Published in The New Daily, 20 November 2020

After months of speculation, the federal government’s Retirement Income Review has finally been made public.

The report, led by former senior bureaucrat Mike Callaghan, didn’t make recommendations, but its findings speak for themselves.

So, what have we learnt?

1. Most Australians can expect a comfortable retirement

At the core of the report is a good news story: Most retirees today appear financially comfortable in their retirement, and most workers today can expect the same when they retire.

The Review points out that surveys show retirees generally have higher levels of financial satisfaction and lower rates of financial stress than working-age Australians. And the Age Pension keeps low-income retirees out of poverty, provided they own their own homes.

Workers today can look forward to a standard of living in retirement that’s on par with their standard of living while working, and often higher.

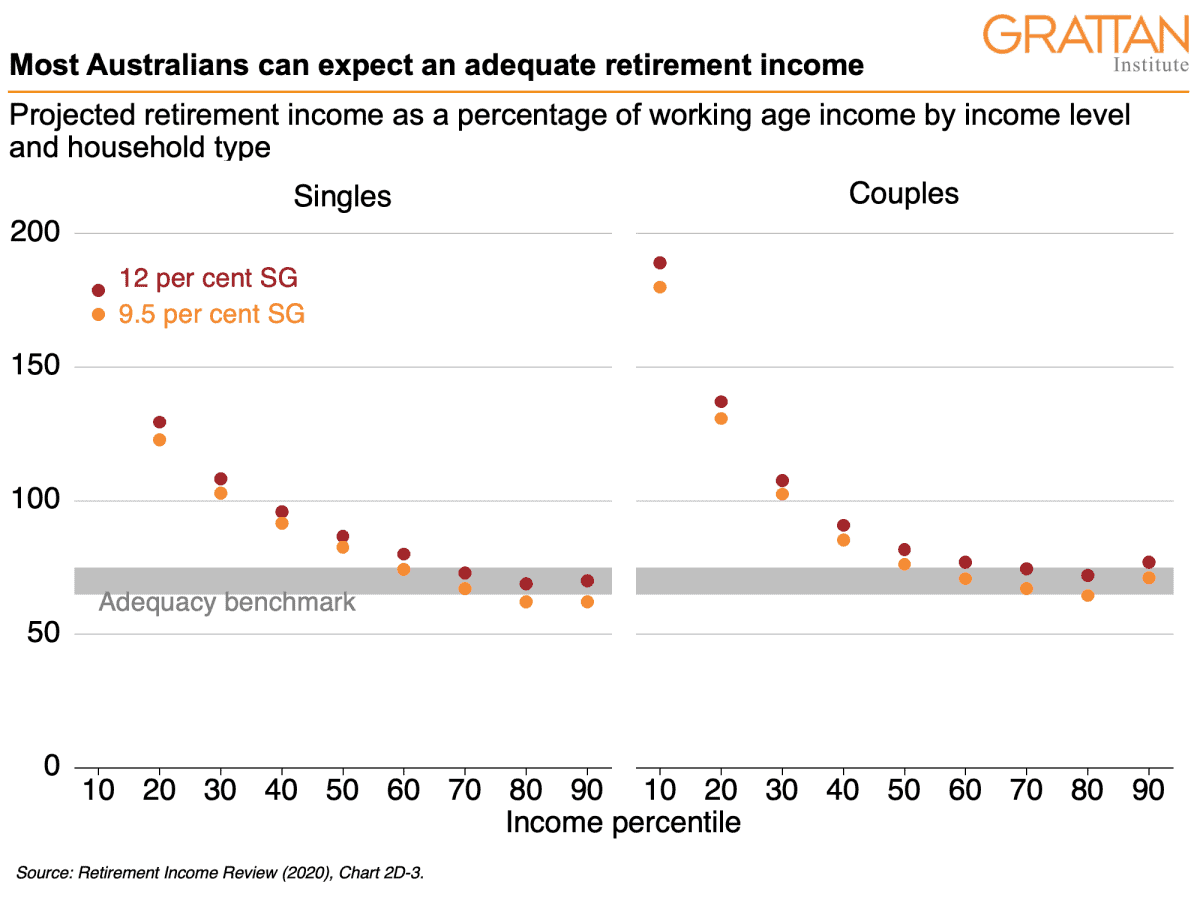

The Review defines an “adequate” retirement income as 65-to-75 per cent of workers’ pre-retirement, post-tax, earnings. And the Review’s modelling, consistent with Grattan Institute’s past research, shows that most Australians can expect to meet or beat that benchmark.

The typical single worker can expect to replace 88 per cent of their pre-retirement earnings, and the typical couple 82 per cent. Even most Australians who work part time or have broken work histories will achieve the benchmark.

One clear implication of the Review is that the already-legislated increases in compulsory super contributions, from 9.5 per cent of wages to 12 per cent, should be abandoned.

More compulsory super would force many Australians to save for a higher living standard in retirement than they have while working.

2. Higher super will mean lower growth in wages

Defenders of higher compulsory super often argue the legislated increase is the only guaranteed path to a pay rise after years of mediocre wages growth.

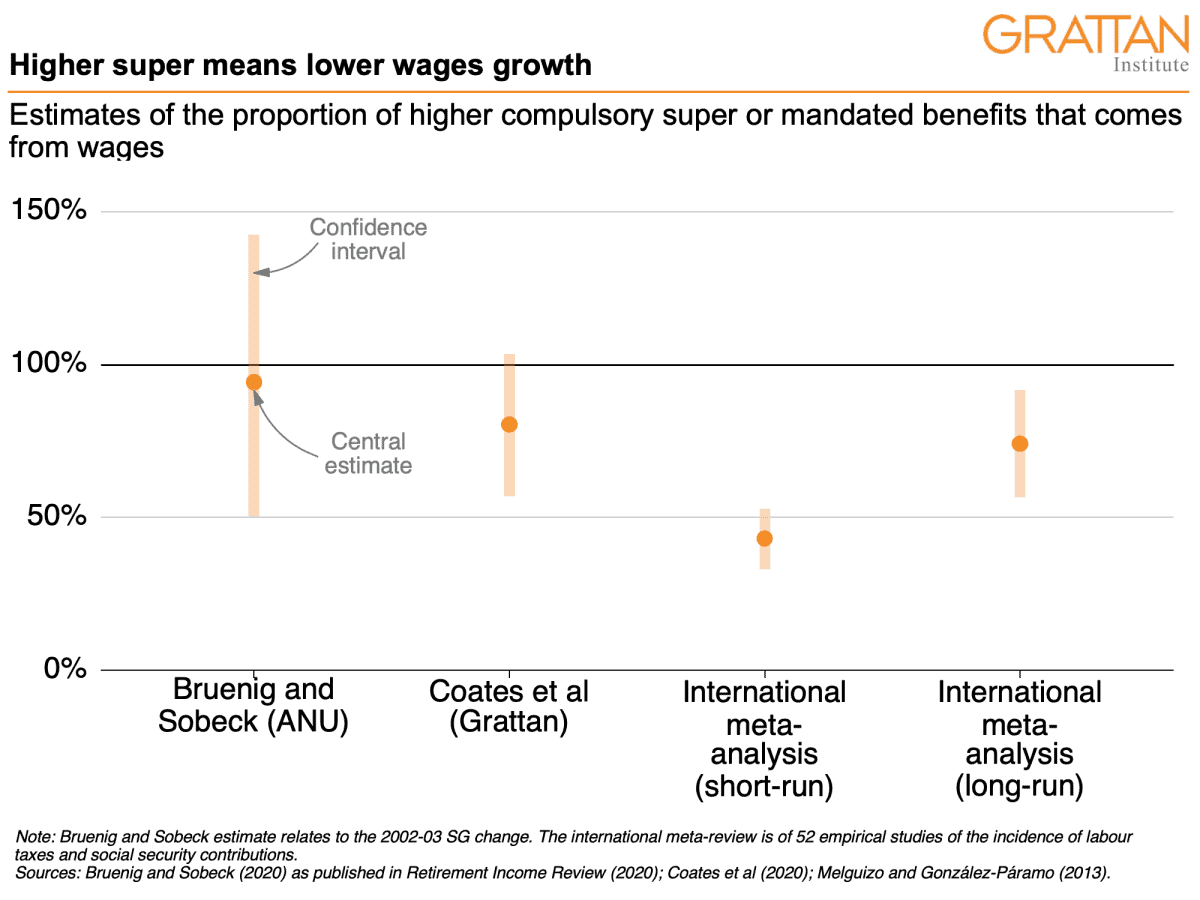

But the Review shows that while employers might hand over the cheque for super, workers ultimately pay the cost via lower growth in their wages.

New analysis from researchers at Australian National University, commissioned by the Review, found that workers bear at least 71 per cent, and in some cases more than 100 per cent, of the cost of higher compulsory super via lower growth in wages.

The researchers also found that the effect of super on wages has grown, not shrunk, over time.

3. Higher super costs the government more than it saves

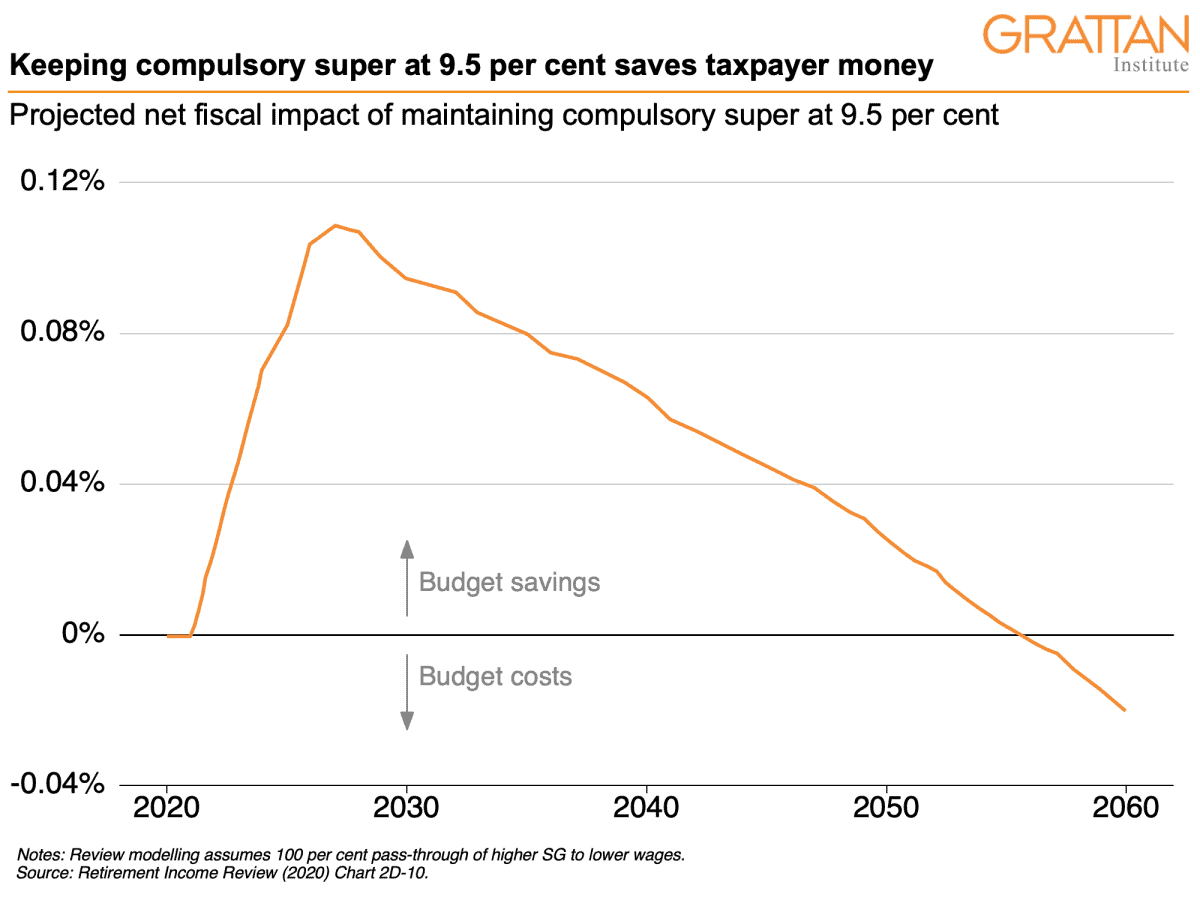

The Review also debunks the myth that boosting compulsory super would lighten the budgetary burden of an ageing population.

Modelling done for the Review shows that lifting compulsory super from 9.5 per cent to 12 per cent would cost taxpayers more in super tax breaks than it would save in reduced Age Pension spending until 2055.

And even then, there would be 35 years of accumulated debt to pay back before taxpayers ended up ahead.

Of course, this arithmetic could change if the government curbed Australia’s overly generous super tax breaks.

But super tax breaks would need to be cut dramatically – perhaps by $10 billion a year out of about $30 billion – before compulsory super would start to save the budget real money anytime soon. For now, that prospect remains remote.

4. The pension is here to stay

Some people fear the Age Pension is going to become unsustainably expensive for the government. The Review has a clear message for them: Chill out.

The amount that the government spends on the pension has been stable over the past 20 years and the Review projects that it’s likely to fall a little, as a share of the economy, over the next 40 years.

Back in 2001, the Age Pension cost 2.2 per cent of GDP. It’s now about 2.5 per cent of GDP.

The Review projects the cost of the pension will fall to 2.3 per cent of GDP by 2060.

If the super guarantee stays at its current level rather than going up, the Review projects that the pension will cost 2.4 per cent of GDP in 2060.

5. Renters are in trouble

But our retirement income system isn’t delivering for everyone. Renters – particularly low-income renters – are at real risk of having an inadequate retirement income.

The Review found that about 60 per cent of single retirees who rent their home are in poverty, compared to about 10 per cent of single home-owner retirees. And that number will only grow as home ownership falls.

The solution is obvious: The government should boost the rate of Commonwealth Rent Assistance by enough to pull renters out of poverty.

In our submission to the review, we recommended a 40 per cent increase. But the review shows that even that wouldn’t be enough to meaningfully close the gap in retirement incomes between renters and home owners.

Perhaps that’s the biggest takeaway from the Review: The government needs to do something dramatic to ensure the growing number of retirees who rent can avoid poverty in retirement.