Summary

Australia expects each of its schools to provide an excellent education that meets children’s diverse needs. But this is difficult work and most schools lack the support needed to achieve it.

Too many children are treading water in schools that struggle to improve academic performance, meet students’ complex needs, or offer a rich set of life experiences. Principals, meanwhile, are straining under the weight of expectations. And teachers frequently find themselves in workplaces that lack the resources and know-how to provide the training and career development essential for a strong profession.

Running highly effective schools is hard. On their own, most schools are too small to marshal the experienced leadership, specialist expertise, and operational nous needed to do this well. While education departments have the organisational heft required, they find it difficult to provide each school with a clear vision for improvement, and precise and practical operational support. And the advice they do provide is sometimes incompatible with day-to-day realities on the ground. Meanwhile, regional supports and collaborative school networks – designed to help tackle these challenges – are limited in the actions they can take to drive real improvement.

The result is a system in which schools are expected to provide an outstanding education, but often feel poorly supported to do so. While Australia has a number of exceptional schools, it has struggled to spread enough success to deliver on its promise of educational excellence for all. And when schools fall short, it is unclear who should bear responsibility, and who should take charge of turning things around.

Establishing multi-school organisations (MSOs) could help. MSOs are strong ‘families’ of schools, bound together through a united executive leadership that is accountable for students’ results.

For this report, Grattan Institute conducted case studies of successful MSOs in England and New York City. Most of these MSOs run schools that are fully-government funded, fee-free, and open to all students.

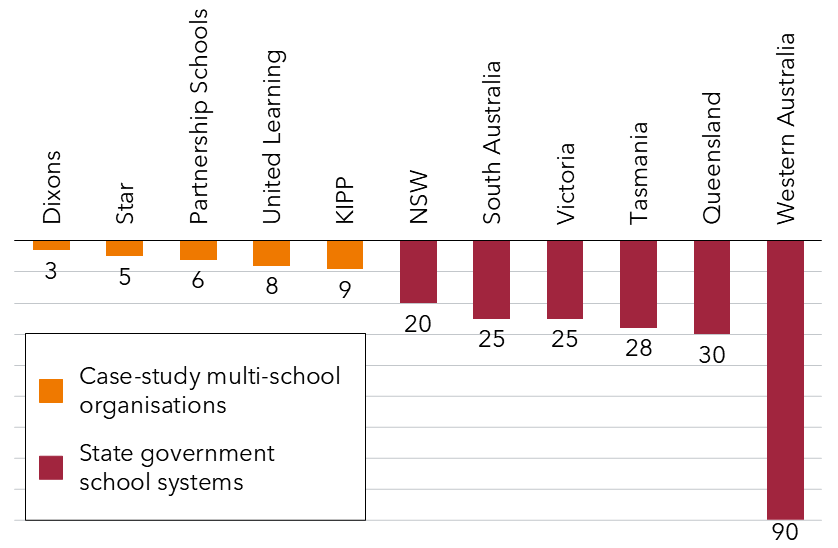

The case studies show that effective MSOs increase the odds of school improvement. Leading strong families of between 10 and 100 schools, these MSOs have a mandate to maintain high standards, and are accountable for doing so. Each has a clear blueprint for running an effective school, and the authority to enact this blueprint across multiple schools, including turning around schools that have under-performed for decades.

Their ‘Goldilocks’ size helps too. These MSOs are small enough to understand – and ‘own’ – the specific challenges their principals, teachers, and students face. But they are also big enough to marshal the resources and expertise their schools need.

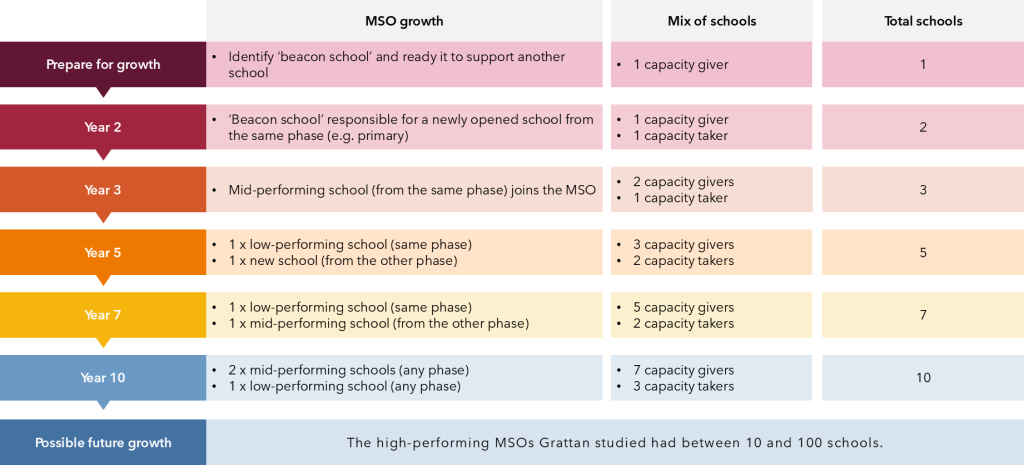

Each Australian school sector should trial MSOs. State and territory governments and large Catholic dioceses should establish multiple trials. Independent schools – especially small ones – should consider trialling MSOs too. Each trial should start with a high-performing ‘beacon’ school, and gradually build to a family of 10 schools within a decade, with further growth possible after that.

While the MSO structure gives schools a clearer shot at improving, it does not guarantee it. Internationally, some MSOs have performed poorly or been mismanaged. Australia should learn from these mistakes and set clear expectations for the trial MSOs. Governments should also establish a robust regulatory framework for the trials, including rigorous public reviews.

Schools need a lot more support to provide an excellent education for all. MSOs offer a powerful way to give schools the boost they need.

Findings

Multi-school organisations are school improvement specialists

- The multi-school organisations (MSOs) Grattan Institute studied are strong families of schools, united under shared executive leadership. In each MSO, schools receive substantial support from a head office team.

- These MSOs ‘own’ the challenge of school improvement, have the authority to implement changes in their schools, and are accountable for students’ results.

- With between 10 and 100 schools, their ‘Goldilocks’ size helps them provide each school with practical support to address challenges ‘on the ground’.

- MSOs can spread the influence of exceptional principals, teachers, and specialist staff, so more students in more schools benefit directly from great leadership.

- MSOs create a formal partnership between schools that helps them share resources and coordinate improvement efforts.

- MSOs learn from every school they improve, accruing knowledge on how to lead a school turnaround, and developing a seasoned group of principals who have ‘done it before’.

Effective multi-school organisations make a big difference for principals, teachers, and students

- MSOs can give principals practical support to help them focus on teaching and learning, and to support them in crises.

- MSOs can take advantage of running multiple schools to offer teachers and other professionals (such as IT and facilities staff) career pathways and professional development opportunities that are not possible in stand-alone schools.

- MSOs can harness the collective resources of their schools to help teachers with curriculum and assessment.

- MSOs can spread best practice across schools, and provide students with enhanced specialist support and life experiences.

Multi-school organisations provide broader system benefits

- MSOs can help train the next generation of teachers, and deliver high-quality professional development for principals, teachers, and non-teachers across an education system.

- MSOs are well-placed to create and share high-quality curriculum materials, as well as research and guidance on establishing and running effective schools.

- MSOs have successfully turned around challenging, under- performing schools.

Governments must play a key role in school education systems with effective multi-school organisations

- While the MSO structure can increase the odds of school improvement, not all MSOs take advantage of the structure and some perform poorly.

- Governments play a key role in setting public expectations for schools, and establishing the policies and regulatory frameworks that ensure multi-school organisations genuinely add value to the schools they run.

Recommendation

Australia should establish several trials of multi-school organisations in each state, territory, and school sector.

Chapter 1: Australian schools are struggling

Many Australian schools are struggling. This is not surprising: governments have underestimated just how hard it is to improve a school.

Too often, school improvement relies on the ‘superhero’ efforts of individual principals. Australia has tried other approaches to school improvement, but none has led to the system-wide improvement needed. As a result, school quality and student results vary widely across the country.

Australian students – particularly those in poor-performing schools – deserve better.

There is another option that Australia is yet to try. Multi-school organisations (MSOs) feature in several education systems internationally. Grattan Institute researchers studied MSOs in England and New York City and found the structure can be a powerful vehicle for school improvement, delivering big benefits for principals, teachers, and students.

1.1 Most Australian schools struggle to boost student achievement

All Australian students deserve the chance to experience a great education, no matter the school they go to. This includes the opportunity to develop strong literacy and numeracy skills, alongside other skills and experiences that will help them thrive in and beyond school.1

In an improving school education system, each new cohort of students should learn more than the students who came before them. By this measure, most Australian schools are stuck.

Average achievement in the past decade has been mostly stagnant. While there have been gains in primary school (between five and six months of improvement in the decade to 2022), these have been largely limited to reading and they have not translated into better results for secondary school students.2

Australia has a long way to go to achieve excellence and equity. About one in three primary and secondary students fell short of the proficiency benchmark in reading and numeracy in the 2023 NAPLAN tests.3 In outer regional and remote schools, nearly half of students did not meet the proficiency benchmark.4 And about two-thirds of Indigenous students were below the benchmark.5

A closer look at school-level NAPLAN data shows that many students are stuck in schools that are consistently performing poorly (see Box 1). Every week that a child is educated in an underperforming school is a week where they risk falling further behind their peers in better performing schools. The costs of under-performance weigh heavily on these students – especially disadvantaged students – and on Australia’s society and economy as a whole.

This troubling national picture persists despite increased spending. Total government spending on public schools in the decade to 2022 grew in real terms from $43 billion to $58.7 billion, an increase of 23 per cent per student.6

More money alone won’t fix this problem. We need another way.

1.2 Expectations on schools are also increasing

Over the past few decades, expectations on schools have increased. In addition to delivering a broad academic curriculum and vocational opportunities, schools are increasingly asked to tackle physical and social issues, such as mental health and well-being, obesity, cyber-bullying, and consent in personal relationships.7 Schools are also now expected to develop students’ broad skills in areas such as digital literacy, entrepreneurship, and intercultural communication.8

The characteristics of the Australian student population are also changing. Teachers report difficulties supporting students with mental health problems, complex behavioural challenges, or disability.9 For example, from 2009 to 2018 there was a 40 per cent increase in the number of students with an identified disability regularly attending mainstream classes.10

The increasing expectations on schools and the complex challenges that many face make it harder for schools to improve.

Box 1: Students in consistently under-performing schools miss out the most

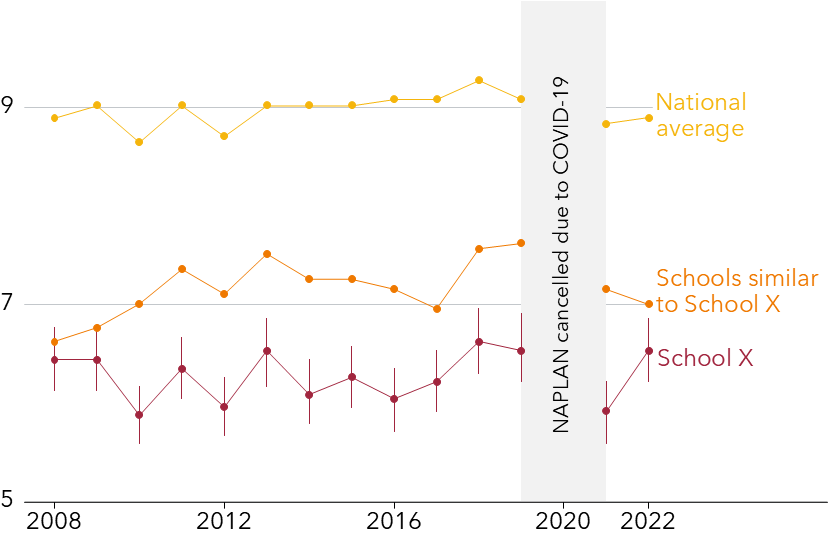

There are 145 schools in Australia where Year 9 NAPLAN reading and numeracy results have been at least 1.5 years behind the national average every year since 2008.a At one of these schools – a large, outer-metropolitan, government school – the average Year 9 student has been reading at about a Year 6 level since 2008 (see School X in Figure 1.1). These students are nearly one year behind students in schools serving students with similar backgrounds, and more than two years behind the national average. The school’s numeracy results are also persistently low.

a. Grattan analysis of ACARA (2023c).

Figure 1.1: The Year 9 reading results of one large school (School X) that is consistently underperforming

Equivalent year level of achievement in NAPLAN

Source: Grattan analysis of ACARA (2023c).

1.3 Great principals are essential, but they should not have to be ‘superheroes’ to improve schools

Principals can have a big impact on students’ achievement, as well as students’ and teachers’ experience at school. A highly effective principal can raise typical student achievement by up to seven months in a single year, and even more in disadvantaged schools.11 But the opposite is also true: ineffective principals can lower achievement by the same amount.

Schools are complex organisations to run, let alone improve. The average secondary school principal manages a budget of more than $15 million, which is more than the turnover of 98 per cent of Australian businesses.12 They are also responsible for managing, on average, 106 staff.13

And the challenges for principals in Australia’s many small schools can be just as significant – about 30 per cent of primary schools have fewer than 10 full-time teachers.14 Those schools are expected to deliver the same quality of education as bigger schools, but with a tiny fraction of the resources.

Principals’ responsibilities include setting their school’s strategic direction, overseeing the curriculum and teaching approach, building teachers’ professional skills, keeping students safe and ensuring their individual learning and well-being needs are seen to, managing the school’s budget and facilities, engaging the local community, and helping students pursue post-school pathways.15

Principals often feel isolated and overburdened by these responsibilities.16 Nearly half of principals who responded to one survey triggered a ‘red flag’ alert, indicating serious mental health concerns, such as risk of self-harm.17

In one Australian study, researchers interviewed 50 principals about the pressure of the role.18 Their reflections included:

You are left in a situation where the buck really does stop with you, from a school level up and system down. When I ask for help, it is usually that it is up to me; it is quite lonely and intimidating.

Government primary school principal, WA

It can be lonely, and you’re certainly not in the job to make friends. You’re there to make the best school and the best local community that you can, and the pressures that come with that can be extremely overwhelming from time to time.

Government early childhood principal, ACT

Australia relies too much on superhero principals to improve schools, one at a time. Those principals who do manage to improve their schools significantly, often do so at great personal cost.19 This can leave principals burnt out by the effort and reluctant to do it again.

1.4 Teachers are struggling and students miss out too

Many teachers are also struggling with the status quo.

In a 2022 Monash University survey of more than 5,497 Australian teachers and school leaders, just 46 per cent of teachers said they felt satisfied with their role, down from 66 per cent in 2019.20 Teachers point to a heavy workload, too much administrative work, ineffective leadership, and poor student behaviour as key obstacles to their job satisfaction.21 And in a 2021 Grattan Institute survey, 74 per cent of the 5,000 teachers surveyed said not having enough support to help students with complex needs was an issue or major issue at their school.22

Individual teachers can’t fix these problems on their own, and many work in schools where principals can’t fix these problems either.

Students feel the effects. Many students, particularly in disadvantaged schools, lack access to rigorous academic subjects, high-quality careers guidance, and a broad set of enrichment experiences.23 Most students who are behind in their learning in Year 3, stay behind right through school.24 This is not surprising, given many schools struggle to implement effective approaches to help students catch up,25 and provide specialist support for students with additional needs.26

1.5 Our current models for school improvement aren’t up to the challenge

Australian policy makers have experimented with different approaches to school improvement. These have included increasing school autonomy with the goal of freeing up principals to better respond to their local communities, creating collaborative networks of schools to tackle common challenges, increasing central education departments’ influence over schools’ operations, and boosting the regional arms of education departments to provide schools with more support.

Within each state and territory, a combination of these approaches is in place.27 These combinations have varied over time as policy makers have sought to find ways to boost school improvement. While each model has a role to play, none address the underlying structural challenges that hinder school improvement across the system.28

School autonomy has increased the burden on principals, without enough payoff

State government policies over recent decades have delegated many decisions to individual principals, such as designing a teaching and learning program, hiring staff, and increasing discretion over how they use their school budget.29

The intention is to increase principals’ freedom to decide what is best for their school. But unless principals have the right resources and expertise in their school, this freedom can make their job harder, leaving them to run their schools as ‘autonomous islands’.30 And encouraging schools to devise local solutions often leaves too much on a principal’s plate,31 and squanders opportunities to solve improvement problems that are common to most schools.

Relying on superhero principals to change one school at a time is an ineffective way to spread success. It is also a fragile improvement model. Even when progress has been made, things can quickly unravel when a principal moves on.32 This is a particular challenge in disadvantaged schools, which tend to have higher principal turnover, making it harder to embed long-term change where it’s needed most.33

Collaborative networks of principals are too loose to coordinate improvement efforts effectively

Schools are often grouped into loose collaborative networks in the hope that this will help them tackle challenges collectively.34 Principals of nearby schools meet regularly in these networks to discuss and reflect on common problems. These informal networks can be a valuable place to share tips and encouragement and can sometimes lead to coordinated efforts across schools.35 But there are several practical reasons why even the best peer-to-peer networks are not well-suited to systematically improving a group of schools.

Schools often take diverging approaches, leaving little room to act together. For instance, two schools may want to work together to improve their English results. But if they study different novels and have different approaches to curriculum planning, pedagogy, and assessment, they will lack the common language needed for meaningful collaboration. As a result, collaboration can add to workloads with little to show for the hard work.

Loose collaborative networks are also poorly suited to turning around schools because they do not give the network’s best schools the authority or funds to spend the sustained time needed to lead change in a struggling school.

Further, these networks rely on the willingness of principals to participate. Sometimes this works, but if nearby schools compete for enrolments and staff, principals may see each other as competitors, not collaborators.36

Education departments find it difficult to give schools precise and practical support

Education departments – and Catholic Education offices37– have the organisational heft needed to address many of the challenges that are too big for stand-alone schools to solve. But they face political and structural barriers to providing the kind of tailored, practical support principals need.

Many operate a vast number of schools. The Queensland, Victorian, and NSW departments, for instance, operate between 1,200 and almost 2,200 schools each.38 Some Catholic Education offices also operate large numbers of schools.39 Attempting to cater for so many schools makes it hard for these departments to create detailed operational policies and provide practical help that is precise enough to be useful to a time-poor principal. Further, the distance between schools and departments means even well-designed improvement initiatives can fall flat.40

Departments also come under pressure to ensure the advice they provide is acceptable to a diverse range of schools and stakeholders. The pressure to balance competing interests and avoid political risk can lead to conflicting policies, a watering down of advice to schools, or a reticence to provide any advice at all. This can hamper principals’ school improvement efforts.41

And even if government guidance is intended as a suggestion, in practice it can be strictly applied by risk-averse principals and departmental staff.42

The exhausting dance of making vague and sometimes conflicting policies work on the ground adds to principals’ administrative workloads and leaves them with less time to focus on improving student learning.43

Education departments also face significant difficulties in closely monitoring the progress of improvement efforts in schools, given the large number of schools for which they are responsible.44 And when principals and teachers do raise valid concerns, it can be hard for departments to change tack quickly or allow exceptions in cases that warrant them.

Regional staff are stretched thin and must contest with high levels of school autonomy to implement change

Most government education departments employ regional staff that provide support to schools in a particular geographical area. Ideally, regional staff – and in particular principal supervisors – would provide the kind of shoulder-to-shoulder support that principals need. But they are frequently stretched too thin.45

Most principal supervisors, often former principals, support about 20 to 30 schools, but some support much more. They broker help from a regional office that has support staff, such as well-being coordinators and attendance officers. But with so many schools to oversee, supervisors tend to focus on supporting schools facing acute crises, such as a collapsed roof or a serious medical incident.

A supervisor’s mix of schools makes it difficult too – they will often have a combination of primary, secondary, and specialist schools operating under very different conditions.

And while supervisors can offer improvement advice to individual principals, high levels of school autonomy in some states and sectors can make it very hard to be directive, especially in relation to teaching and learning approaches. This can thwart supervisors’ attempts to coordinate efforts across several schools, and to implement the urgent changes required in under-performing schools.

1.6 Multi-school organisations can improve the odds of school improvement

There is another way to support school improvement that Australian governments are yet to try.

Multi-school organisations (MSOs) are strong ‘families’ of schools, grouped together under the operational control of an executive leader, such as a high-performing former school principal. The schools in an MSO share joint governance and accountability.46 The ‘formal’ bonds between an MSOs’ schools make MSOs distinct from the loose collaborative networks described in Section 1.5.

Schools in an MSO benefit from precise guidance and substantial support to enact a common blueprint for running an effective school. For example, schools in an MSO frequently use common curriculum and assessment materials, and run shared teacher induction and professional learning.47

The authority of an MSO’s executive leadership to provide this guidance and support distinguishes MSOs from the relationship between stand-alone schools and education departments or their regional arms. The coordination required to implement a common blueprint is hardwired into the MSO structure thanks to the formal bonds between the schools and their executive leadership.48

Schools in an MSO maintain a strong sense of identity connected to their local community.49 Students and teachers feel a connection to their school, but also see they are part of something bigger.

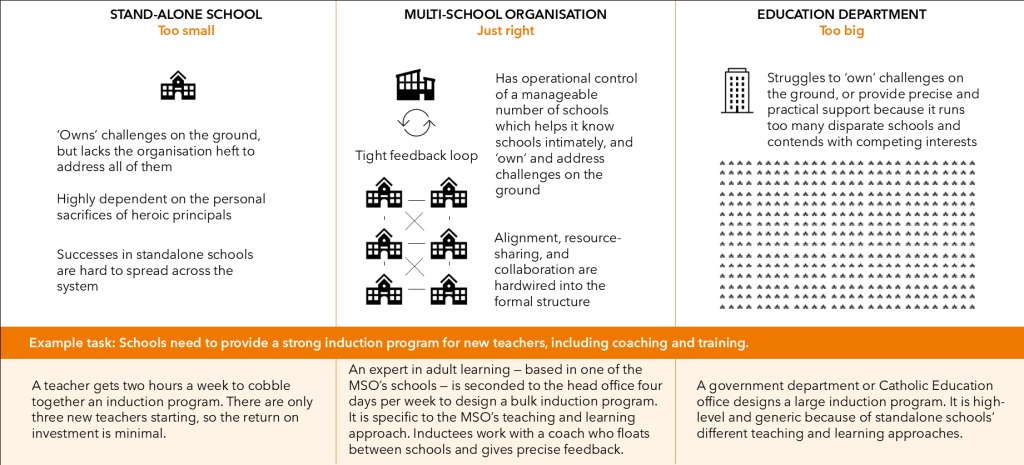

Grouping schools into MSOs creates a ‘Golidlocks’ structure for school improvement (see Figure 1.2). Running at least 10 schools, the size of MSOs is ‘just right’ to ensure the MSO head office understands the types of challenges each of their schools face, while having the authority and organisational heft needed to address those challenges.

But while the MSO structure can boost the odds of school improvement, it does not guarantee it.50 Governments must still establish clear policy goals for education and strong accountability frameworks to ensure all MSOs take advantage of their structure to improve the schools they run.51 But when they do, the results are impressive.

To investigate the opportunities for school improvement created by MSOs, Grattan Institute researchers conducted case studies of six high-performing MSOs in England and New York City (see Box 2).52 To investigate less formal structures, Grattan researchers also visited an organisation supporting – but not directly operating – a group of government schools in New York City.

Box 2: Multi-school organisations in England and New York City

We chose England and New York City as locations for our research because MSOs in both systems educate large numbers of students in free, government-funded schools.

The MSOs we visited in England were all multi-academy trusts – charities which run a group of schools under a single contract with the government. Schools in multi-academy trusts do not generally charge student fees.

Multi-academy trusts have become an important part of government schooling in England. As of January 2023, about 47 per cent of English students were educated in multi-academy trusts.a The English government now sees multi-academy trusts as ‘the best long-term formal arrangement for stronger schools to support the improvement of weaker schools’.b

In New York City, charter management organisations have run fee-free, government-funded schools since 1999. They educate about 15 per cent of the city’s students in public schools, many of whom are economically disadvantaged and from minority groups.c

As well as charter management organisations, Grattan visited an MSO in the Catholic sector, and an organisation providing support to traditional government schools without formally running them.

See Appendix A for more details.

a. See Department for Education (2023a, p. 40). Proportion of students based on state-funded (i.e. government) schools only.

b. Department for Education (2016a, p. 57).

c. See New York City Charter School Center (2023a), noting the demographic breakdown does not distinguish between stand-alone charter schools and schools run by a charter management organisation.

The MSOs we profile in this report serve diverse families of schools. They helped new schools find their feet, propelled good schools to become great, supported exceptional schools to maintain excellent standards of education, and turned around schools with a history of under-performance. Their schools ranged from highly disadvantaged schools, to schools in more affluent areas and even different school sectors – one of the MSOs we studied includes a mix of government and independent schools.

To select the case studies, Grattan researchers sought out examples that took advantage of the MSO structure to improve schools.53 Only MSOs demonstrably adding value to student results were considered. The case studies varied across important dimensions, including size, geographic spread, and school improvement approach (see Table 1.1).

For each case study, the Grattan team conducted interviews and focus groups with staff in the head office and in schools, analysed publicly available student data, and reviewed documentation such as school improvement strategies and curriculum materials. In all but one MSO, Grattan researchers spent two days onsite and visited at least two schools.

Figure 1.2: Multi-school organisations are the ‘Goldilocks’ structure to improve schools

1.7 The structure of this report

This report outlines the benefits of MSOs – as illustrated through Grattan’s case studies – and argues that Australia should trial MSOs.

Chapter 2 describes one MSO – Star Academies in England – and provides a practical example of what the MSO model makes possible.

Chapter 3 explains how MSOs maximise the impact of the best educational leaders: they attract and develop great leaders, empower them to run more schools, and remove many of the distractions that impede their effectiveness.

Chapter 4 shows how MSOs are school-improvement specialists: they ‘own’ the school improvement challenge, have a detailed vision for improvement, are the right size to deliver that vision, and can be held accountable if they fail to improve schools.

Chapter 5 details how MSOs have delivered meaningful innovation across the school education sector.

Chapter 6 recommends trialling MSOs in each Australian state and territory.

Table 1.1: The seven organisations that Grattan visited

England

United LearningTrust

- The largest MSO in England, with 97 schools, comprising 85 fee-free government schools (35 primary, 46 secondary, and four combined primary and secondary schools) and 12 independent schools (which do charge fees)

- Traces history to the foundation of a group of Anglican girls schools from 1884 onwards

- Has taken on more than 50 turnaround schools

Dixons Academies

- Began in 1990 by opening one of 15 schools chosen by the English government to be new innovative fee-free schools, autonomous from the traditional local government-run school systems

- Now runs 17 schools in England’s north: three primary, 11 secondary, two combined primary and secondary, and one senior secondary

- 10 of these schools are turnaround schools

Star Academies

- 33 schools: 10 primary, 22 secondary, and one combined primary and secondary

- Grew from high-performing Islamic faith schools

- Has since taken on 14 turnaround schools

New York

KIPP NYC (Knowledge is Power Program New York City) Public Schools

- Opened in 1995 with one school in the Bronx

- Now runs 18 schools: nine elementary schools, eight middle schools, and one high school*

- Implemented a model of greater alignment between schools

- Part of the national umbrella network of 275 KIPP schools

Success Academies

- Opened its first school in 2006 in Harlem

- 53 schools: 34 elementary schools, 16 middle schools, and three high schools

- The highest-performing MSO in New York City

- Focuses on opening new schools, and replicating its proven model in those schools

Partnership Schools

- Opened in 2013, when the Archdiocese of New York granted full operational control of six of its schools to a charity called the Partnership

- Now runs 11 Catholic elementary schools in New York and Cleveland

New Visions for Public Schools

- Began by running small schools, and now provides support to 71 government middle and high schools in New York City

- Does not govern the schools, making it a less formal arrangement than the six MSOs

*In New York, elementary schools serve students from Prep through to Years 4, 5, or 6. Middle schools serve upper primary students (Years 4 to 6) through to lower secondary students (Years 7 and 8). High schools serve students in Years 9 to 12.

Chapter 2: A look inside a high-performing multi-school organisation

Star Academies (Star) is one of the six high-performing MSOs visited by Grattan. It is among England’s top-performing multi-school organisations. Since its early success with an all-girls Islamic school, Star has opened schools from scratch and taken on 14 challenging government turnaround schools.

Star now educates more than 23,000 students in 33 schools spread across five regions. This includes 22 secondary schools, 10 primary schools, and one combined primary and secondary school.54 The schools are a mix of Islamic faith-designated schools, and secular schools. All are government-funded; no Star school charges fees or selects students based on academic merit.

Over time, Star has systematised its approach to school improvement, and used its size and structure to create opportunities for staff and students that would be near impossible in a stand-alone school. Today, Star seeks to give back to the education system and improve the quality of education for children attending other schools.

2.1 Star Academies’ origins

The first Star school was founded in Blackburn, Lancashire, in 1984. Blackburn is a socially disadvantaged town in the north of England. A textile hub during the Industrial Revolution, its economy was hit hard by the decline in Britain’s cotton industry. Blackburn remains an area of high deprivation: in the 2021 Census, it was ranked the 10th most income-deprived area out of England’s 316 local government areas.55

In this context, Star’s founding school – Tauheedul Islam Girls’ High School – has achieved impressive results. It became a fee-free government school in 2006.56 In 2007, 82 per cent of its students passed five or more General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) exams, compared to 47 per cent of students nationally.58 And in 2023, 94 per cent of its students scored a strong pass in the GCSE English and Maths exams, compared to 45 per cent of students nationally.59

2.2 Star Academies’ impact

Building on this success, Star’s mission is to create outstanding schools that promote educational excellence, character development, and service to communities. Star is committed to improving the life chances of young people facing disadvantage. In the words of its Chief Executive:

Ultimately the mission is to make a difference in the lives of young people. We go where we are required, to the toughest areas. And if we’re successful then we’ve created opportunity and we’ve given someone a lifeline.

Thirty-one per cent of Star students are economically disadvantaged (compared to about 24 per cent nationally), and 39 per cent have English as an additional language (compared to 20 per cent nationally).59

Star has had remarkable success in helping children succeed. In 2023, it was England’s top-performing MSO, measured by the value added to students’ learning.60 Star’s 2023 Year 11 cohort were, on average, about 14 months ahead in their learning compared to Year 11 students nationally who had a similar Year 7 starting point.61 Star’s disadvantaged students in this cohort made on average 18 months more learning progress between Years 7 and 11 than disadvantaged students nationally. Star students frequently land a spot at top-tier universities, and 9 out of 10 Star students go on to education, employment, or training (compared to fewer than 8 in 10 nationally).62

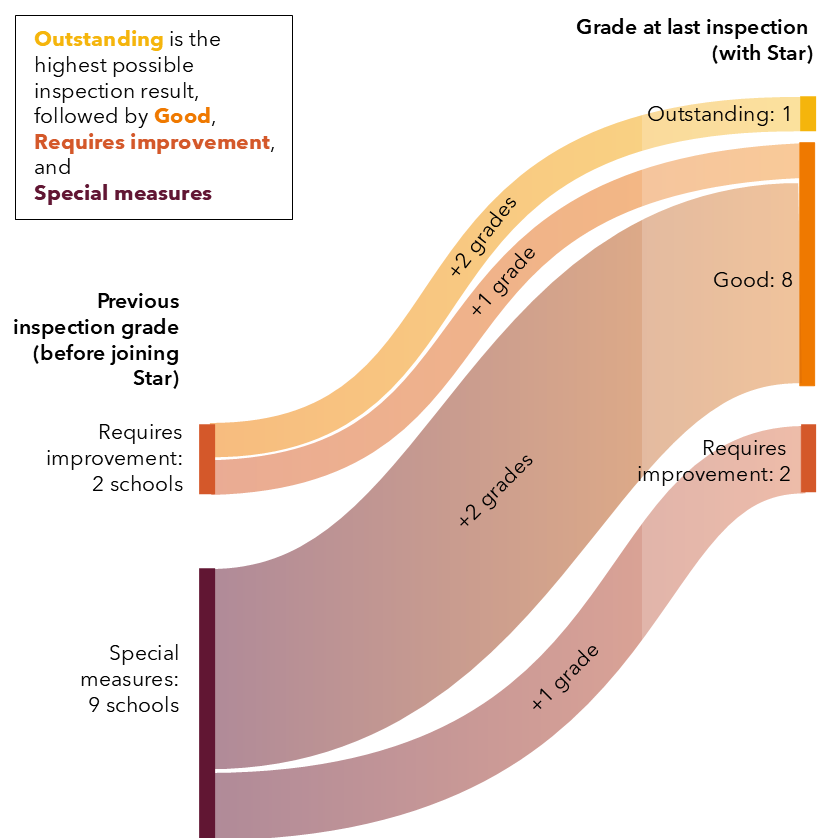

Star’s schools have a reputation for excellence. Schools in England are inspected by teams of independent, trained inspectors who judge the school’s overall quality as either ‘outstanding’, ‘good’, ‘requires improvement’, or ‘inadequate’.63 Schools in the latter two categories are considered to be under-performing, and may be required to join a multi-academy trust or switch to a different one.

Star has strong inspection results: about 50 per cent of its schools have been judged ‘outstanding’, compared to only about 18 per cent of schools nationally.64 Its first school, Tauheedul Islam Girls’ High School, has been judged ‘outstanding’ at four consecutive inspections.65 All under-performing schools that have joined Star have received improved grades on inspection (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: The 11 ‘turnaround’ schools that joined Star have all improved their inspection grades

Source: Ofsted (2023b).

2.3 Star Academies’ school improvement strategy

As Star grew and sought to spread its success, it distilled lessons learnt into a formal school improvement strategy.

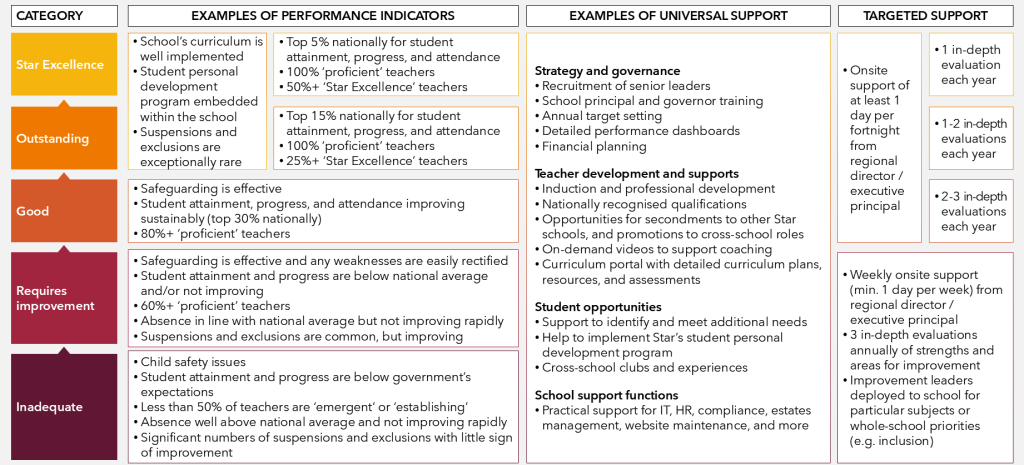

The strategy sets a clear goal for Star schools to work towards ‘Star Excellence’. Tauheedul Islam Girls’ High School is an example of a school achieving ‘Star Excellence’, meaning it is in the top 5 per cent of schools nationally for student achievement, progress, and attendance, among other things.

Star places its schools on a continuum of four ‘categories’ on the path to Star Excellence (see Figure 2.2).66 These categories are accompanied by specific, and often intensive, supports provided by the head office team.

All Star schools receive universal support, including exemplar curriculum and assessment materials, whole-of-organisation curriculum masterclasses, guidance and practical help to assist and extend students who have additional needs, and detailed data dashboards.

Star schools also get targeted support tailored to their needs. For the schools needing the most support, the principal’s supervisor is on-site at least one day per week. For schools approaching Star Excellence, support is lighter touch.

Figure 2.2: An example of how Star tailors its support to schools’ needs

Source: Adapted from Star Academies (2022a).

2.4 How being a multi-school organisation helps Star improve its schools

Star’s school improvement strategy is made possible by the MSO model. With the shared resources and expertise of 33 schools, Star can tackle challenges that would be very difficult for a stand-alone school to overcome.

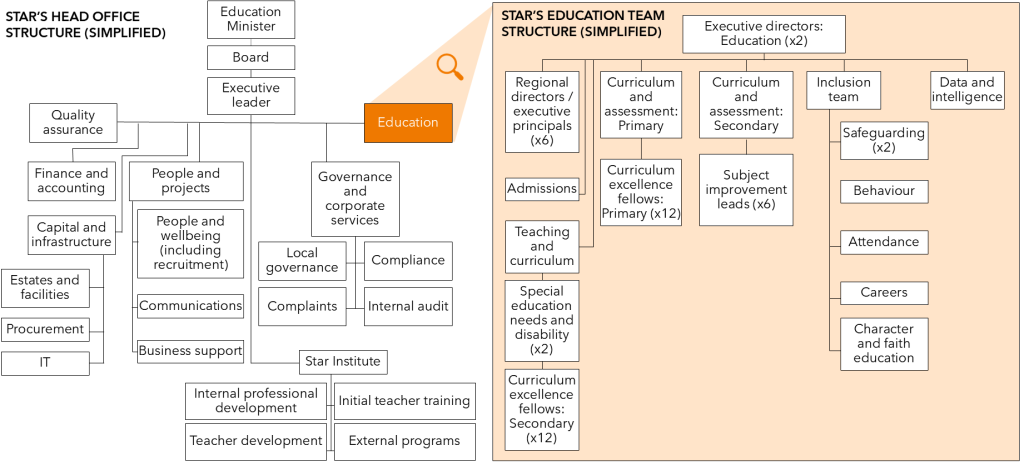

Star’s sophisticated organisational structure (see Figure 2.3) means that leaders in schools can call on experts who have a deep knowledge of the school’s context, and share a commitment to Star’s mission and vision for improvement.

Figure 2.3: Star’s shared head office team provides practical, high-dosage support to schools in a range of areas

Source: Star Academies (2023). Provided to Grattan on request.

Teaching and learning

High-quality curriculum and assessment are pivotal to Star’s school improvement strategy.

Star aims to teach students about the world around them. For example, in Year 5, students compare two pieces of 19th Century Romantic music. And in Year 6, students investigate the history of the Mayans.

Each Star school’s curriculum is reviewed twice a year. Schools found to need help get it.67 Schools adopt and adapt high-quality curriculum materials and assessments, including:

- long-term curriculum plans, which detail the sequence of topics taught for each subject in each year level;

- unit plans, which detail what students will learn in each lesson, explain how to address misconceptions, and suggest adaptations for students who have additional needs; and

- exemplar lesson materials, such as handouts, presentations, and quizzes.

The availability of these materials reduces teachers’ workload and increases their effectiveness in the classroom. One beginning teacher told us how these materials enhanced her teaching and enabled her to coordinate extra-curricular activities:

It definitely gives you the time to focus on those adaptations to make sure they’re right for your group, and also to focus on things like feedback and marking. Had we not had the centrally pooled resources to alleviate time spent planning, I might not have been able to offer the Duke of Edinburgh Award program. It’s also about not feeling that you have to go home and spend three hours in the evening planning lessons.

The shared curriculum makes it possible for all Star schools to use common assessments to track student progress. This enables Star to benchmark results, so leaders know how their students are progressing compared to students in other Star schools.

Common assessments also help Star’s head office team identify particularly strong practice – such as a Humanities department with above-the-odds results – and find out what is driving that success.

Common curriculum and assessments also anchor staff professional development. For example, English teachers from across the schools can discuss how they will unpack a particular passage in Macbeth, including what went awry last time they taught that lesson. Primary school teachers teaching the same unit on volcanoes can compare how they plan to explain difficult vocabulary, such as ‘caldera’ and ‘geyser’, and share exemplary student work to show as a model in their class.

Being an MSO has helped Star design and implement a comprehensive reading strategy across its 22 secondary schools. The strategy includes daily 20-minute read-alouds by home-room teachers, to improve students’ vocabulary and reading fluency (students follow along with their own copy of the book). The strategy ensures that, by graduation, every student will have read 24 books through the daily read-alouds. To support this strategy, Star purchased class sets of books, and created pacing guides and discussion prompts for teachers.

Star has selected assessments and designed dashboards to monitor the impact of the reading strategy. Leaders told us that reading a common set of books had fostered a love of literature and created a sense of community across Star schools.

The early results are promising: within one year, the percentage of fluent readers rose by 6 percentage points. Among students with special needs or a disability, the percentage of fluent readers rose by 9 percentage points.68

Teacher and staff opportunities

Running a group of schools also enables Star to offer more opportunities to staff. Staff benefit from a range of hands-on professional development opportunities that a stand-alone school would be hard-pressed to deliver. This includes induction programs, specialist training for middle leaders, and training for non-teaching staff.

Teachers attend organisation-wide curriculum excellence masterclasses for all subject areas. School office staff can get training on talent acquisition or website design.

The MSO structure has also created opportunities for career progression at Star. Now more schools benefit from Star’s most skilled practitioners: a stellar Maths teacher can take up a part-time secondment to Star’s head office to develop curriculum materials and assessments for use across all Star schools; a principal might be promoted to a regional director or executive principal role to work closely with five Star principals; and a talented groundskeeper might take on a regional site manager role, responsible for overseeing facilities at several schools.

Student opportunities

Students also benefit from Star’s size and the aligned practices across its schools. Star can offer them opportunities across its 33 schools that each school may not have been able to offer alone.

Star’s ambitious curriculum ensures students encounter a breadth and depth of academic knowledge, no matter which school they are in.

The MSO model also creates rich opportunities outside the classroom. All Star schools have a leadership focus, which pushes students to grow as leaders, engage in school life, and give back to their local community. This includes a variety of opportunities that are often not available in a stand-alone school, such as Star-wide sports competitions, creative and performing arts events, and career and enterprise programs.

Social action initiatives are an ingrained part of school life at Star. In the 2022-23 academic year, for example, Star students raised more than £466,000 for charities and social causes.69 Collectively, Star students spend about 150,000 hours each year volunteering in their communities.70

During the pandemic, Star’s size helped it loan 5,000 devices to disadvantaged students so that they did not miss out on learning.71 It also trained 135 staff in mental health first aid, and 100 pastoral staff to provide extra bereavement support to students.72

2.5 How Star is advancing education beyond its schools

Star has helped improve education beyond the 33 schools it directly runs.

Star runs School-Centred Initial Teacher Training: a 12-month, employment-based program to become a qualified teacher for career changers and graduates from non-teaching degrees. Since 2017, 246 trainees have become qualified teachers with Star’s support.73

Star is also a founding member of the National Institute of Teaching, which will offer a two-year program for 2,000 beginning teachers, and a development program for up to 650 National Leaders of Education, between 2022 and 2025.74 As part of its involvement, Star will help to develop the curriculum, host trainee teachers and leaders, and provide its data for longitudinal research on what interventions best boost students’ learning.

2.6 An example of Star’s school improvement – turning around Bay Leadership Academy

Bay Leadership Academy joined Star in the 2018-19 academic year. Within three years, the school had made substantial improvements.

Bay Leadership Academy is in Morecambe on England’s north-west coast. It is an area with a very high crime rate and several selective schools that attract academically capable children from aspirational families away from non-selective government schools.75

Bay Leadership Academy is a no-fee, non-selective government school that serves 705 children aged 11 to 18 who are mostly from working-class backgrounds. About 46 per cent of its students are disadvantaged, which is nearly twice the national rate, and 40 per cent start at Bay Leadership Academy behind in their learning, compared to about 22 per cent nationally.76

Before joining Star, Bay Leadership Academy had entrenched underperformance – the schools inspectorate had never graded it as ‘good’. It had a poor reputation, and few families wanted to send their children there. Student behaviour was unsafe, and curriculum and assessments were ad hoc.

The school’s governors knew it needed to change. One told us:

It was obvious that the school needed to join a family of schools, not these soft federation things where people just go to meetings and chat to each other. We needed a structure where somebody at the top had really clear expectations about what was going to happen.

After joining Star, the school rapidly improved. An interim principal was appointed, with a brief to raise student and teacher expectations. Star’s behaviour policy was implemented.77 It clarified the ‘red line’ behaviours that would not be tolerated. Examples include racist language or behaviour, bullying, truancy, and refusing to hand over a mobile phone. Star appointed an expert to set up the School Inclusion Centre, which gives targeted support to students who consistently behave poorly.

When it joined Star, the school was not a physically inviting place to learn. Star provided financial support, and helped give the school a face-lift and make it a safer environment for students.

Teachers also received more support. On advice from Star leaders, the school reduced the variety of subjects each teacher taught, so they could deepen their curriculum expertise. Teachers who were previously planning mostly on their own, could now use Star’s curriculum and assessments and adapt them to their students. Heads of departments were provided with detailed insights from the Star data team, to help them determine which students needed more support and key topics for staff professional development. Star’s head office arranged training for the school’s leaders on curriculum and coaching.

By 2022, the school had improved markedly despite the pandemic, though there is work ahead to maintain stable results and reach Star Excellence. It received its first ever ‘good’ inspection result in 2022.78 In the 2017-18 academic year – before the school joined Star – just 9 per cent of students entered the English Baccalaureate: a broad set of academically challenging subjects that keep students’ options open for future studies and careers.79 By 2023, 69 per cent of students at Bay Leadership Academy had entered the English Baccalaureate.80 Parents now queue up on open day and the school gets more applications than it has places.

The atmosphere at the school has changed too. Staff and students feel like they are part of something bigger. Discussing the impact of the Star Awards night – an event which brings the 33 schools together to celebrate demonstrations of Star’s values – one Bay Leadership Academy teacher told us:

When my student won the Star Art student award, it was a really proud moment for the school. Because we’re part of Star, that’s now recognised nationally. This gives students a sense of pride and determination to push themselves.

Bay Leadership Academy now also contributes back to Star. For example, some of its teachers have been filmed in short videos used for professional development for teachers within and outside Star. And the Science Department has also worked on refining the Star-wide Science curriculum.

Chapter 3: Multi-school organisations can make a big difference for principals, teachers, and students

High-performing MSOs, such as Star Academies in England, can take advantage of their ‘Goldilocks size’ and the coordination possible through the MSO structure to make schools a better place for principals, teachers, and students.

MSOs can spread the impact of an education system’s best leaders across more schools, and take a load off time-poor principals. They can provide practical support for teachers, and offer greater opportunities for professional enrichment and rewarding career paths. For students, MSOs can coordinate and build on individual schools’ efforts to provide specialist support in areas such as disability and inclusion, and offer a broader range of academic and extra-curricular opportunities.

3.1 Multi-school organisations can improve school leadership

Great leaders make schools great. But Australian principals juggle too many distractions to lead improvement effectively, and the status quo does not make the most of the country’s best principals.

MSOs can extend the reach of the best principals, and create new roles to attract highly capable leaders from other sectors in a way that standalone schools cannot.

They can also nurture great talent by establishing a clear pipeline to leadership for teachers and non-teaching staff.

MSOs shoulder principals’ administrative burdens so principals are free to focus on instructional leadership. They give principals help during acute crises, and provide stability to schools experiencing leadership turnover.

3.1.1 Multi-school organisations can extend the impact of one-of-a-kind leaders

MSOs can harvest the untapped potential of a country’s best school leaders. The emergence of MSOs in England and New York has helped a crop of transformative leaders flourish; leaders whose influence is now reaching many more students than it otherwise could.

For example, Grattan researchers interviewed a passionate special education and disability coordinator who worked across their MSO’s 17 schools to improve inclusion. We met numerous expert teachers who had taken promotions to lead improvement in their subject area across multiple schools, refining curriculum materials and running professional development for teachers. And we spoke to a former school business manager who had taken a promotion to head up ‘back-office’ functions across several schools.

The MSO structure not only affords new opportunities to extend the impact of exceptional leaders already working in schools. It also helps groups of schools to attract and nurture great leaders. MSOs create new roles, such as chief financial officers and chief people officers. These roles create opportunities to bring in high-calibre candidates from outside the school sector.81

Because they run groups of schools, MSOs can also establish a clear talent pipeline. Leaders in the MSOs Grattan visited had opportunities to shadow colleagues in other schools, receive mentoring and undertake secondments, and participate in multi-year development programs and principal residencies. This stands in stark contrast to Australia, where school leaders are often ill-prepared for the role.82

MSO leadership development programs are aligned to the MSO’s blueprint for excellent schooling. This gives emerging leaders the chance to go deep on how to implement and adapt the blueprint in their school. Box 3 explains the approach, and careful succession planning, of Dixons Academies Trust in England’s north.

Box 3: Attracting and nurturing talent at Dixons Academies Trust

Founded in 1990, Dixons runs 17 schools in England’s north, 10 of which are turnaround schools. Almost 40 per cent of Dixons’ 14,000 students are disadvantaged.a

Dixons’ mission is to ‘challenge educational and social disadvantage in the north’.b It sees ‘investing in the professional growth of colleagues’ as one of the best ways to accomplish that mission.c

Dixons has to think carefully about how it attracts and develops great teachers and support staff because, as one leader told us: ‘working in the north, we don’t have the luxury of appealing to a great glut of talent – we have to nurture our own’.

In designing its talent strategy, Dixons sought to make the most of the MSO structure. Its aspiration was for staff to be able to chart their career at Dixons, from graduate to leader. A leader explained:

The multi-academy trust model allows multiple opportunities in multiple different schools. For example, the principal of Dixons Cottingley Academy began with us as a newly qualified teacher.

Dixons’ approach starts with recruiting staff aligned to its three values: work hard, be good, be nice. Dixons’ central team plays a significant role in expanding the candidate pool. That team has designed and overseen a strategy that includes building a careers website and running social media campaigns, which help fill more than 300 roles across the MSO each year.

Dixons has been able to attract high-calibre candidates in a way stand-alone schools could not. It has, for example, an experienced chief people officer who previously led employee development and engagement at Aldi.

Dixons’ size and alignment on what effective practice looks like creates development opportunities for staff. New staff get whole-of-organisation onboarding, and all staff – leaders, teachers, and non-teaching staff – are entitled to frequent coaching.

Dixons has established a Centre for Growth, through which it pools resources to offer professional development, such as a two-year leadership program for anyone new to senior leadership (about 30 staff members a year). One leader told us that an advantage of Dixons running its own program is that it can ‘get into the detail of implementation’, including training senior leaders in the specific aspects of leadership at Dixons:

Rather than each school working out what to do for professional development, Dixons can design something with deep credibility and ensure the most effective practitioner has the greatest impact across the organisation.

This creates job opportunities that aren’t available elsewhere. As one leader, who now runs professional development across Dixons, explained:

Before, if I wanted to influence professional growth across multiple schools, I would have had to leave my job. The benefits are clear. Dixons has a secure pipeline of talented leaders. Dixons Trinity Academy, which opened in 2012, has had 10 of its teachers go on to become principals.

a. Grattan analysis of Department for Education (2023c).

b. Dixons Academies Trust (n.d.).

c. Dixons OpenSource (2021).

3.1.2 Multi-school organisations can reduce the burden on principals and support them in crises

An MSO’s central team can alleviate the pressure on principals by providing practical support in areas such as human resources, financial planning, compliance and risk, estates management, and information technology.

Principals across the MSOs we studied described how this support allowed them to spend more time visiting classrooms, working directly with their teachers, and engaging more deeply with their local community.

This was the case at St Charles Borromeo, in Harlem, New York, one of 11 Catholic schools operated by Partnership Schools. St Charles Borromeo’s student population is highly diverse. Before joining Partnership Schools in 2018, St Charles Borromeo had poor results and declining enrolments. With the help of Partnership Schools, its enrolment has more than doubled. Results in the 2023 New York State Tests show that – despite disruption from the pandemic and welcoming many new students – the school is heading in the right direction.83

A key factor behind its success was how principals could rely on Partnership Schools’ central team for support. St Charles Borromeo’s principal, who had been at the school before it joined the MSO, explained:

As the principal, I now get support. I’m no longer in charge of the boiler. If there is a flood, somebody else takes care of it. I’m not having to be HR, and facilities, and the vision, and academics, and the culture – I’m not stretched that thin any more. I have a working knowledge of everything that’s going on, but I don’t have my hands in everything. That’s one of the many blessings of being part of Partnership Schools.

Box 4 describes in more detail how Partnership Schools’ central team empowers principals.

Principals across the MSOs we visited stressed that support from their MSO’s head office not only freed them up to focus on teaching and learning, it also helped them with the ‘things that keep leaders up at night’.

We heard several examples of principals confronted with hard issues – such as acute student behavioural problems, a difficult complaint from a parent, or a challenging employee-relations issue – and how being in an MSO meant there were always specialists on-hand who knew their school’s context and understood the MSO’s blueprint for running an effective school. Because they worked for the same organisation as the principals – and had shared an understanding of what it takes to run an effective school – these specialists were motivated to find a workable solution to complex challenges. This meant they avoided ’bouncing’ issues back to the school and took responsibility for the consequences of a decision (like accepting that introducing a new behaviour policy may result in an initial increase in parent complaints).

Principals frequently cited the pandemic as an example of a crisis in which their MSO’s support was critical.84 The English MSO United Learning, for example, distributed laptops to students, had technology specialists help schools pivot to teaching online, and distilled the emerging health advice for schools. A leader at United Learning told us:

Scale and capacity are crucial, and during COVID it was visible in all sorts of ways. There were people who were actually thinking, ‘What’s going to work with this new way of teaching? What are the curriculum changes that we need to do this?’ They produced lots of video lessons and made sure that we had the resources in place.

Box 4: The practical support principals get at Partnership Schools

At Partnership Schools in New York, principals can count on shoulder-to-shoulder support from a central team. That team does the legwork on tasks that would otherwise consume the time principals have to coach teachers, lead professional development, and engage with the school community.

The role of Partnership Schools’ central team has shifted as the MSO matured and responded to emerging priorities (such as the COVID-19 pandemic). When Grattan visited, key areas of back-office support included:

∙ budgeting and finance

∙ payroll

∙ aspects of talent acquisition (including writing job advertisements, screening applicants, and writing contracts)

∙ aspects of professional development (induction, curriculum workshops, training for non-teaching staff and leaders)

∙ student enrolment, high school placement, and scholarships

∙ some aspects of purchasing (e.g. curriculum materials)

∙ estates and building management

∙ reporting to and liaising with key stakeholders (e.g. the Catholic Diocese, City of New York, and philanthropists).

This support is tailored to Partnership Schools’ priorities and the needs of principals and schools. As one principal put it:

Each school is different and so the support we get is not a plug-and-play model.

On teacher recruitment, for example, some principals might lean heavily on the central team’s support, while others might decide to be closely involved in all stages of the process, including screening incoming applications.

Principals told Grattan that they felt empowered by this approach. One principal explained that she valued ‘getting to make the day-to-day decisions and being the vision carrier, while the central team takes care of all the ticky-tacky stuff’.

The principal summarised the benefits of this approach:

Being free of these operational things allows me to be in the classroom more and to be more present with the community.

Another principal explained how the central team’s practical support gave her more time to coach teachers, one-on-one: something she was very passionate about. Time saved on administrative work enabled her to help out with lesson plans, observe more classes, and provide regular feedback.

Teachers also noticed the change. A teacher, who had been at their school for 26 years, said:

One change is I actually get to see more of my principal. She was always busy with other things, but now I’m getting more of her time to go over lessons.

3.1.3 Multi-school organisations can provide stability when there is a change of principal

Principal turnover can cause significant instability for schools, especially disadvantaged schools where turnover is more frequent.85 It can also be a major challenge for school improvement, which requires sustained effort.86

MSOs can help reduce this instability. The MSOs Grattan visited were committed to institutional longevity and maintaining a through-line between successive principals. Incoming principals did not have to start from scratch, and could be inducted into the MSO and get support from the MSO’s central leadership team.

Dixons Cottingley Academy in England is a prime example. A teacher who had been at the school for 27 years told us:

We’ve gone through lots of change. We had lots of problems with multiple principals coming and going, which created massive instability. When Dixons came in, the change was almost overnight and lots of those initial problems were solved through stability.

Dixons Cottingley Academy has had three principals since it joined Dixons in 2018. These leadership changes occurred because, as the school stabilised, its leaders were redeployed to add capacity to other Dixons turnaround schools. Dixons Cottingley Academy staff told us that, despite the turnover, there was a clear through-line between successive principals.

3.2 Multi-school organisations can enrich the job of teaching

MSOs can also enhance teachers’ effectiveness and sense of professional fulfilment. Thanks to their size and alignment on what effective teaching entails, MSOs can equip teachers with resources that make the job more manageable and reduce the isolation that specialist staff sometimes feel. MSOs’ size also enables them to run relevant, hands-on training, and their multi-school structure creates richer career paths for teachers and non-teaching staff.

3.2.1 Multi-school organisations can give teachers practical support to do their jobs

MSOs help teachers be more effective by equipping them with the tools they need for effective teaching.

Each of the MSOs Grattan visited had high-quality curriculum materials and assessments that teachers could adapt and adopt. Teachers Grattan spoke to said having these materials meant they could focus on tailoring instruction to the students in their class.

One teacher at Partnership Schools in New York said the central team ‘gives us what we need – everything is right there’. Box 5 provides further details on the curriculum support teachers receive at Partnership Schools.

Teachers who were the only teacher at their school for a particular subject emphasised to Grattan the benefits of sharing the curriculum planning load across schools. One teacher at Dixons Trinity Academy spoke of the confidence she gained from being one of several Relationships, Sex, and Health Education (RSHE) teachers within the MSO:

It’s been invaluable to have Dixons’ support. The government guidance is, for example, that by the end of Year 11 all students need to know about contraception, and that needs to be taught in an age-appropriate manner in Years 7, 8, 9, and 10. And that’s all it says. As the sole person in charge of it at a school, that’s quite daunting, because you need to get it right.

Being able to have a meeting with 12 other professionals from Dixons just means you’ve got so much more confidence that you’re doing it right. And sharing actual resources – like ‘this is what we used in Year 9 to teach this topic’ – means you don’t have to plan it all yourself.

Box 5: Adopting high-quality curriculum materials across all Partnership Schools has improved teaching

When Partnership Schools was granted control of its seven New York schools, ensuring consistency and quality of curriculum across all schools was a top priority. The Partnership’s Vice President of Academics told us: ‘We think of curriculum as our key lever for changing outcomes at scale.

One principal said that, before Partnerships Schools arrived, choices of curriculum materials often came down to which vendor ‘was the best salesperson’, and the quality of curriculum planning varied across each school. Teachers across the organisation’s schools now use shared curriculum materials and follow a common pacing guide.

Partnership Schools has sought out externally developed materials that are rigorous and at grade-level. Once the materials are selected, the curriculum team in Partnership Schools’ head office develops supporting resources (such as pacing guides and supplementary questions), and runs organisation-wide professional development (sometimes bringing in curriculum-specific experts) to help teachers to adapt and use the materials in their classrooms.

Without common curriculum materials this coordinated support would not be possible. The MSO model helps, because individual schools don’t have the capacity to do this kind of work. As one Partnership Schools principal told us:

Unless you’re in the weeds, you don’t know. Principals would purchase a Math program without a solid rationale. By contrast, a central office researching the curriculum can dissect it and provide resources to go along with it. For example, our network team created exam-style questions for each unit in Math.

This takes a load off curriculum leaders in schools too. Now, a central curriculum specialist paces out the curriculum from kindergarten to Year 8, in each subject for all schools. Previously, curriculum leaders in each school would have duplicated this work.

For teachers, the common curriculum gives them a shared foundation and means that meetings can focus on the specifics of how to improve teaching practice. One teacher told us:

When we chat, we’re all at the same level. We can chat about a particular chapter we’re at. Partnership Schools has brought in a cohesiveness that allows us to talk to teachers outside our building.

Another teacher said:

The pacing guide that we follow means that all Partnership Schools’ teachers are at the same point. We can say, ‘I did it this way and it worked; I did it this way and it didn’t work’.

Now, common curriculum materials are a key part of Partnership Schools’ improvement strategy. One leader told us that if a school wants to join the Partnership, adopting common curriculum materials is a ‘non-negotiable’ and the ‘first order of business’.

3.2.2 Multi-school organisations can improve professional development and career progression

MSOs can offer teachers and non-teaching staff bespoke training, career opportunities, and pay progression that a single school – with its limited staff roster and budget – cannot.87 In the MSOs Grattan visited, teachers could plan out their entire career – from trainee teacher through to school leader.88

These career pathways are possible through the secondment and shadowing opportunities frequently offered by MSOs (see Section 3.1.1), particularly ones that are geographically concentrated.89 Analysis of England’s teacher workforce database showed that teachers were about 1.3 times more likely to be promoted if they worked in a large multi-academy trust.90

Students also stand to benefit from the ways MSO manage their teaching workforce. While research in the US finds that teachers typically shift to more advantaged settings when they change schools,91 one study found that teachers working in England’s multi-academy trusts tend to change to schools with more disadvantaged students.92

3.3 Multi-school organisations can expand opportunities for students

The MSO structure enables more students to benefit from the best classroom practice occurring across the MSO’s group of schools. And an MSO’s size helps them to provide students with specialist support and school experiences that are difficult for stand-alone schools to offer.

3.3.1 Multi-school organisations can enrich the academic experience for students

The MSOs Grattan visited lived by the mantra ‘every lesson counts’.

United Learning, England’s largest multi-academy trust with 97 schools spread nationally, takes seriously its mission to ensure that each of the 2,290 school days students have in their 12 years of school are filled with rich learning opportunities.

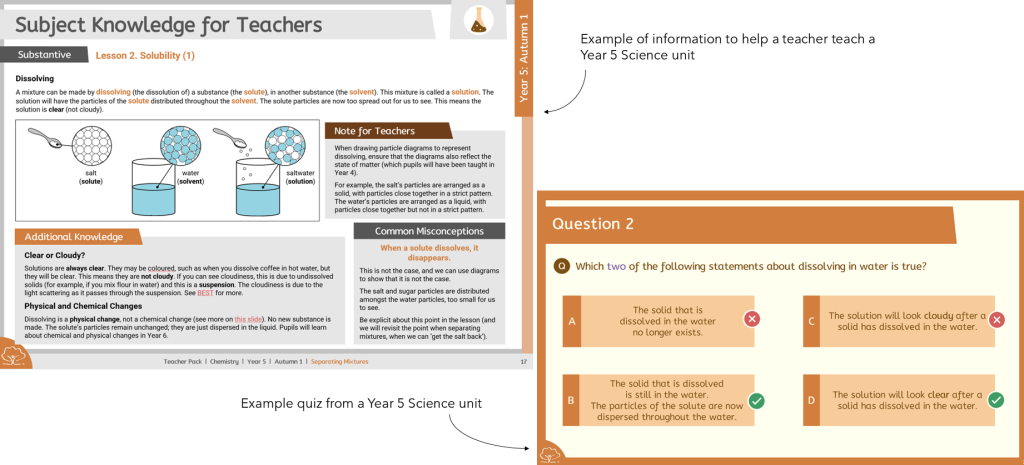

United Learning has developed curriculum materials for use across its schools, including teacher guidance packs, quizzes and assessments, and classroom resources (including activity booklets and PowerPoint slides like those shown in Figure 3.1).

United Learning has carefully planned the curriculum so that students develop deep, broad, and interconnected knowledge as they move through school. For example, students learn about Islam in Year 3 Religion and Worldviews, before studying the early Islamic civilisation in Year 4 History; they study food chains in Science at the same time as investigating the effects of over-fishing in Geography; and they use knowledge of forced migration, learnt in Geography, when learning in Art about artists such as Auerbach.

This kind of sophisticated curriculum planning is out of reach for most stand-alone schools. United Learning’s Director of Curriculum told us:

I don’t think individual schools can do the level of curriculum thinking that we can do. We have people who can spend time on it, and we can test it in our schools.

This type of curriculum planning is also tough for education departments. It requires a high level of coordination between schools (on, for example, instructional approaches, subject offerings, and timetables) which is easier in MSOs thanks to their ‘Goldilocks’ size and their authority to run a family of schools.

Figure 3.1: England’s largest MSO, United Learning, has developed high-quality curriculum materials

3.3.2 Multi-school organisations can make learning environments safer

MSOs can help spread effective approaches for creating safe and orderly learning environments.

When what is now called Dixons Cottingley Academy joined Dixons, disruptive student behaviour was a substantial challenge. An inspection of its predecessor school found ‘high levels of disruptive behaviour over time’ and that students ‘do not enjoy coming to school due to poor behaviour’.93

To turn this around, Dixons brought in leaders from its high-performing schools to implement tried-and-tested strategies to settle behaviour. Line-ups – which involve students assembling in lines at the bell to be escorted quietly to class – were a key strategy.

Line-ups help create calm transitions between break times and class, ensure lessons start on time with the whole class together, and reduce corridor noise for classes that have already started.

But line-ups are difficult to embed in a school – the strategy’s success hinges on the consistency that comes when all staff buy in and are on the same page. Dixons sent Cottingley Academy staff to other Dixons schools to see line-ups in action, and leaders who had implemented line-ups ran training sessions with the teachers.

The MSO model was crucial to the strategy’s success. A key factor was that 7 of the 10 staff in Dixons Cottingley Academy’s senior leadership team had worked at other Dixons schools, and seen line-ups work in practice. This meant they knew what would help the strategy succeed, and what might derail it. Today, Dixons Cottingley Academy leaders help other schools implement line-ups and improve behaviour.

One Dixons Cottingley Academy teacher told us:

People in senior leadership positions fully believed in the mission. That’s what the teachers needed: a leader who’s not flimsy and like, ‘I hope this works’, but instead like, ‘I’ve seen this work – this is what we’re doing’. The current principal came from another Dixons school. Being a part of Dixons means that you can take someone who’s already seen it work and can come in with that mentality.

Used well, the MSO structure can also provide more structured support for students after an acute behavioural incident. In Australian schools, students who seriously misbehave may remain on school grounds but not attend class (an ‘in-school’ suspension) or be sent home for several days (a regular suspension).94 Some MSOs Grattan visited offer alternatives that aren’t as disruptive to students’ learning but still deter students from serious misbehaviour (see Box 6).

Box 6: Improving student behaviour at Hurlingham Academy

Before joining United Learning, student achievement at Hurlingham Academy (Fulham, London) was in the bottom 20 per cent nationally, and challenging behaviour was a big problem.a

After joining, the school adopted strategies suggested by United Learning to minimise disruptions and maximise learning time. For example, students who seriously misbehave in class may be moved to a separate room to complete lessons under supervision. There they keep up with what classmates are learning thanks to United Learning’s bank of pre-recorded lessons. This approach would be near-impossible for a stand-alone school.

Being part of an MSO also enables ‘managed moves’, where students who persistently behave unsafely are sent temporarily to a nearby school. This offers students a fresh slate and supervised time away from negative influences. Managed moves can happen between stand-alone schools, but the MSO model means coordination is easier and learning is less disrupted because the schools follow a similar curriculum.

With United Learning’s support, the hard work Hurlingham Academy put in to improve behaviour is paying off. It is now in the top 4 per cent of schools by value-add to students’ achievement.b A recent inspection found that:

Pupils are respectful and attentive during class. They appreciate the clear and consistent behaviour systems in place. This means lesson time is not lost due to low-level disruption.c

Now the principal is spreading success further, leading two nearby United Learning turnaround schools as an executive principal.

a. FulhamSW6 (2015).

b. Grattan analysis of Department for Education (2023c).

c. Ofsted (2023d, p. 2).

3.3.3 Multi-school organisations have the capacity to provide students with specialised support

Grattan’s case study MSOs made use of their organisational heft to give students the support they need.

KIPP NYC Public Schools, for example, has hired student support specialists to work across its 18 schools.

In this New York-based MSO, more than 1,500 students (about 20 per cent) have specialised learning needs and are on an individual education plan. To support these students, KIPP NYC Public Schools has a shared services team that works across its schools and includes two school psychologists, two directors of social work, and four experts in literacy and numeracy intervention.

The psychologists and social workers help schools improve their whole-school well-being model, provide more intensive support for challenging individual student cases, and lend a hand with paperwork (such as behaviour support plans or compliance-related matters required by the city’s department of education). The specialists support about four schools each and are in each school at least fortnightly (or weekly in the case of the MSO’s elementary schools). They coach teachers, and adapt curriculum materials to better meet the needs of students requiring extra support.

The Director of the Student Support Services team – who has been in the organisation for 15 years – told us this support would not have been possible when he joined KIPP NYC Public Schools. The reason, he explained, was that ‘everyone was doing something different’ and there was little common practice between schools within the MSO. When he was appointed to coordinate special education, he ‘couldn’t review data because everyone had different datasets’. Now, with common systems, aligned curriculum materials, and a shared approach to screening students, the specialists in his team can provide targeted support. He compared this to the challenges large government departments face running many hundreds of schools, where ‘there are just too many schools to do this role with any level of impact’.

Box 7 explains how Star Academies also made use of the MSO structure to support students with special educational needs.

Box 7: How being a multi-school organisation helps Star Academies support students with special education needs

Star Academies in England has used its size to benefit the 1 in 7 students in its schools who have an identified special educational need.

The aim of Star’s multi-pronged strategy – called All Stars Succeed – is for all students to be taught the full Star curriculum, so they develop ‘the knowledge and cultural capital needed to succeed in life’.a

Star has adaptive instructional strategies for teachers to use to support students with additional needs. One example is ‘turn-and-talk’, in which students discuss a question in pairs before sharing back to the class. A suggested adaptation is to provide students with speaking frames and sentence-starters, to help them speak in pairs confidently and fluently.b These strategies benefit all students, but especially students with speech, language, and communication needs.