A good tax system raises the revenue to fund quality public services. A better tax system does that more efficiently, fairly, and in a way that is simple to comply with and administer. Australia can do better on all three fronts.

Above all, we need a tax system that is helping us and not hindering us to adapt to a changing world.

The longer we wait, the more ill-fitting our tax system is going to be, and the harder this task gets.

1. Tax is a powerful policy lever

If we want to build economic prosperity for all Australians, then tax is a powerful lever to do so.

Done well, tax enables the type of society that builds human capital and stable institutions that all of us – people and businesses – draw benefit from. Tax is also one of the policy tools we have to shape the economy.

Our economic settings form part of the institutional make-up of Australian society: our laws, spending, and taxes build capabilities and incentives for education, work, and innovation. If we ensure that economic gains are not concentrated among the few, but are broadly distributed across the population, then that supports greater trust and stability, which in turns supports investment, innovation… and higher living standards.1Sathanapally (2024).

That is the virtuous cycle that Australia can and should strive for.

A country can raise revenue in better or worse ways. Crucially, tax policy settings cannot remain set in stone. They must adapt to the world we find ourselves in, and where the future is headed.

If our tax system isn’t match-fit for the real world, then it drags on our ability to achieve our collective policy objectives. And over time, if the system fails to work for young people, or to tackle the known challenges that people expect their governments to act on, then that erodes trust in institutions and in our very democracy.2Younger people generally report lower trust in government than older Australians: O’Donnell, Guan, and Prentice (2024), Australian Election Study (2022). Trust in government is influenced by a range of factors including perceptions of government competencies and values, and cultural, economic, and political factors such as whether people feel they have a say in government decisions: OECD (2025).

That is the downwards spiral we must avoid.

So a mature democracy must keep tax reform on the table.

Given where Australia stands today, reforming our tax mix (moving from worse to better ways of raising revenue) is a real opportunity to boost productivity and lift economic growth.

2. Adapting to a changing world

But this isn’t just about a better tax system today: adapting our tax system is a necessary part of meeting the big challenges facing us in the coming decades.

Let me underscore: tax is a policy lever. Like spending, like legislation, like regulation.

Done well, our tax system aligns to the big shifts that we know are coming.

These shifts are profound, and we shouldn’t underestimate them.

I’ll start with ageing, because it has a very direct connection to both tax and spending.

Today, 8 per cent of Australia’s population is over 75.375 years and older at June 2024: Australian Bureau of Statistics (2025). That group receives the highest level of social benefits (health care, aged care) of any age group.4Tax and Transfer Policy Institute (2025). By 2050, they will comprise 12.4 per cent of the population.5Medium fertility, life expectancy, and net overseas migration assumptions: Australian Bureau of Statistics (2023).

We are already seeing the impacts in the workforce as the Baby Boomers retire, on our housing needs as households get older and smaller, our health system, where the growth in demand is unrelenting, and on both paid and unpaid social assistance, or care.

At the same time, more and more Australians look set to retire with significant savings and housing assets, and many retirees are still net savers after they retire.6Coates et al (2025).

And then there are the twin shifts of

- Climate change, with its profound impacts in terms of extreme weather events; and

- Decarbonisation, with its tremendous opportunity for Australia to be an energy and resources powerhouse, if we can manage the substantial infrastructure investment and economic transformation ahead;

And geopolitical and technological change loom large, as you will have discussed on day one, heralding disruption, but also creating the space for innovation and different opportunities for Australia as a stable, open, pluralist country.

If our tax system does not adapt to meet these changes, if this type of policy reform gets relegated to the too-hard basket and the system remains stuck: it can end up working against us.

The process we are part of today has already yielded many actionable ideas. But this process will also hopefully open the door to some of the bigger reforms that will necessarily take time to design and to build public understanding of why they are needed.

I would encourage us to think big and long-term: our national conversation about tax reform should be about how we sustain a high quality of life in this country for young people today and the generations that follow them, given the headwinds that confront us.

That ought to be the level of our ambition and the imperative for action. And we should not delay in taking available steps to get the tax system to do better, rather than waiting to remake it into something perfect.

3. Priorities for reform

To open the discussion, I see four broad ways in which we can improve our tax system.

Down the road, these are areas we could conceive of as packages of reform, but at a minimum, they are four opportunities that are too big to ignore.

The first is rebalancing our personal tax system. This is where there seems to be the greatest expert agreement on problems with the system, and clarity about solutions.

The second is improving taxation of businesses, to boost investment in productive activities, make the system less complex, and align business investment with the activities that we most need.

The third is making better use of pricing signals, to improve the efficiency of how we use our assets, such as roads, and to put us on the least-cost path to decarbonising our economy and adapting to extreme weather.

And the fourth is tackling the federal imbalance in our system, which I’ll argue is vital if we are to get to a tax mix that is more efficient, less volatile, and more likely to keep pace with Australia’s future needs.

4. Comparing Australia’s tax system to its peers

First, let’s have a look at how Australia sits in comparative terms.

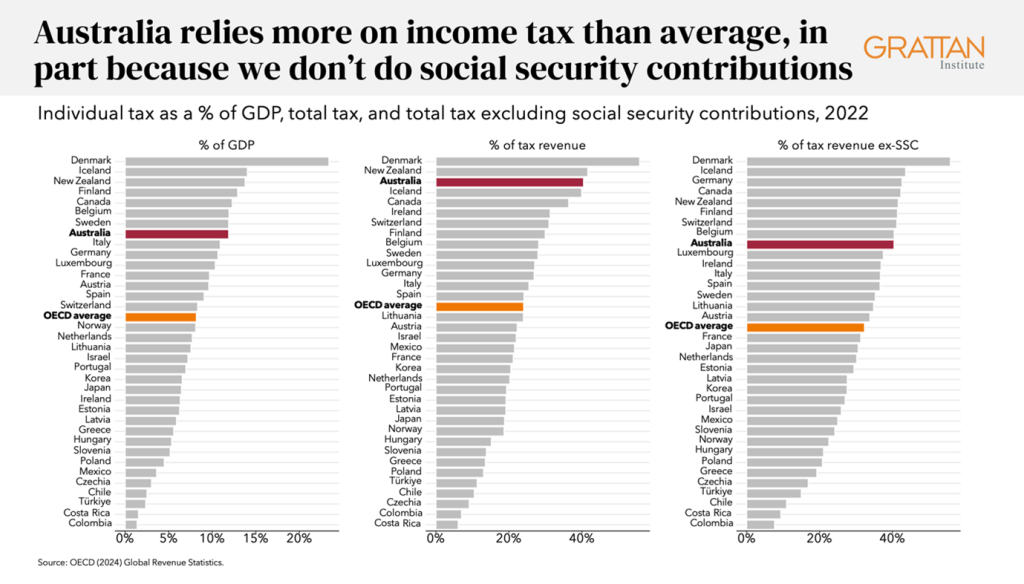

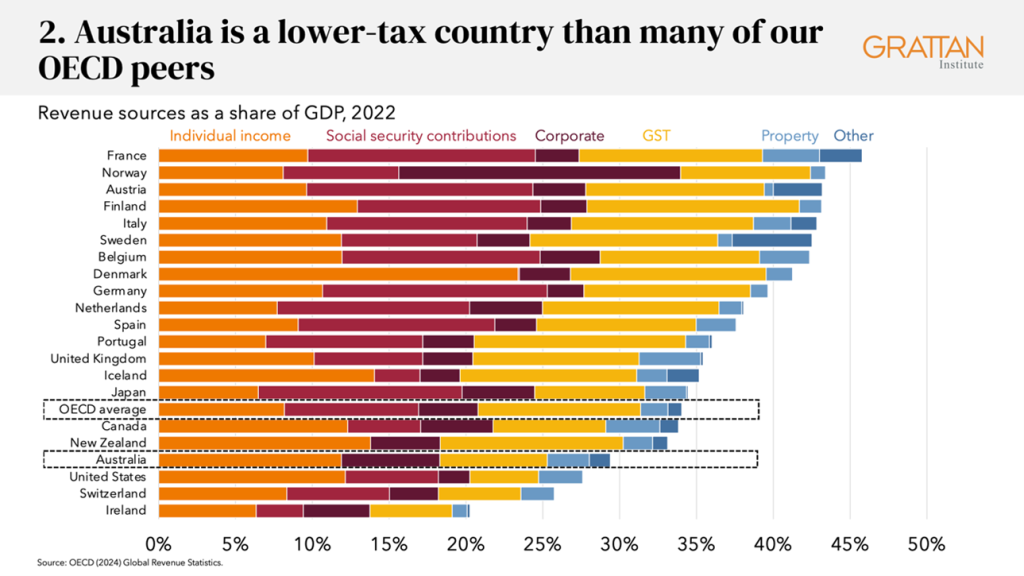

On Chart 2, you see Australia’s reliance on different taxes compared to many, not all, OECD countries.7Comparisons to other countries are made using the Global Revenue Statistics Database: OECD (2024).

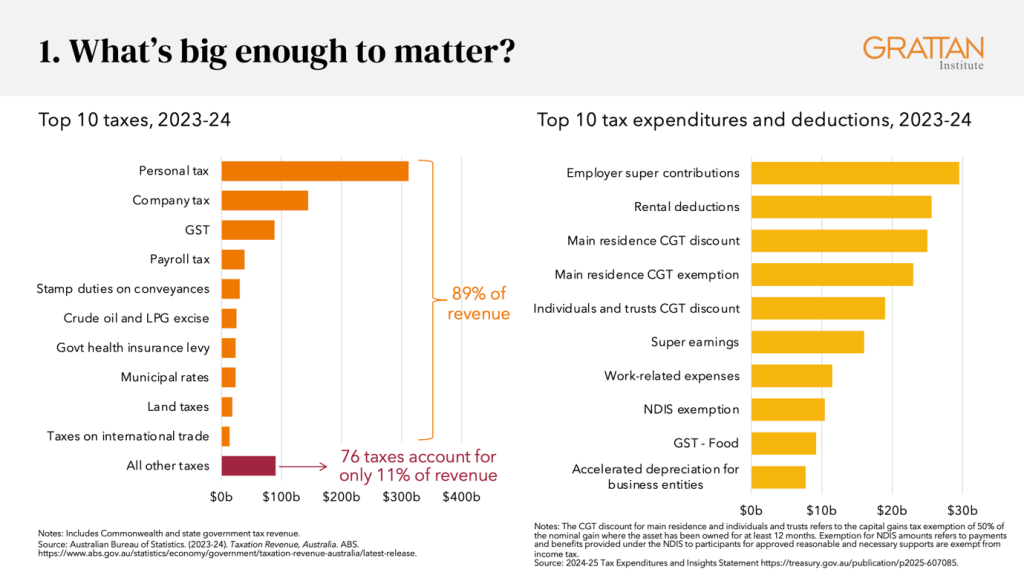

- Overall, Australia is a low-tax country relative to its peers, well below the OECD average. Revenue across all governments sits at 29.4 per cent of GDP; 24 per cent of that is federal revenue, and 3.2 per cent of that is the GST, which passes through to the states.

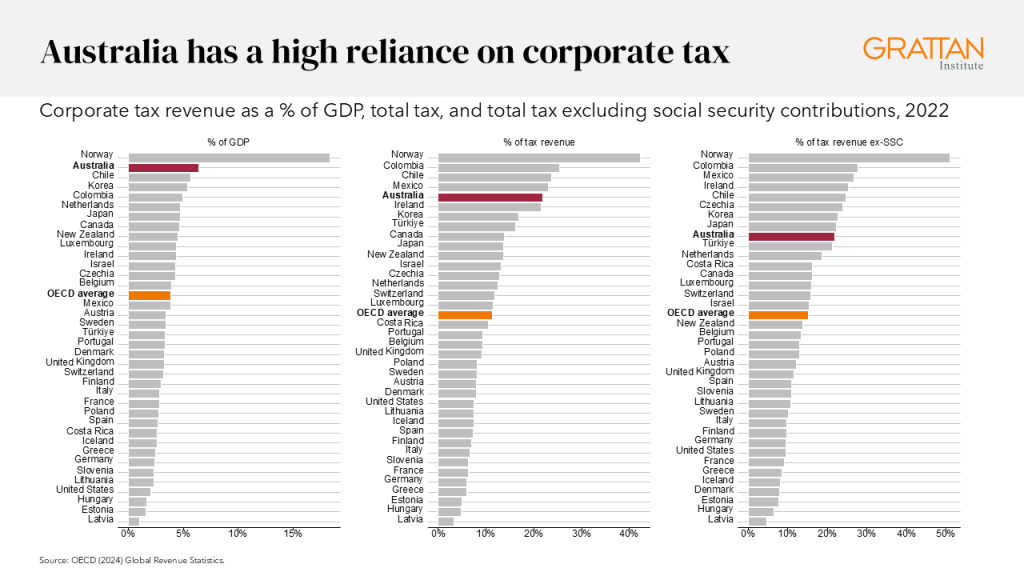

- Our total corporate tax take is high relative to our peers – in part artificially because of dividend imputation, and because we have a resources economy that can generate excess profits when commodity prices are high.8Stewart (2019); PBO (2024); Minifie et al (2017, p. 31).

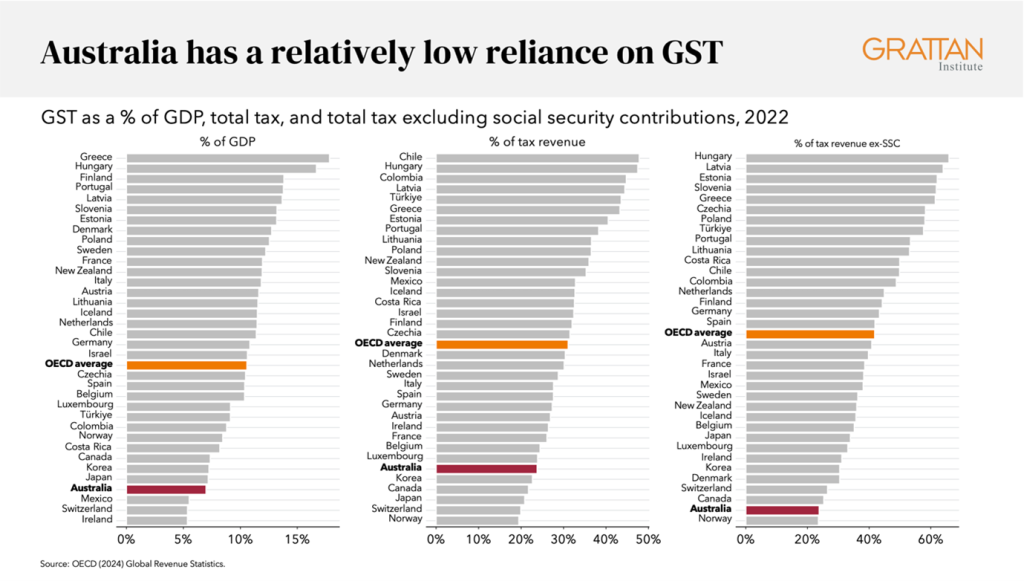

- Our GST is relatively low – this is a genuine point of difference. Its rate is low, but also the significant carve-outs for food, health, and education, mean that it has not kept pace with economic growth, so is smaller now than it was when introduced.9GST receipts averaged about 3.6 per cent of GDP through the 2000s; since 2021-2022, receipts have been steady at around 3.2 per cent of GDP: PBO (2025), 2025-26 Budget data, tables 1 and 6.

Australia does not separately levy social security contributions, which most OECD countries use to pay for unemployment benefits and pensions.10See OECD (2025). This muddies the comparisons. So I’ve provided a few different comparisons in an Appendix.

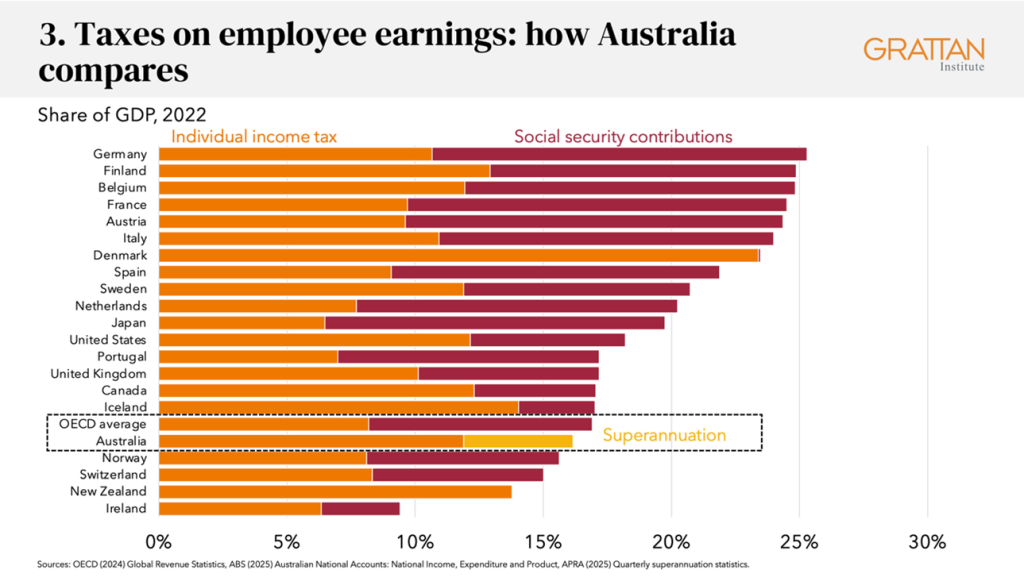

Chart 3 just shows you the extent of taxes on employee earnings – a truer comparison. It shows we aren’t onerous in terms of personal income tax in aggregate – and that is the case even if you add in superannuation, which is not a tax, but is compulsory saving.11Compulsory superannuation contributions were 4.3 per cent of GDP in 2022, the latest year of OECD data. This has risen to about 4.9 per cent in 2024. Voluntary contributions would add another 2-to-2.4 per cent of GDP but are excluded because they are voluntary. Grattan Institute analysis of APRA (2025) and ABS (2025).

5. Rebalancing our personal income system

The issue here isn’t how much personal income tax we collect, but the imbalanced way in which we do it.

How we treat different ways to make money matters in the signals it sends for education, skills development and choice of jobs, and how to structure one’s life and finances.

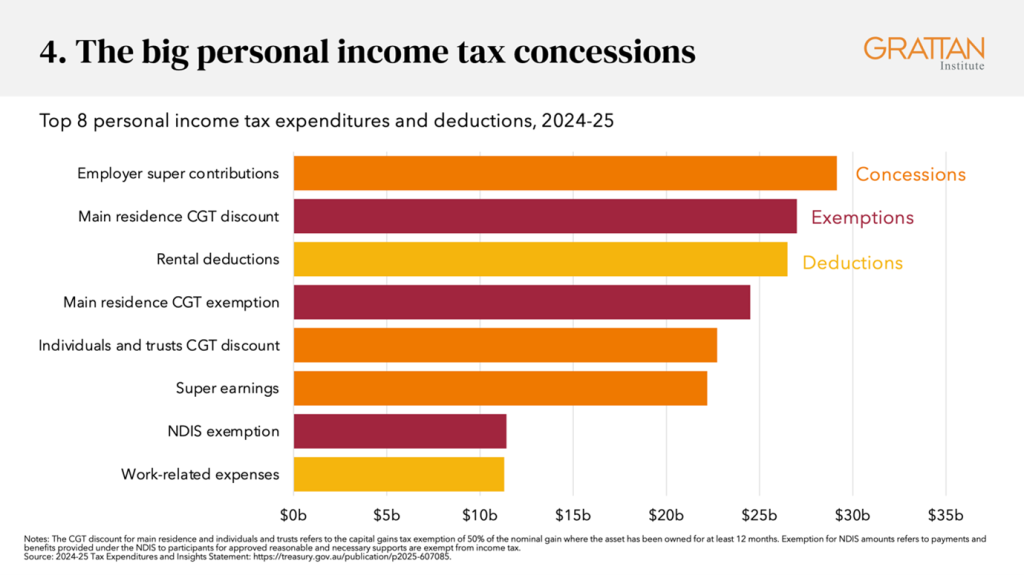

As it currently stands, wages and salaries from work are what we lean on most heavily in our tax system12In 2023-24, individual income tax accounted for about 52 per cent of tax revenue: PBO (2025), 2025-26 Budget data, table 6. Of this, the number of people paying tax, and the average tax paid, on salaries and wages is far higher than any other component: ATO (2025), table 5. … and alongside it, we have created very generous concessions for making your income almost any other way. These are set out on Chart 4.

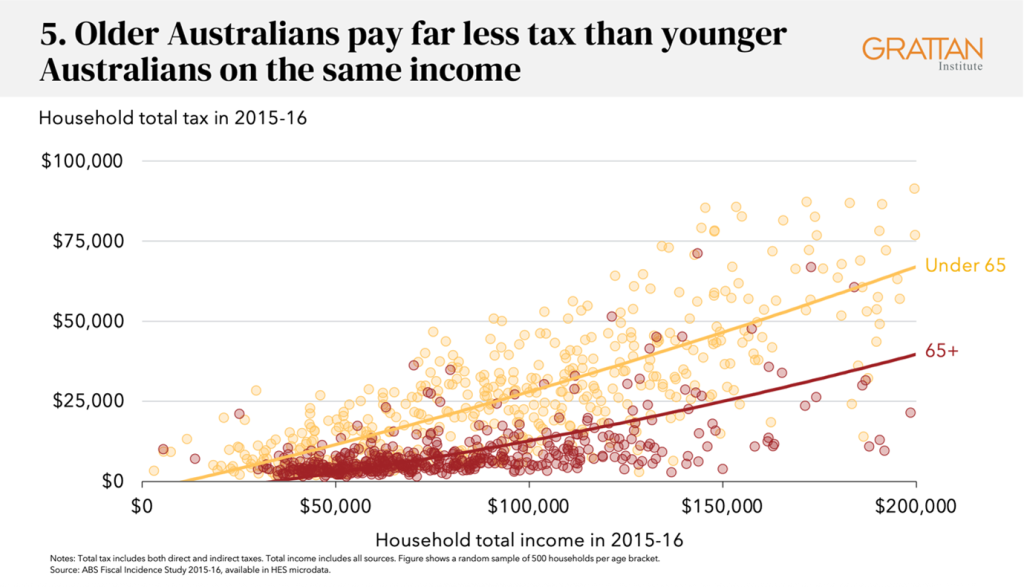

The end result is that Australia’s tax system treats households on the same income vastly differently – so it does poorly on a pretty vital element of the income tax system, referred to as horizontal equity.

The major driver of this inequality is the treatment of income in retirement, where superannuation earnings and withdrawals are not taxed over the age of 60. And so a retiree household, earning $100,000 per annum, can pay less than half of the tax of a working household with the identical income, purely on the basis of age.13Wood et al (2019, p. 37). Chart 5 shows this divergence.

But it isn’t just in the retirement phase: this inequity in tax treatment extends to incomes in working life as well, through the way we treat investment in housing, and the use of trusts and private companies.

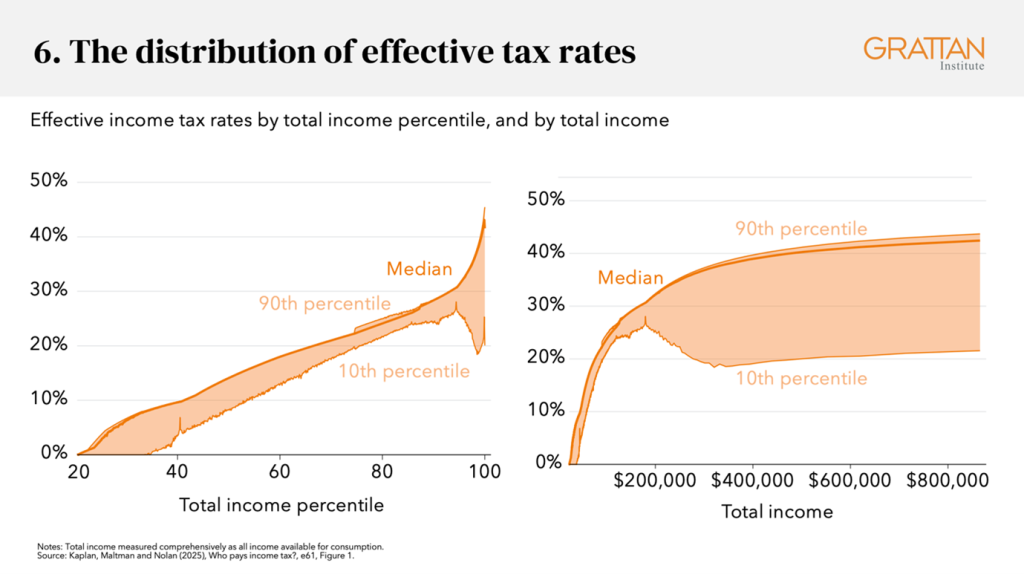

This is starkly evident in recent analysis by e61 (on Chart 6) using tax return data, showing that while 95 per cent of people pay similar tax rates for similar incomes, for the top 5 per cent, the amount of tax paid varies hugely, and indeed, people on very high incomes can end up facing lower rates than those on far lower incomes.14Kaplan et al (2025, Figure 1).

About half of this effect comes from the very generous tax discount for income from capital gains. And we know from previous research that deductions and trust income are key mechanisms to manipulate taxable income as well.15Breunig, Deutscher, and Hamilton (2022).

I imagine not much of this is surprising to you: these problems have been well-admired over the years. But they add up to a system replete with perverse incentives and unprincipled outcomes.

We know how to fix it. The solutions are legislative, and the power sits with the federal government. The problem has always been a political one: the noise that attends any suggestion that tax breaks be withdrawn. As a result, the dysfunction of this system has only worsened with time.

It can be fixed in pieces: reducing superannuation concessions so the system meets the policy objective of saving for a decent retirement, rather than being a tax shelter; introducing at least a low tax rate on earnings in retirement; reducing the capital gains discount; reforms to family trusts.

Or the repair could be systematic: a dual-income system that brings consistency to how we treat different types of savings.

And then, there is the other side of the scales: how the tax and transfer system affects the majority of working-age people.

Today, among the OECD, our average tax rate on average full-time wages is relatively low,16The average tax rate for the average wage earner was around 22 per cent in 2023-24 (Australian Government (2025)), and the average tax rate across all workers was about 26.1 per cent (PBO (2024)). These are expected to be a bit over 1 percentage-point lower in 2027-28 due to recent tax cuts. The tax wedge, or the tax share of worker costs, is below the OECD average: OECD (2025). though our top marginal rate of 45 per cent does kick in comparatively early.17OECD (2025). Australia’s top marginal tax rate kicks in at about 1.7 times the average wage, the 11th highest in the OECD. This is below the median OECD country where the top rate kicks in at 3.1 times the average wage. Australia’s top marginal tax rate is equal to the median in the OECD. But it is also true that, even with the tax cuts of recent years, the average tax rate for all workers is higher than at any time through the 2000s and 2010s.

If we do nothing, our default fiscal repair strategy is to increasingly rely on taxes on employment, and in fact worse: to rely on inequitable taxes on employment, given the opportunities for wealthier Australians to minimise their taxes.

Addressing the treatment of income from wealth gives us far better options for the future: income tax in total can keep pace with our underlying needs and expectations without increasing the burden on a smaller, working-age population.

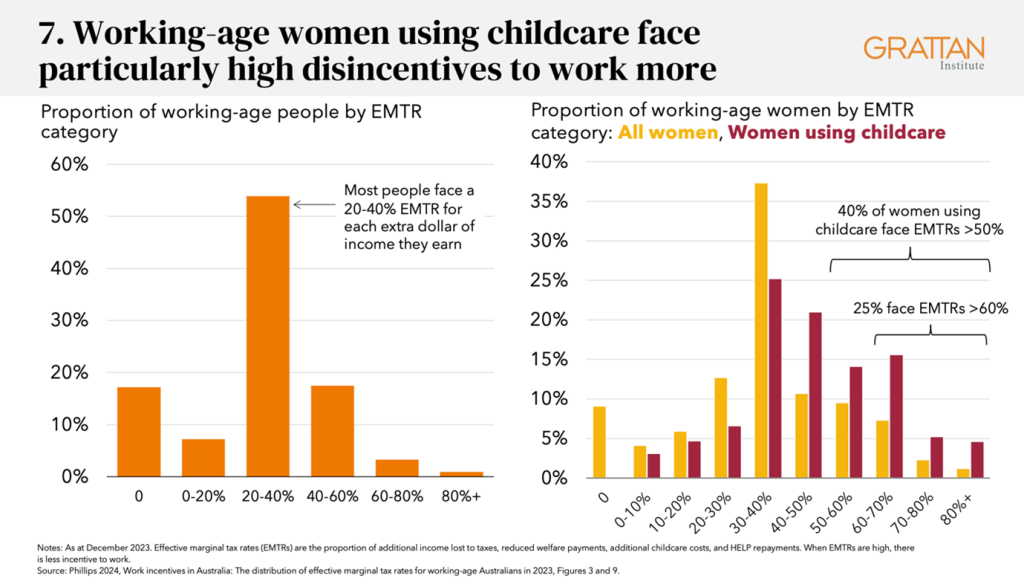

If you think a top tax rate of 45 per cent is high,18Australia’s top marginal tax rate is 45 per cent for income over $190,000. The 2 per cent Medicare Levy sits on top of this. spare a thought for the two out of five women using childcare who face effective marginal tax rates above 50 per cent (Chart 7).19Phillips (2024) Figure 9. Australia has unusually high levels of women working part-time, despite their level of education and skill.20Using the OECD definition of less than 30 hours per week, 32.5 per cent of employed women in Australia work part-time, compared to an OECD average of 22.8 per cent: OECD (2025). By the ABS definition of less than 35 hours per week, 43 per cent of Australian women work part-time: ABS (2025). At the same time, Australian women are highly educated – 57 per cent of women aged 25-64 have a tertiary degree, behind only Canada and Japan: Sathanapally et al (2025, p. 23). It’s not just a matter of the days or hours they work – it is the workplaces they end up working in, and it is the lower career progression and skills development that they experience, which is a type of labour market scarring with lifelong consequences. And if we care about productivity, we should care about that.

But for working households with children, it is the tax and transfer system acting together that matters – and the best way forward may not necessarily be through changing tax rates, it may be through changing the design of family payments,21For example, see: Rondinel, Kalb, and Stewart (2025). and improving access to affordable, quality childcare.22Sathanapally et al (2025, pp. 23-25) and Wood, Griffiths, and Emslie (2020).

6. Improving business taxation

We will need a substantial volume of business investment to realise the opportunities to reshape Australia’s economy and make it more resilient in the decades ahead.

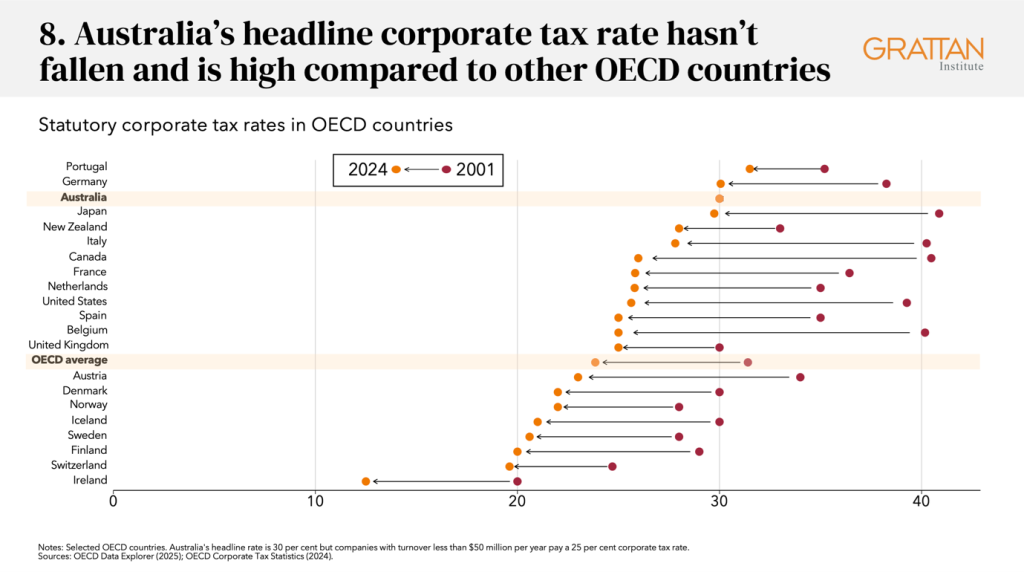

On Chart 8, you can see that 25 years ago, Australia’s corporate tax rate was below the OECD average. But the world has changed, and we are now one of the highest.

At present, our company tax does two things in roughly equal measure:23This is the analysis of Chris Murphy, who did the economic modelling for the Productivity Commission interim report, Creating a more dynamic and resilient economy, and the Henry review. Murphy (2025, Table 6) found that 46 per cent of the current company tax base is on normal returns to capital, and 54 per cent is on economic rents. it taxes normal profits, which is economically damaging.24Productivity Commission (2025, p. 9); Murphy (2025, p. 6); Minifie et al (2017, p. 36). And it taxes immobile economic rents, mainly from mining and banking, which is an efficient way to raise revenue that would otherwise be excess profit.25Economic rents are profits that exceed the normal, risk-adjusted return to investment (Sobeck et al (2022, Appendix A)). Immobile economic rents occur from a specific location advantage that cannot be moved, for example the location of mineral deposits. See also: Productivity Commission (2025, p. 9); Murphy (2025, p. 9).

And that isn’t the only difficulty with our corporate tax system, with its bias towards debt financing, variations in effective rates across different investments, and unique system of dividend imputation.

This is why improving our corporate tax system is a genuinely tricky design question. There is no clear consensus either among experts or the business community on the fix. On my reading, the impact of corporate tax cuts on investment in Australia is likely to be modest.26There is international evidence that suggests potential for significant investment, but it is unclear that effect would follow in the Australian context, and the variability of effect is high. For example, Feld and Heckemeyer (2011) synthesised 45 studies on the impact of a host country’s tax rate on foreign direct investments, finding a positive effect on average, but a broad range of impacts including some that resulted in no change or a negative impact. More recent evidence from the large corporate tax cuts in the US in 2017 suggests there was an increase in investment, but it was insufficient to meet the enormous cost of the tax cuts to the US budget. For example, see Brookings (2025). Murphy’s modelling of the Productivity Commission’s proposed corporate tax reform package estimates that business investment will increase by a modest 1.4 per cent (Productivity Commission (2025, p. 72)). The evidence is that past investment allowances in Australia have likewise had only limited impact.27Win et al (2025). This makes it hard to justify the hefty price tags these changes come with. And in designing business taxation across the board: we should ensure that Australians share in the wealth that comes from exploiting our natural endowments.

The question I have is whether there is appetite to improve this system in a manner that is revenue neutral across business taxation as a whole – rather than funded through debt, spending cuts elsewhere, or tax increases elsewhere.

If the preference instead is for stability in design, and incremental changes, are there other, more immediate ways to make Australia more attractive, such as reducing the complexity of the taxation system, or reducing non-tax hurdles to investment?

7. Who’s afraid of a carbon price?

The third big reform is using pricing signals to drive productive investment.

Australia comprises a small population on a vast landmass. That fact alone drives productivity challenges for us that are different to other countries: in energy, in services, in transport. The scale of our per capita overheads makes it paramount for us to make the best possible use of our assets.

Effective pricing of externalities would help us do that better.

For example, replacing the fuel excise with road user and congestion-charging for vehicles is a way of using market signals to reduce damage and smooth time of road use.

Reforms in the last term priced carbon for one quarter of the economy. Building on this momentum can put us on a least-cost pathway to achieving net-zero emissions. This does not have to be a tax – it could be designed to raise revenue, or not.

When it comes to our exports of fossil fuels, however, the case for a redesign of taxation to actually raise some revenue is compelling.28Sathanapally et al (2025, p. 29). In the 2023-24 financial year, companies subject to the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax (PRRT) had assessable receipts (income against which PRRT liability is assessed) totalling $46.2 billion, but paid only $1.4 billion in PRRT, an effective tax rate of 3 per cent. In the 2000-01 financial year, the effective rate paid against assessable receipts was 22 per cent (ATO 2025, Table 5).

For one, the longer we leave this, the greater the chance we miss the boat entirely.

Second, there is a strong imperative to find a way to pay for the damage wrought by the physical consequences of climate change. Since the 2019-20 bushfires, natural disasters have cost the federal government alone $13.6 billion.29Sum of other purpose expenses for natural disaster relief (actual), financial years 2019-20 to 2023-24, Budget Paper 1. There is a high cost to adapting to climate change – and an even higher cost of failing to adapt, and neither are captured in the forward spending estimates right now. If not a carbon tax that raises revenue, or a greater share of the tremendous profits being made now on fossil fuels, how will we pay this mounting bill?

8. All roads lead to the GST

That brings me, finally, to the GST.

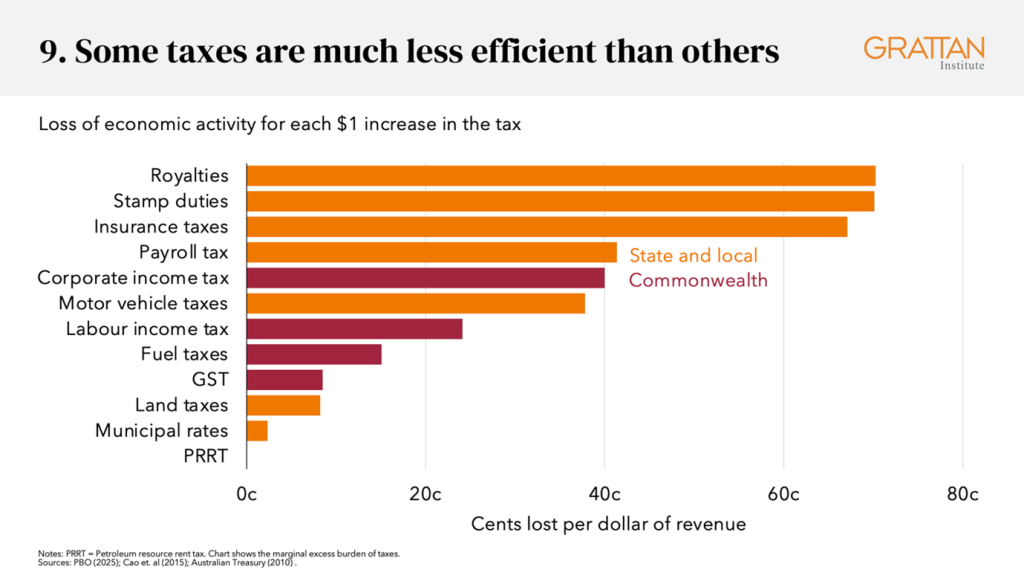

If we come back to the point at the start that you can boost productivity by switching your mix of taxes from more damaging to less damaging, then the clearest case in point is Australia’s relatively low reliance on the GST, which is a relatively efficient way to raise revenue.

Increasing the GST would hurt poorer households more, and that matters.30See Davidson (2025, p. 7). But it is possible to compensate people for these regressive effects and still raise revenue.31For example, see the Parliamentary Budget Office’s costing of Kate Chaney MP’s three proposed changes to the GST (PBO (2025)). Chart 9 sets out estimates of how economically damaging a range of taxes are.

The GST goes to the states, and is the only untied revenue they receive. The states’ other major sources of revenue are generally the worst taxes from an economic perspective. The states’ budget positions are more challenging in every case, bar Western Australia, than the federal budget.32PBO (2024).

A tax reform agenda that includes harmonising payroll tax across jurisdictions and moving from stamp duty to a broad-based land tax would have a bigger economic payoff than pretty much any other tax mix change.33Sathanapally et al (2025, pp. 56-57). But that it is hard to do, and for stamp duty, costly to transition.

The GST legislation passed in 1999 says that changes to the GST rate and base require all states to agree. As a matter of constitutional power, the federal Parliament could change that legislation. But as a matter of federal practice, consider whether the conversation around the GST ought to involve the states, to grapple with the reality that they have fewer choices, and that GST reform would be most powerful if it enabled tax reform at the state level.

9. Three ‘C’s to guide us

In late 2023, my predecessor at the Grattan Institute – some of you may know her – delivered a scholarly lecture on tax reform, asking if it was an impossible dream.34Wood (2023).

She identified that the first step for tax reform is to put it on the agenda.

Here we are.

And now it is here, we cannot be complacent about the opportunity.

Our tax system is not fit for the future we face. The longer we leave this, the harder it gets.

Our budget is not sustainable. We are burdening our children with unpaid bills and worse choices. And we are under-investing in some of the most cost-effective measures to support living standards and save money in future – for example, preventative health measures, a decent safety net, and resilience to climate risks.

We can however be confident in our ability to do better.

We are more than just a lucky country: Australia has done big social and economic reform before. If we look up and out – we can see that we are coming from a place of strength on many measures, not least our relative trust in government and in each other.35Sathanapally et al (2025, p. 94).

We have an opportunity to think bigger than overnight winners and losers, and beyond the short term; to take some practical steps forward.

Finally, compromise will be a necessary part of the task ahead.

The best reform is not the one most perfectly designed, but the one that actually happens.

It is too easy to torpedo change. The temptation for the media and vested interests is to amplify any conflict and flood the zone with bad analysis and hysteria. The fact that many of the better taxes are more noticeable to people, and the worse taxes are just politically easier, is fertile ground for a scare campaign.36Wood (2023).

Common ground is what people want and need from Australia’s leaders.

Today, can we get to a shared sense of priorities for reform?

I have suggested four broad directions, not the finer details of design. But today’s conversation isn’t about how many tax experts it takes to build an optimal tax system. It’s about asking what a better social compact would look like.

I’m not actually a scholar of tax. I studied the institutions of democracy, specifically: what it takes to get good, evidence-based public decisions, where principled disagreement can be reasonable and trade-offs unavoidable.

It takes four things, as it turns out: time (and we have time generously given today); good quality information (the data, the state of the evidence), a diversity of perspectives, and finally, an openness – to find that space for compromise, or to even change one’s mind.

So, let’s get started.

Appendix: International comparisons