The Albanese Government decision to revise the Stage 3 tax cuts has ignited a political firestorm.

The Government argues that revising the tax plan to offer bigger tax cuts to low- and middle-income earners struggling with the cost of living justifies breaking an election promise.

But the Opposition says the changes will make bracket creep worse in the long term, because they will increase tax revenue by $28 billion over 10 years, compared to the original Stage 3 tax cuts.

So who wins from the revised tax plan, now and into the future?

Low- and middle-income earners win, high-income earners lose

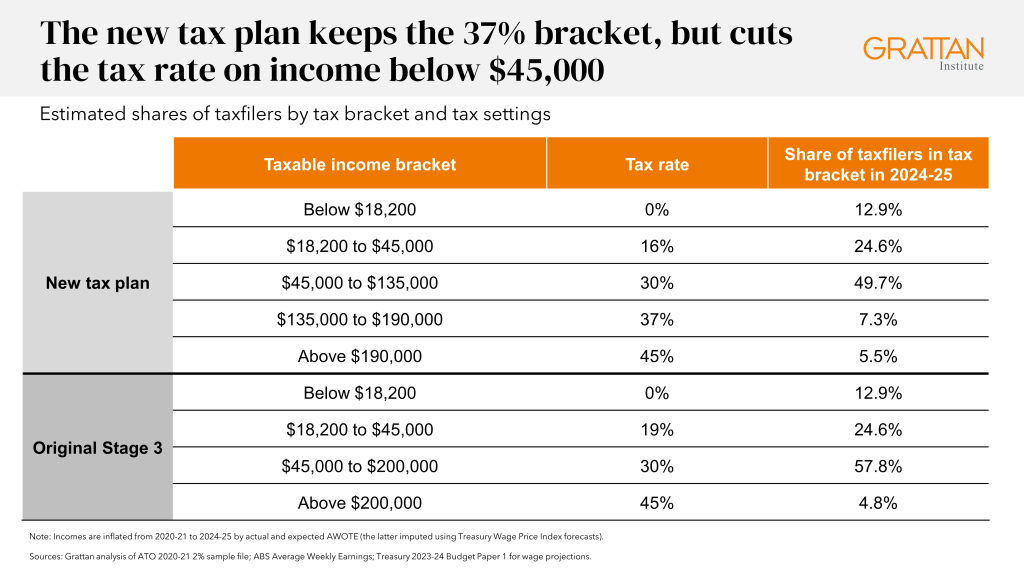

The Government plans to cut the bottom tax rate, which applies to incomes below $45,000, from 19 per cent to 16 per cent. That will give a tax cut of up to $804 a year to all taxfilers, including those on higher incomes.

At the same time, the Government plans to reduce the Stage 3 tax cuts for higher earners.

Under the Stage 3 tax cuts, a single 30 per cent rate was to apply to incomes between $45,000 and $200,000. Instead, the Government wants this rate to apply to incomes between $45,000 and $135,000.

The existing 37 per cent rate, which Stage 3 was to abolish, will instead be retained, and apply for incomes between $135,000 and $190,000.

And the top rate of 45 per cent will remain for incomes above $190,000, rather than the $200,000 level envisaged under Stage 3.

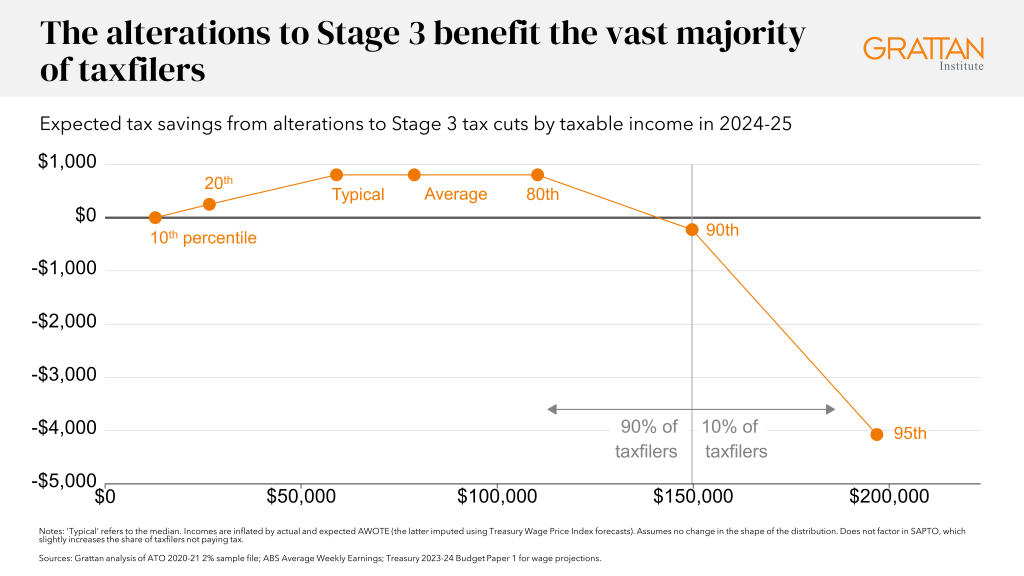

The upshot is that people with taxable incomes of less than about $146,486, or nearly 90 per cent of all taxfilers, will get either the same or a larger tax cut under the new plan.

Whereas the 10 per cent with higher incomes will get smaller tax cuts than under the original Stage 3. The tax cut for people who earn more than $200,000 a year – expected to be less than 5 per cent of taxfilers in 2024-25 – will be roughly halved, from $9,075 to $4,529 a year.

Bracket creep will erode the value of these tax cuts over time

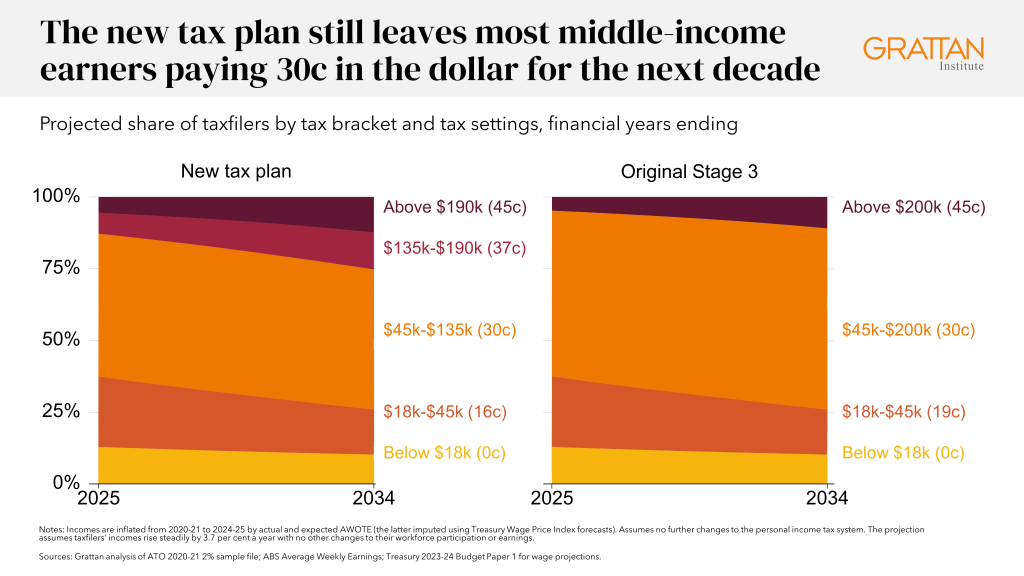

Australia’s tax scales are not indexed to wages growth or inflation. That means that as our incomes rise, including just to compensate for inflation, Australians pay a higher proportion of their income in tax.

Even if wage growth doesn’t push a taxpayer into a higher tax bracket, most taxpayers will still earn a bigger share of their income in their highest bracket, so end up paying more tax.

Over time, this so-called ‘bracket creep’ increases average tax rates across the income distribution as wages grow. It’s why governments regularly return the proceeds of bracket creep in the form of tax cuts.

And one consequence of keeping the 37 per cent tax bracket for incomes between $135,000 and $190,000 is that average tax rates will rise more quickly for some upper-income earners than they would have under the original Stage 3.

The share of people with a taxable income between $135,000 and $190,000 is expected to rise from 7 per cent in 2024-25 to 13 per cent in 2033-34 due to bracket creep.

And the share of taxfilers in the top tax bracket – above $190,0000 – is expected to rise from 6 per cent next year to 12 per cent in a decade’s time.

But Middle Australia still wins in the long term too

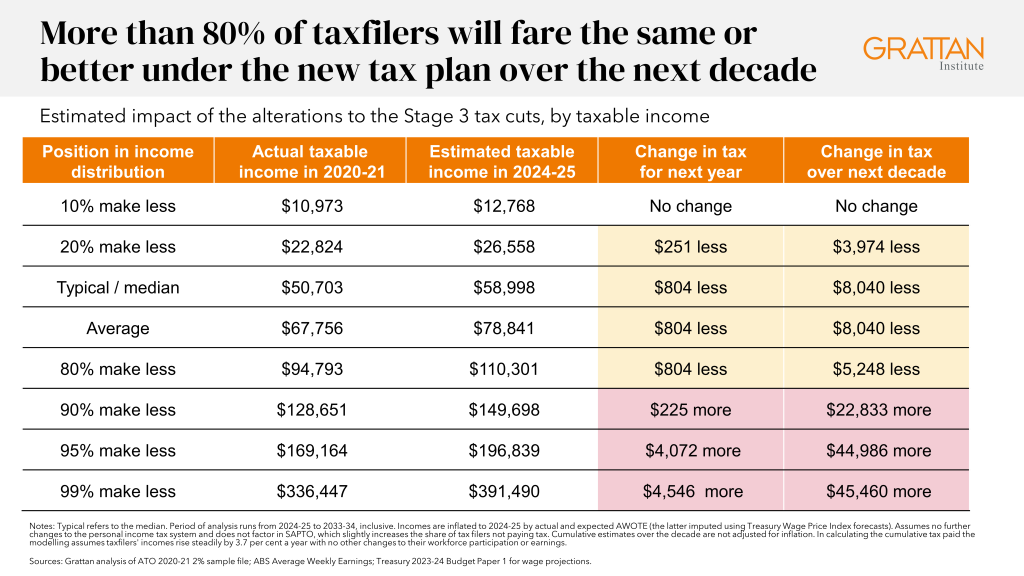

Our analysis shows that the vast bulk of Australian taxfilers benefit from the revised tax package, despite the impact of bracket creep over the next decade.

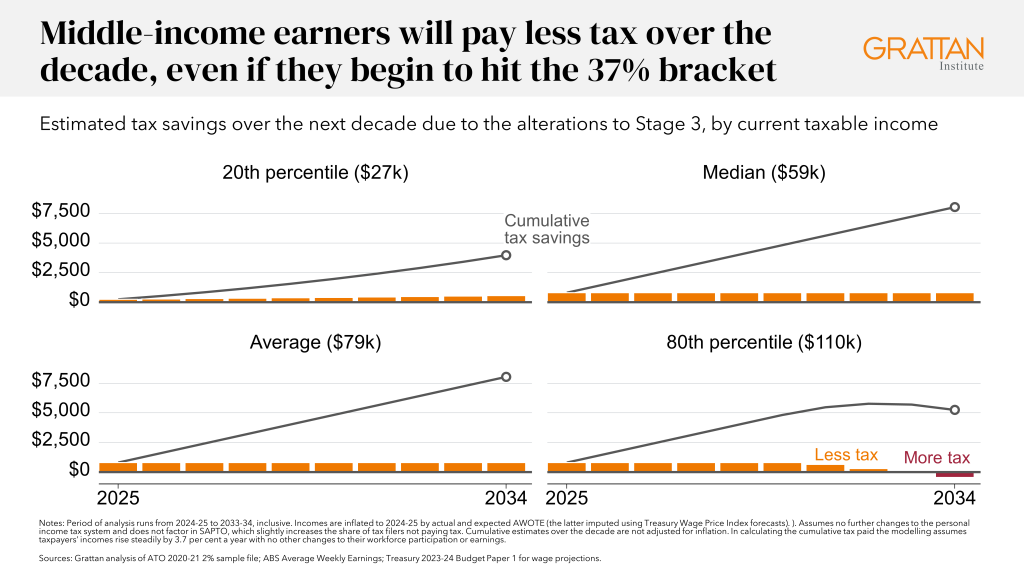

For example, the typical taxfiler, who can expect a taxable income of about $59,000 in 2024-25, will pay $804 less in tax next year. As will someone on the average taxable income of about $79,000 in 2024-25, who earns more than nearly two thirds of Australians.

And both can expect to still be receiving the full extra $804 a year in tax cuts in 2033-34. And they will have paid cumulatively $8,040 less in tax over the next decade, compared to if the original Stage 3 tax cuts remained in place.

Even higher-income earners who jump into the 37 per cent tax bracket that applies to incomes above $135,000 in the next few years will still be better off over the decade.

Under the Government’s new tax plan, someone with a taxable income of about $110,000 in 2024-25 (more than 80 per cent of taxfilers) can expect to tip over into the 37 per cent tax rate by the start of the next decade. But because they will pay $804 a year less in tax for several years before then, they will still pay about $5,200 less in tax over the decade under the Government’s plan, compared to under the original Stage 3 plan.

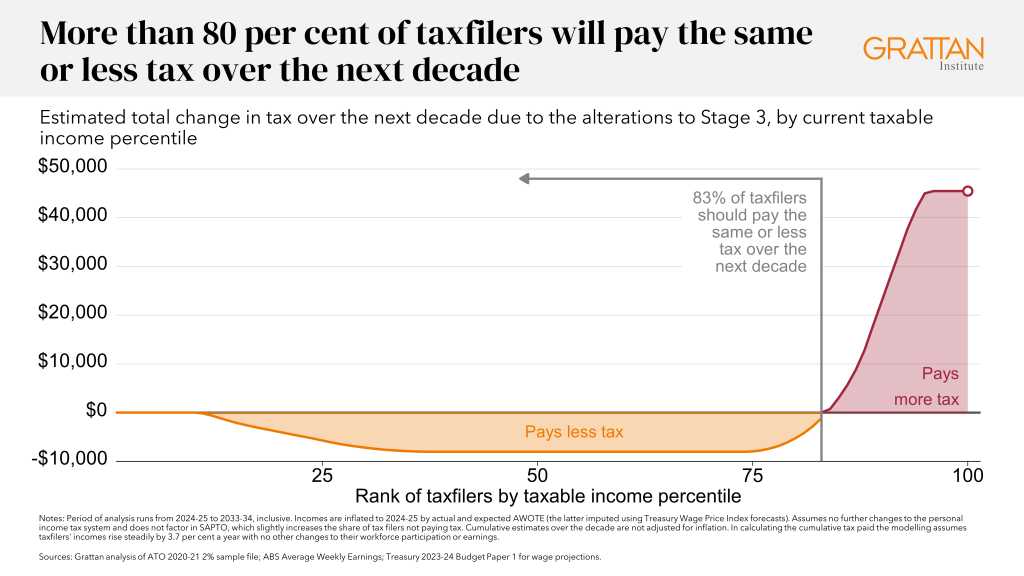

So while the share of taxfilers facing a higher average tax rate each year under the new tax plan will grow over time – from about the top 10 per cent today to around 22 per cent by 2033-34 – the accumulated savings over time means many are likely to still be better off over the next decade.

After all, if the purpose of the tax cuts is to return bracket creep, the true test is whether taxfilers pay less or more tax over the next decade.

And we estimate that roughly 83 per cent of taxfilers should expect to pay the same or less tax over the next decade under the Government plan than they would have under the original Stage 3. 1

There will be at least three federal elections between now and 2033-34. So the chances are high that there will be further changes before then to tax rates and thresholds, to return future bracket creep.

But high-income earners will pay substantially more tax over the next decade under the Government’s tax plan than they would have under Stage 3.

Someone with a taxable income higher than 95 per cent of all Australians – that is, about $197,000 in 2024-25 – will probably pay about $45,000 more in tax than if the original Stage 3 had remained in place.

Those struggling the most miss out

The Government argues that its tax plan offers cost-of-living relief to low- and middle-income earners struggling with inflation. But what’s missing from the Government’s package is relief for those genuinely struggling the most, and who don’t benefit from these tax cuts.

Nearly one-third of Australian households don’t pay tax at all – retirees, people with a disability, carers, and the unemployed. Many of these Australians are among those doing it toughest.

Unemployment benefits have fallen dramatically below the poverty line. JobSeeker only increases with inflation, whereas the Age Pension is indexed to both inflation and wages. This has ‘squeezed’ the living standards of people living on unemployment benefits. Even the combined $45 per week increases in these payments since 2021, by both Coalition and Labor governments, has done little to bridge the gap.

And low-income renters have been especially hard hit. Rents are rising at an annual rate of more than 7 per cent, and one third of low-income renters have less than $500 of savings on hand in the event of an emergency.

The Government should urgently extend cost-of-living support to Australia’s most vulnerable.

It should turn last year’s 15 per cent increase in Rent Assistance into a 40 per cent increase. This would provide an extra $1,000-a-year to low-income renters, at a cost to the budget of about $1.2 billion a year.

The Government should also raise Jobseeker and other working-age allowance payments by at least a further $55 a week, which would cost about $3.5 billion a year.

The budget is the biggest loser

The biggest loser from the revised tax plan may end up being the federal budget.

The Government’s tax plan, like the original Stage 3 tax cuts, will cost more than $20 billion a year, or nearly 1 per cent of GDP.

And that budgetary cost would be larger still if a future Coalition government kept the Stage 3 benefits for high-income earners and kept the bigger tax cuts for low- and middle-income earners under the Labor plan.

That would increase the cost from more than $20 billion a year to upwards of $30 billion a year, and by up to an extra $115 billion over the decade in the long term.2

While the budget is riding high in the short term on high commodity prices, Australia still faces a structural budget deficit of up to 2 per cent of GDP, or almost $50 billion a year in today’s dollars.

These tax cuts will make it harder for this government, and future governments, to meet community demands for more spending in areas such as healthcare, aged care, disability care, and defence.

These tax cuts will also make it harder for governments to make other growth-boosting tax reforms, such as raising the GST to fund cuts to other, less efficient taxes, as now advocated by many commentators.

Such reforms typically cost the budget revenue as extra money is paid out to compensate the losers. The commitment of both major parties to big income tax cuts now, means there will be less money in future to ‘buy’ more worthwhile reforms.

Footnotes

- Modelling assumes all taxfilers’ incomes rise by 3.7 per cent a year, in order to assess the impact of bracket creep over time at different points in the income distribution.

- Grattan analysis of the Parliamentary Budget Office SMART model.