

As with host families, the preferences and needs of the person with disability and the housemate are laid out in a service agreement signed by all parties. Home sharers should enter into an agreement with only one person with disability, except in extraordinary circumstances, such as siblings who want to live together.

And as with a host arrangement, people with disability receive other kinds of support, including from paid support workers or through informal support, in addition to support from their home-sharer.

Box 2: Steven’s home-share arrangement

Steven* is 26 and has autism and needs help with problem solving, managing unfamiliar situations, and verbal communica- tion. He rents an apartment in Sydney with his flatmate, Jack. They’ve been living together for nearly a year, in a home-share arrangement that a registered provider helped them establish.

Steven works part time at a local supermarket, and Jack works full time as a landscaper. Steven usually works in the morning, and then goes out into the community with his support worker in the afternoon. Steven gets four hours per day of one-to-one support worker time with a team of support workers he has chosen.

Jack makes dinner for them both and Steven helps to stack the dishwasher and clean up. The routine that Jack and Steven have created helps Steven manage his anxiety.

Jack is home most nights in case Steven needs help, and when he’s not home, Steven can call his mum and dad or the overnight and emergency service if he needs help.

On the weekends, Jack and Steven like to go to the pub to watch the footy, and sometimes their friends join them.

Steven’s home and living package covers Jack’s rent as an acknowledgement of the household assistance, emotional support, companionship, and any emergency support required when Jack is home.

Steven wants to be independent, and he’s hoping to increase his work hours this year, either at the supermarket or at another job, or to study at TAFE.

*This is a fictional case study, for illustrative purposes.

2.2 Individualised Living Arrangements can be cost-effective

Individualised Living Arrangements can be cheaper than group homes because they tap into semi-formal support, instead of relying solely on rostered, paid support workers.

There are three kinds of support available to people with disability:

- Informal support is the kind of support provided by friends and family on a voluntary basis;

- Formal support is provided by professional support workers who are usually paid by the hour; and

- Semi-formal supports, which sit in the middle. These are services provided by people who want to provide support, but need to be subsidised for the costs associated with doing so.49

Semi-formal supports tend to be integrated into the life of the person providing support, and do not require the payment of an hourly salary.

While these arrangements can require more administration to set up, they tend to be less expensive than formal supports provided by workers paid by the hour.

Because the NDIS currently draws on only formal or informal support, people with disability and their families are frequently left with an ‘all or nothing’ approach: either a professional, paid-by-the-hour worker provides support, or it’s volunteered by family or friends.

The ‘all or nothing’ approach also means that some people are getting support they don’t need. In group homes, for example, residents share round-the-clock assistance from a support worker, at ratios ranging from one-to-three (using one-third of a support worker’s time) to one-to-one or higher in the most extreme cases.

The need for support is usually not exactly matched to the ratio of staffing provided. If a person with disability living in a group home needs support intermittently and unpredictably (for example, frequently at some times of the year and not others, or once a week on average but on different nights each week), then in practice it costs a similar amount to staff a support worker for this person as it does for a person who needs support every night – a worker is paid for an overnight shift whether the person needs their help or not.

Semi-formal support is a much more cost-effective way of giving people with disability the support they need, because it avoids the waste associated with a paid support worker whose labour is demanded only occasionally and yet supplied constantly. The semi-formal supporter lives their everyday life, and is available in case the person with disability needs them.

By adding semi-formal supports to the mix, Individualised Living Arrangements can be cheaper than group homes, which rely solely on formal support.

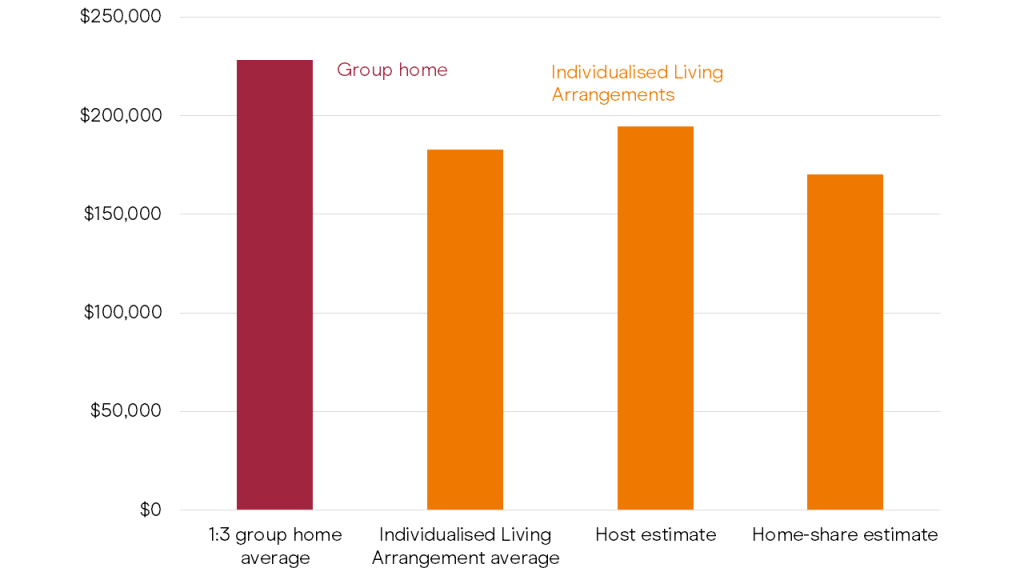

Grattan Institute analysis of data from Individualised Living Arrangement providers in Australia indicates that, on average, ILAs cost about

$183,000 per person per year, or about $45,000 less than a group home with supports shared at a ratio of one-to-three, which is the benchmark recommended by the Independent Review of the NDIS (Figure 2.3 on the following page).

Although a benchmark can help the National Disability Insurance Agency to centrally plan spending, a single one-to-three benchmark for housing and living support is unnecessarily restrictive. In Chapter 4 on page 36, we propose three funding bands that would cover the majority of people who need intensive housing and living support.

Anyone can call an Individualised Living Arrangement ‘home’, with the right match between the person with disability and their host or housemate. As people with disability transition away from group homes, it is likely that people who need passive overnight support will be the first to take up more innovative alternatives. Those who need active overnight support may need a support worker to stay in their home overnight. Even with this additional cost, it is possible that Individualised Living Arrangements could be more cost-effective than receiving round-the-clock formal support at a ratio of one-to-two or one-to-one (see Appendix B).

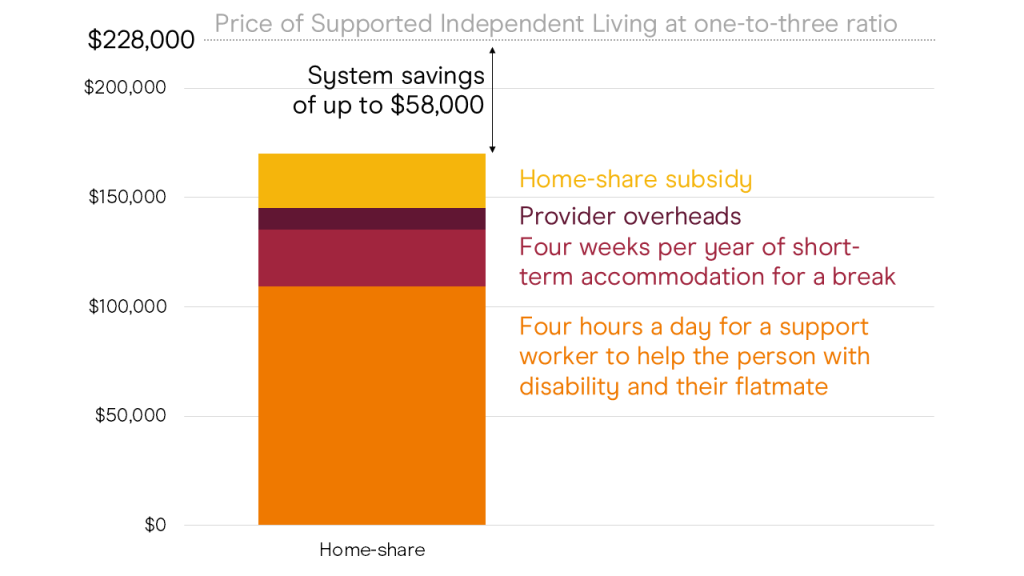

Figure 2.3: Individualised Living Arrangements cost less than group homes

Per person yearly cost of housing and living arrangements, 2024-25 dollars

Sources: NDIS Review (2023); Grattan analysis of unpublished provider data (2024).

Box 3: The flexibility in Individualised Living Arrangements creates savings

Sharing supports in a group home creates an economy of scale – three people can share one support worker, rather than living separately and needing one support worker each.

But sharing support workers also creates constraints. If one person goes to stay with their family for the weekend, the other two people still need rostered support workers. The cost is the same, even though fewer people are receiving a service. This means there are no savings to the NDIS from the person spending time with family and friends, rather than with support workers.

To save money, all three people with disability would need to stay with their families over the same weekend – a difficult coordination task.

Individualised Living Arrangements are more flexible than group homes. Informal and semi-formal supports are built into the service, instead of disabled people having to almost always rely on formal support.

2.2.1 Host arrangements can be cost-effective

Host arrangements can be cheaper than group homes, without the requirement for supports to be shared.

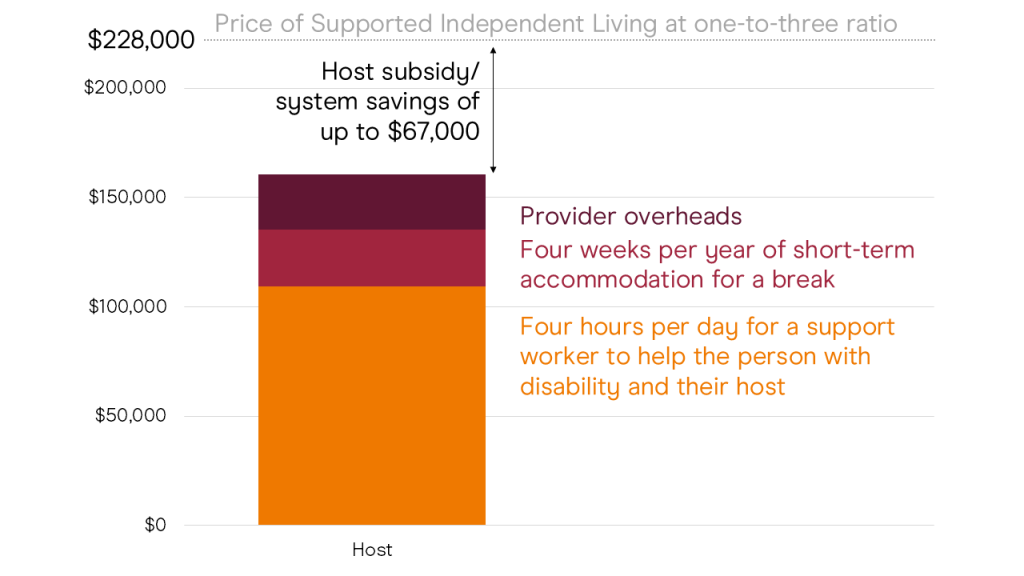

This is shown in Figure 2.4 on the following page where we compare costs against the NDIS Review benchmark of intensive living support funding set at one support worker for every three eligible people.50 The cost of providing living support for a resident in a one-to-three group home, with someone present overnight, is about $228,000 per person, per year (Figure 2.3 on the previous page).

A typical host arrangement might involve the person with disability receiving four hours of formal, paid support per day, costing about $109,000 per year. This support enables the host to work or engage in other social activities. People might use this time in different ways: some might prefer one or two days per week when they are not providing support; others might like help with particularly challenging parts of the daily routine.

Host agreements would also provide four weeks of short-term accommodation so that people with disability and their hosts can take a break, typical of NDIS arrangements where care is provided by non-professional workers. This would cost about $26,000 per year.

And providers would require some compensation (on top of the usual administration fees which are built into the price guide). A fee of 21.65 per cent for operational overheads, 12 per cent for corporate overheads, and a 2 per cent margin applied to the host subsidy to cover support with ongoing maintenance, review, and adjustment of the service, would cost about $25,000 per year.51

This would still leave more than $67,000 available to compensate hosts. It’s unlikely that hosts would require the full $67,000, and there is therefore considerable room to enable system savings.

Figure 2.4: Host arrangements can save money

Cost per year of innovative arrangements, 2024-25 dollars

Figure 2.5: Home-share arrangements can save money

Cost per year of innovative arrangements, 2024-25 dollars

Source: Grattan analysis of NDIA data.

2.2.2 Home-share can be cost effective

The usually lower support requirements of people in home-share arrangements provide even greater opportunity for savings.

We recommend similar short-term accommodation and daily support for disabled people in home-share arrangements as in host arrangements. And providers compensation of 21.65 per cent for operational overheads, 12 per cent for corporate overheads, and a 2 per cent margin applied to the flatmate’s subsidy to cover support with ongoing maintenance, review, and adjustment of the service, would cost about $9,700 per year.

A subsidy of $25,000 for the flatmate providing support would still enable a system saving of $58,000 per year, as shown in Figure 2.5 on the preceding page, though this saving would be lower in instances where the agreed level of support is higher, attracting a higher subsidy.52

2.3 Individualised Living Arrangements promote genuine choice for people with disability

Individualised Living Arrangements provide another option for people with a disability, away from the old system of group homes.

Although the NDIS seeks to promote choice and control for people with disability, merely promoting choice without creating options is a meaningless exercise. Currently, people with intensive needs often have few choices when it comes to their housing and living supports;

which house they live in, who their housemates are, who provides them with support, who helps them get in and out of the shower, or what they eat and when.

Stimulating growth in Individualised Living Arrangements promotes choice at two levels, first by expanding the number of service options and providers available to people with intensive support needs,53 and second by improving the choices they can make within the service, over where they live and who they live with, as well as who provides support and how.

These kinds of choices are a central focus of the planning and design of Individualised Living Arrangements.54

This matters because research indicates that people with disability who choose their services, supports, and who they live with, tend to have better quality of life.55

Choosing who provides your services matters too. People who need intensive living supports are in frequent, close contact with their support workers. If you need help getting in and out of the shower or bed, getting dressed, or using the bathroom, who helps you is a decision you want control over. The way in which support is provided is just as important as what is provided.56

For disabled people living in rural or remote areas, having the option to live with a host, or rent a property in the private market in a home-share arrangement, could be the difference between living in your community, and having to move to get the services you need.

2.4 Safeguarding Individualised Living Arrangements

Individualised Living Arrangements with appropriate safeguards also offer the potential to improve the safety of people living with disability.

ILAs tend to have an explicit focus on building people’s independence, and expanding their social networks. Building these natural networks of support can be a crucial factor in ensuring participation in the community and keeping people safe.57

However, there are clearly risks to a person with disability living with another family in their home, or with flatmates. The risk of exploitation58 means that the design of ILAs is important, particularly to ensure that there are a range of supports in the package and the disabled person has regular contact with multiple people, rather than relying solely on their host or flatmate.

Individualised Living Arrangements should usually be overseen by a registered provider who can step in when needed. There should also be external oversight and check-ins, to make sure the person with disability is safe and happy.

There should always be formal support in host arrangements, as well as informal support where possible, so that the person with disability is receiving support from a variety of people and not only the host. The registered provider overseeing the host or home-share arrangement can hire staff directly, because they do not own the property in Individualised Living Arrangements.

Hosts and flatmates are not employees, so there is no need for them to register. However, the provider managing the arrangement should be registered, and they must have up-to-date information about hosts or flatmates. Registered providers should require hosts and flatmates to complete a worker screening check.

If the person with disability is self-directing their supports, then they should register themselves so that their support providers, including hosts or flatmates as semi-formal supports, are visible, as recommended by the NDIS Provider and Worker Registration Taskforce.59 Capacity-building for people who are self-directing their supports should prioritise those with Individualised Living Arrangements.60

Hosts and flatmates should not have power over disabled people’s plan funding, or any other role in their plans. Semi-formal supporters need explicit training that should be outlined in the practice standards for Individualised Living Arrangements, and access to capacity-building support (see Chapter 4).

2.5 Three policy settings to enable Individualised Living Arrangements

So far in this chapter, we’ve shown that creating alternative options for people with intensive housing and living support needs is possible, desirable, and can be cost-effective. Three changes to current policy settings would ensure these options are more widely available to people.

2.5.1 Make hosts and housemates volunteers, not employees

The types of Individualised Living Arrangements we have described are possible under current legislation, so long as specific rules are applied.61

Most importantly, the role of hosts and housemates (and any other semi-formal supporters that might form part of a person’s ILA) must be established as volunteers, not employees. This should be clearly reflected in service agreements.

In these roles, hosts and housemates receive a subsidy for expenses associated with a person with disability living with them. These expenses cannot include items that the NDIS does not cover, such as food, utilities, or the person with disability’s rent (which typically come out of the person’s Disability Support Pension and Commonwealth Rent Assistance).

Expenses might include those associated with the disabled person staying connected to the community, maintaining or building relationships, travel, and more. Within these parameters, subsidies are not subject to income tax, and are excluded from social security income calculations.

We estimate that the subsidy would be similar to the foster care system, with two differences; firstly, foster carers are reimbursed for everyday living expenses, while hosts are not, and secondly, the proposed subsidy acknowledges that people with disability face increased living costs on account of their disability.62

Therefore, we estimate that hosts could be subsidised between $50,000 and $80,000 per year, pegged to the consumer price index and dependent on the costs the host incurs.63

The Agency should produce guidance about the rules for providers and people interested in establishing an Individualised Living Arrangement, so that they are implemented faithfully.

2.5.2 Establish a rental payment to encourage innovation

Transitioning away from group homes and into more innovative options will not succeed if people in the program cannot afford rent. And unstable housing on the private rental market will make it challenging for people in the program to establish long-running care arrangements, essential to any innovative arrangement’s success.

To increase stability for people in innovative housing arrangements, we recommend that the NDIA provide a targeted rental payment to people with intensive living support needs as an alternative to group homes. We outline the details of this payment in Section 3.3 on page 34.

2.5.3 Allow people to keep unspent funds to spend on other services

Based on our analysis, Individualised Living Arrangements often will cost less than group homes and other arrangements that use only formal support. Some people may want to take up more expensive options, because they think the higher price means greater quality, or that the NDIA will take away their funds if they don’t spend every cent. This thinking might lead people to make choices that aren’t in their best interests (or in the best interests of taxpayers).

As an incentive to take up less expensive Individualised Living Arrangements, people in the NDIS should be allowed to keep unspent funds from their home and living budget for an agreed time limit (for example, up to a year). Allowing people with disability to keep unspent funds takes the pressure off them to spend as much as they can, and better aligns their interests with those of the taxpayer. If people with disability do not spend all of these excess funds, there are potential savings to the NDIS and in turn, taxpayers.

People should be able to transfer excess funds from their home and living budget into their general budget to use on other services, such as therapies, capacity building, or community participation. If their home and living supports cost consistently less than the projected cost, the NDIA should consider shifting down their home and living budget in increments, so long as the person’s circumstances have not changed. If home and living budgets are consistently lower, then the NDIA should adjust plan funding benchmarks (see Chapter 4).

Chapter 3: Reform the existing system

Even as more people take the opportunity to move away from group homes, there will still be some who choose to live together and share support. Reform is needed across the system so that the NDIS can fulfil its duty to every person with intensive housing and support needs, regardless of their living arrangement.

Where disabled people make the choice to live with other people who have a disability, it should be in an environment where they retain control over how they live their lives. People with intensive support needs should be able to choose who they live with, who provides their support, and how. The rhythm of their day should be a choice, not something dictated by government or service providers.

These changes should be rolled out as soon as possible to ensure that institutional care does not continue.

The transition away from the institutional-style bricks and mortar of some group homes will take longer. These homes should be replaced over the next 15 years.

3.1 From group homes to share houses

Group homes were favoured when disability care was de- institutionalised, because multiple co-residents enabled providers to share support worker time. But the more people who live in a given house, the more difficult it is to create a home-like environment. The largest group homes, sometimes called ‘legacy stock’, can have six or more residents and are particularly common in Victoria.64

But the presence of group homes in disability care is not inevitable. Western Australia for instance, has pioneered alternative arrange- ments, meaning fewer people need to live in group homes (Section 2.1.1 on page 18).

The Disability Royal Commission called for group homes to be phased out within 15 years, due to poor safety and quality, namely:

- high rates of violence, abuse, neglect, and exploitation in group homes;

- the tendency for residents to be segregated from the community, spending much of their time with paid staff rather than friends, family, and community members.65

Group homes in their current form clearly need to change, but like many Australians who live with their peers in share houses, some disabled people will probably always choose to live with other people with disability. Some people report increased loneliness after moving from group homes to live by themselves, and there is nothing inherently wrong with people deciding they would rather live with other people.66

The NDIS needs a practical plan to enable people with disability to live with other disabled people while maintaining control of their daily life. But to achieve choice within shared living, there needs to be a re-imagining of what a home-like environment is, rather than merely tinkering with the number of people in a house.

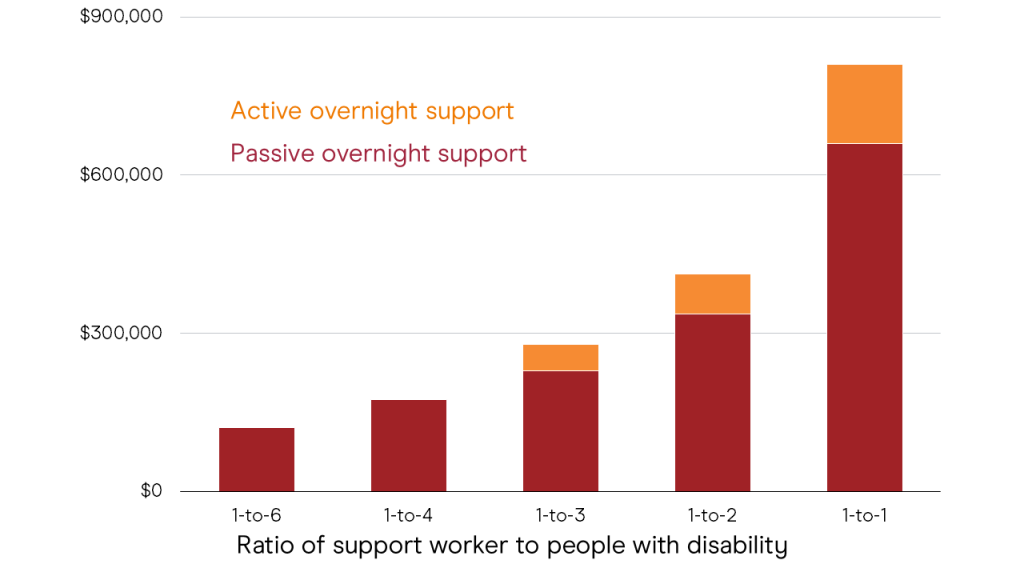

The NDIS Review grappled with the trade-off between economic efficiency and providing a home-like environment and recommended a benchmark ratio of one support worker for every three supported residents.67 Some advocated to the review for expanded one-to-one funding of support workers,68 but this would be financially impractical for the scheme.

Economy of scale is not the only way to provide cost-effective support, as Chapter 2 shows. However, it can help to reduce cost where people use only formal support. Costs increase dramatically as the number of residents in a group home falls (Figure 3.1). One-to-one care is

$419,000 more expensive per year per resident than one-to-three care. If that extra money was spent for every person eligible for Supported Independent Living funding, it could cost the scheme up to $14 billion extra per year.

Better still, a growing feature of share-houses could be sharing both formal and semi-formal support. Combining the economy of scale from sharing support workers, with semi-formal support from a housemate, would be a cost-effective way to run share-houses in the future.

The most important difference between a group home and a share house is the level of choice and agency that people have over their day-to-day lives.

Residents should be able to control who they live with, who looks after them, and how. Changing the power-dynamic between providers and residents requires changes to the layout of group homes, the way decisions are made, and how those decisions are enforced.

Many of these changes can be achieved by improving the way support is provided by staff, but some improvements require other structural changes to the way services and residents interact.

Figure 3.1: Shared supports are much cheaper than one-to-one support

Yearly cost for each person with a Supported Independent Living plan, 2024- 25 dollars

Source: NDIS Review (2023a, p. 548).

3.1.1 Providers need to deliver ‘Active Support’

The biggest factor in determining the quality of supports in shared accommodation is the quality of the staff and organisational supports.69 A prominent way of describing high-quality care is ‘Active Support’, which has been shown to increase engagement in activities for residents in shared accommodation.70 Active Support involves:

- Workers using opportunity to engage with the people they support.

- Workers providing ‘graded assistance’ – just enough so that the person is supported and can develop their own skills.

- Maximising residents’ choice and control.

- Support being provided in frequent, short periods of engagement, to maximise concentration and opportunities for success.

Active Support can be measured in an organisation through surveys that rank support-worker and management adherence to practices that maximise residents’ quality of life. Active Support works best when

the leadership and culture of the organisation continually reinforce it through training and rewarding good practice.71

Training resources developed by people with disability themselves which effectively communicate their needs and preferences to support workers can also improve the way support is provided.72

3.1.2 Residents should make collective decisions about how the household is run

Residents need to have more control over how decisions are made that affect their lives. Resident-led governance means giving share-house residents control over who lives in the house, who the workers are, and the everyday rhythms of the house such as meal-times and outings.

Some residents of group homes have already achieved greater control through resident-led governance, but this is usually only possible with the help of family members who advocate on behalf of their loved ones.73

The NDIS Review mentions Supportive Independent Living Co-operatives, where friends and family of group-home residents employ a ‘housing operator’ that performs all the roles of a registered provider, but with clear lines of governance with the family at the top.74

Another innovative arrangement for resident-led governance is the concept of micro-boards, where members of the community including family and others form a formal support network around a person with a disability.75

While these innovations show promise, residents without family to advocate for them too often end up living their day-to-day lives at the convenience of service providers rather than according to their preferences.

The NDIS Review outlined a series of reforms to overcome this problem, starting with a recommendation to create a new role of shared support facilitators who would act as an intermediary between service providers and residents to advocate for residents’ choices.76

In Chapter 4 on page 36 we advocate for the new role of local housing and living support navigators. One of the functions of this role would be to connect share-house residents with a range of other supports, including support for decision making, micro-boards, advocacy or other capacity building supports, many of which we recommend are directly commissioned by the NDIA.

By employing local navigators who have better knowledge of other options in the local area, the NDIS could also increase the chances that people who are not happy with their current housing situation can find either new housemates and/or a new home.

We don’t think it makes sense for there to be a separate role in the system solely focused on shared support facilitation. It is better for navigators to work with the disabled people they support and connect them to the other supports they need to have control over decisions in the home, all the way from package creation to household mediation and moving house when needed.

3.1.3 Make service agreements enforceable

If disabled people are going to have more control over how care is delivered in shared accommodation, the NDIA needs to help facilitate better agreements between providers and share-house residents.

Currently, the NDIA recommends that all service providers and people they support draft their own service agreements which set out the terms agreed between them. These agreements typically include broad motherhood statements about how all people using the service should be treated with respect, but do not include enough detail to enable residents to negotiate how they spend their everyday lives.

Service agreements should instead be mandatory and include detailed information about how the person with a disability wants to live their life. It should include information about the daily rhythm of the household, as well as how new workers and housemates will be chosen, inducted, or dismissed. The NDIA should provide a standard template to facilitate discussions between disabled people and providers.

These agreements also need to be easily enforceable. Currently, people on the NDIS are directed towards the consumer law regulator to deal with any disputes that might occur as a result of contract disagreements.77 But this regulator is not properly situated to mediate household disputes.

The NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission should provide a mediation service to facilitate agreement where providers or people using their services feel their service agreement is not being upheld.

After a grace period of 18 months, the new service agreements should be a requirement of all NDIS housing and living support provider registrations.

3.1.4 Separate living and housing supports

For many people who live in group homes, their house and support is currently provided by the same organisation. Real choice in housing and support can’t be achieved where the provider of housing is also the provider of living support. This can mean people’s home is at risk if they want to change who provides support. Consequently, both the Disability Royal Commission and the NDIS Review recommended the separation of housing and living support.78

Separating the provision of housing and living supports would give people more freedom to choose their support workers.

As group homes are phased out, and more people move into other housing, the NDIS should mandate that by default, all new housing is provided by a different operator to the one providing living supports.

Over time, existing operators that provide integrated services should be phased out. After a grace period of 18 months, all providers should need as part of their registration process to demonstrate that they have moved away from integrated living and housing supports.

These operators should be given time to make the transition, because they might choose to exit the market if the transition is too sudden.

For some services, integration might make sense, for instance where a short-term service is introducing positive behaviour support to address behaviours of concern, or in the case of host arrangements where hosts provide some living support and housing for the person with disability, alongside formal support from workers. These services should be able to apply for an exemption to the requirement of separation between housing and living. These integrated arrangements should be reviewed every five years, or earlier if requested by residents, to manage conflicts of interest, ensure that a high-quality service is being provided, and check that intended results for residents are being achieved.

3.1.5 Fund providers so there is time for vacancies

Just like people who live in any share house, people with disability need to be happy with the people they live with. But the job of finding the right person to move in with can be a lot more challenging for people with intensive support needs.

Where the intention is to share supports, there are only a small number of people eligible for these services, and the average tenure of people in group homes or specialist housing is much longer than in the typical rental market. As a result, finding the right person to fill a vacancy can take time.

Specialist Disability Accommodation rules reflect the challenges that can be faced finding a new tenant, but there is no such help for providers of intensive in-home supports.

An SDA provider will get paid for between 60 and 90 days where there is a single vacancy in a multi-person dwelling.79 But only four weeks leeway is granted to support providers when there is a vacancy in

their service roster.80 As a result, people in group homes are either not properly consulted on their new housemate or are pressured to accept a new resident who is not the best fit.

The NDIS should fund both SDA and in-home support providers in multi-person living situations for vacancies for up to 60 days, to enable the remaining residents to find the right housemate to join their share house. Service agreements should set out protocols for how residents can lead decision making when filling a vacancy in their home.

After 60 days, providers should be able to apply for extra funding and more time, provided they can demonstrate that significant effort has been made to find a new housemate, for instance by interviewing potential candidates.

These vacancy payments would add some costs to share-house administration, but these costs should be offset by greater stability in housing arrangements, fewer disagreements between residents, and fewer complaints and reportable incidents.

3.2 End legacy stock within 5 years

As more people transition away from group homes, there needs to be a timeline to completely close any houses that have an institutional-like architecture. While some group-home stock may be able to provide share-house like environments, other homes (particularly legacy stock) are far too institutional to make the switch.

As a first step, no new institutional-like buildings should be built. But replacing existing stock will take time. Given only 825 new-build Specialist Disability Accommodation dwellings were enrolled in 2021-22, Australia’s unsuitable group homes cannot be replaced overnight. For legacy stock (with 6 bedrooms or more) a timeline of 5 years is enough to transition to more suitable dwellings. For group homes with 4 and 5 bedrooms a timeline of 15 years is more than enough to ensure housing demand is met for existing population growth, while transitioning to more suitable accommodation. This timeline also recognises the challenges faced by existing residents who may not want to move home.

By 2040, no Australian should be living in a group home unless they have been given reasonable opportunities to choose to leave their existing house and chosen not to do so.

3.3 Don’t use Specialist Disability Accommodation housing to entrench the group-home system

When people with intensive needs require highly specialised housing, they become eligible for Specialist Disability Accommodation funding to account for the extra cost of providing their home. People that entered the NDIS in group homes previously run by the States all automatically qualify for SDA as well.

Over the coming decade, a significant expansion of new SDA housing is expected as more people are transferred out of ageing housing stock.

But not everybody with intensive in-home support needs currently qualifies for SDA. Some people are not eligible because they don’t require a highly specialised home.

Finding an appropriate place to live is difficult for all Australian renters. Rents are up nearly 12 per cent since the start of 2022. They rose 7.3 per cent in the last year alone. To make rent more affordable, Grattan has previously recommended at least a 40 per cent increase in Commonwealth Rent Assistance.81

But people who receive intensive living support face extra difficulties not faced by other renters in the private rental market.

Many of these people are living in non-SDA group homes, boarding houses, or Supported Residential Services. The NDIS Review heard that many of these people are currently targeted by unscrupulous provider-landlords because of their large support packages.82 The NDIA has no visibility of these arrangements, and the regulator is oblivious to their quality.

Rent is not currently paid by the NDIS, and this group’s only way to pay rent is typically with the Disability Support Pension and Commonwealth Rent Assistance. And moving house can be particularly socially dislocating for people who need intense housing and living support.

If they need to move to an area where there is cheaper rent, doing so will often result in the loss of the informal support of family and friends, and the gap needs to be made up with much more expensive formal supports.

Where people with intensive support needs are not eligible for one of the current Specialist Disability Accommodation categories, or wish to move away from their group home, they should instead get a housing payment that can be used in the private rental market.83 This could be spent on a new lease, or be paid to the current housing provider where people are content with their living situation.

This payment would encourage longer rental agreements and reduce the geographical dislocation that can happen when rents go up in a given city.

The rental payment should be set at a level which:

- Ensures that a person would not need to spend more than 25 per cent of their Disability Support Pension plus 100 per cent of their Commonwealth Rent Assistance to pay for their share of the median asking rent in their region.84

- Compensates landlords for costs associated with their registration and ongoing engagement with the regulator.

- Covers the cost of additional tenancy security (e.g. minimum terms of two years).

- Reflects the landlord’s agreement to permit minor household modifications that bring the property in line with housing standards for new builds in the area.

Just like rent assistance, ideally this payment should be provided directly to the person enrolled in the NDIS.85

To receive the payment, the person who needs living and housing support should need to register their rental agreement with the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission. Registration would ensure that the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission can keep track of when there is more than one participant registered at an address, which could trigger an audit of quality and safety.

This recommendation differs from the NDIS Review recommendation to create a new Specialist Disability Accommodation category for people with intensive living supports who do not currently quality for SDA, to enable the review’s preferred one-to-three staff to residents ratio.86

A specific class of SDA housing that’s effectively designed to create new group homes risks entrenching the existing system for another generation.

Allocating this money to a fully portable stream would ensure it is not tied to a designated class of disability housing, and would increase the prospects of people with intensive needs living in ordinary homes in the community with Individualised Living Arrangements.

The cost of this payment is likely to be about $12,800 per person, or $187 million per year across all 14,600 people who currently receive Supported Independent Living but not Specialist Disability Accommodation.87 While the NDIS Review did not cost the alternative of a new Specialist Disability Accommodation payment, the lowest existing payment for a newly built group home is $53,772, and so even a greatly reduced reimbursement amount would cost the same or more than our proposal.88

Chapter 4: Improve planning and coordination

For disabled people to get better results from a wider range of housing and support options, they must have the time, help, and flexibility they need to plan their supports and navigate the system.

The way these processes currently work falls well short of what is needed, and the NDIA has not done enough to encourage innovation or to support people to make well-informed choices.

In the previous two chapters we outlined the alternative options that should be available and how existing services should be reformed. In this chapter we describe how planning, budget setting, and service coordination should work so that people who need intensive housing and living supports get more certainty, consistency, and specialist help from the NDIS.

The NDIS market also needs more help from government so that providers can step up to supporting people in new and different ways. The National Disability Insurance Agency must adopt a more proactive and strategic approach to stewarding the disability market, including by intervening directly to commission vital services, accelerate innovation, and support promising new approaches.

4.1 People don’t get enough help planning their housing and living supports

If you or a loved one needs housing and living support from the NDIS, you’re in for a bureaucratic nightmare. There is no dedicated pathway to these supports. That makes it difficult for people to navigate their way through the system, which often they have to do in a crisis.

Currently, the first step is to amass a raft of assessments and allied health reports showing how much support you need and how often.

Your documents are sent to the NDIS which centrally processes your application, usually without ever meeting you in person.

The NDIS is supposed to support people through this process, but actual guidance is limited. The NDIA contracts Local Area Coordinators to provide a few hours of (usually in-person) advice, but people frequently need to do a lot of legwork on their own.