Australia has a housing crisis. Australians are spending more of their incomes on housing than in the past. Poorer people are feeling the pinch most. Many low-income renters are living in poverty, and many more are suffering financial stress. Inequality is increasing, and more Australians are becoming homeless.

Australia’s social housing stock has stagnated

Social housing – where rents are typically capped at 25 per cent of tenants’ incomes – can make a big difference to the lives of vulnerable Australians. Australian evidence and international experience shows social housing substantially reduces tenants’ risk of homelessness.1

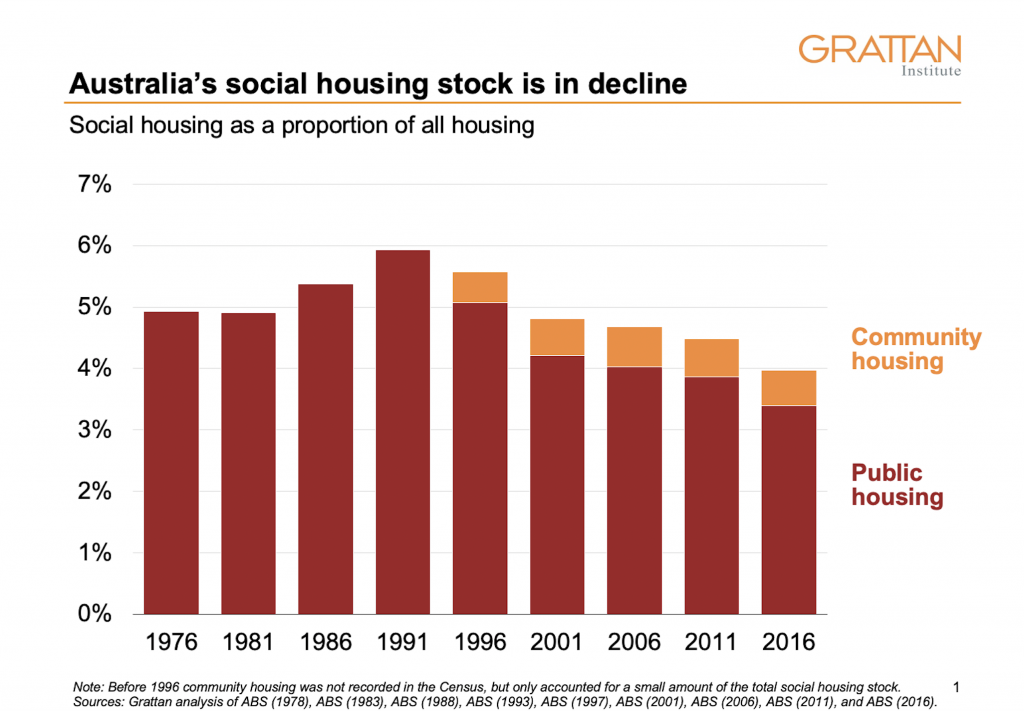

Yet the stock of social housing – currently around 430,000 dwellings – has barely grown in 20 years, while Australia’s population has increased by 33 per cent. About 6 per cent of housing in Australia was social in 1991. It’s now less than 4 per cent.

Most social housing tenants stay for more than five years. Australia’s stagnating social housing stock therefore means there is little ‘flow’ of social housing available for people whose lives take a big turn for the worse.2 The result is that a smaller proportion of Australians is living in social housing than in the past, and every year proportionally fewer social housing units become available for new tenants.

More poorer Australians are having to rent in the private market. The median low-income social renter pays 24 per cent of their income on rent, compared with 37 per cent for the typical low-income private renter.3

With fewer low-income Australians owning their home or living in social housing, their housing costs are rising. The bottom 20 per cent of households by income now spend 29 per cent of their income on housing on average, up from 22 per cent in 1995.

But boosting social housing won’t come cheap

Social housing is expensive because governments provide a big rental discount to vulnerable tenants.4 If governments were going to try to recoup these costs over time, as private landlords do, the rents they would need to charge would be higher than vulnerable residents can afford to pay.5

This means there is an ongoing ‘subsidy gap’ which can either be paid upfront (i.e. by writing off the net present value of the annual subsidy) or an annual basis by recognising that the social rents will fall short of the market rent for the home.6

In 2018, the annual subsidy gap payment was estimated at about $13,000, or around $15,000 in today’s dollars, although that varies substantially across Australia. The upfront subsidy gap is about $300,000, which can be covered via capital grants to community housing providers or state governments to expand public housing.7

The challenge for the federal government is how to pay for more social housing.

The Federal Government should establish a Social Housing Future Fund

The Federal Government should establish a Social Housing Future Fund, which could make regular capital grants to state governments and community housing providers.

The Federal Government already manages $247.8 billion in assets across six future funds to address long-term problems ranging from covering federal public servants’ superannuation entitlements to funding medical research.8

The endowments for existing federal future funds were typically raised from asset privatisations, explicit budget savings, and expected future budget surpluses.9 The endowment for a Social Housing Future Fund could be established by borrowing at today’s ultra-low interest rates and invested with the Future Fund Board of Guardians.10 Some states, including Victoria, NSW, and Queensland already operate social housing investment funds, in some cases financed by government borrowing.11

The value of the new federal Social Housing Future Fund should be maintained over time to keep pace with inflation, and the investment returns above the inflation rate used to fund capital grants for new social housing units, allocated via the National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation (NHFIC).12 Capital grants would be allocated via a competitive tender, with requirements for dwelling size and location, maximising the housing subsidies delivered to tenants.13

Such a fund could boost social housing with little or no hit to the federal government’s budget bottom line. Since the initial endowment is an investment, it wouldn’t appear on the underlying budget balance. Instead, only the annual returns on the fund, less debt interest costs and any capital grants allocated, would affect the budget balance each year. For example, the government could issue $20 billion in bonds, and invest it into the fund. The government would have to pay interest on the bonds but can generally earn higher returns on its investment.

Nor would establishing such a fund hurt the federal government’s balance sheet. An extra $20 billion in gross debt is small fry compared to the nearly $1 trillion in debt currently on issue, supported by about $500 billion a year in federal government revenues.14 What’s more, the increased debt would be offset by assets of equivalent value in the form of investments held by the Future Fund – in the form of stocks, bonds, and infrastructure holdings.

While the Fund would expose taxpayers to extra investment risk – the price of higher returns – the new fund would add less than one-tenth to total existing assets currently managed by the Future Fund.

How much social housing could a $20 billion Future Fund support?

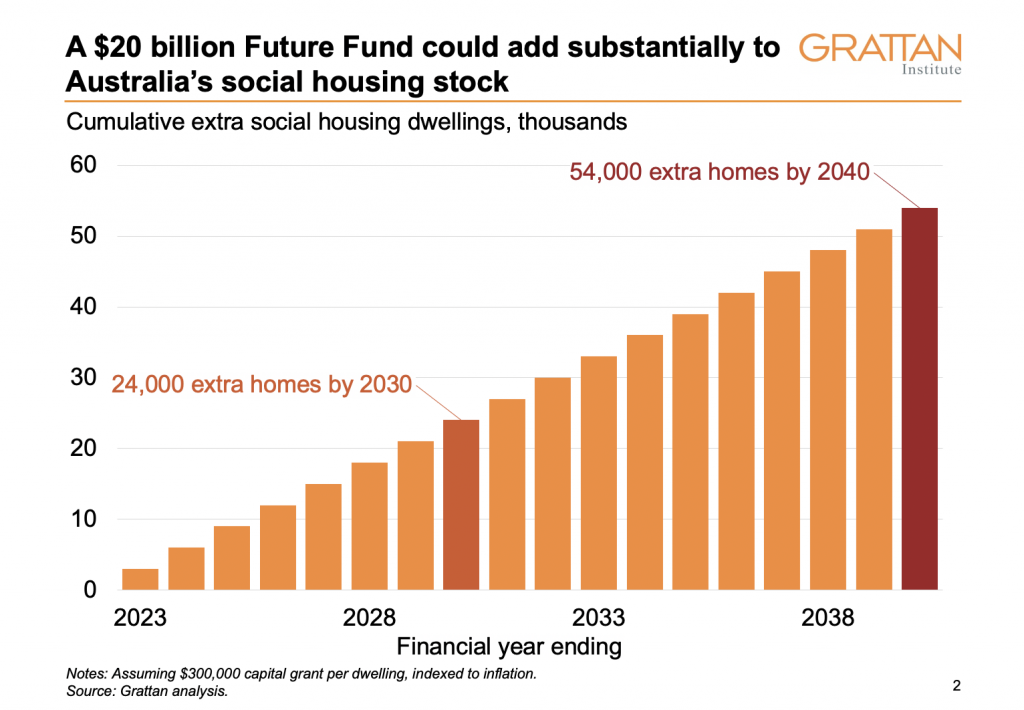

A $20 billion fund, with an investment mandate to target real (after-inflation) returns of 4-to-5 per cent, could over time provide a dividend averaging $900 million each year. Such a fund could deliver 3,000 extra social housing units a year in perpetuity, assuming capital grants of $300,000 per dwelling to cover the upfront subsidy gap.15 If commenced in 2022-23, the Future Fund could build 24,000 social housing dwellings by 2030, and 54,000 by 2040. Future governments could choose to top up the fund endowment, helping expand the social housing share of the national housing stock in future.

The direct financial cost to the federal government would be modest – about $400 million a year, or less than 0.1 per cent of federal government spending each year, in the form of interest costs on the outstanding debt.16 Alternatively, part of the return from the Future Fund could be used to cover these debt interest costs, leaving $500 million available each year to fund the construction of about 1,700 new social housing dwellings each year with no hit to the Government’s underlying cash balance.

Dragging the states to the table

The Morrison Government has been clear that it regards social housing as the responsibility of state governments. Yet the history of Australia’s federation shows that large social programs, from Medicare to the post-WW2 expansion of social housing, only succeed with federal support. This reflects Australia’s ‘vertical fiscal imbalance’: for every five dollars in taxes levied each year in Australia, the federal government collects four and the states only one.17

Nonetheless the Federal Government’s frustration with state inaction on social housing is not without some basis. In the decade after the last big federal social housing investment – the $6 billion Social Housing Initiative by the Rudd-Gillard governments which built 20,000 social homes during the Global Financial Crisis, and renovated thousands more – state investment in social housing has been anaemic. In the five years leading into COVID, the total stock of social housing increased by just 1,600 homes. Only in response to the COVID crisis have state governments adopted social housing construction programs as economic stimulus, notably the Big Housing Build in Victoria.

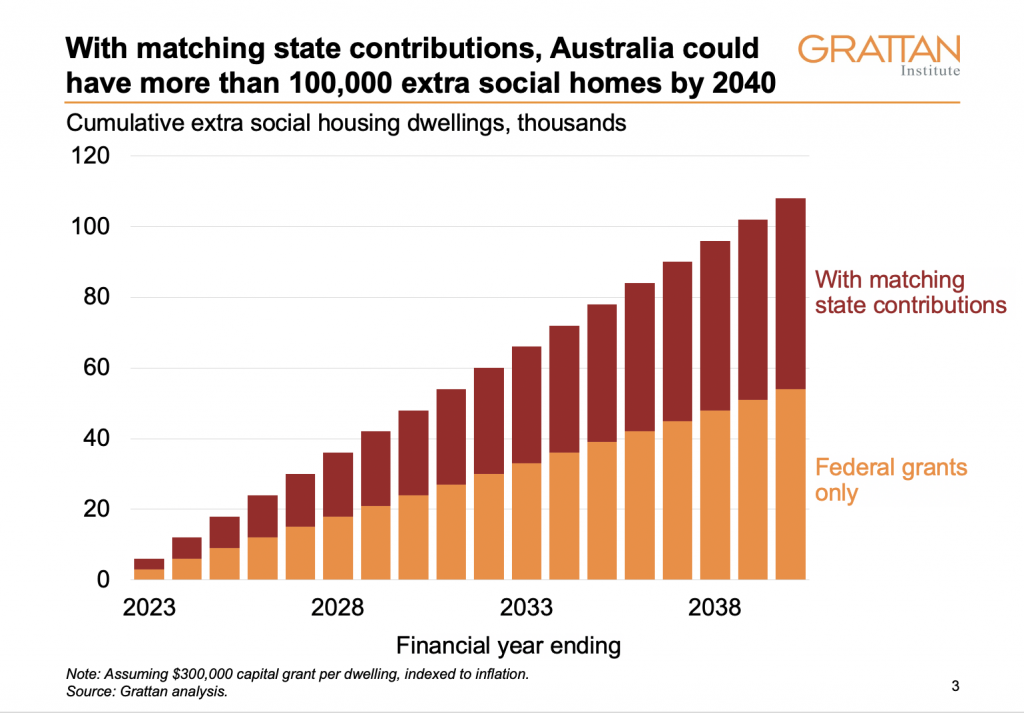

The Federal Government should require state governments to match federal contributions to new social housing, as a condition of any grants being allocated to their state. Any state that does not agree to provide matching contributions would be ineligible for any capital grants for social housing in that year, with the proceeds instead reinvested in the Future Fund and re-distributed across all states the following year.

If matched state funding was forthcoming, the Future Fund could provide 6,000 social homes a year – enough to stabilise the social housing share of the total housing stock.18 It would double the total social housing build to 48,000 new homes by 2030, and 108,000 by 2040.

More social housing alone won’t solve Australia’s housing crisis

Given its costs, social housing should be reserved for people who are most in need and at significant risk of becoming homeless for the long term.19 An unprecedented boost to the social housing stock – such as an extra 100,000 dwellings – would make a big difference to people who are homeless if it were tightly targeted towards them,20 but even then more than two-thirds of low-income Australians would still remain in the private rental market.

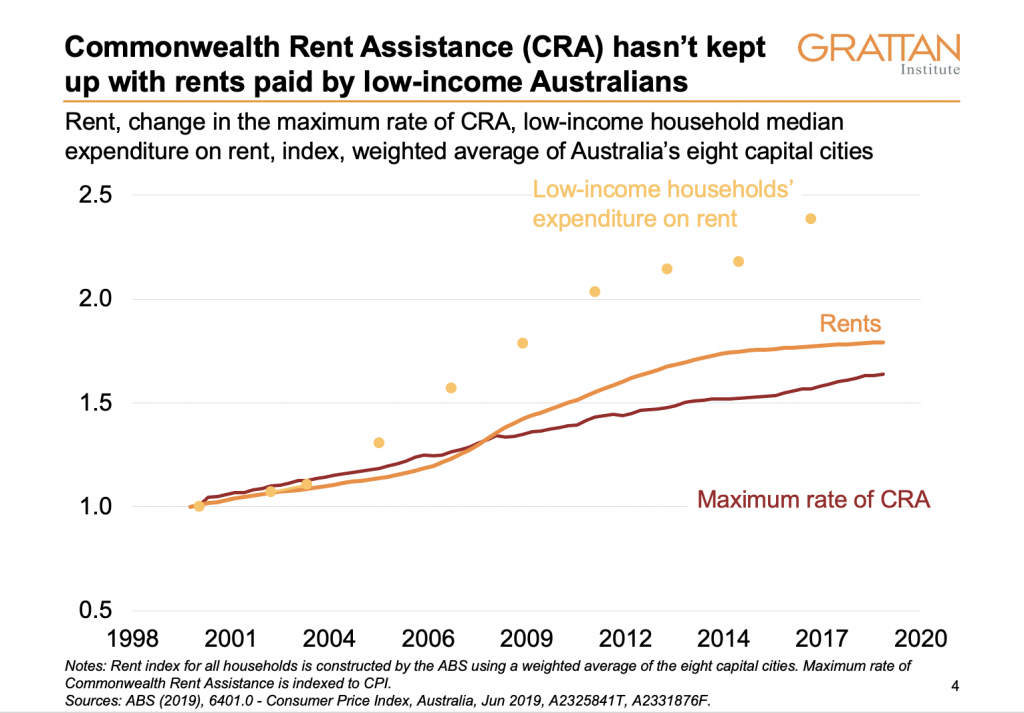

Beyond ensuring a flow of additional social housing for those at greatest risk of long-term homelessness, further support for low-income housing should be focused on direct financial assistance via increases in Commonwealth Rent Assistance.

Commonwealth Rent Assistance should be boosted by at least 40 per cent and it should be indexed to changes in rents typically paid by people receiving income support. This would be a fairer and more cost-effective way to reduce financial stress and poverty among poorer renters. It’s well targeted: about 80 per cent of Rent Assistance goes to the poorest fifth of households. Rents wouldn’t increase much, because only some of the extra income would be spent on housing.21

State governments should also relax planning rules that prevent more homes being built in inner and middle-ring suburbs of our largest cities,22 and the Federal Government should provide incentives to the states to do so. And states should reform tenancy rules, to make renting more secure.

A Social Housing Future Fund alone wouldn’t solve the housing crisis for low-income Australians. But it would give a much needed helping hand to some of our most vulnerable citizens, and ensure social housing will be available for future generations should they need it.

Footnotes

- Infrastructure Victoria found that social housing tends to be effective at reducing homelessness. Only 7 per cent of residents placed in social housing subsequently become homeless, compared to 20 per cent of similar renters in the private market.

- The gross number of social rental lettings dropped from 52,000 in 1991 to 35,000 in 2017 (Pawson, H., Milligan, V., & Yates, J. (2020), p. 106).

- Grattan analysis of ABS Survey of Income and Housing 2017-18. Low-income defined as poorest 40 per cent by equivalised household disposable income.

- Social housing, like any other housing, may also appreciate over time, improving the net worth of state governments and community housing providers. However, any gains can only be realised by selling the social housing stock, meaning it can no longer be made available as social housing to vulnerable renters.

- Markets rents, plus any expected capital gains, normally provide a fair return on investment, covering these costs over the life of the asset.

- It’s the subsidy gap, rather than the upfront financing cost, that reflects the true cost to government of providing social housing. Part of the upfront cost of financing social housing is supported by the (discounted) rental payments made by the tenant. For instance, the Affordable Housing Working Group established by the Council on Federal Financial Relations estimated that the rental payment from tenants could support debt equating to 40 per cent of upfront construction and land costs.

- Estimates of the average upfront cost of building a unit of social housing range from $240,000 to $330,000. For instance, the Social Housing Acceleration and Renovation Program (SHARP) estimates the cost of building 30,000 new social housing units at $7.2 billion, or $240,000 per dwelling. A separate proposal by the CFMEU and Master Builders Australia estimated the cost of building 30,000 social housing units at $10 billion. A recent AHURI (Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute) paper estimated the cost of additional social housing nationally was about $270,000 per dwelling in 2018, or roughly $300,000 by 2022-23. In practice, the required subsidy would be determined via a tender, or reverse auction, ensuring government maximises value for money.

- As of 30 September 2021.

- These approaches are no different in practice to establishing an endowment via borrowing, since asset sales or budget savings could have been used to retire existing public debt instead. Similarly, existing Future Funds could be liquidated to reduce net debt today.

- The Australian 10-year government bond rate was 1.78 per cent as of 22 November 2021.

- The NSW Social and Affordable Housing Fund was financed from the proceeds of privatising the state’s electricity infrastructure.

- By increasing the nominal value of the fund in line with inflation, the fund would be able to maintain the real value of capital grants in line with costs of constructing more social housing.

- Alternatively, fixed subsidies could be set that vary depending on dwelling size and location, based on independent assessments of the costs of providing social housing in different locations.

- For instance, the 2021-22 federal Budget projects $482 billion in Federal Government receipts for the 2021-22 financial year, rising to $572 billion by 2024-25.

- Actual cost of capital grants would be determined by a reverse auction run by the NHFIC. The cost of capital grants would be expected to rise in line with inflation in future years. Alternatively, the dividends could fund annual availability payments for 60,000 new social homes, assuming availability payments of $15,000 a year for 10-15 years. However, using availability payments would commit all Future Fund returns for a 10-15 year period, providing no further additions to the social housing stock in the interim. The federal ALP appears to have adopted this approach, at least in part, for its Housing Australia Future Fund policy, announced in May 2021.

- Assuming an average real government bond yield of 2 per cent on the outstanding debt. Borrowing costs could be higher if the government bond yield rises, which may reduce the returns available to fund social housing for a given fund endowment, above government borrowing costs. However risk-free interest rates are likely to remain lower, for longer, than they have in the past. There is also a strong case for locking in low borrowing costs today to support the Future Fund over the next decade.

- The federal government raises more than 80 per cent of the tax revenue and provides almost 45 per cent of state revenue. See NSW Federal Financial Relations Review Final Report, p. 14.

- There are 436,300 social housing dwellings as of 30 June 2021. Australia’s population has grown at an average rate of 1.4 per cent a year over the past 40 years. The 2021 Intergenerational Report expects Australia’s annual population growth to decline over the next 40 years to 0.8 per cent in 2060-61. Using projected population growth rates from the 2021 Intergenerational Report, Australia needs 104,430 new social housing units by 2040 to sustain the current social housing share of the total stock, on the basis that the latest IGR expects population growth to slow to 1.1 per cent by 2040. Should population growth remain at 1.4 per cent a year going forward, we would need 131,000 extra social housing units by 2040.

- Nearly three-quarters of social housing allocations in 2019-20 went to ‘greatest needs’ applicants.

- There were 116,000 homeless Australians on Census night in 2016. Coates and Chivers, Who is homeless in Australia?, Grattan Blog.

- A recent AHURI paper estimates that between 7 and 33 cents of any increase in Commonwealth Rent Assistance would be passed forward into higher rents.

- Lowering market rents by, for example, 20 per cent would boost the post-housing incomes of low-income private renters by more than $3 billion a year, equivalent to an increase of more than 80 per cent in the maximum rate of Commonwealth Rent Assistance.

Brendan Coates

While you’re here…

Grattan Institute is an independent not-for-profit think tank. We don’t take money from political parties or vested interests. Yet we believe in free access to information. All our research is available online, so that more people can benefit from our work.

Which is why we rely on donations from readers like you, so that we can continue our nation-changing research without fear or favour. Your support enables Grattan to improve the lives of all Australians.

Donate now.

Danielle Wood – CEO