Overview

Elections are our opportunity to set Australia’s path. This report charts the path to a more prosperous Australia: the policies that should be on the agenda of whoever wins the 2025 federal election.

This election is being held at a time of great uncertainty. The international rules-based order is under siege, and the world is more unstable than it has been in decades. The impacts of climate change are showing themselves. Many Australians, having only recently emerged from a global pandemic, have faced significant financial pressures from rising living costs. But Australia has successfully navigated the crises of recent years while avoiding mass job losses and bankruptcies.

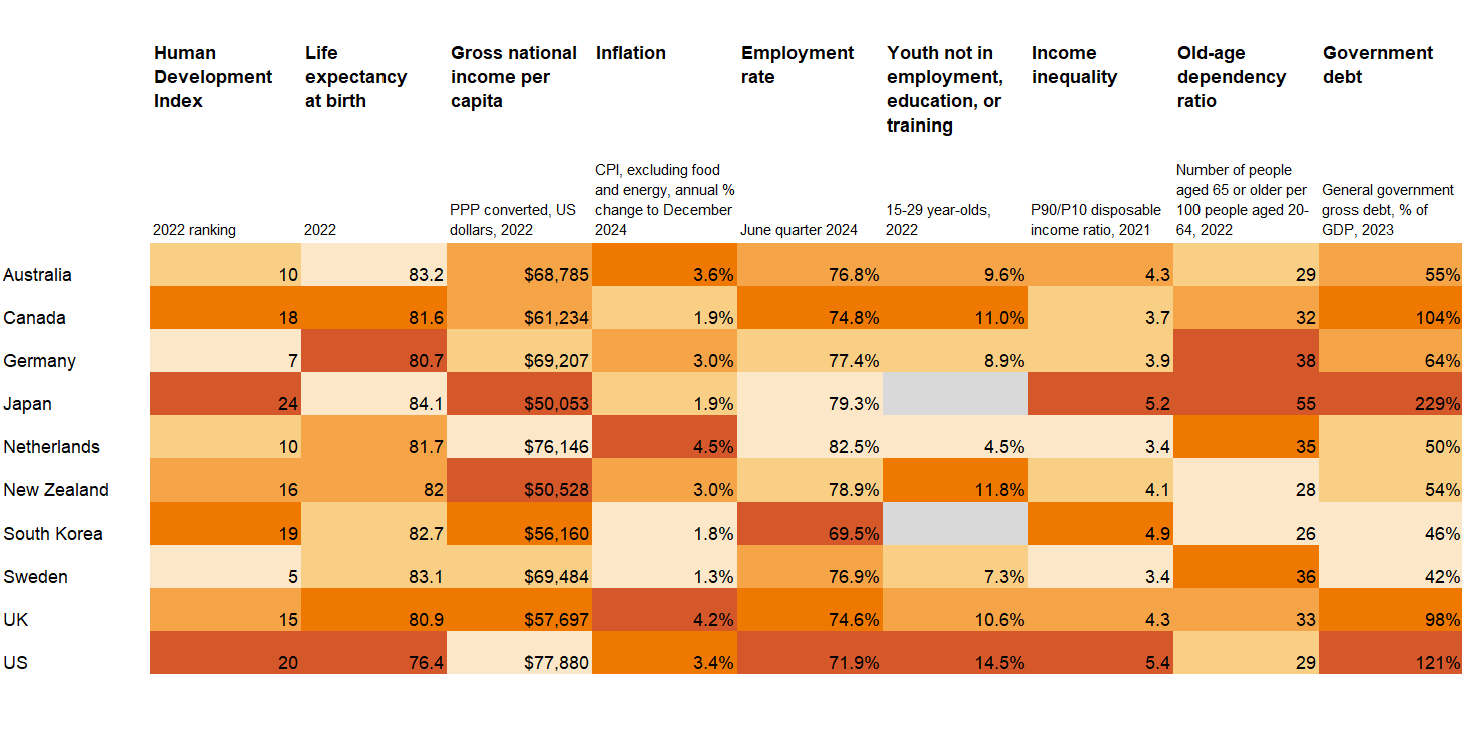

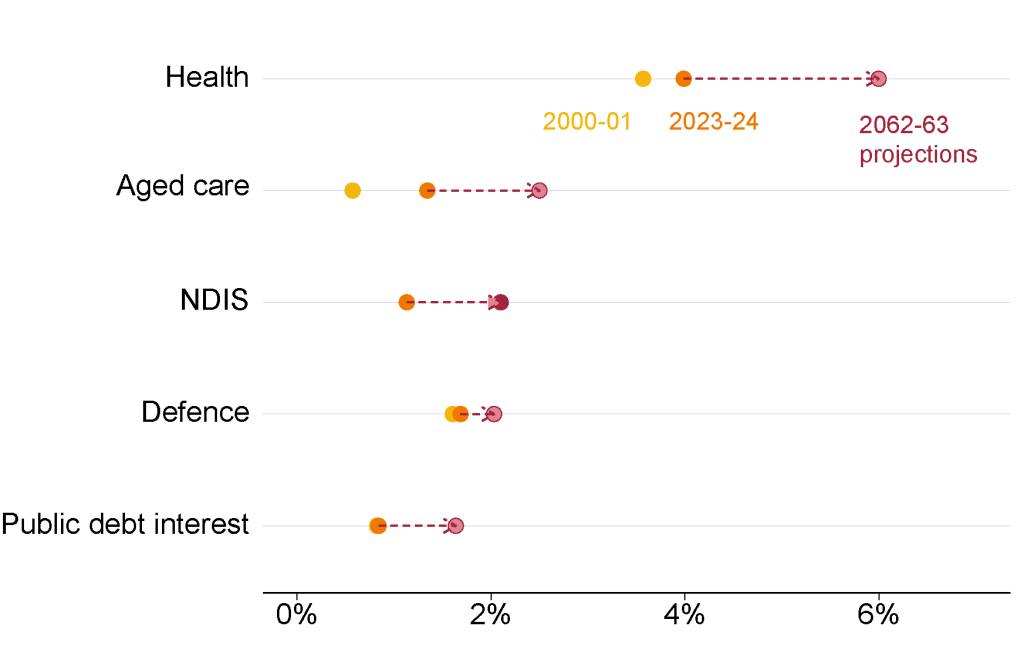

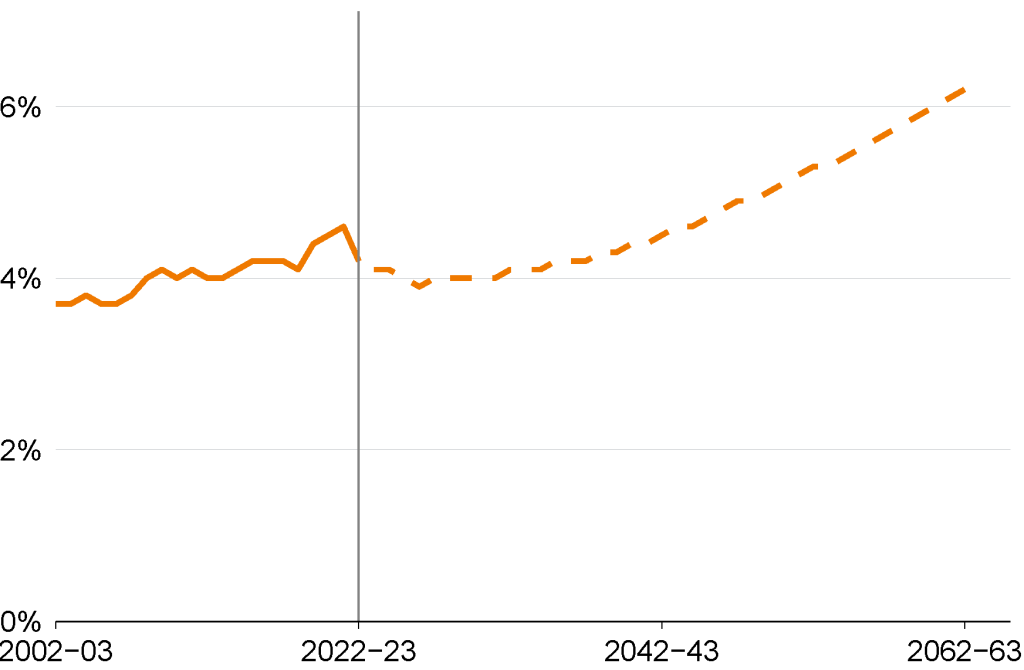

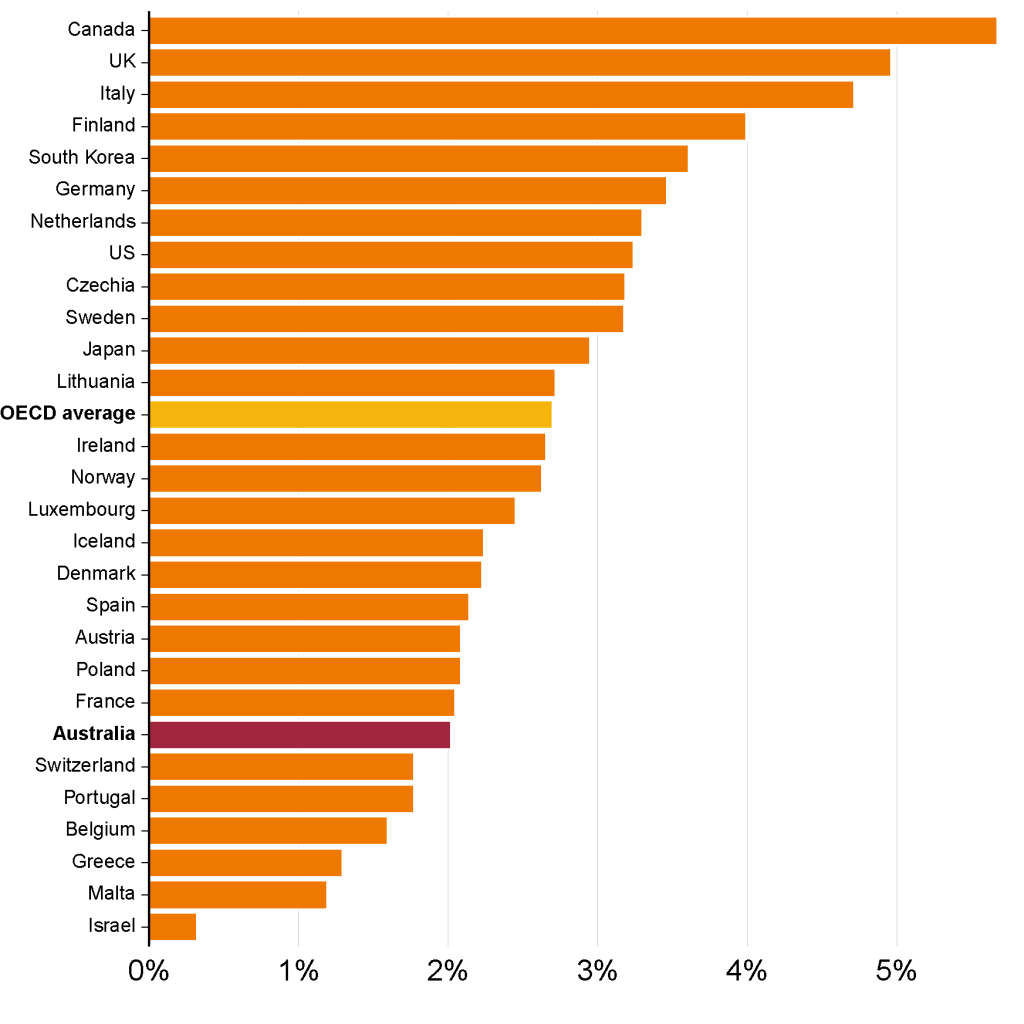

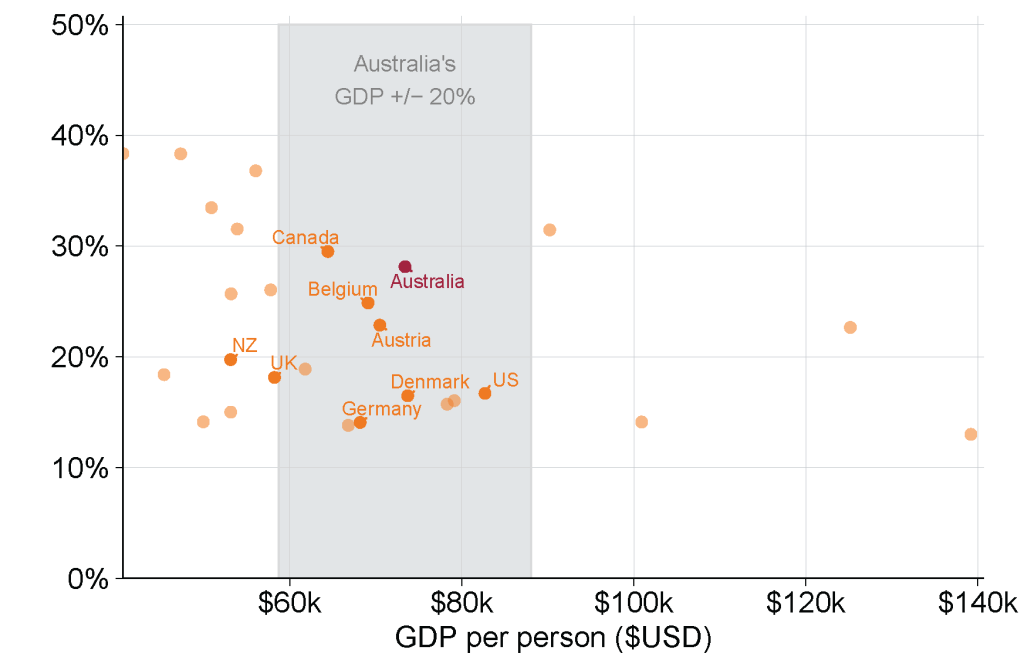

With inflation having fallen, it is our long-standing challenges that await: an ageing population, growing demand for health and care, a housing system that doesn’t serve our most basic needs, weak productivity growth, and the urgent imperative to decarbonise our economy. These are challenges we share with many other countries – and Australia is better placed than most to meet them.

This report offers a policy blueprint to improve living standards for all Australians, now and in the future. Fortunately, Australia is not starting from scratch – progress is being made on several fronts, but governments will need to stay the course on necessary but difficult reforms, and tackle others left in the too-hard basket for too long.

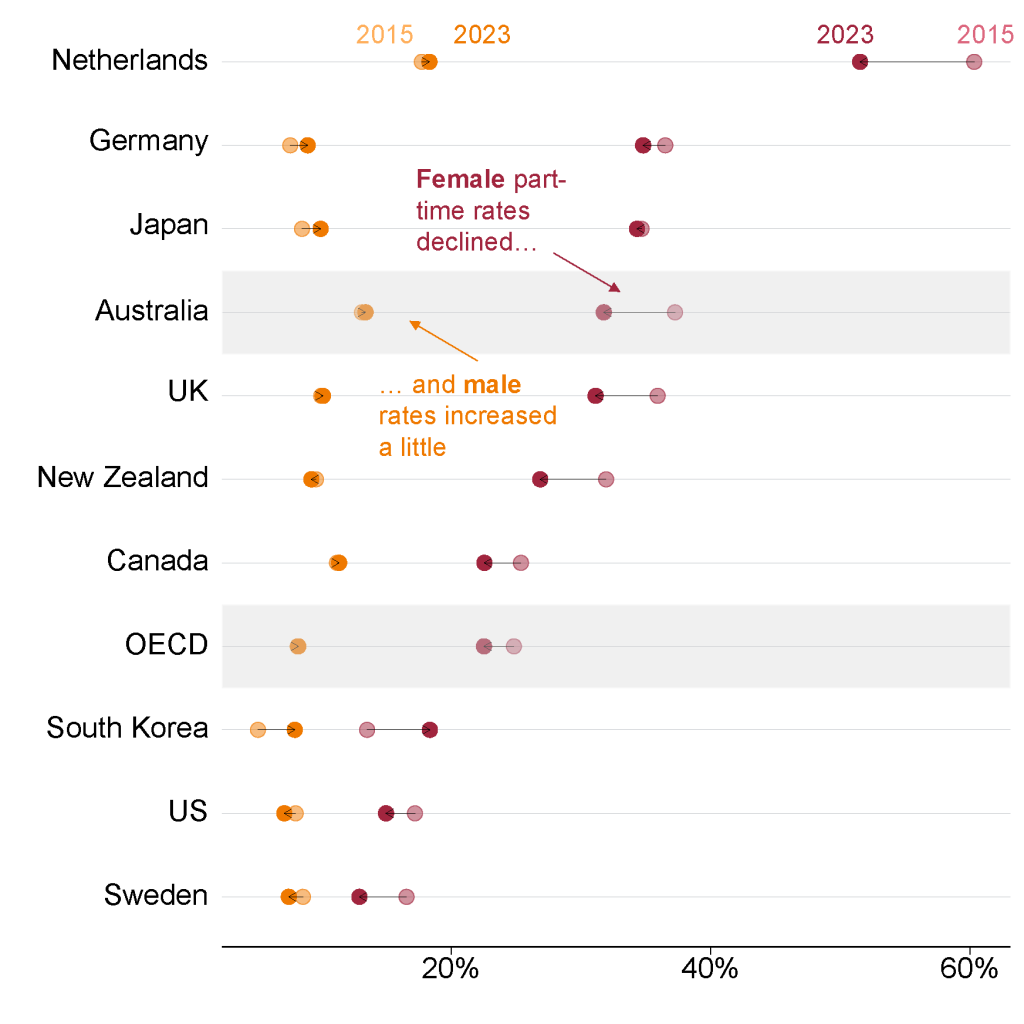

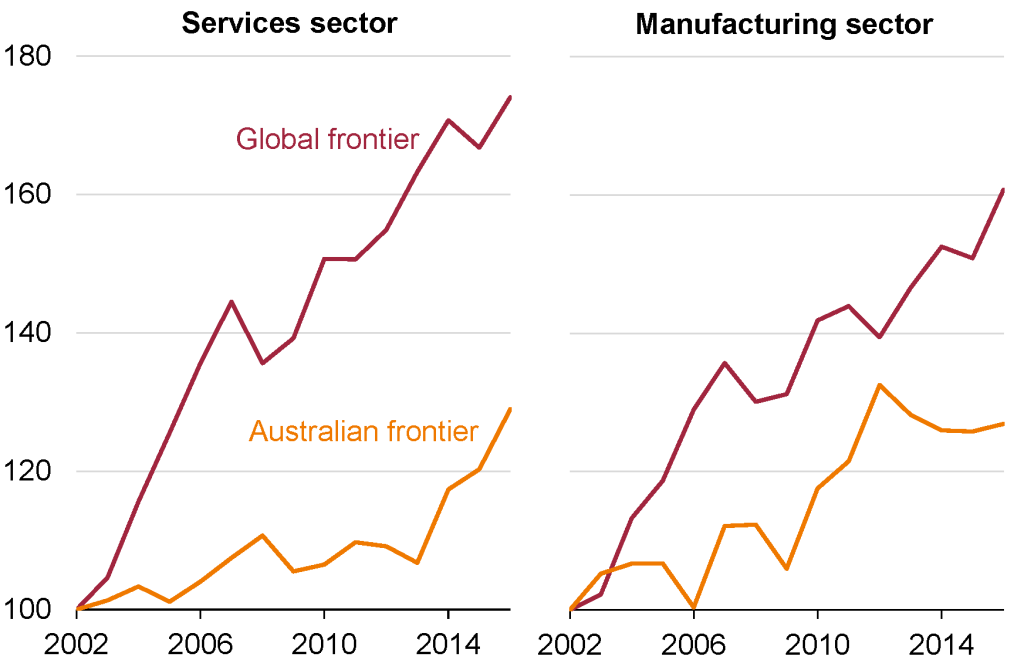

Productivity growth is the key to raising our living standards in the long term. While the federal government doesn’t hold all the levers, it can strengthen the foundations: a competitive economy, a well-functioning labour market, the conditions for people to flourish (housing, health, education, and social cohesion), and the right infrastructure, tax, and regulatory settings.

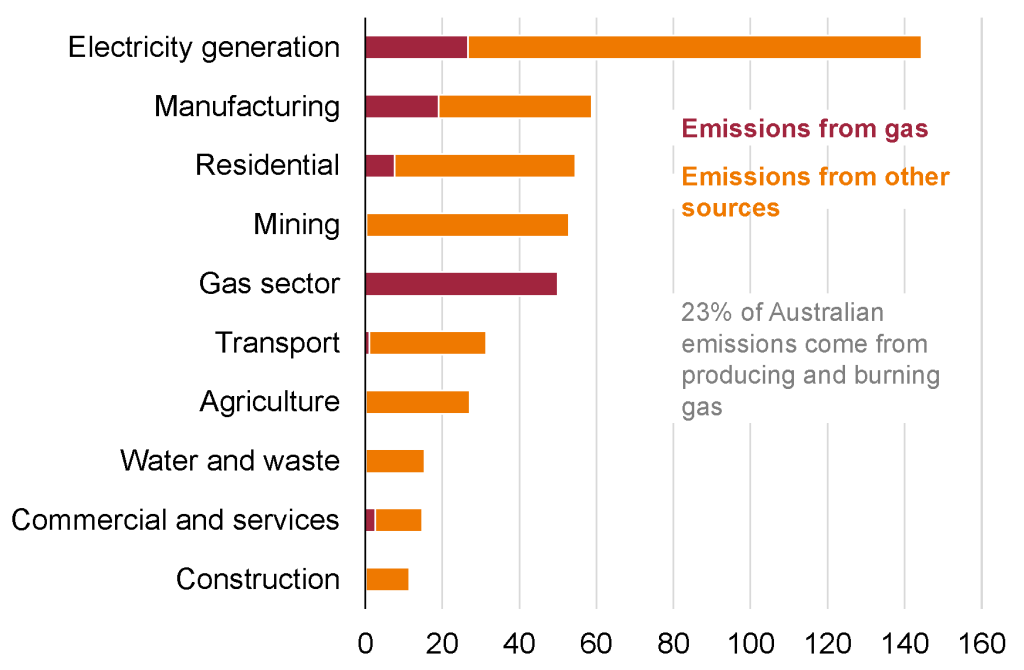

The transition to net zero presents opportunities for new high-value industries that use renewable energy. Implementing electricity and gas market reforms and comprehensive industry policy will be essential to realising them and avoiding a disruptive and costly transition later.

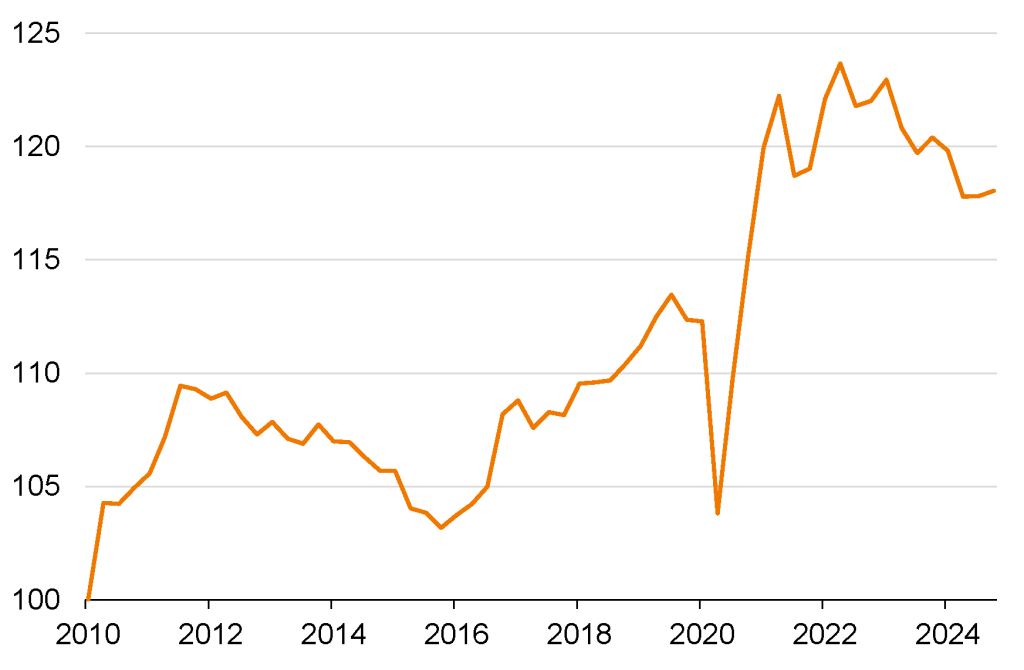

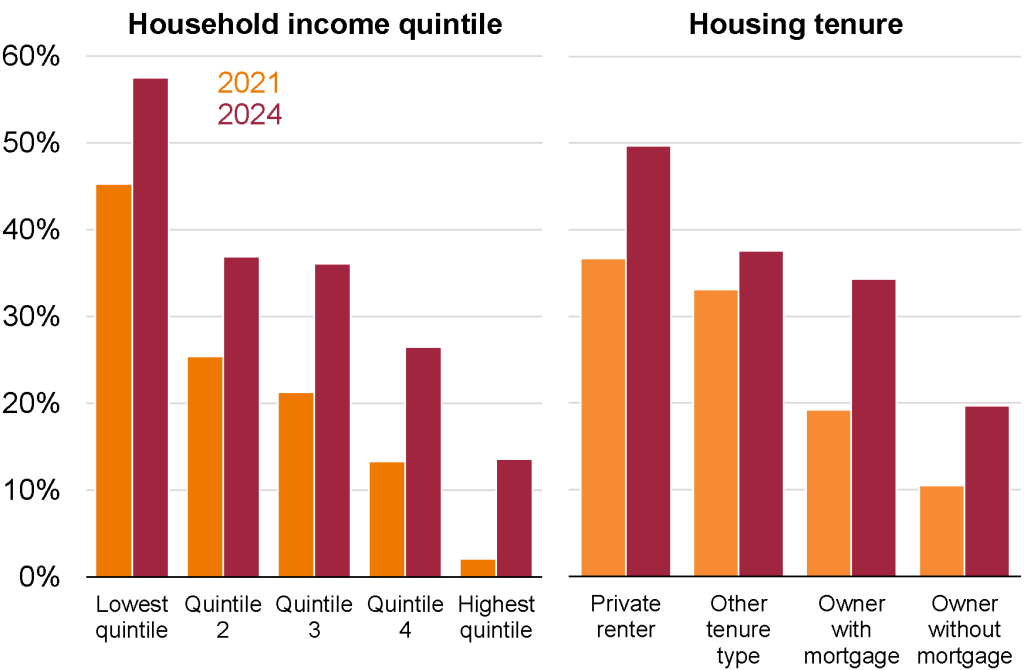

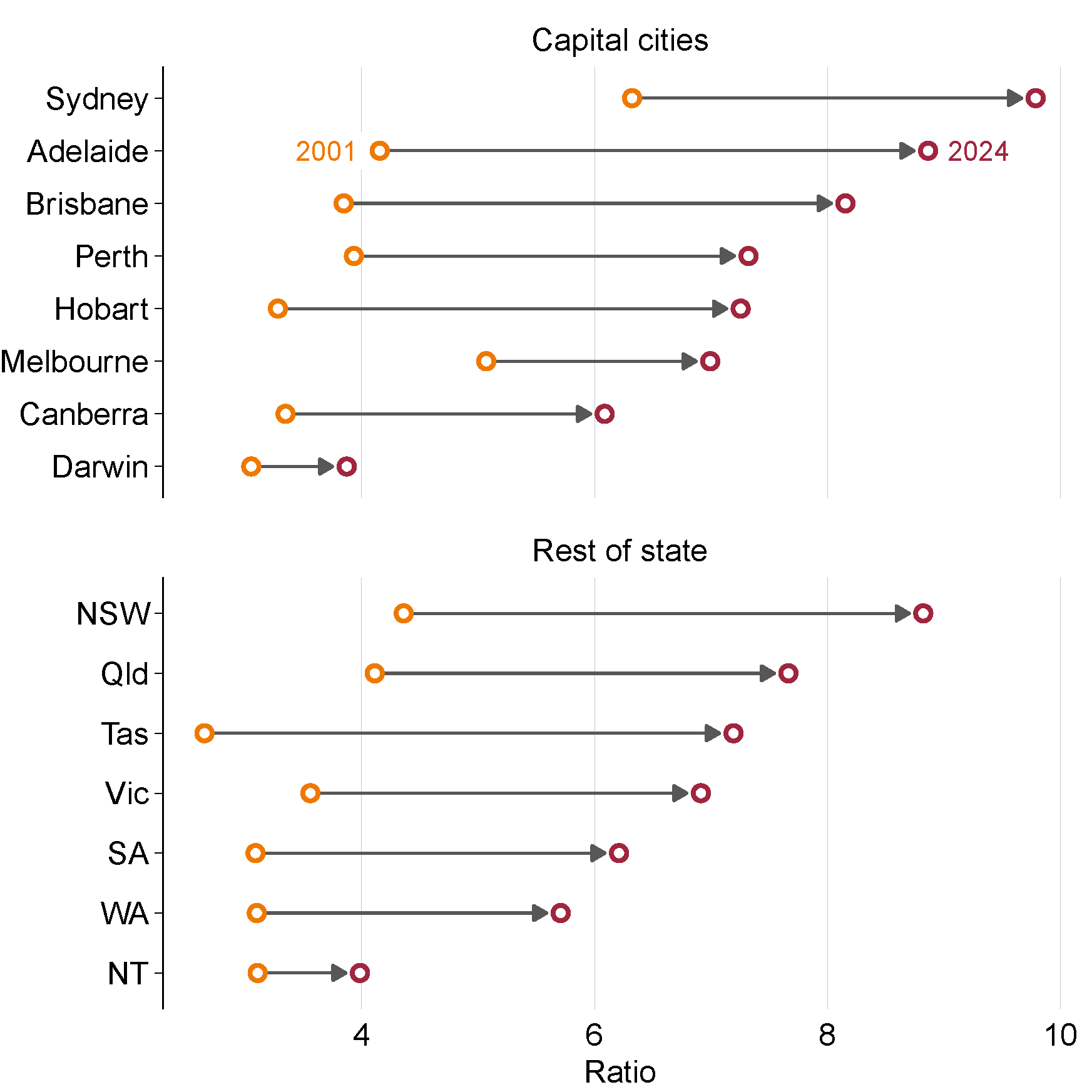

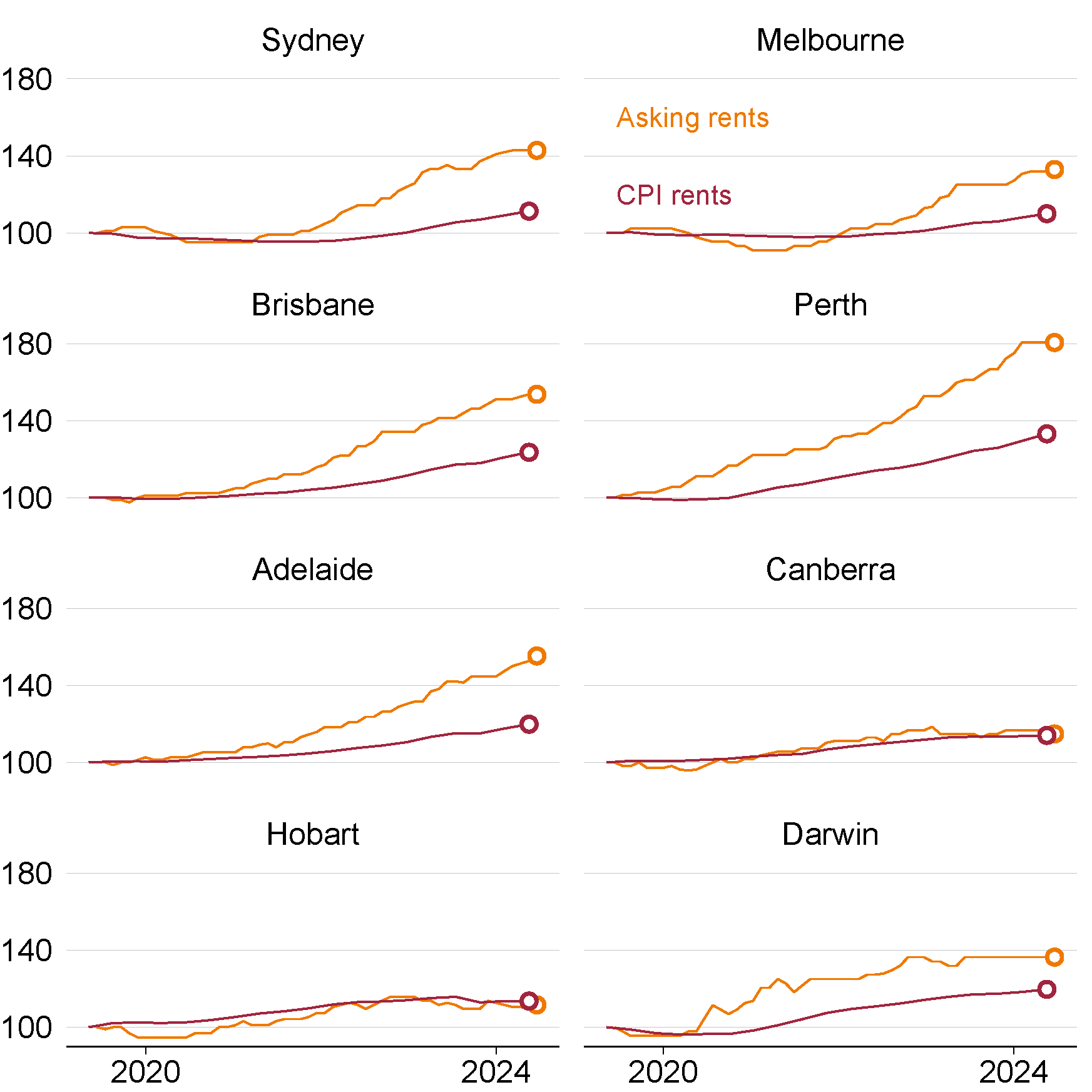

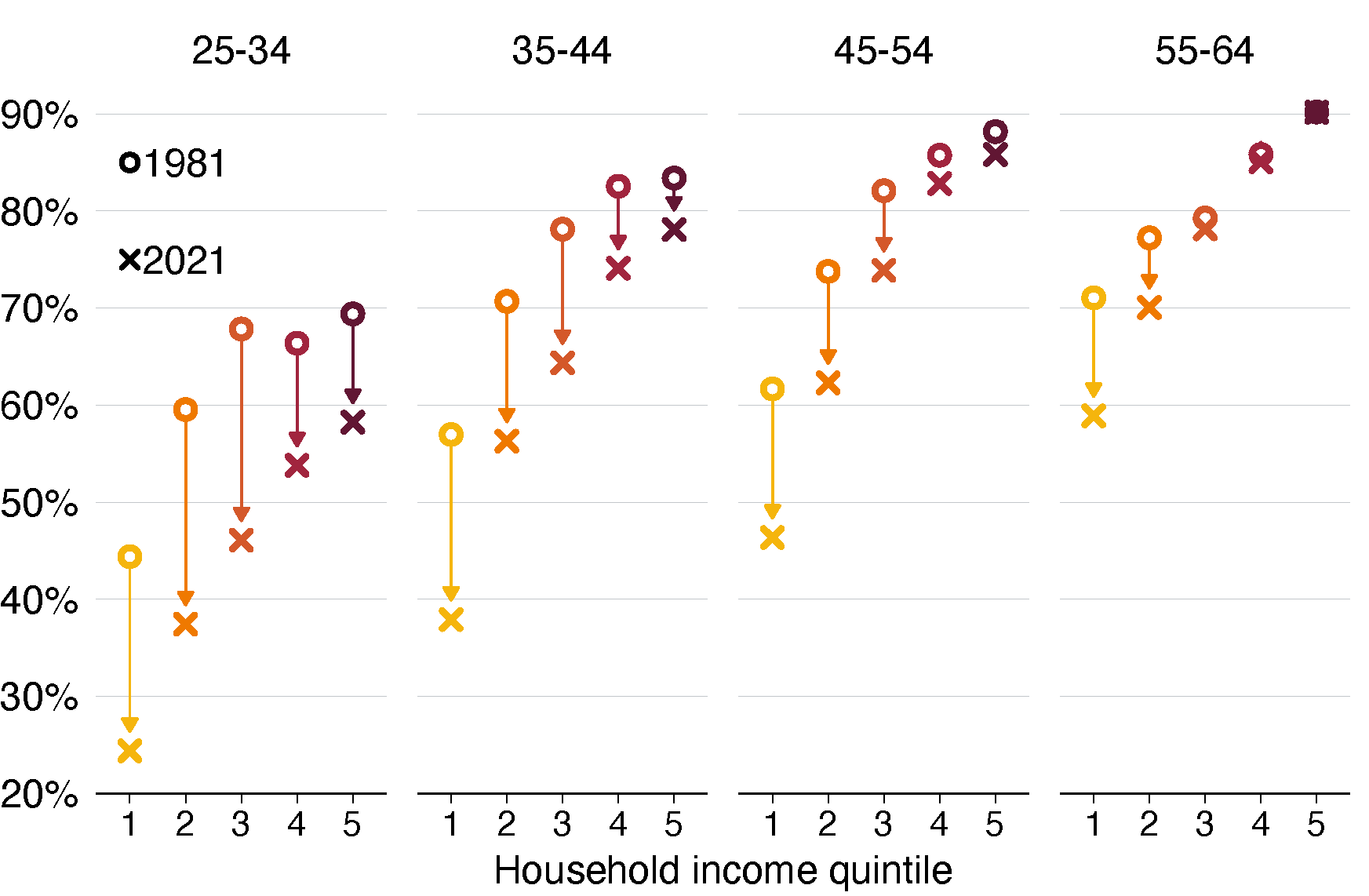

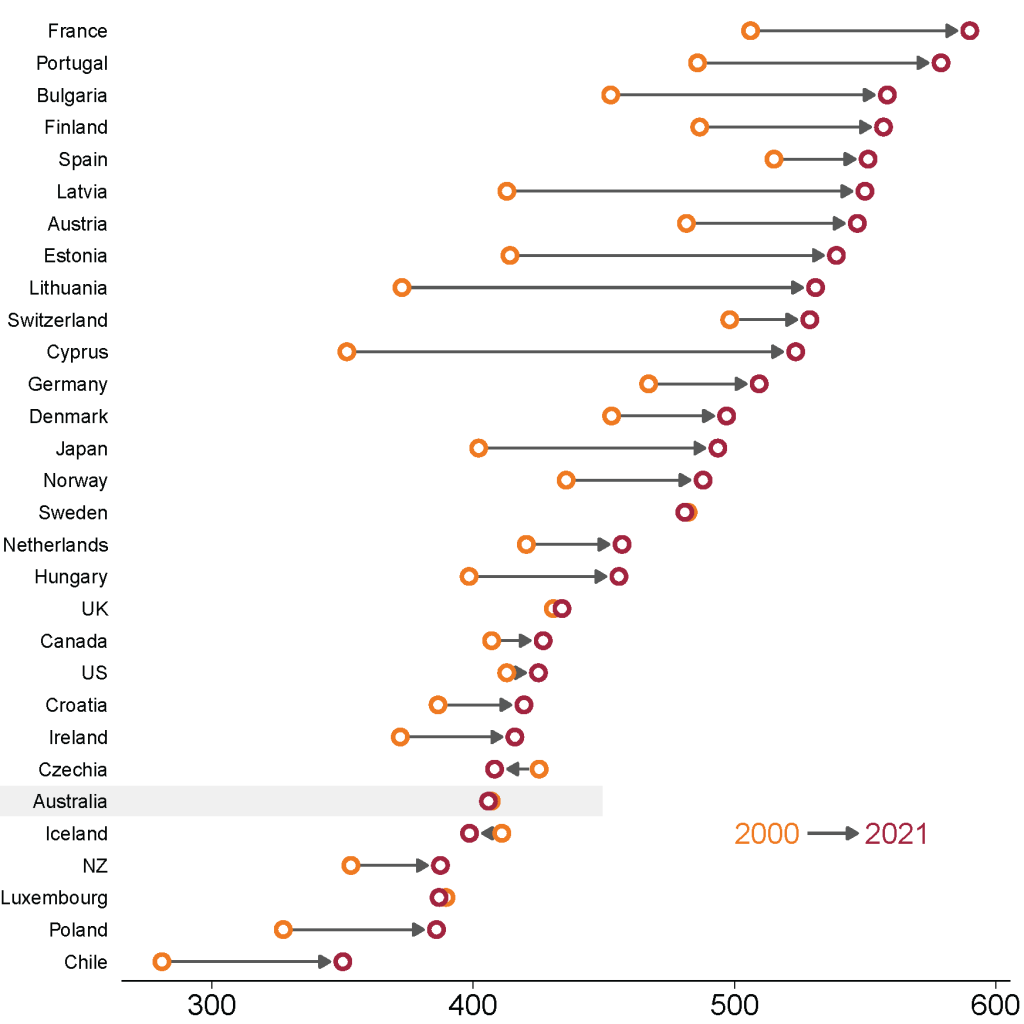

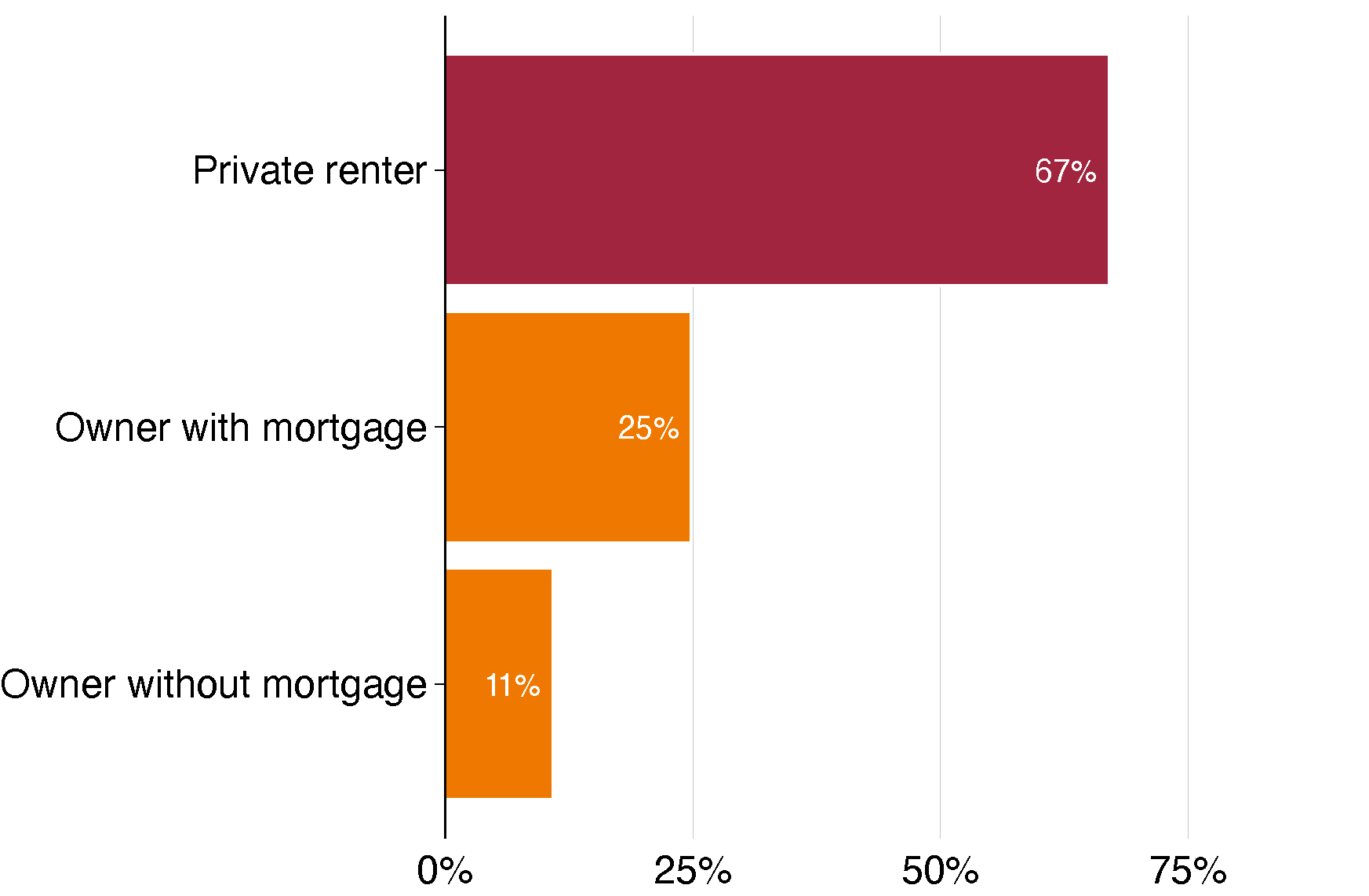

Australia’s housing problems have been decades in the making. Making housing more affordable is a social and economic imperative, and will require relaxing planning constraints, boosting supply, and supporting mobility.

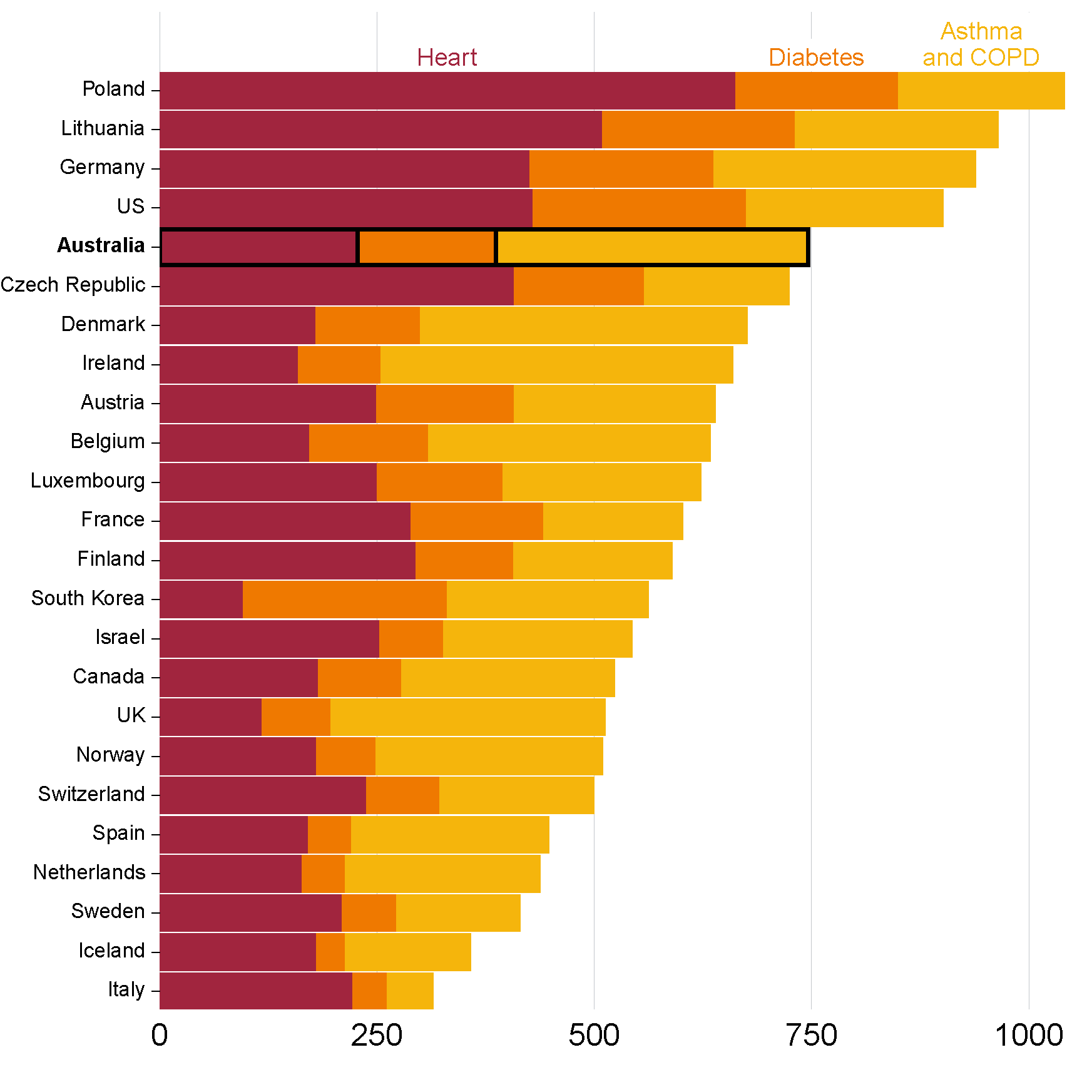

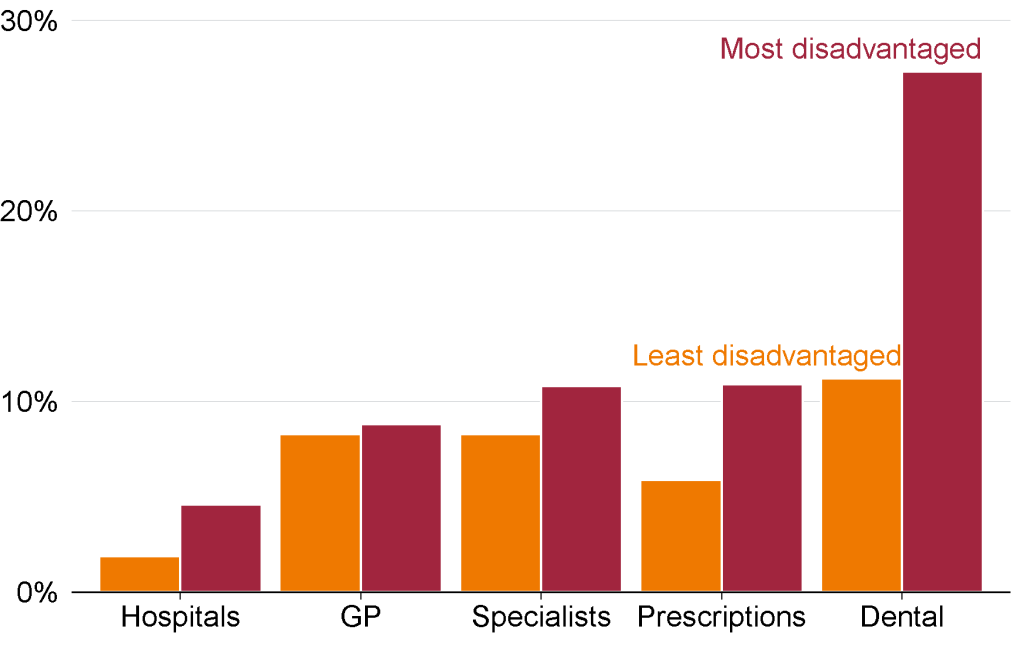

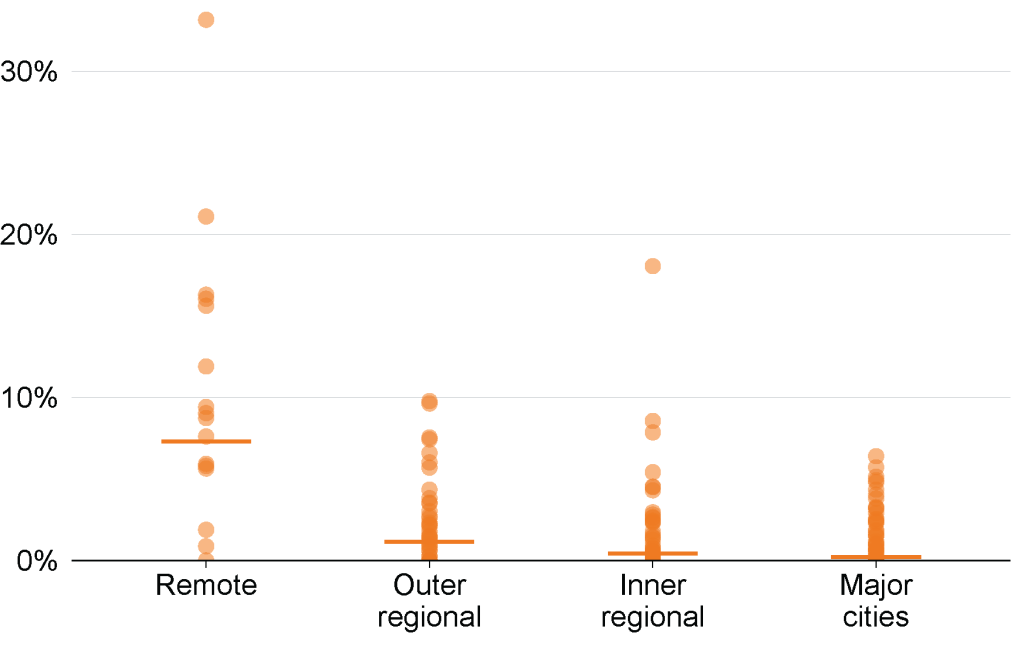

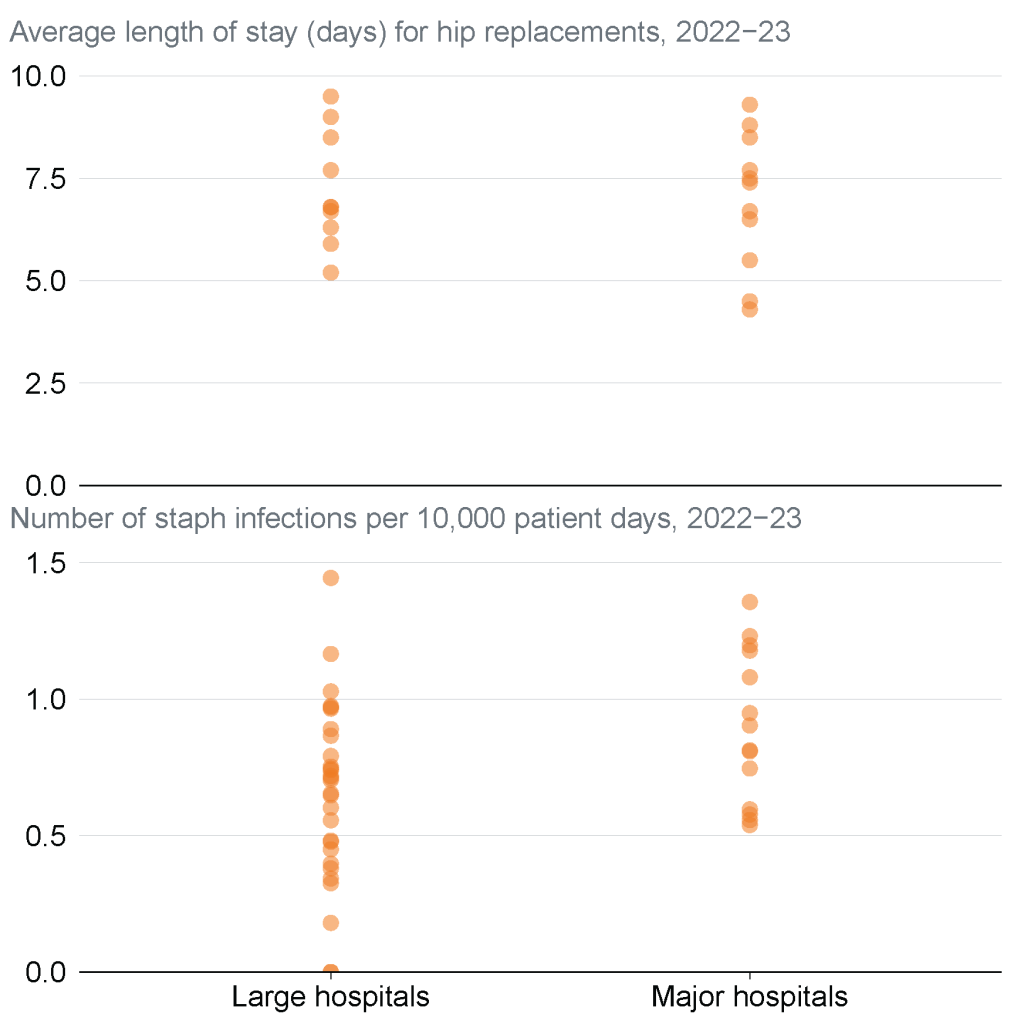

In health, chronic disease is the big system challenge. Australia must adopt a prevention agenda, alongside changes in how GP clinics are funded to support chronic disease management, and a greater focus on hospital efficiency, to help meet growing demand for care.

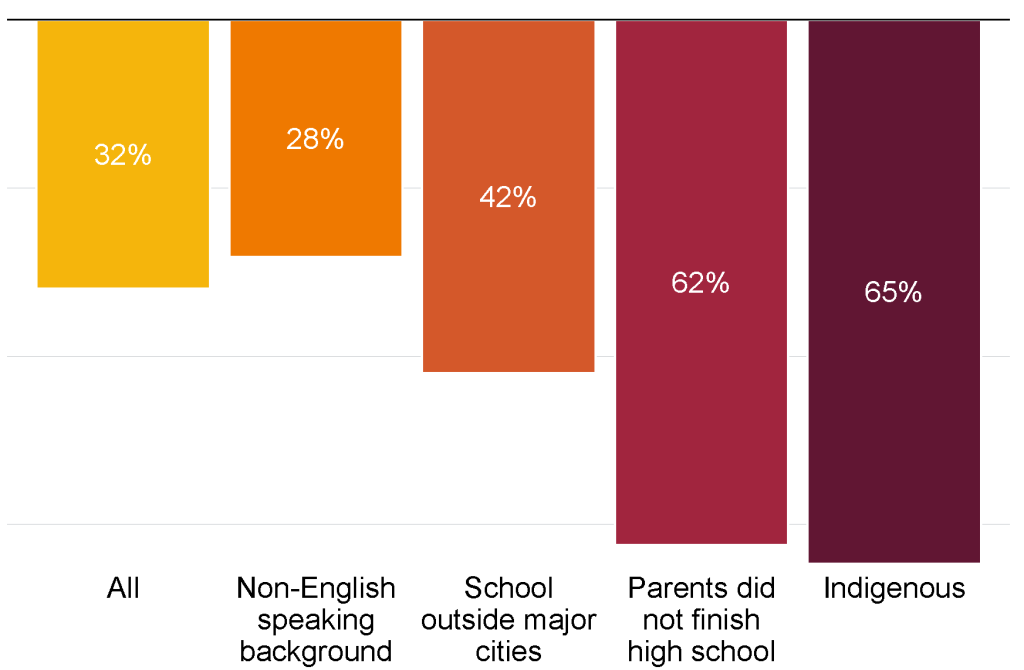

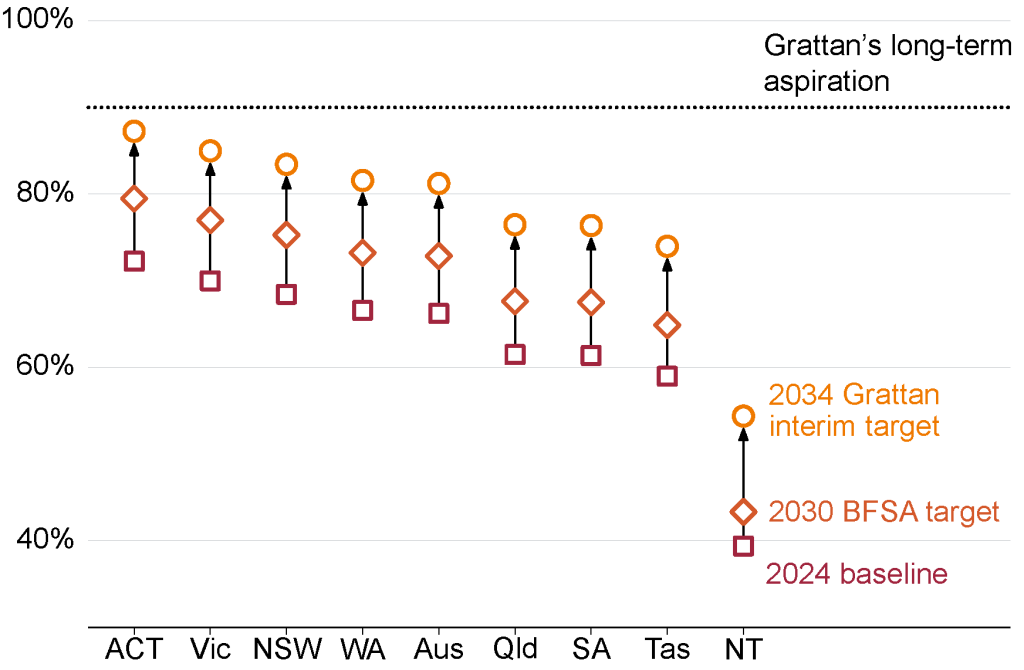

In education, we must lift our game to ensure the next generation of students gains the essential skills.

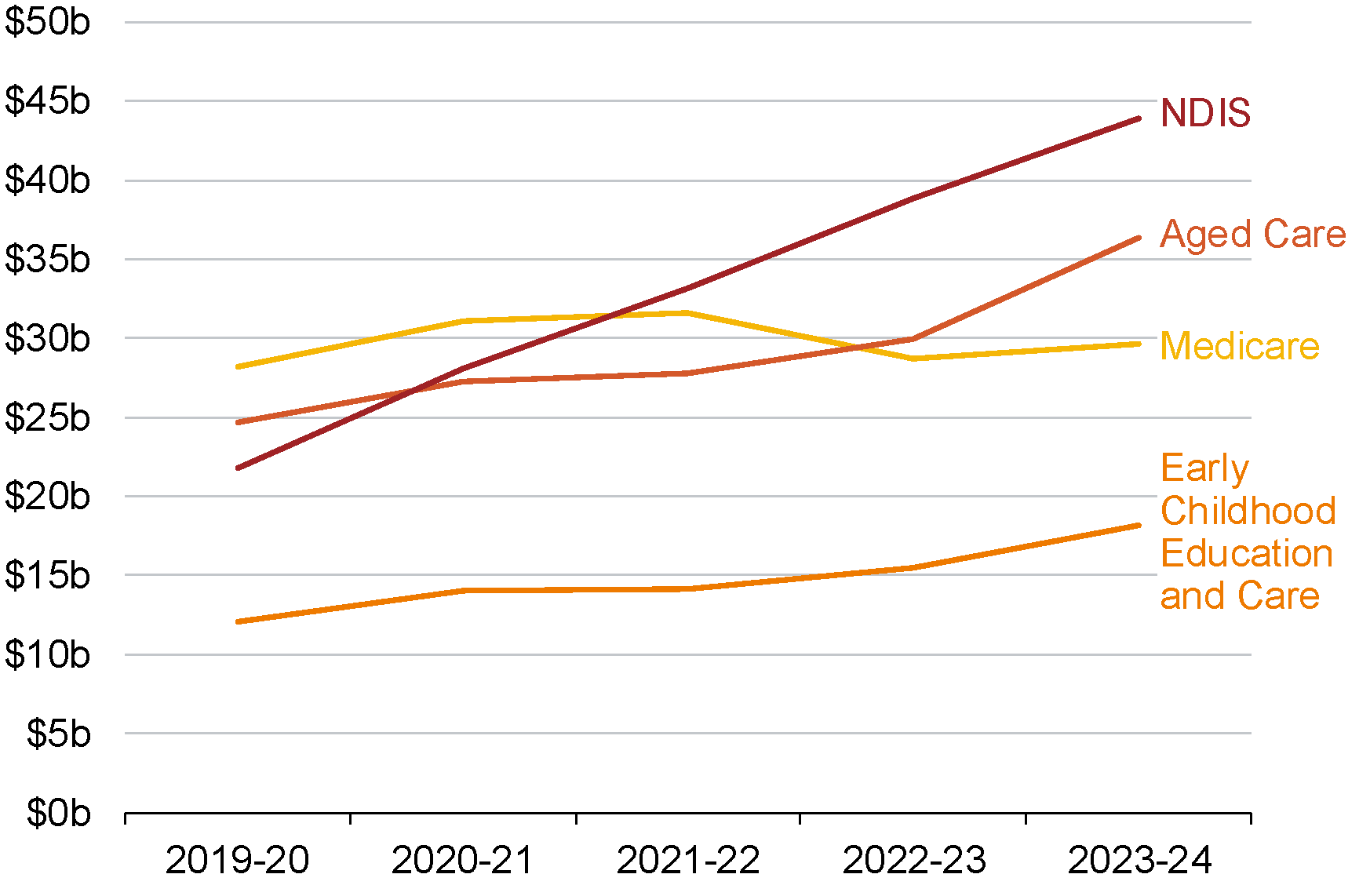

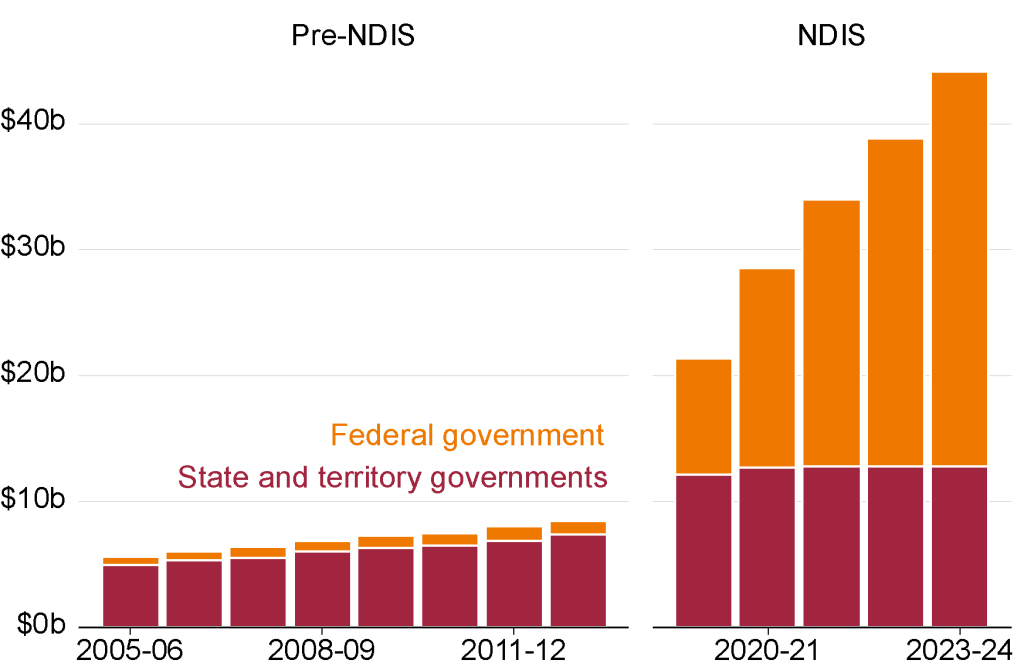

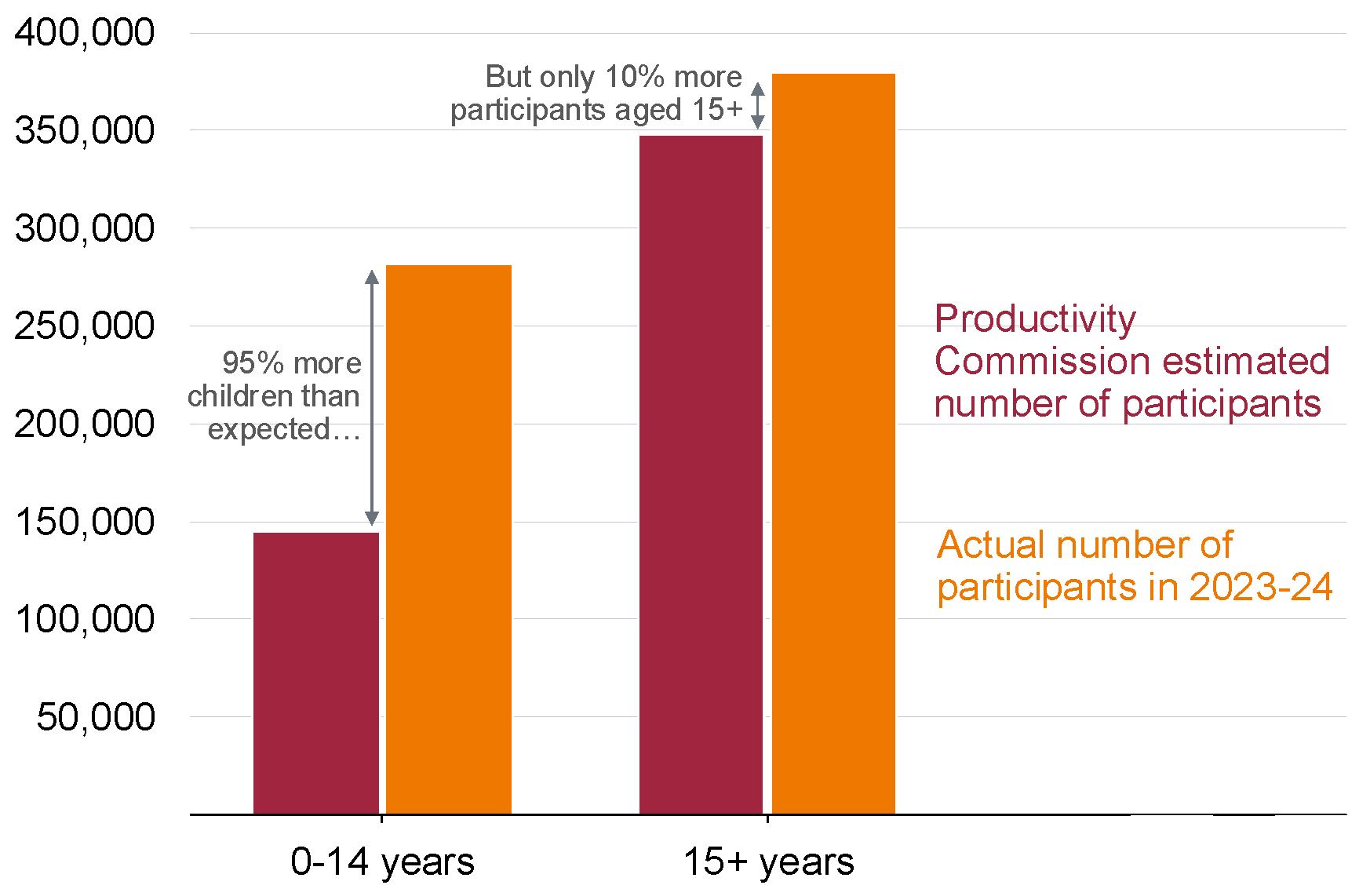

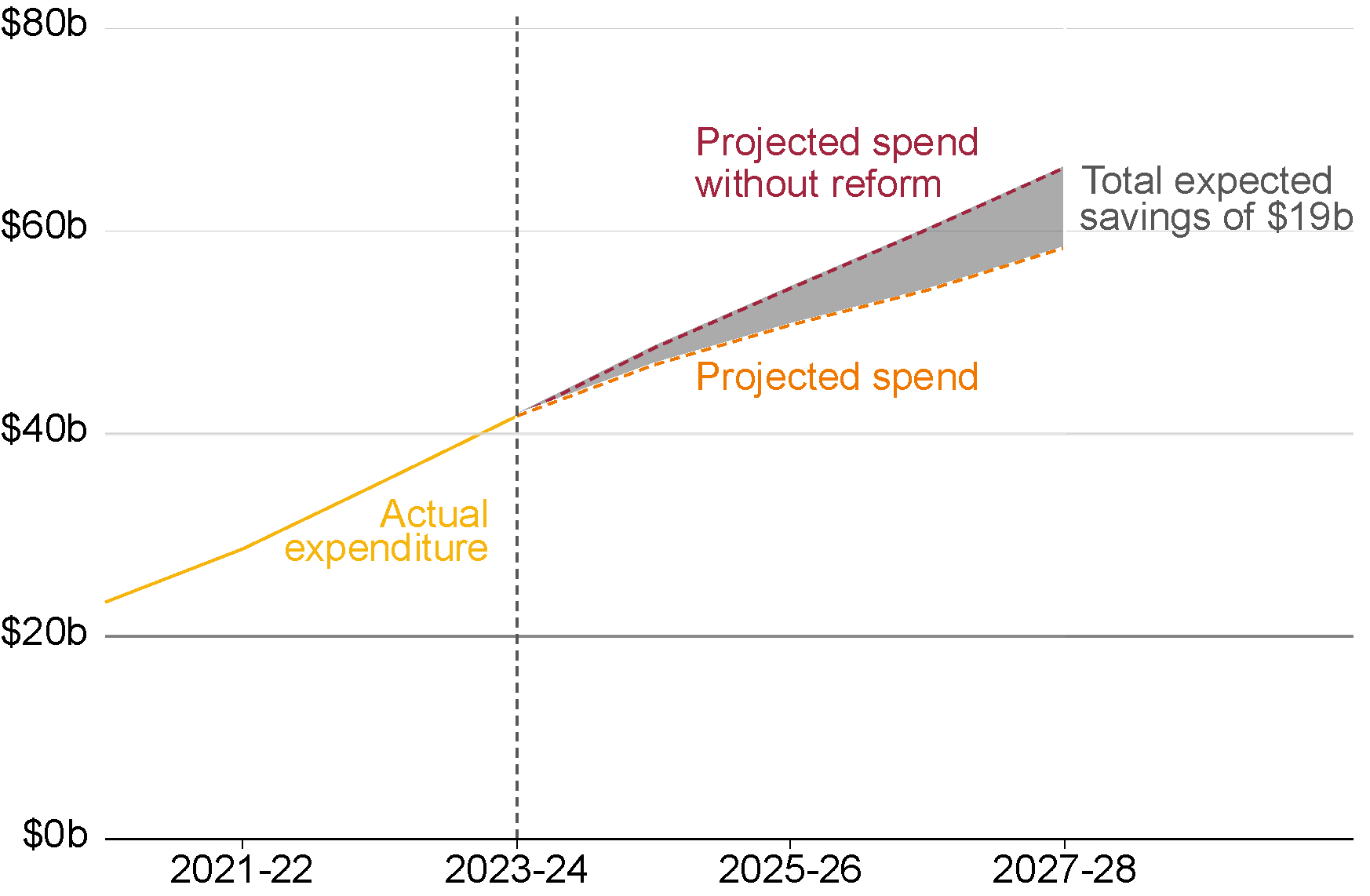

The NDIS provides life-changing support to many disabled Australians, but reforms to build up foundational supports and clarify eligibility for individualised support need to be implemented well to make the scheme sustainable.

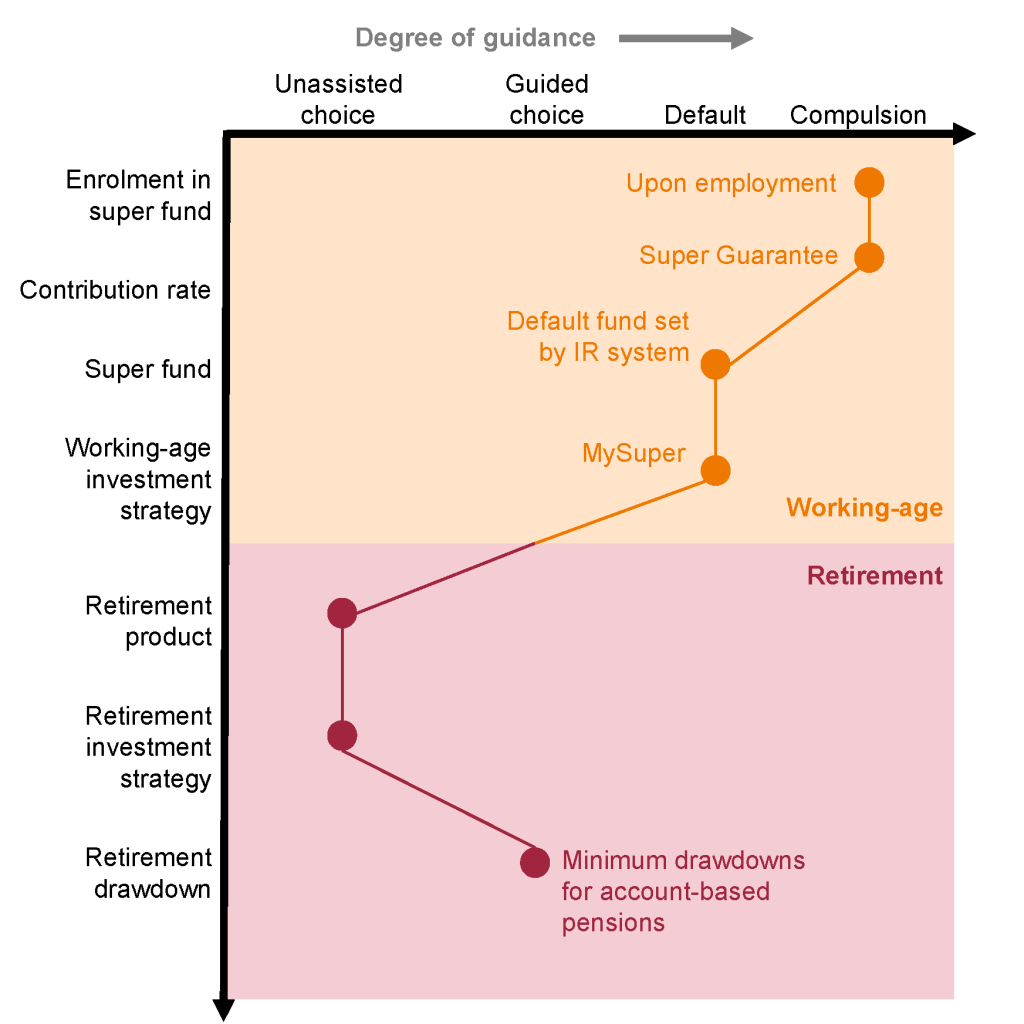

We should also improve our retirement incomes system by simplifying the system for retirees, curbing superannuation tax breaks that cost far too much, and strengthening protections for vulnerable retirees.

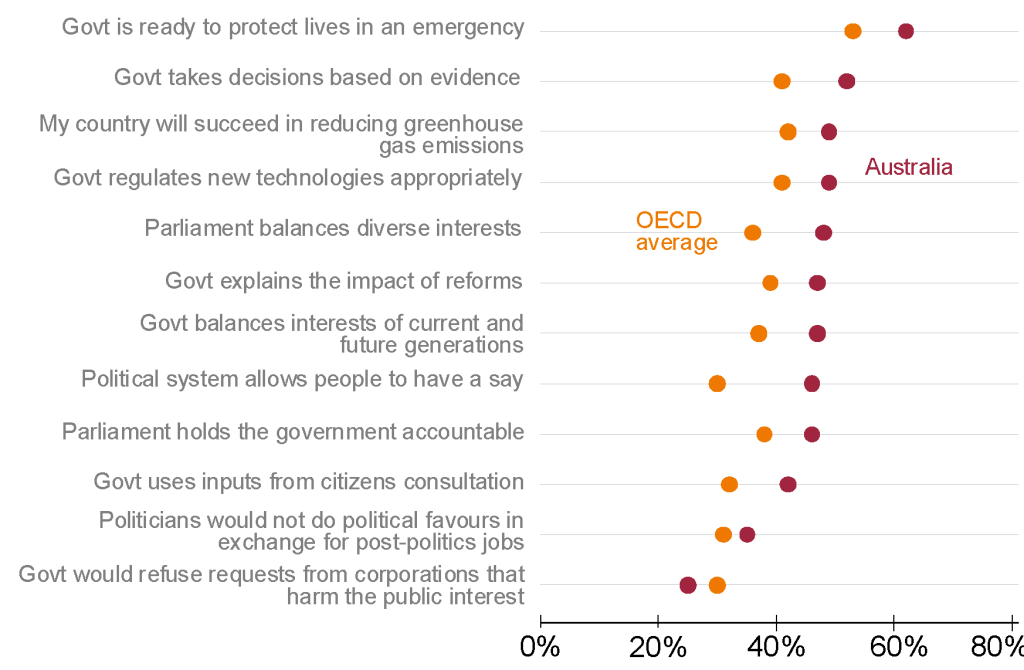

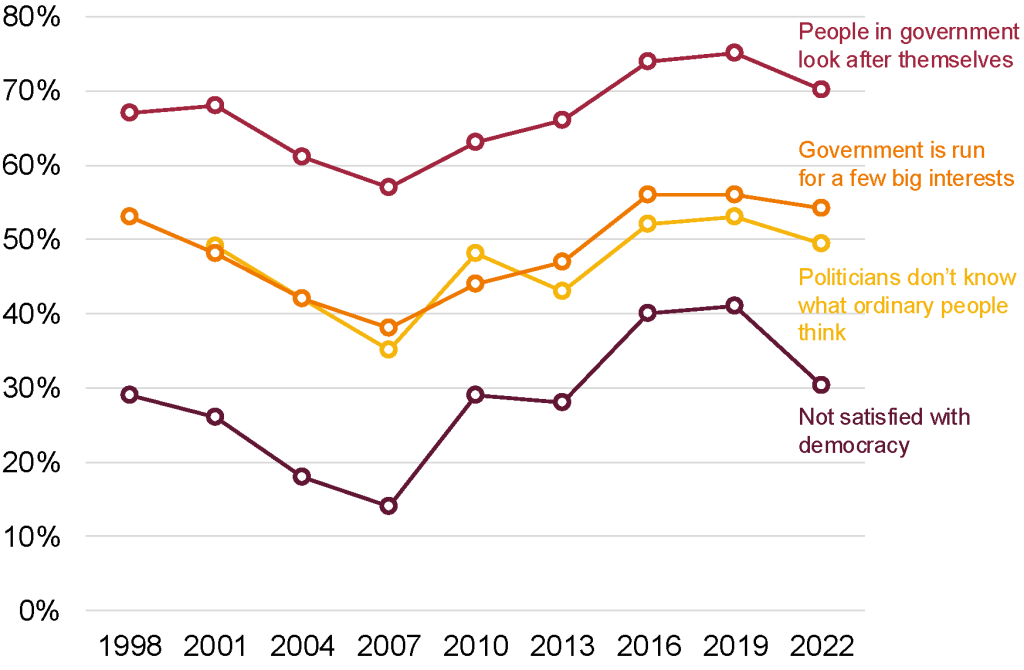

Australia’s institutions remain a real strength. They underpin our resilience to forces we can’t control, and are essential to our future prosperity. But to maintain the trust and confidence of the people, governments should introduce reforms to reduce the influence of vested interests and improve checks and balances on decision-making.

A better Australia beckons. This report shows the way.

A menu of measures to build a more prosperous Australia

Economic growth and budgets

Major reform

- Tax reform

- Simplify skills recognition

- Pathway to universal childcare

Quick win

- Reform skilled migration

- Increase JobSeeker

- Pursue sensible savings

Prepare the ground

- Improve infrastructure and defence procurement

- Unwind the WA GST deal

Net-zero economy

Major reform

- Create a national Net Zero Plan

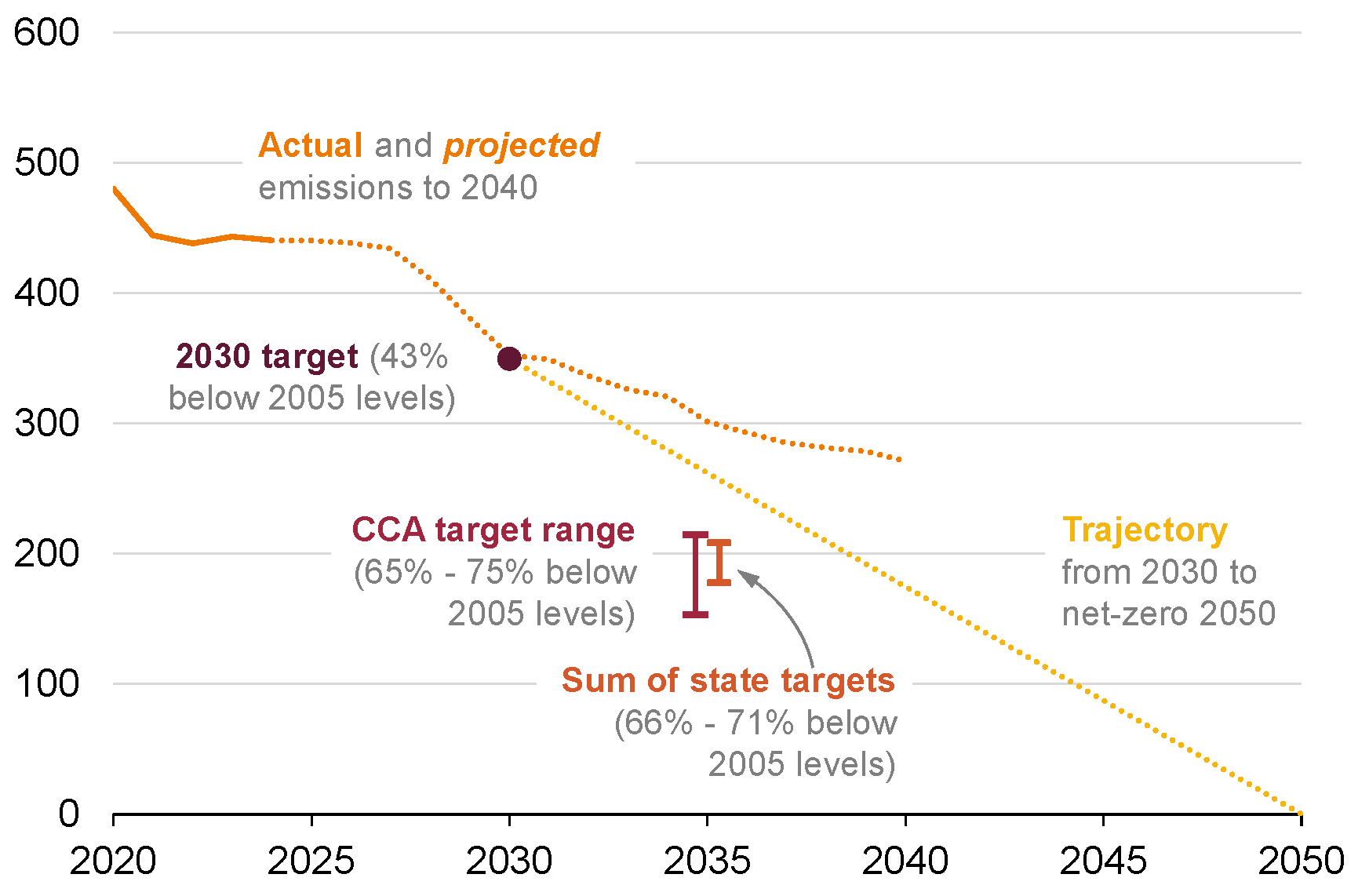

- Maintain the 2030 target and set the 2035 target at 65-75% below 2005 levels

Quick win

- Stay the course on the Safeguard Mechanism

- Stay the course on the New Vehicle Efficiency Standard

- Wind back fuel tax credits

Prepare the ground

- Make the Future Made in Australia framework a comprehensive industry policy

- Introduce an economy-wide, enduring carbon price framework

Energy

Major reform

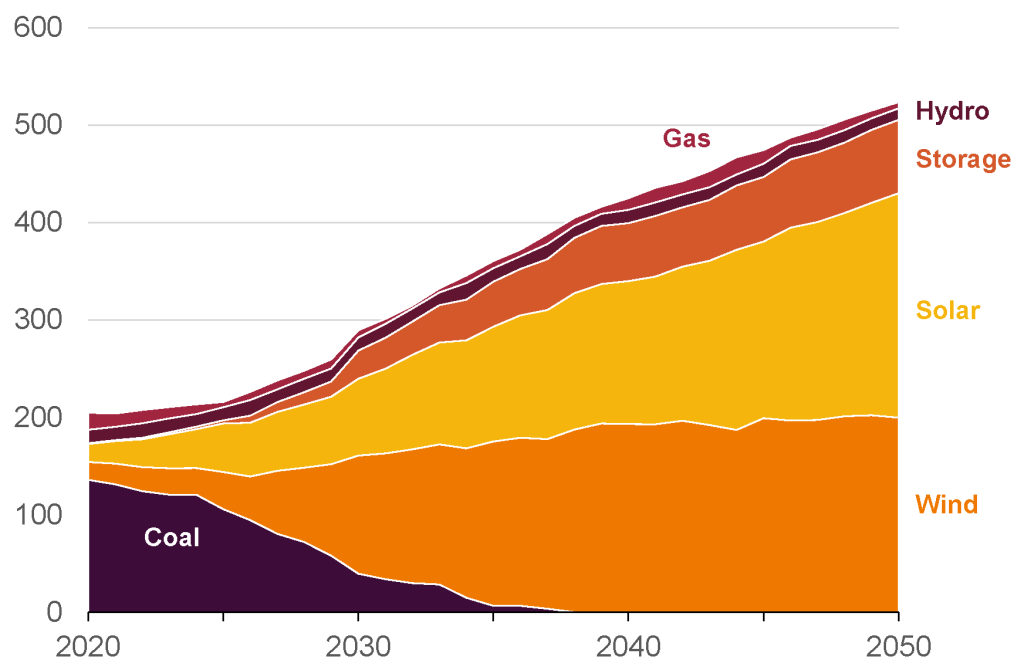

- Develop the post-coal NEM structure

- Address barriers to critical transmission infrastructure

- Fix the Future Gas Strategy

Quick win

- Update the role of gas price caps

- Signal the case for a carbon price to guide investments

- Find a fix for the south-eastern Australia gas shortfall

Prepare the ground

- Extend the role of the Integrated System Plan

- Revisit the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax

- Prioritise under a comprehensive Consumer Energy Resources Integration Plan

Housing

Major reform

- Sharpen states’ incentives to boost housing supply

- Fund states to swap stamp duty for land tax

Quick win

- Further increase Commonwealth Rent Assistance

- Increase the Housing Australia Future Fund

Prepare the ground

- Work with states to improve tenancy laws

Health

Major reform

- Primary care funding reform

- Pathway to universal dental

- Prevention governance and funding – Public specialist investment

Quick win

- Improve vaccination rates

- Introduce better food regulation

- Fund a national secondary consultation scheme

- Get better value from PBS and pathology spending

Prepare the ground

- Establish a health workforce planning agency

School education

Major reform

- Raise expectations for school performance

- Fund evidence-based national professional development courses to upskill schools’ workforce

Quick win

- Invest in an independent quality-assurance process for curriculum materials

- Mandate a Year 1 Phonics Screening Check with a Year 2 re-sit for those students not at benchmark

Prepare the ground

- Strengthen the evidence base and guidance on best-practice instruction

NDIS

Major reform

- Further moderate NDIS growth

- Establish a new National Disability Agreement

Quick win

- Establish an NDIS innovation fund

- Invest in foundational supports using NDIS funds

Retirement incomes

Major reform

- Offer a government annuity

- Further curb superannuation tax breaks

- Create a top 10 list of the best super funds

Quick win

- Performance test account-based pensions

- Assess all retirement products

- Establish a government guidance service

Prepare the ground

- Include more of the value of the family home in the Age Pension assets test

- Review default insurance in super

Integrity

Major reform

- Prevent gambling harm

Quick win

- Boost transparency of lobbying

- Better processes for public appointments, grants, and taxpayer-funded advertising

Media

IN THIS CHAPTER