Thanks so much for having me here today on beautiful Nipaluna country, I would like to pay my respect to elders past and present.

I am honoured to be giving this lecture on behalf of the excellent economist and proud Tasmanian Lyndhurst Giblin.

I first became aware of Giblin when I got curious after studying in the building that bears his name at Melbourne Uni.

At that time I was most fascinated by the diversity of his career, and indeed I still think anyone whose biography includes economics professor, head statistician of Tasmania, unsuccessful gold prospector, timber cutter in Canada, member of the Commonwealth Grants Commission, rugby union player for England, fruit grower in Tasmania, soldier in the First World War and Director of the Commonwealth Bank is pretty impressive![1]

But what now impresses me most is Giblin’s economic communication. He recognised and prioritised the importance of explaining economics to the public.

As his colleague and fellow Economic Professor Torleiv Hytten wrote of him:[2]

Economics has always been called a dismal science, and one must admit that many of its proponents tend to be dull writers, but that could never be said of Giblin. Perhaps none of his writing could be classed as of high theoretical value, but high sheer common sense and good humour made him a valuable proponent of economic theory for the uninitiated. One never gets tired of reading, because his argument is always clear, and is brightened with some breezy remark.

His series of press articles during the Great Depression, titled “Letters to John Smith, the causes of the crisis”, was an attempt to explain to a bewildered and hurting public what was going on, as well as to make the difficult case that wages would need to fall to remedy the situation.

His book on Australian tariffs, co-authored with several other leading economists, is a masterclass in nuanced discussion on both direct economic effects, but also distributional impacts and effects on psychology and national identity.[3]

It stands as a useful reminder of how stripped back economics became in later decades, often deliberately abstracting from this important contextual understanding of the social impacts of policy and policy change.

It was a highlight for me to read some of Giblin’s work in preparing for this lecture. Such clear and robust thinking combined with great writing is indeed rare in economics, and I want to recognise that aspect of Giblin’s incredible work history tonight.

And so to our topic tonight.

Picking apart the nuances of economic outcomes between generations requires a Giblin-esque focus on context and psychology.

On many measures, living standards continue to improve over time, so some will argue that young people have it better than ever.

But survey after survey shows young people struggling with the economic hand that they have been dealt. A 2022 Pew research survey showed that 72 per cent of Australians thought that Australian children growing up today would be financially worse off than their parents. This was a 14 percentage point increase on the previous year.[4]

In a recent survey of Gen Zs, one in three reported struggling with their mental health. Two in three reported problems sleeping. When asked about the issues keeping them up at night, 78 per cent chose the cost of living, 67 per cent chose housing and rental affordability, and 60 per cent nominated climate change.[5]

In other words, economic and environmental issues loom large for today’s youth.

And that is understandable. Because today’s policy landscape, sometimes by accident and sometimes by design, has prioritised the needs of older generations over young people now and in the future.

So this evening I want to explore the issues that young people tell us are keeping them up at night and, in the spirit (although sadly not the execution) of Giblin, let them know why this has happened but also what we might as a nation do about it.

Part 1 – Navigating a cost-of-living crisis with less economic fat

It’s no secret that in the past year and half, the affordability of a whole range of goods and services has declined.

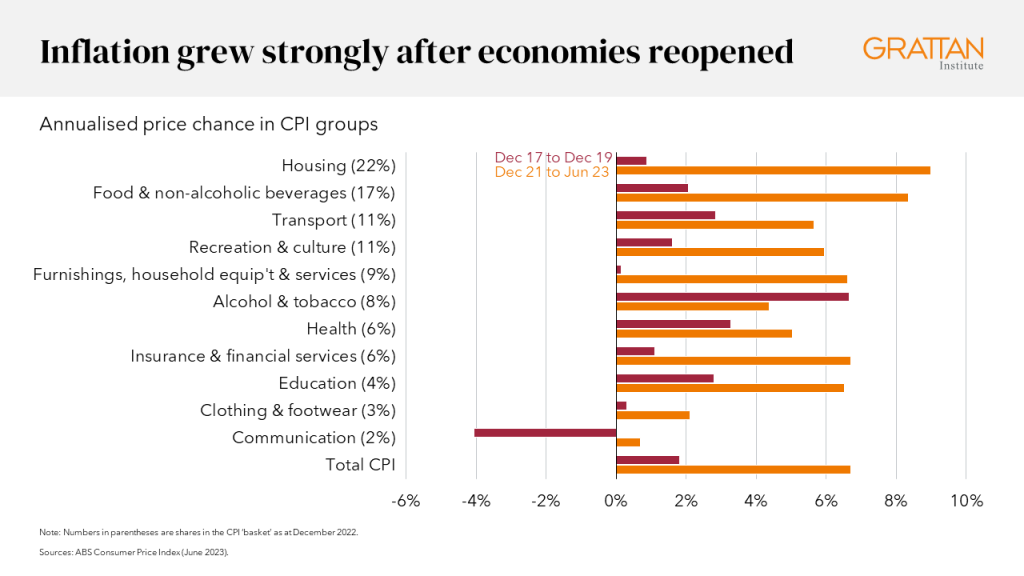

Since December 2021, CPI has grown on an annualised basis by 6.7 per cent, including increases of 9 per cent for housing, 8.3 per cent for food, and 5.6 per cent for transport – the three biggest items in the CPI basket. Over the same period, base wages have grown by only 3.2 per cent, meaning that the average Australian wage-earner has had a contraction in their real living standards.[6]

Putting housing costs to one side for now, these increases in the costs of goods and services across the economy hit all age groups. And indeed, Grattan Institute analysis does not find evidence that young people have seen the cost of their CPI consumption basket grow faster than that of older Australians.[7]

BUT there are reasons why inflation is biting young people particularly hard.

Younger people have less ‘economic fat’ to buffer them against the current rise in real living costs.

First, young people have less discretionary spending in their consumption bundle. This means they have less scope to reduce their spending before having to cut back on essentials. Households headed by someone under 45 spend substantially more as a share of income on housing and education than older households. Of the non-discretionary items, only health spending is substantially higher for older households.

And this reflects a longer-term trend: in the pre-COVID world, the growing cost of essentials – particularly housing – meant that younger people had increasing oriented their consumption bundle towards these essentials.

Indeed, in the period from 1989 to 2016, non-essential spending shrank for young people in real terms. Indeed, all households headed by someone under 55 shrank their spending on non-essential goods overall – partly helped by decline in the cost of some of these ‘nice to haves’, such as clothing and household furnishings.

But for older households, the reduction in spending in these categories was much smaller and was dwarfed by an increase in spending in recreation, which includes travel.

So despite the regular handwringing about Millennials choosing smashed avocado brunches over financial responsibility, even before the recent pressures younger people had increased their spending less than older generations. And all the growth in younger people’s spending was because of spending on essentials.

Second, younger people tend to have less in the way of wealth buffers.

For people seeking to maintain consumption in periods where prices are growing faster than incomes, the only ways are to reduce savings – an effect that has been very apparent with the decline in the household savings ratio – or to drawdown on existing wealth (negative savings).

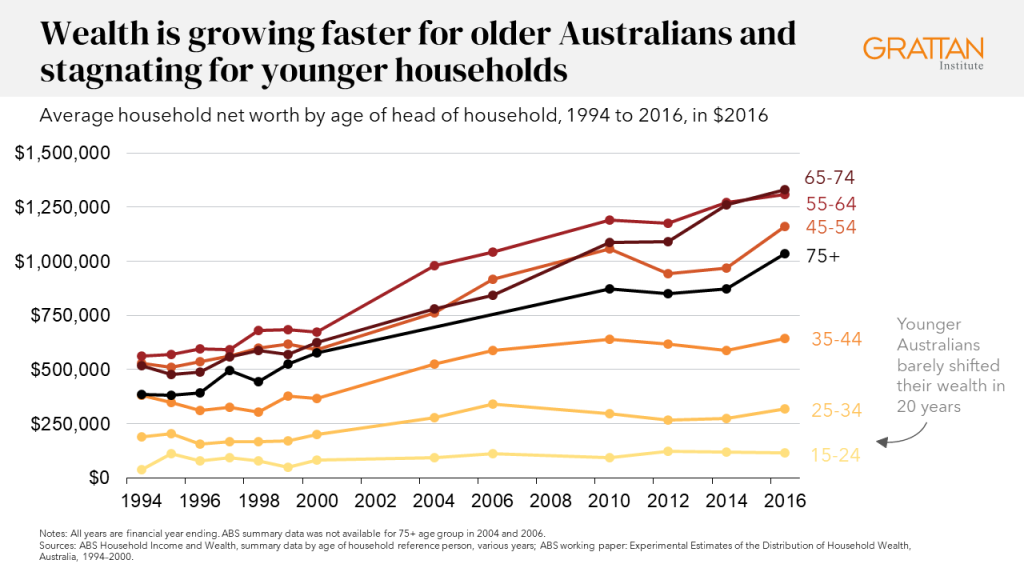

For those without any savings to cut back, younger people have less in the way of wealth buffers to rely on. The average household headed by someone aged 25-34 had $317,000 net wealth in 2016, the vast bulk of which is in their home or in superannuation, which they are many years away from being able to access. For households 65-74 that figure was $1.3 million, including a much higher share of liquid assets.

The effect is that young people overall just have far less peace of mind around their capacity to cope with economic shocks, including an extended period of very high price growth.

A 2019 survey found that amongst 18-24 year-olds, almost half would only be able to cover living expenses for up to one month if they lost their job tomorrow.[8]

This is consistent with ABS data, which show that in 2019-20, half of all 18-24 year-olds had less than $2,000 in the bank in case of an emergency.

The third and final way in which younger people are particularly being squeezed is in the economic policy response to high inflation. Monetary policy remains our frontline tool for dealing with prices growing more quickly than we would like.

The Reserve Bank, just like other central banks around the world, has responded aggressively to stamp out the current bout of inflation. It has increased interest rates 12 times, for a total rise of 4 percentage points since March 2022.

This strong and decisive response from the RBA is ultimately the best thing for the country. A country that fails to take inflation seriously will eventually just end up with a bigger mess to mop up later.

But as the outgoing Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe is always keen to remind us, the cash rate is a blunt tool to slow inflation and one that has very different impacts on different groups. As he noted in his recent appearance before the Standing Committee on Economics:[9]

“Some people in the community are finding things really difficult from higher interest rates, and other people are benefiting from it.”

Nowhere is this differential impact more pronounced than across age groups.

One key channel by which interest rates work their economy-slowing magic is through squeezing household cashflows.

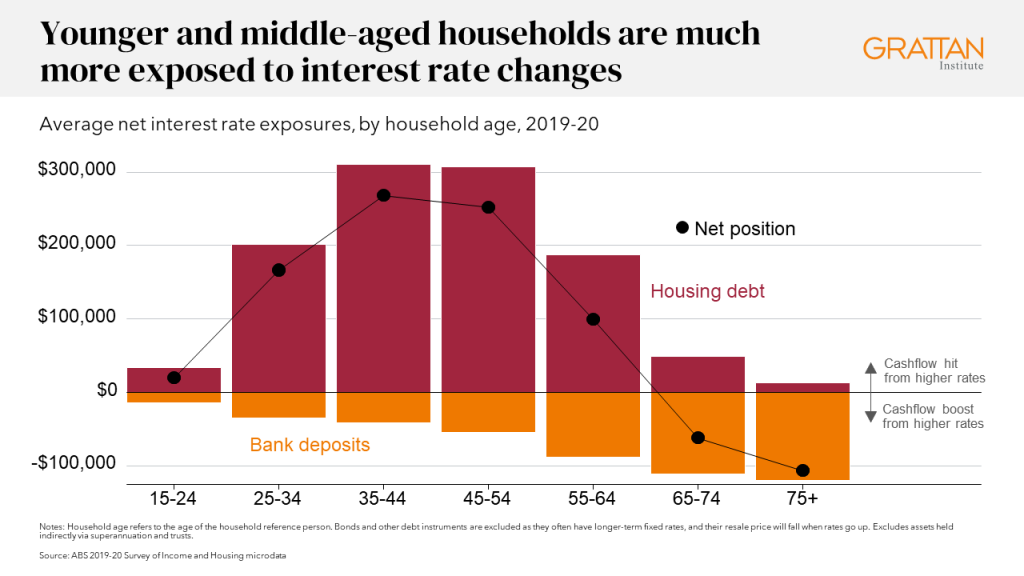

Higher interest rates reduce the spare cash flow of households with debt, particularly mortgages.[10] This effect is to reduce spending for the more than 3 million, or 1/3 of Australian households, in this group, compared to the counterfactual.

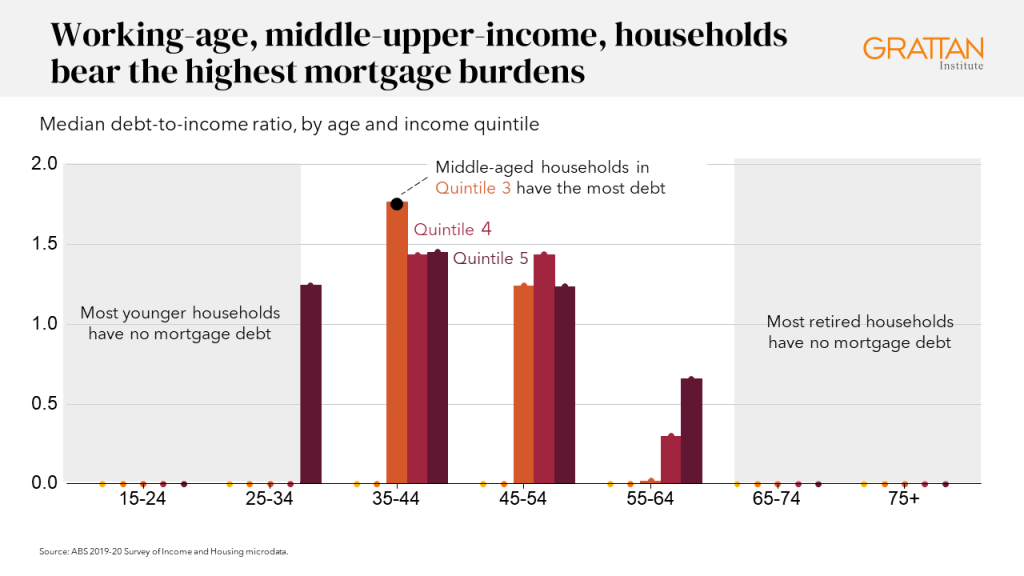

But mortgage debt is concentrated among 25-65 year-old households, and is particularly large in net terms among the 35-55 year-olds.

To be more specific, it is the middle- and high-income Millennials and Generation Xers, as well as the higher-income Generation Z’s, who are on the frontline of the Reserve Bank’s attempt to crunch consumer spending.

But the flip side of the household cashflow channel is higher income among those who hold interest-earning assets. While high inflation has eroded the value of their savings, the response to high inflation – higher interest rates – has put more money in their pockets.

And the beneficiaries of this channel have been overwhelming older Australians. Indeed, those over 65 benefit in net terms from the cashflow effects of higher interest rates.

Richer older households are estimated to have had a cashflow boost of more than $1,000 since interest rates started going up.

And this puts aside the cash savings many older households can access in their super. Up to 16 per cent of all accessible variable-interest assets sit in the super accounts of older, mainly wealthier, Australians who are free to withdraw and spend the extra interest.[11]

Of course, the cashflow channel is not the only way in which interest rates affect the position of households.

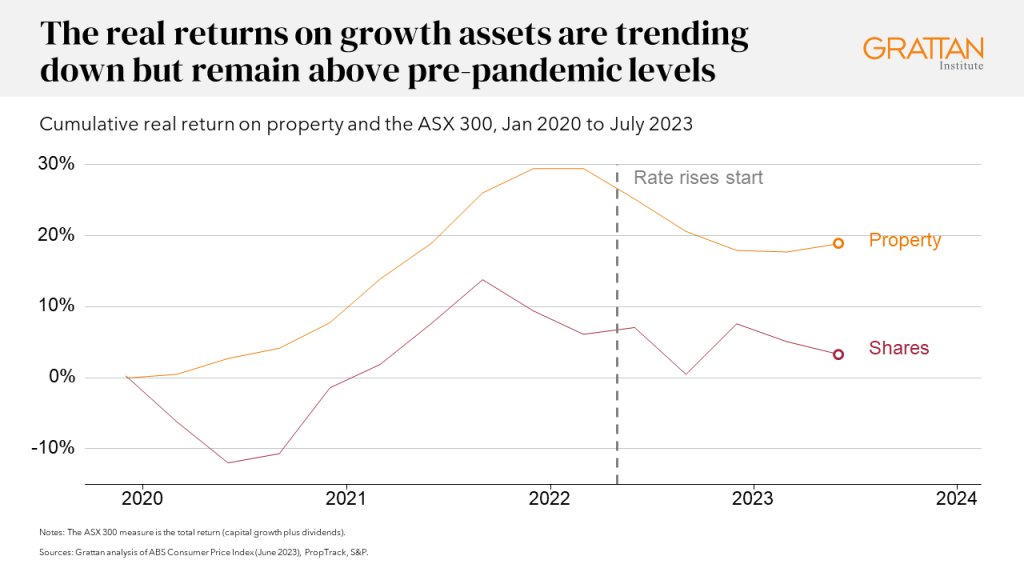

Higher interest rates may also reduce spending through so-called ‘wealth effects’, by reducing the value of prices of houses and shares, although the evidence on the strength of this effect is mixed.[12]

This could have a more pronounced effect on older Australians, given they hold a lot more assets. So far in this tightening cycle, any wealth effects on spending seem to be muted, as we will see.

This may reflect the fact that older households are still spending down large excess savings accumulated during the pandemic. It could also be because, despite now trending down in the face of high inflation, the real value of property and shares is still above pre-pandemic levels.

So pulling this altogether, how have different age groups fared in the current cost-of-living crisis? One important measure is how household consumption has changed.

Using data published by the Commonwealth Bank based on credit and debit card transactions from 7 million customers, we can see that spending changes over the past year are correlated with age.[13]

While the over-55s are ‘living large’, as the kids say – with per capita spending significantly outpacing inflation – younger people’s real consumption has shrunk over the same period. The real declines have been especially pronounced for those aged between 25 and 40.

The enthusiastic spending of older Australians is probably partly ‘revenge spending’ – catching up on the opportunities lost during COVID through drawing down on the excess savings accumulated during that period. But it is also likely to reflect the tailwinds of higher household cashflow because of higher interest rates.

So where does this leave us? Australia’s young people are navigating a cost-of-living crisis with less economic fat, and with the major policy tools to respond to inflation stacked against them.

But the degree of difficulty of this short-term challenge is heightened by longer term structural changes. For today’s young people, the slow-burn issues of an education system under pressure, unaffordable housing, a climate crisis, and growing government indebtedness loom large.

Part 2 – Letting down our kids in school

Education is critical to flourishing in a modern economy. Jobs and Skills Australia estimates that nine out of 10 new roles over the next five years will require some form of post-school education.[14] This reflects the longer-term trend towards services jobs in the economy, many requiring a university degree or vocational education and training qualification.[15]

But for young people to flourish is this new economy, we need to get the foundations right.

Despite growing funding, Australia’s school system has not been delivering the results we want for our young people.

Data from the OECD show that the performance of Australian school students in Reading and Maths – both compared to other countries AND to our own performance over time – is going backwards.

The average Australian 15-year-old student is now more than one year behind in maths compared to where the student of the same age was at the turn of this century. For reading it is about nine months.

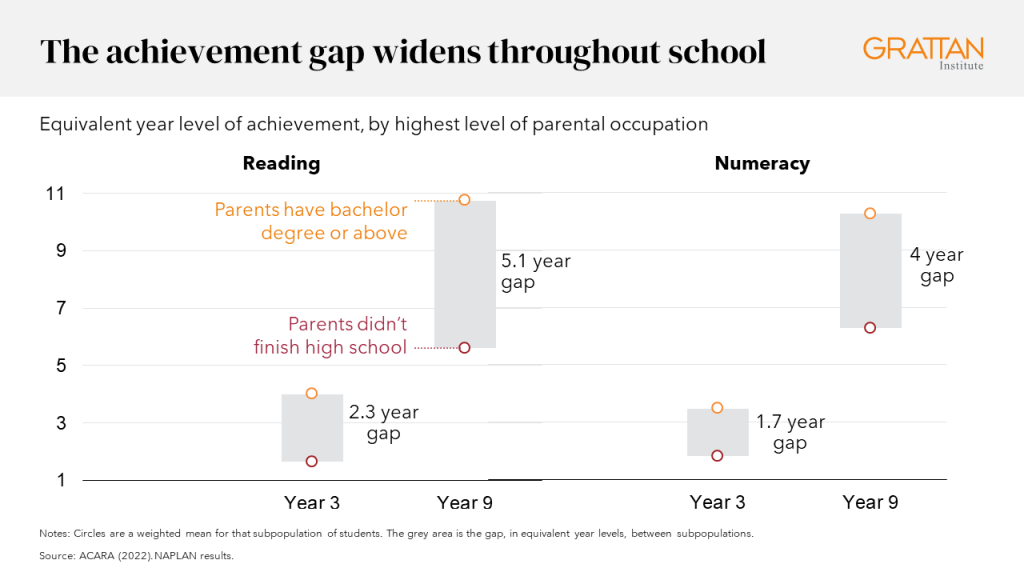

Perhaps even more worrying, the learning gap between students from advantaged and disadvantaged backgrounds more than doubles between Year 3 and Year 9.

This is the same in Tasmania, which has a reading gap equivalent to more than five years of leaning by Year 9 between those whose parents have a Bachelor degree or above and those whose parents did not finish high school.[16]

The 2023 NAPLAN results also paint a concerning picture of student achievement in Tasmania. Tasmania is below the national average in Reading and Numeracy in most year levels. About 40 per cent of Tasmanian students are below expectations for their year level, compared to about 33 per cent nationally. That’s roughly 10,000 Tasmanian students who sat a NAPLAN test and were identified as not on-track with their learning. The small number of high-performing students is also worrying. In every year level, fewer than 10 per cent of Tasmanian students are top performers in numeracy.

I’ll talk more about what we can do to turn this around later. But for now I will just make an obvious point: this should be a first-order policy priority. Not acting handicaps our future growth. Indeed, as Bill Gates has argued, the best leading indicator of a country’s outlook in 20 years’ time is the performance of its education system.[17] But it also handicaps young people themselves. If we do not equip young people with the foundational skills, we magnify the other challenges coming down the pipeline.

Part 3 – Forever renters?

Since World War 2, Australia has been a nation of homeowners. Home ownership rates peaked at more than 71 per cent in 1966.[18] Almost three-quarters of the nation was on the property ladder and living the dream – home ownership was celebrated as an indicator of success, security, and quality of life.

Ownership rates declined very gradually in following decades but then sharply since the early 1990s, when house prices and incomes started to diverge. At the 2016 Census, home ownership rates were at their lowest level since 1954.[19]

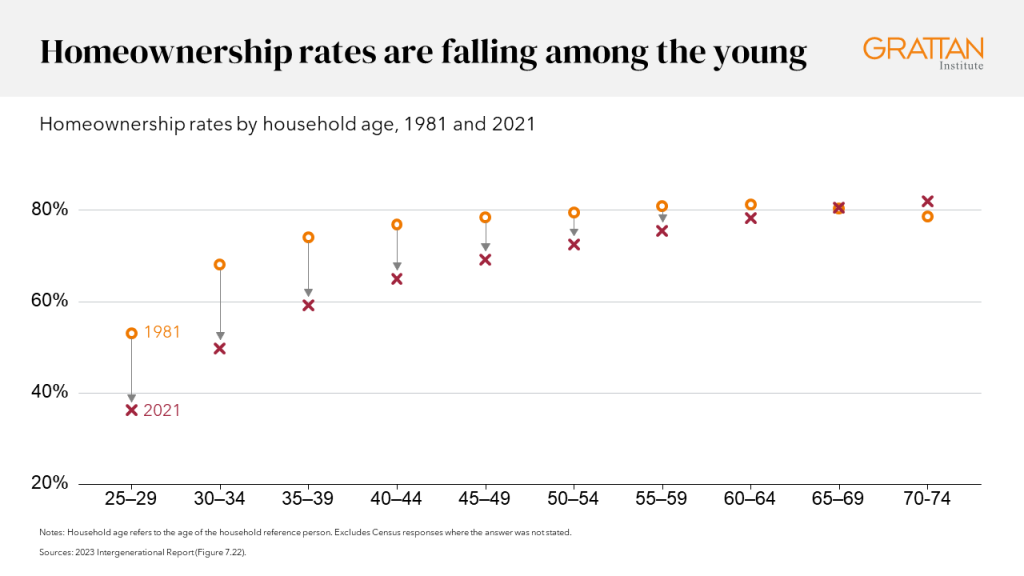

But what has been particularly striking is the drop among young people.

In 1981, when the Boomer generation was settling down and having families, 68 per cent of 30-34 year-olds owned their own home. In 2021, the equivalent figure was 49 per cent. The falls have been particularly pronounced for poorer, younger people, challenging the suggestion that plummeting ownership rates reflect different preferences of today’s young people.[20]

Young people want to own their home as much as ever, but the fact remains that it is now only the richest young people, or the ones with the richest parents, who can afford to.

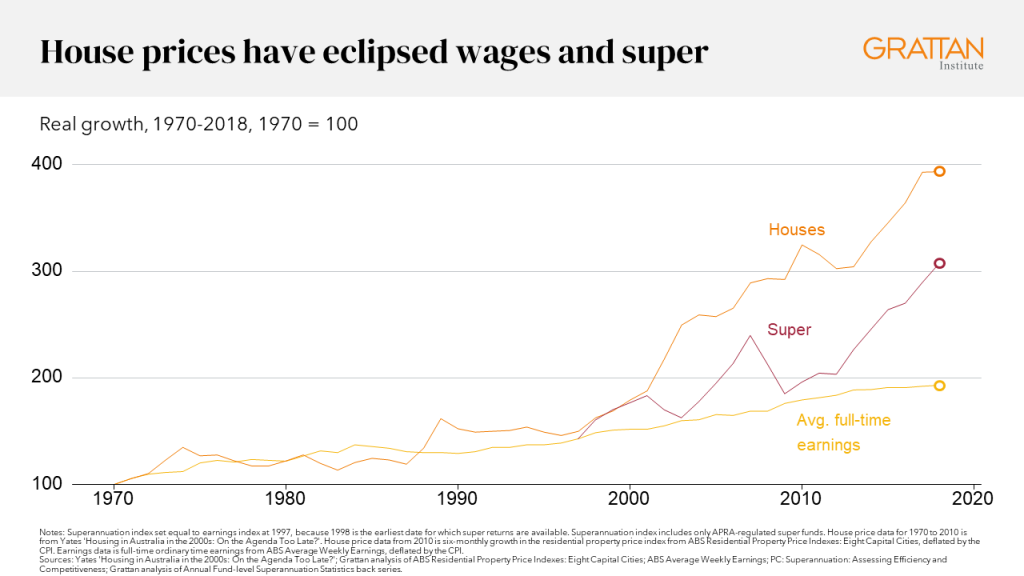

Why is this? Mainly because house prices have exploded over the past 25 years.

Until the late 1990s, house prices broadly tracked growth in incomes. But between 1992 and 2018 they grew at almost three times the pace on average.

The implications for aspiring homeowners are very real.

First, the time taken to save for a deposit has increased dramatically. In the early 1990s it would take the average Australian about seven years to save a 20 per cent deposit for a typical dwelling. Now it takes almost 12 years.

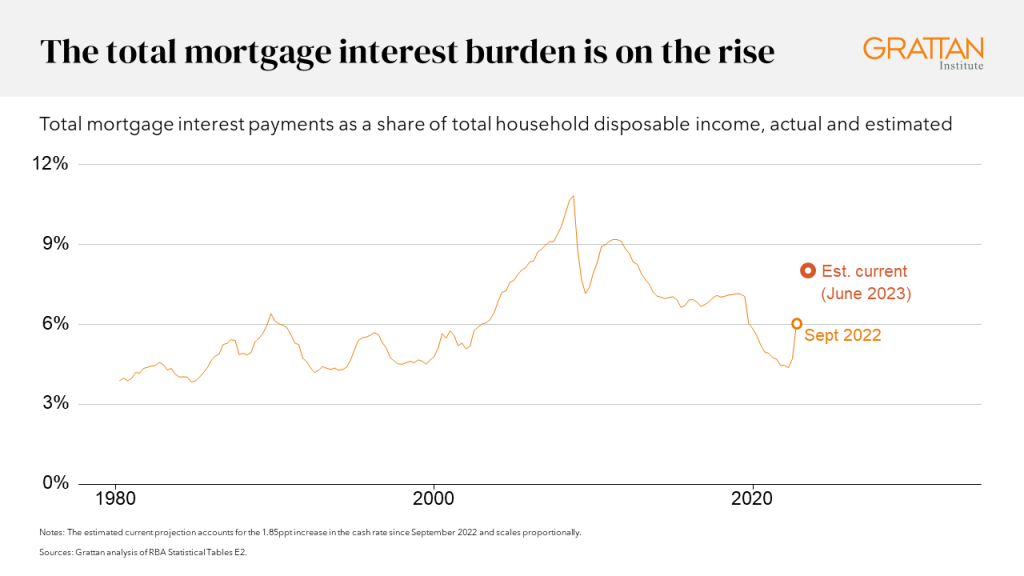

Second, while low interest rates pre-COVID helped with the costs of servicing the substantially larger loans needed to buy, they have increased the ‘repayment shock’ from a given increase in interest rates.

So next time your Boomer uncle regales you with horror stories about 17 per cent interest rates of the early-90s, it’s worth reminding him that 6 per cent rates today are as painful as the 17 per cent rates then for the typical borrower.

Indeed, the costs of servicing mortgages today as a share of total household disposable income are above where they were through the 1980s and 1990s.

There have been two big implications for young people from this shift.

First, there is a much higher share of young people in the rental market, many of whom will be ‘forever renters’.

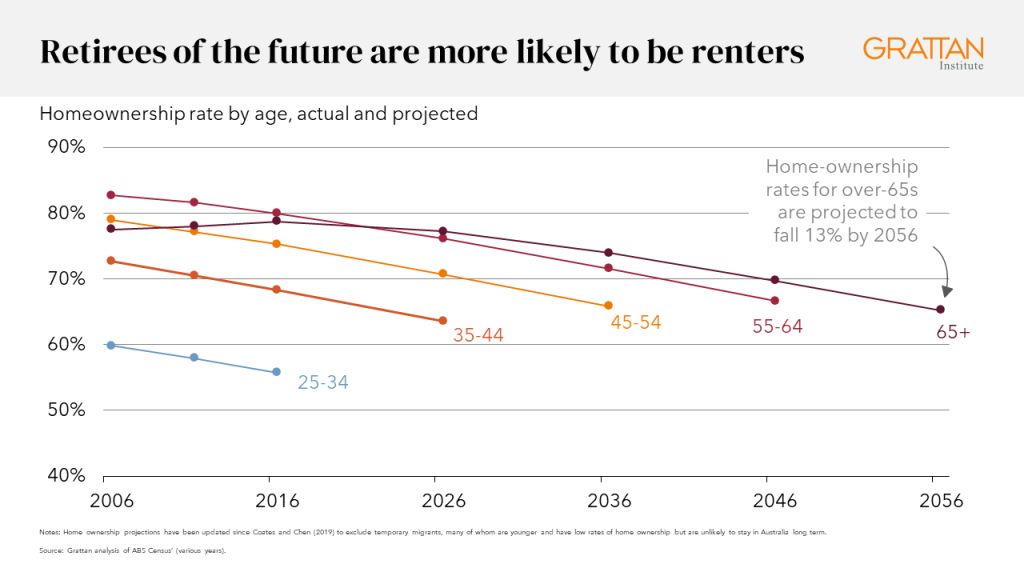

This means many more young families and, in time, more retirees living in rental properties. Indeed, Grattan Institute projections suggest that home ownership rates for over-65s will fall from close to 80 per cent today to 65 per cent by 2056.

That puts a premium on stability of tenure.

Being forced to move, or worrying about the possibility of having to move, is a particular problem for families with children in school, for older people who don’t want to move away from their communities, and for poorer people who struggle to afford the costs of moving.

Yet renters have little assurance that they can stay in a place as long as they want. Most tenancy agreements are for a fixed term of one year (or less). They often then convert to periodic leases (often referred to as month-by-month leases).

Renters move much more often than owners: two-thirds of private renters moved in the past two years, compared to one quarter of owners with a mortgage.[21]

Many more of today’s under-35s face a lifetime of this churn under current policy settings.

Second, we have created a huge disparity in wealth accumulation across generations.

The rapid run up in house prices has created windfall gains for existing homeowners. This has been a major contributor to the rapid growth in wealth among older households.

A household headed by someone aged 65-74 had on average $1.3 million in assets in 2017, up from $900,000 for the same age group in 2004. Rising asset prices over the past seven years mean this figure is almost certainly substantially higher now.

In contrast, the wealth of households under 35 has barely moved in 15 years. And poorer young Australians have less today than poorer young Australians did 15 years ago.

Part 4 – The Jane Austen world

The inevitable riposte to these concerns about widening gaps in generational wealth accumulation is, ‘inheritances will fix the problem’.

It is true inheritances will be a huge feature of the Australian economy in future decades.

With a swelling of our national household wealth to $14.8 trillion – up more than 190 per cent in real terms since the GFC[22] – most in the hands of older Australians, there is an awfully big pot of wealth to be passed on.

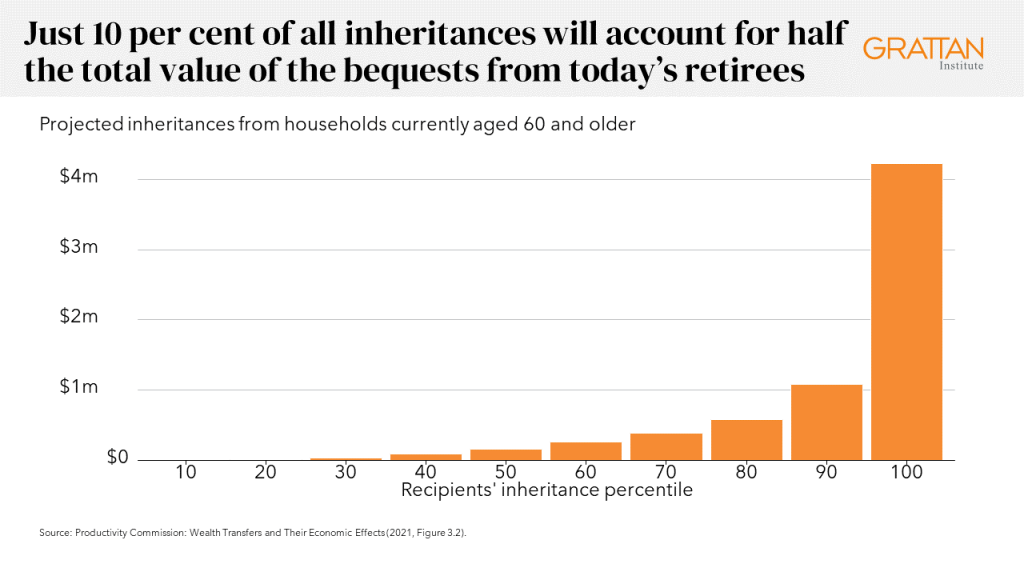

Big inheritances boost the jackpot from the birth lottery. Richer parents tend to have richer children. Among those who received an inheritance over the past decade, the wealthiest 20 per cent received on average three times as much as the poorest 20 per cent.[23]

The Productivity Commission projects that among current retirees, just 10 per cent of all inheritances will account for as much as half the value of bequests.

And inheritances are increasingly coming later in life. As the miracles of modern medicine have extended life expectancy, the age at which children inherit has increased. The most common age to receive an inheritance is late-50s or early-60s – much later than the money is needed to ease the mid-life squeeze of housing and children that Gen Y’s face.[24]

Of course, many parents are also dipping into their savings to help their children into housing now. Indeed, former Reserve Bank Assistant Governor Luci Ellis explained that this is now the only realistic way for many young Australians to enter the housing market.[25]

But this, too, is mainly the domain of the wealthy.

Large intergenerational wealth transfers can change the shape of society. They mean that a person’s economic outcomes relate more to who their parents are than their own talent or hard work.

French economist Thomas Piketty has warned of a “Jane Austen world” where inequality is exacerbated by ever-growing inheritances.

Easing intergenerational inequality means policies that work for the whole generation, not just those lucky enough to have a private safety net.

Part 5 – ‘I’ve paid my taxes’: tales from the frontlines of the intergenerational swindle

‘Demography is destiny’, or so French sociologist Auguste Comte told us.

Every few years the Australian Government releases an Intergenerational Report, reminding us of one facet of this destiny: that, without policy action, an ageing population and other changes will leave public finances looking ugly.

Just last week we had the latest instalment.

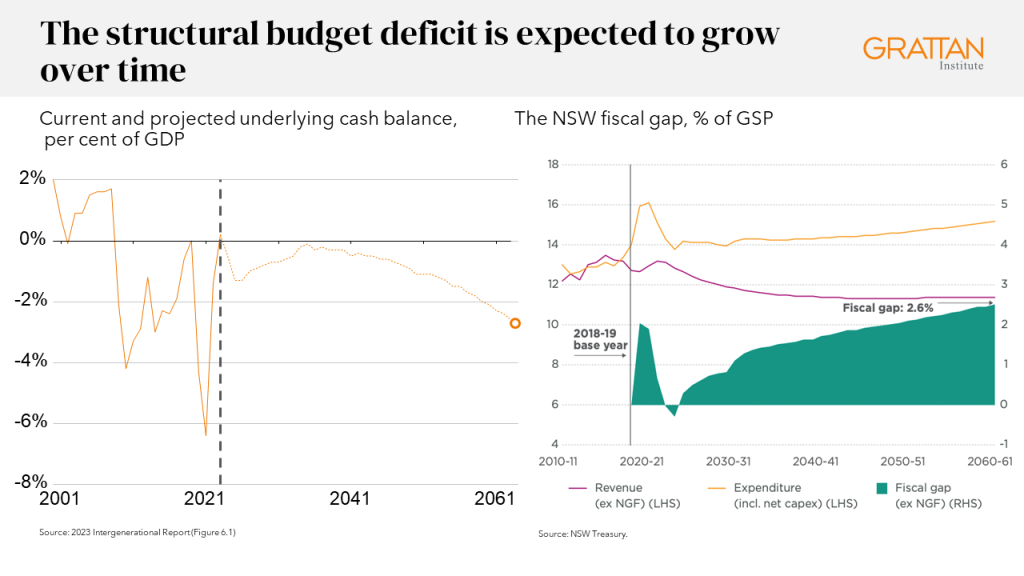

The report highlights that without policy change, budget balances over coming decades will be a sea of red. Net debt will stabilise and fall over the next decade from current highs before starting to creep up again as a share of GDP from the mid-2040s, before rising to around one-quarter of GDP again in the 2060s. Interest payments as a share of GDP will also creep up until reaching 1.4 per cent of GDP in 2062.[26]

The same is true of the position of state governments. Currently NSW is the only state to release its own Intergenerational Report. It suggests that the ‘fiscal gap’ – its gap between revenue and expenditure – will also widen over the coming decades.

Clearly time to put my Back in Black mug back in the back of the cupboard again!

The underlying structural budget challenge comes from the different size of generations and the implicit generational bargain we have weaved into our tax and welfare system.

Working-age Australians, as a group, are net contributors to the budget – they pay more in taxes than they receive in welfare benefits and spending. These contributions support older Australians, who take a lot more out in spending and pension payments than they contribute in taxes.

Today’s working-age Australians of course anticipate that the generation after them will support them in the same way as they age.

So far so fair.

But what will make it more challenging for today’s young people to uphold their end of the bargain is that the destiny of demography is working against them.

The number of working-age Australians for every person aged 65 and older fell from 7.4 in the mid-1970s to 4.4 in 2015, and is projected to fall to just 3.2 in 2055.

This could be seen as just bad luck for today’s young people. There are swings and roundabouts that all generations have had to grapple with.

But what I think is less easy to accept is a series of policy decisions that have substantially increased the size of the intergenerational transfers – supercharging these future demographic pressures.

The size of net transfers – average spending per household minus tax contributions – has grown sharply for older Australians.

There are a range of reasons behind this increase.

First, health spending per person is climbing. Commonwealth health spending per person grew in real terms by about 40 per cent from 2002-03 to 2019-20, and then even faster during COVID.[27] State health spending has also considerably outpaced inflation and population growth over past decades.[28]

Second, aged care spending is also growing strongly.

Australian Government spending on aged care per person more than doubled in real terms over the past 15 years.[29]

These are also areas where strong future growth in spending is anticipated. The main five spending pressures – the NDIS, aged care, interest payments, healthcare, and defence – are all expected to grow by more than 5 per cent a year on average over the next 40 years. In total, spending on the ‘Fast Five’ is expected to grow from 8.8 per cent of GDP today, to 14.4 per cent of GDP by 2062-63.[30]

Most Australians support increased health and aged care spending.

And the result – providing older people with longer, healthier, and more fulfilled lives – is something we should be proud of as a nation.

But at the same time as we have decided as a country to pay more to support better outcomes for older Australians, we have made a series of tax policy decisions – tax-free superannuation income in retirement, refundable franking credits, and special tax offsets for seniors – which mean we now ask older Australians to make a much smaller contribution to the delivery of services than we once did.

Incomes for households over 65 have more than doubled over the past 25 years – substantially faster growth than for households under 55.

But households over 65 pay virtually no more income tax than people of the same age 25 years ago. Indeed, the share of older households paying any income tax fell from 27 per cent in the mid-1990s to 17 per cent pre-COVID.[31]

And that has contributed to a tax system where someone’s date of birth is almost as important as their income in determining their tax contribution.

An older household with income of $100,000 pays about the same tax as a working-age household on $50,000. There is simply no policy justification for this degree of age segregation in the system.[32]

One argument that is sometimes advanced to defend the generosity of age-based tax breaks is that older Australians have “paid their taxes”. But the idea of the tax system as an individual’s piggy bank is silly if you believe in a progressive tax and welfare system and the provision of public goods like roads and defence.

Nor does it hold water in a generational sense. Younger households today are underwriting the living standards of older households to a much greater extent than in the past.

People born in the late-1940s, at the beginning of the Baby Boom generation, reached their peak contribution to the tax system in their early 40s – and at that point they were contributing an average of $3,200 a year in today’s dollars to support older generations in retirement. An average 40-year-old today, born at the tail end of Generation X, is paying $7,300 a year.

That is more than they are contributing to their own retirement through compulsory superannuation.

Under current policy settings, the child of today’s 40-year-old will need to pay an inflation-adjusted $11,400 by the time he or she reaches 40 just to sustain the current levels of benefits in retirement.[33] That’s what the Intergenerational Report reminds us of: that without policy changes we kick the can down the road. Budget deficits are set to grow ever bigger, and net debt will increase as a share of the economy in decades to come.

And these projections rely on income taxes doing the heavy lifting – rising from around 50 per cent of tax receipts today to 58 per cent in 2062-63. And this higher tax will be collected from a narrower base of working Australians.[34]

The unwanted fiscal inheritance will fall on the generation of Australians whose wealth has stagnated – the same generation who missed the property boom or face rapidly escalating costs to service their mortgage.

Part 6 – Code red for our morality

But all of these debates about tax and even house prices seem small compared to the ultimate generational transfer – the impost of a changing climate and the shifting of most of the heavy lifting on mitigation.

Climate-change policy debates come with thorny ethical issues – to what extent should we ‘discount’ future harms from today’s decisions,[35] how do we factor in likely improvements in technology in deciding the right time path for action, how much extra lifting should the developed world do to reflect the fact that we have already reaped the economic benefits from carbon-intensive development?

While these are interesting and important questions, the bottom line is we are a very long way from these grey zones.

The world has not done enough and is unlikely to do enough to keep temperature rises within the 1.5 degrees needed to avert serious and potentially irreversible shifts in environmental systems.

Scientists estimate that at 1.5 degrees – which we are likely to exceed in the next decade – intense heatwaves will happen at four times the historical rate, and droughts and floods at almost twice the historical rate.[36]

Already in 2023, we have seen the hottest month ever recorded (in June), and four consecutive months where global ocean surface temperatures hit a new high. Wildfires ravaged Hawaii in August, another extreme weather event that scientists warn we will see more of.

At rises of 2 degrees, which is on the cards between now and 2050 without much more significant ambition from the world to reduce emissions, bushfires of the magnitude of our disastrous 2019-20 summer will be four times as likely to occur.[37] Also at 2 degrees, only 1 per cent of corals in the Great Barrier Reef will survive.[38]

Large parts of the world will become uninhabitable, and the World Bank predicts there will be 143 million climate refugees by 2050 in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America alone.

It is, in the words of United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, a “code red for humanity”.

And while Australia and most of the world has now committed to a pathway to net zero,[39] the so-far glacial pace of change risks leaving young Australians with both the fallout and most of the hard work of mitigating emissions.

Last week’s Intergenerational Report also laid bare the economic cost facing younger generations. Left unaddressed, the impact of higher temperatures on the way we work will flow through to lower labour productivity, costing us between $135 billion and $423 billion in the long run.[40]

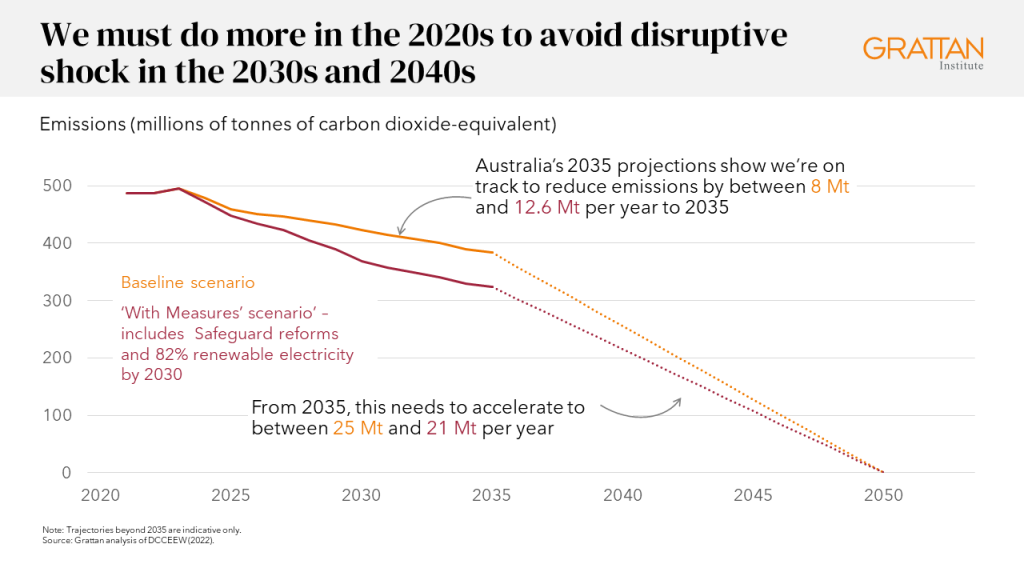

If we look at the current path of emissions reduction – the orange line – emissions are trending downwards but slowly.

Even if we manage to get on the red path that the current federal government has promised – including 82 per cent renewable energy penetration by 2030 and a fully implemented set of Safeguard reforms to reduce industrial emissions – we will still need to up the pace of change for 2035 and beyond.

Indeed, if we do not pick up the pace now, we’ll leave ourselves with a costly and disruptive task to get on the right trajectory through the 2030s and 2040s.

When we look at emissions reductions by sector, the cause of the current challenge is evident.

Emissions are coming down in the electricity sector, although not as fast as we need given the importance of this sector as an emitter and its role in the decarbonisation of other crucial sectors such as transport and industry.

Outside of electricity we have made virtually no progress. We are yet to bend the curve on agriculture, transport, or waste emissions. The government will need to land its Safeguard Mechanism to achieve the projected reductions in industrial emissions.

The scale and pace of change required have led my Grattan Institute colleagues to dub it an industrial revolution – on a deadline.

Against the backdrop of this urgency, I almost fell off my chair a few weeks ago when I heard the leader of one of our major political parties call for a “pause” in the rollout of wind and solar and transmission.[41]

After at least four decades in neutral on climate policy and with the world now boiling, is asking for a little more time for “honest conversations” the best we can do?

Which brings me to the gaping hole at the centre of the debate on climate policy in this country.

Why, despite the tsunami of coverage on the issue, is there virtually no mention the intergenerational case for taking action? Since Kevin Rudd’s response to the ‘greatest moral challenge’ fell over at the first political hurdle, almost no one in power has dared to make reference to the catastrophic impacts of global inaction on our children and their children’s safety, health, economic opportunities, and wellbeing.

Of course these issues are important and relevant, but what should we take from an existential crisis being sliced and diced into an industrial policy debate?

Are we a venal bunch with no care about the future?

I don’t believe this is the case, but our children may be forgiven for thinking so given our action or lack thereof.

We need to do better.

Part 7 – Building better

What would make a better Australia for the next generation is not a simple question.

We should listen to the voice of young people and what they think is needed.

Youth-focused organisations have rightly expressed frustration at not being consulted on the intergenerational Report despite its implications falling squarely on today’s young.

A coalition of youth-organised groups including Think Forward, the Foundation for Young Australians, Youth Action, Youth Development Australia, and the Youth Affairs Councils from several states have called for a parliamentary inquiry to start the conversation on intergenerational fairness.[42]

They take their inspiration from the 2018 House of Lords inquiry in the UK. The report from that inquiry, Tackling Intergenerational Unfairness, was published in 2019 and observes that intergenerational fairness has become an “increasingly pressing concern for both policy makers and the public”.

It found that:[43]

The relationship between older and younger generations is still defined by mutual support and affection. However, the action and inaction of successive governments risks undermining the foundation of this relationship. Many in younger generations are struggling to find secure, well-paid jobs, and secure, affordable housing, while many in older generations risk not receiving the support they need because government after government has failed to plan for a long-term generational timescale.

It all sounds highly familiar.

I reiterate my support for this inquiry and look forward to hearing the ideas presented by those at the frontline of some of the issues I have explored this evening.

Tonight, I want to reflect on some things that my time researching policy suggests to me could make a difference.

First, getting our macroeconomic policy settings right.

Right now we are in the extraordinary position of having an unemployment rate ‘with a 3 in front’.[44] And that has come alongside the fact that a record number of Australians are working.

It means that more people who want a job now have one. It means that some people otherwise at the fringes of the labour market – including young people – are now seeing doors open that previously stayed closed.

If lower unemployment can be preserved as inflation cools, then over time we can expect to see a reversal of the trend from the decade pre-COVID of high youth unemployment and flagging income growth.

This would be a wonderful outcome.

The other debate I think we need to have is whether monetary policy should be the sole item in the policy toolbox to respond to high inflation.

We have relied on the Reserve Bank because of its capacity to act swiftly and without political constraint, and those things are crucial. But the distributional consequences of monetary policy – and particularly the stark generational differences – point to a need to complement monetary policy with fiscal discipline.

Could a new generation of fiscal rules – including those that put a break on new spending or automatically uplift taxes – be put in place with an inflation trigger to help share the burden?

Second, setting up the next generation for success in the new economy.

This means turning around the slump in educational outcomes.

The great news is we know a lot of things that would make a difference.

These include:

- Creating better careers paths and promotional opportunities for top teachers, so we can attract and retain high-achievers in the teaching profession

- Governments procuring high-quality curriculum materials and making them available to all schools should see a banishing of the phenomenon of teachers scouring Instagram at midnight for suggestions for tomorrow’s lesson plan.[45] Using high-quality, school-wide curriculum materials saves time and boosts learning, especially for new teachers and struggling students.

- Using evidence-based instructional techniques would also make a difference to student performance. The Tasmanian government’s recent commitment to lift reading performance through a “minimum guarantee” that reading instruction be done according to the evidence about what works best, is a start.

- To make this a reality, more support is needed for teachers to implement effective instruction in class – better instructional guidance and training for teachers is essential.

- And finally, small-group tutoring should be embedded in all schools to help students who are falling behind to catch up to their classmates. This last initiative is currently happening in NSW and Victoria, giving the other states a model to follow.

Third, refocusing our energy on productivity-enhancing reforms to grow the pie.

There is no shortage of suggestions here – from tax, to planning, to health, to migration – growing productivity will underwrite future improvements in living standards.

The work from federal and some state productivity commissions, various system reviews and, if I can plug my own work, the Grattan Institute, mean that governments have a lot of good ideas to work with.

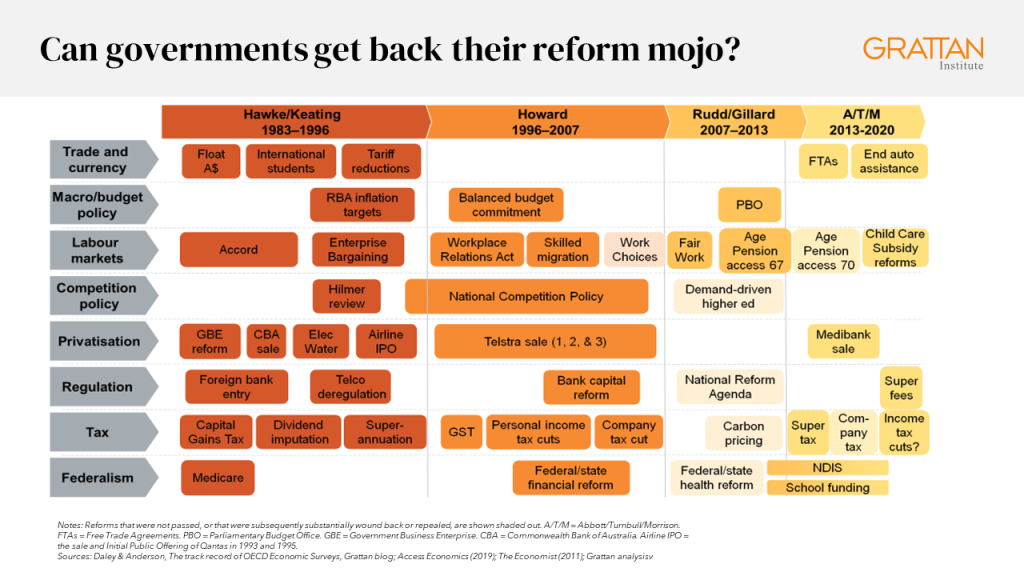

The question is really whether after almost two decades of subdued economic reform ambition – fewer reforms, smaller reforms, and the relatively new phenomenon of ‘reform rollback’ – reforms being introduced but then wound back after a change in government (the light shaded boxes) – whether governments have the appetite or the political capital to pursue some of the more challenging choices.

Fourth, cleaning up the mess that is housing policy.

As outgoing Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe reminds us, the problem here is ‘supply, supply, supply’.[46] But more accurately, supply close to jobs and where people want to live.

The opportunity for some residents in some inner and middle-ring suburbs to frustrate any development in the name of preserving neighbour character is simply another intergenerational transfer that prioritises the needs of existing homeowners over want-to-be residents. This has resulted in younger families being pushed further out to the urban fringes.

National Cabinet has finally put this issue on the national agenda. And its emphasis on encouraging the states to confront the challenging politics of planning reform to boost supply is very welcome.[47]

And while it’s a second-order issue for affordability, addressing taxation of investment housing, particularly the size of the capital gains tax discount, which interacts with negative gearing to allow housing investors to reduce and defer personal income tax, should also be on the list.

As well as costing the public purse in a period when we need more revenue, the size and design of these tax concessions means more houses in the hands of investors rather than homeowners, and more volatility in housing prices.[48]

Fifth, improving outcomes for people who don’t own their homes.

Again, great to see some long-needed changes agreed to at the National Cabinet, including limiting rent increases to once a year and banning no-fault evictions in all states and territories. This will help boost security of tenure in the jurisdictions lagging on renters’ rights.

For those renters doing it toughest, the best thing the government could do is boost Commonwealth Rent Assistance. This payment, which helps vulnerable renters to keep a roof over their heads and still afford other essentials, remains inadequate. The Albanese Government lifted the maximum rate by 15 per cent in the May budget – that should be turned into a 40 per cent rise.[49]

And the Housing Australia Future Fund – which would fund the largest federal investment in social housing in a decade – should be passed by the federal parliament as soon as possible.

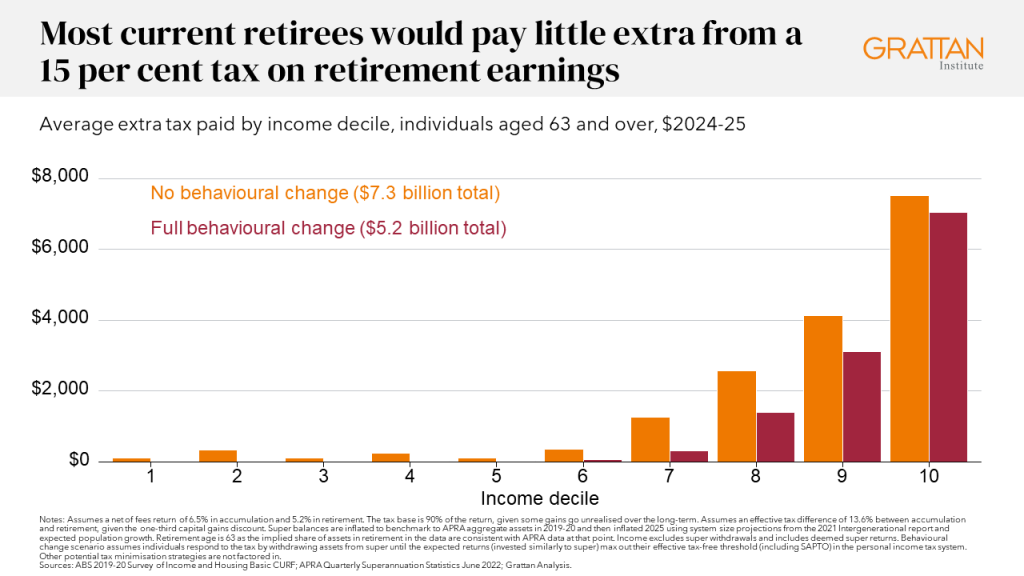

Sixth, winding back aged-based tax breaks by taxing superannuation earnings in retirement at 15 per cent.

This would re-establish the principle that existed pre-Howard, that income tax contributions should be based on income rather than age. And crucially, it would represent a de-escalation of policy decisions that cumulatively ask working-age Australians to underwrite much larger transfers to older Australians than any previous generation has supported.

This simple change would save the budget at least $5.3 billion a year, and much more in future.

The top 10 per cent of retirees by income would pay an extra $7,000-to-$7,500 a year on average, whereas the poorest half of all retirees would pay no more than an extra $200 each, and would stand to benefit much more from the increase in health and aged care spending these revenues could fund.[50]

Seven, seriously grapple with taxes on intergenerational transfers.

While so-called ‘death taxes’, but more correctly ‘intergenerational transfer taxes’, are political dynamite, the windfall wealth gains of older generations and structural budget pressures mean we should at least have a sensible conversation about the possibility about taxing large inheritances.

As former Finance Department official – and Tasmanian – Jo Roach has demonstrated, if the money collected from such a tax were used to fund income tax cuts, most people under 50 would be ahead financially.[51]

At a minimum, we should not be subsiding inheritances via some of the existing rules that allow the accumulated value of superannuation tax breaks to be inherited by the next generation, as well as the exclusion of virtually all the value of the family home from the Age Pension assets test.[52]

Finally, Australia needs to get on with the job of emissions reductions across the economy.

Ideally, that would mean embracing first-best policy and putting in place a tax on carbon emissions. But even if we don’t go there, there are a range of sector-based policies that could make a difference.

It will require pushing hard to meet the ambitious target of 82 per cent renewables penetration by 2030. It means picking some of the low-hanging fruit that exists, like an emissions standard for vehicles.

If governments are looking for inspiration, the recent Grattan Institute ‘Net Zero’ series is filled with evidence-based suggestions of relatively low-cost things we could do right now that would help put Australia on the right trajectory.

The alternative is we continue to be part of the problem rather than the solution to this generational, indeed existential, global challenge.

Part 8 – Calling time on generation warfare

I understand my comments today are strong, and my policy suggestions might feel confronting.

I may be accused of trying to whip-up generational conflict. But, let me be clear, that is the exact opposite of what I hope to achieve.

I believe that most Australians care deeply for other generations and want to restore the generational bargain.

For all the Gen Z ‘OK Boomer’ eye rolling, young Australians gave up their social lives and in some cases their jobs to protect the welfare of the older and more vulnerable Australians during COVID. Polling throughout the pandemic suggested young Australians were more strongly in favour of lockdowns than any other age group.

And for all the pious Boomer lectures about brunch choices, much of the concern I hear about house prices and their impacts actually come from the older generations, many of whom say they would be happy to see the prices of their own assets reduced to ease the pressure on future generations.

Similarly, look around any climate change lecture or protest, and you will find grey-haired attendees as common as tattooed ones in the crowd. Care about the future is alive and well. A proper debate about the impacts of policy settings on the outcomes for different generations can only occur when we reject once and for all ‘generational exceptionalism’: the damaging belief that differences in life outcomes between generations are driven by differences in work ethic, talent, or attitude, rather than luck and policy choices.

American political philosopher Michael Sandel notes how such belief systems corrode civic sensibilities:

For the more we think of ourselves as self-made and self-sufficient, the harder it is to learn gratitude and humility… And without these sentiments, it is hard to care for the common good.[53]

While every generation has its own unique challenges and opportunities, the only rational place to start is the idea that people born at different points in time are no less deserving than others.

So let’s drop the petty generational warfare, and work together to ensure that the Australia we leave to our children is better than the one we inherited. With the right policy settings, I believe we can restore the hopeful bargain.

Footnotes

- Hytten, T. (1951), “Lyndhurst Giblin: Note on His Influence on Australian Political Economy”, The Australian Quarterly, 23.2, pp. 67-70.

- Ibid, p. 68 .

- Brigden, J. B., Copland, D. B., Dyason, E. C. , Giblin, L. F., Wickens, C. H. (1930), “The Australian Tariff: An Economic Inquiry”, Economica, 30, pp. 328-330.

- Pew Research Centre (2022), Large shares in many countries are pessimistic about the next generation’s financial future.

- Scape (2023), Gen Z Wellbeing Index.

- Although the RBA recently noted that increased hours or work and job-switching activity has led to total employment income growth being stronger than base wages, particuarly for low-income earners. See: Chart 4.29, Statement on Monetary Policy – August 2023, Reserve Bank of Australia.

- Wood, D., Chan, I., and Coates, B. Forthcoming presentation to RBA conference.

- Budget Direct (2019), The financial strain on Australian’s pockets

- Lowe., P. (2023), Appearance before the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics on 11 August 2023.

- The flip side advantage of inflation is to erode the real value of mortgage principals, reducing the time taken to repay loans.

- Grattan analysis of the 2019-20 ABS Survey of Income and Housing microdata and Productivity Commission (2019), Assessing the Efficiency and Competitiveness of the Superannuation System: Technical Supplement 4, Table 4.20.

- See for example: Windsor, C., Jääskelä, J., and Finlay, R. (2013), Home Prices and Household Spending, RBA Research Discussion Paper 2013-04; Gillitzer, C., and Wang, J.C., (2015), Housing Wealth Effects: Cross-sectional Evidence from New Vehicle Registrations, RBA Research Discussion Paper 2015-08; and May, D., Nodari, G., and Rees, D., (2019). Wealth and Consumption, RBA Bulletin March 2019. Other channels for interest rates, such as the savings and investment channel and the exchange rate channel, are less likely to have obvious aged-based distributional effects.

- Commbank iQ (2023), Cost of Living Insights Report. Although these data also capture movements from and to external savings accounts.

- National Skills Commission (2022), Employment Projections.

- Ibid.

- The numeracy gap is 2.75 years. This is below the national average of four years pictured, but only because the maths achievement of advantaged Tasmanian students is a year behind the achievement of their peers in other states.

- Kamenetz, A. (2013), Bill Gates on education: we can make massive strides, Fast Company.

- Kryger, T. (2009), Home ownership in Australia – data and trends, Department of Parliamentary Services Research Paper.

- Eslake, S. (2021), Housing affordability and home ownership. Submission to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Tax and Revenue’s inquiry into housing affordability and supply.

- Coates, B. (2022), The Great Australian Nightmare. Grattan Institute

- Coates, B. (2022), The Great Australian Nightmare. Grattan Institute

- Grattan analysis of the ABS National Accounts (March 2023, Table 35: Household Balance Sheet) and ABS Consumer Price Index (June 2023).

- Wood, D., Griffiths, K., and Emslie, O. (2019). Generation gap: ensuring a fair go for younger Australians. Grattan Institute.

- Ibid.

- Adams, D. (2021), The best bet for young people who want to buy a home is to have parents who already own one, the Reserve Bank has admitted. Business Insider Australia.

- Commonwealth of Australia (2023), Intergenerational Report: Australia over the next 40 years.

- Commonwealth of Australia (2023), Intergenerational Report: Australia over the next 40 years.

- Daley, J. and Wood, D. (2014), The Wealth of Generations, Grattan Institute.

- Commonwealth of Australia (2023), Intergenerational Report: Australia over the next 40 years.

- Commonwealth of Australia (2023), Intergenerational Report: Australia over the next 40 years.

- Wood, D. and Griffiths, K. (2019), Generation gap: ensuring a fair go for younger Australians, Grattan Institute. The 2023 Intergenerational Report estimates that 12 per cent of Australians aged over 70 pay any income tax. See: Commonwealth of Australia (2023), Intergenerational Report: Australia over the next 40 years.

- Daley, J. and Wood, D. (2014), The Wealth of Generations, Grattan Institute.

- Ibid.

- Commonwealth of Australia (2023), Intergenerational Report: Australia over the next 40 years

- Economists typically use a discount rate to compare a stream of costs and benefits over time – to recognise that people generally prefer benefits today over the same benefits in the future.

- Milman, O., Witherspoon, A., Liu, R., and Chang, A. (2021), The climate disaster is here, The Guardian; Levin, K. (2018), Half a Degree and a World Apart: The Difference in Climate Impacts Between 1.5˚C and 2˚C of Warming, World Resources Institute.

- Milman, O., Witherspoon, A., Liu, R., and Chang, A. (2021), The climate disaster is here, The Guardian.

- Australian Academy of Science (2021), The risks to Australia of a 30C warmer world.

- 138 countries have committed to net zero by 2050. China has committed to net zero by 2060. This means that 88% of global emissions are now covered by net zero targets. See: Net Zero Tracker.

- Commonwealth of Australia (2023), Intergenerational Report: Australia over the next 40 years.

- David Littleproud, Insiders interview, ABC, Sunday 13 August 2023.

- Think Forward (n.d.), We urgently need a parliamentary inquiry into intergenerational fairness.

- UK Parliament, House of Lords, Select Committee on Intergenerational Fairness and Provision (2019), Tackling intergenerational unfairness.

- ABS Labour Force (July 2023).

- Hunter, J., Haywood, A. and Parkinson, N. (2022), Ending the lesson lottery: How to improve curriculum planning in schools. Grattan Institute.

- McHugh, F. (2023), Philip Lowe wants you to get more flatmates to help solve the rental crisis. SBS News.

- The incentive payment will give jurisdictions $15,000 for every home delivered above the old target of 1 million homes over five years from July 2024. See: Albanese, A. (2023), Press Conference – National Cabinet – Brisbane.

- Daley, J. and Wood, D. (2016), Hot property: Negative gearing and capital gains tax reform. Grattan Institute.

- Coates, B. and Moloney, J. (2023), Why freezing rents would do more harm than good. Grattan Institute.

- Coates, B. (2023), How super tax breaks should be reformed. Grattan Institute.

- Materials provided by Joe Roach to Grattan Institute.

- For more detail see: Wood, D., Griffiths, K., and Emslie, O. (2019), Generation gap: ensuring a fair go for younger Australians. Grattan Institute.

- Sandel M. (2021), The Tyranny of Merit. Penguin Press.

While you’re here…

Grattan Institute is an independent not-for-profit think tank. We don’t take money from political parties or vested interests. Yet we believe in free access to information. All our research is available online, so that more people can benefit from our work.

Which is why we rely on donations from readers like you, so that we can continue our nation-changing research without fear or favour. Your support enables Grattan to improve the lives of all Australians.

Donate now.

Danielle Wood – CEO