Published at The Conversation, Wednesday 12 December

School leavers across Australia are about to get their ATAR (Australian Tertiary Admission Rank). In the coming weeks, they will get a chance to update their university course preferences.

Most students attend university to improve their job prospects. But less than half of surveyed students believe they had enough information when they chose their course.

Here are three things prospective university students should keep in mind when finalising their preferences.

1. Drop-out rates

About one in five school leavers who start university will not complete a degree within nine years – and they generally earn less than their peers who graduate.

A Grattan Institute report released in April showed people who study part-time are much more likely to drop out than full-time students. Course choice is also important. Among students with similar characteristics, those studying health or education are less likely to drop out than those studying IT, engineering, science, or humanities.

Surveys of people who consider dropping out show engineering and IT students are often dissatisfied with the teaching and cite a lack of interest in their course. Science students are more likely to consider leaving because of poor employment prospects. This is rarely a reason cited by health and education students.

2. Early-career employment

Health and education bachelor-degree graduates have strong employment prospects. A Grattan report released in September found about 80% of health and education graduates were in a full-time jobs four months after finishing university. And they continue to do well during their early career (from their mid-20s to mid-30s). The share of women in this age range in full-time jobs is generally lower than men because many women leave work to have children.

Only 60% of science graduates who were looking for a full-time job found one within four months of finishing their degree. While this is partly because more science graduates continue studying, their poor job prospects persist into their early career. Some 66% of male and 50% of female science graduates in their mid-20s to mid-30s have a full-time job. Employment outcomes for other disciplines are shown below.

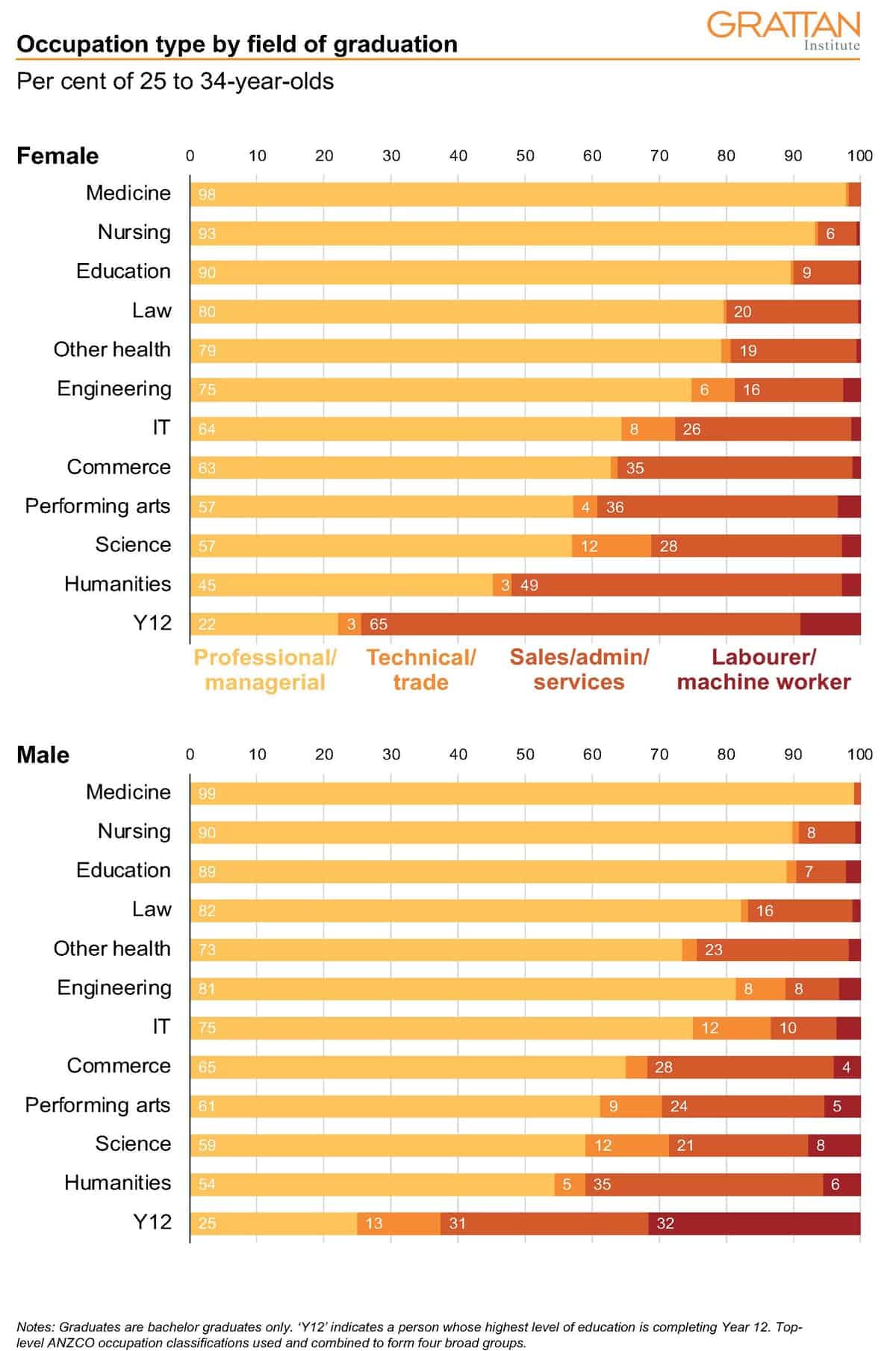

Having a job is one thing. Having a job that uses the skills developed at university is another. About 80% of employed early-career engineering and law graduates have a professional or managerial job. The figure for early-career nursing and education graduates is even better.

Getting a professional job is more difficult for graduates in generalist fields – humanities, commerce and science – and their prospects have declined since the Global Financial Crisis. Fewer than 60% of employed early-career male science graduates have a professional job. Female humanities graduates who have a job are more likely to work in sales or services than in professional occupations. Figures for other disciplines are shown below.

3. Lifetime earnings

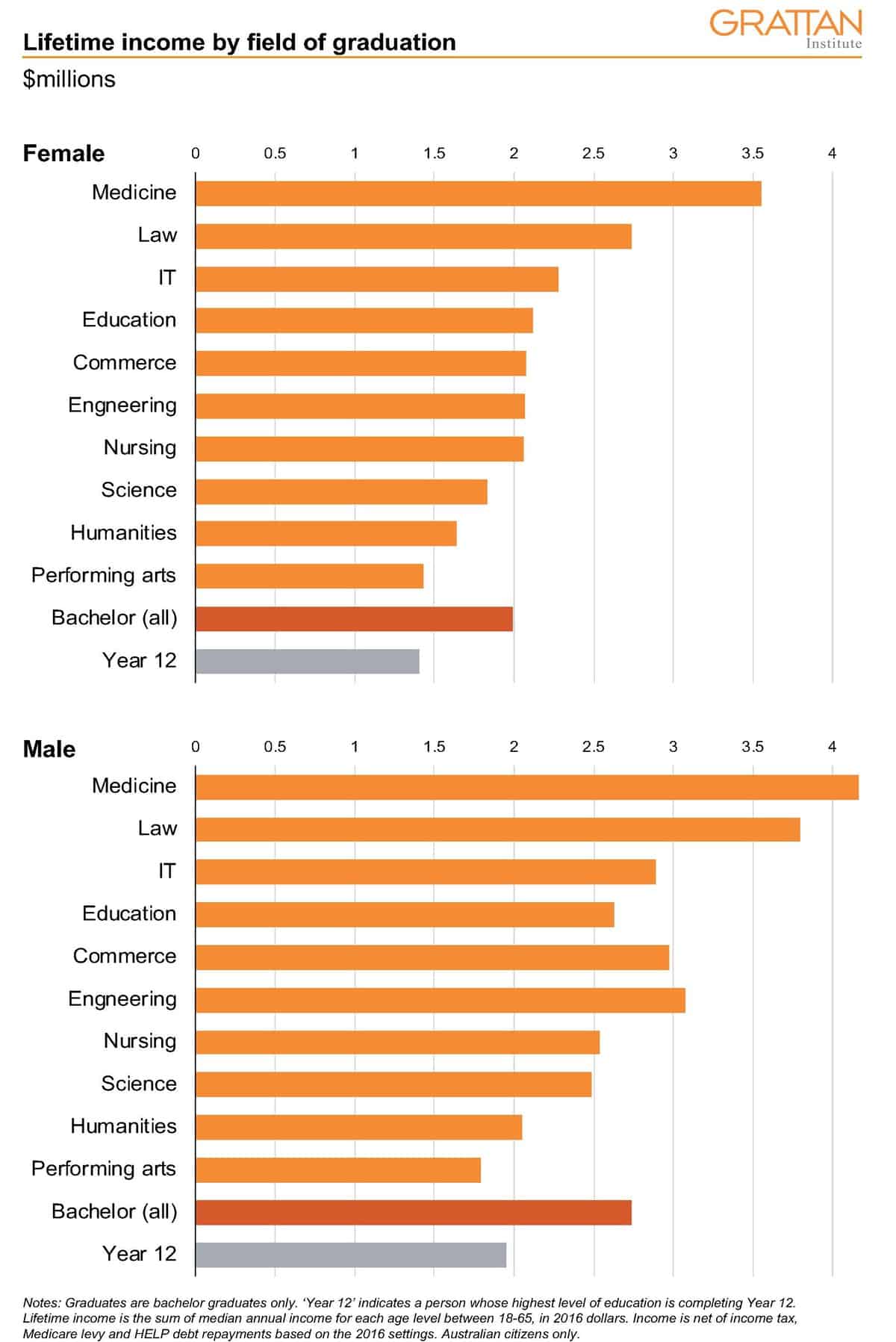

In terms of pay, commerce graduates typically have a slow start but can expect to earn above-average income over their lifetime – A$2.1 million for women and A$3 million for men.

Because nurses and teachers have flatter pay scales, men in nursing or education have lower-than-average lifetime earnings (about A$2.5 million). But their flexible working conditions make it easier for women with children to work in these fields. The average female nursing or education graduate can expect to earn A$2.1 million over their lifetime – more than the average female graduate.

Law and engineering graduates have much stronger lifetime earnings prospects than humanities and science graduates.

A 2014 Grattan Institute report found graduates of some universities tended to earn more over their lifetime than graduates of others, but the variation between universities was not as large as variation between fields of education.

A final word of advice

Students should look beyond course names to explore course content. That way they may be able to improve their employment prospects while still studying in a field that interests them. This information can be found on each university’s web page.

For example, students who like science should consider health courses. Health students spend about 25% of their first year studying science subjects – and they have better chances of securing a job that uses their qualification.

While choosing preferences is only one of the many steps students will take in their higher education journey, getting this right is important. The better choices they make now, the sooner students can realise their career goals.