Thank you to everyone for joining us.

Tonight I’m speaking on the lands of the Wurundjeri people and I would like to acknowledge them and pay my respects to their elders past, present, and emerging.

The traditional owners of the lands that we now call Australia understand better than any of us the importance of land in a society. Before European settlement, the reciprocal relationship between people and land underpinned all other aspects of life for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

That connection to land remains fundamental to their health, their relationships, and their culture and identity. It’s why I hope that we will soon see constitutional reforms to empower indigenous Australians to, in the words of the Uluru Statement of the Heart, take their rightful place in what has always been their country.

I was delighted to be invited to give what is the 131st Annual Henry George Commemorative Lecture tonight. Thank you to Prosper for the invitation to do so. I’ve worked closely with Prosper to support effective tax policies, such as Victoria’s recent windfall gains tax on property rezonings. Prosper plays a unique role in Australian public life in reminding Australians of the importance of land.

Tonight, I also want to talk about land, and the way rising house and land values sits at the heart of some of Australia’s most pressing policy challenges.

One man who did understand the economic value of land was Henry George, whose life and work we are here to honour tonight. Henry George is best known for his advocacy of a single tax on the unimproved value of all privately held land.

`One of the key messages from tonight is that Australia would have done well – possibly much better than we have done – if we’d heeded the lessons of Henry George and paid more attention to the economics of land.

Because upstream from the Great Australian Nightmare of worsening housing affordability –and all the downstream consequences it is creating in our society – sits our longstanding intellectual neglect of the economics of land.

Part 1 – How economists came to ignore land

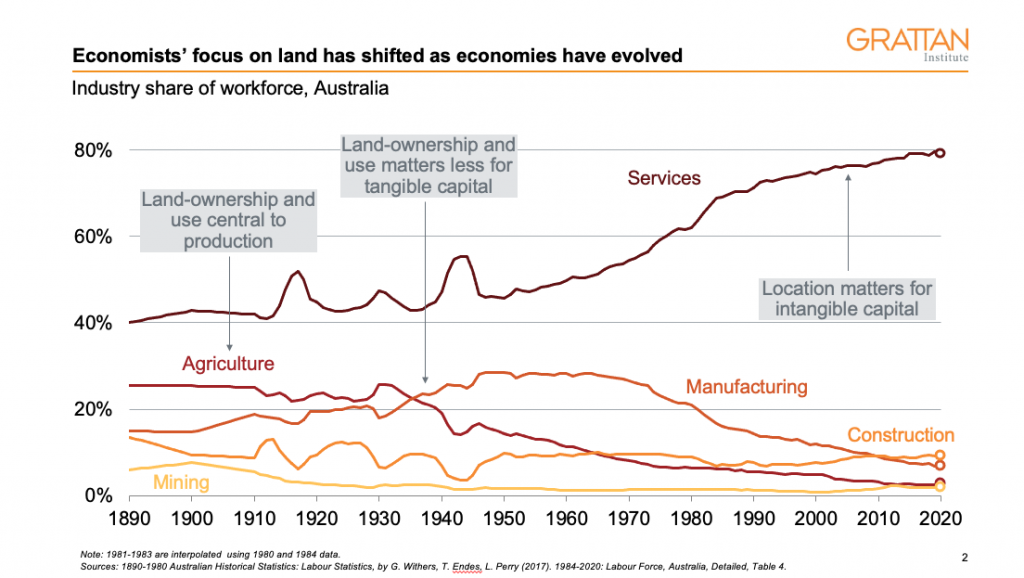

Economists’ interest in land has waxed and waned over time.[1] For the political economists of the 18th and 19th centuries, it was central to our understanding of the world. They believed that the distribution of rents from land ownership could explain the yawning gaps between the rich and poor, among many other economic ills.

The very first economists – the Physiocrats – thought of almost nothing else.

Land was fundamental – agricultural labourers were the source of economic growth, while landlords simply commandeered their product and flowed it through the rest of the economy.

The next generation of classical economists broadened their focus to the complex interactions of land, capital, and labour.

Adam Smith argued that the division of labour and technological progress drove growth. But land was still central.

David Ricardo argued that landlords are simply the lucky beneficiaries of land’s natural scarcity and productive capacity. Thomas Malthus famously, albeit erroneously, thought that land’s inherent scarcity put an immovable constraint on economic progress.

And Henry George – often thought of as the last classical economist, and the thinker we are here to pay tribute to tonight – argued that the rents enjoyed by landlords must be socialised by taxing land values.

In the 20th century, neo-classical economists changed tack. Robert’s Solow’s landmark theory of economic growth posited that it was the improvements in the efficiency of how capital and labour combined that drove living standards. Land was not a distinct feature of the model.[2]

The role of land in production and inequality disappeared from the theories economists devised to explain the world. Instead, land is treated like any other form of capital, and the windfall gains that naturally accrue to landowners in a growing economy – generally referred to as “land rents” – have been allowed to grow.

The neglect of the economics of land in economics in recent decades has left us poorly placed to deal with some of the challenges arising from rapidly increasing land values today – an issue I’ll return to shortly.

In many ways, this shifting focus on land in the history of economic thought reflects the changing nature of the economies that economists were trying to explain.

The Physiocrats observed a world dominated by agriculture, where it would have been self-evident that the ownership and use of land determined what got produced, in what quantities, and who got it.

Classical economists watched this world transition through the industrial revolution, and neo-classical economists developed theories for a world that had transitioned.

Economic power started to gravitate towards those who owned capital, and away from those who owned land. Agricultural production made way for industrial production.

For most of the 20th century, the neglect of land was of little consequence. For economies powered by manufacturing, who owned land, where it was, and how it was used, was of secondary importance to the amount of capital invested and the pace of technological innovation.

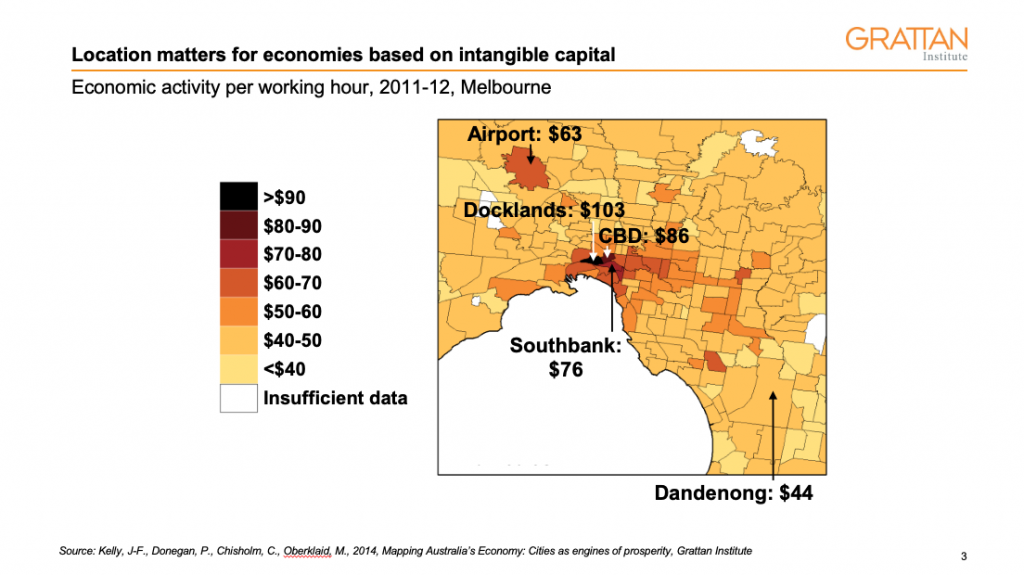

But as the advanced economies of the world have transitioned again – from manufacturing to services – land is back. Economies powered by intangible capital strive or stagnate based on the ability of individuals to come together and combine their knowledge and skills. It is, as any real estate agent would tell you, all about ‘location, location, location’.

Grattan Institute work shows that cities are the economic engines of the modern economy. Eighty per cent of the value of all goods and services produced in Australia is generated on just 0.2 per cent of the land. Economic activity is concentrated in CBDs, with those of Sydney and Melbourne accounting for 10 per cent of all economic activity in Australia – more than three times the contribution of the entire agricultural sector.[3]

This concentration reflects the rise in knowledge-intensive services, clustered together at the hearts of our major cities. That fact that businesses are willing to pay high rents to locate in the CBDs of our major cities shows the value of having access to high-skilled workers and proximity to suppliers, customers, and partners in those scarce locations.

And the willingness of Australian workers to pay much higher house prices for homes located close to those employment centres shows that Australians also see value in these connections.

Now of course the experience of COVID has reversed this trend a little. We’ve learnt that remote work isn’t that bad. We’ve all learnt how to use Zoom, although perhaps unsurprisingly many of us still struggle at times with Microsoft Teams.

Patterns of settlement and work have shifted a little as people moved further away from the CBDs of our major cities to make use of the opportunity to work from home, to work from the beach, or wherever else they want.

But even this process has limits. Most knowledge businesses appear to have settled on a form of hybrid work where workers are in the office part of the week. And land towards the centres of Australian cities remains scarce, and valuable.

Part 2 – A nation of millionaires

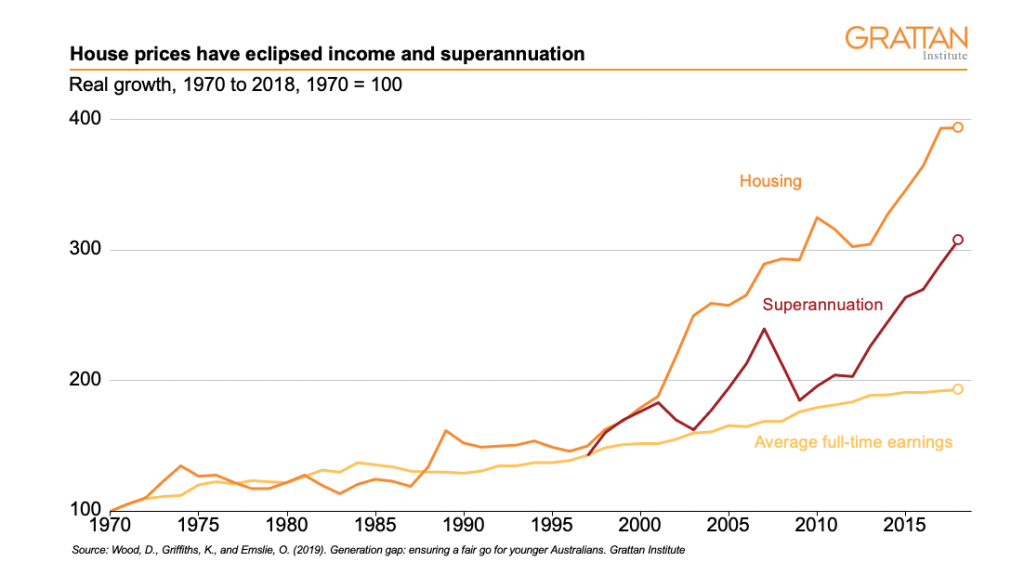

In the past few decades, house prices have skyrocketed. While average full-time earnings have doubled over the past half century, house prices have quadrupled.

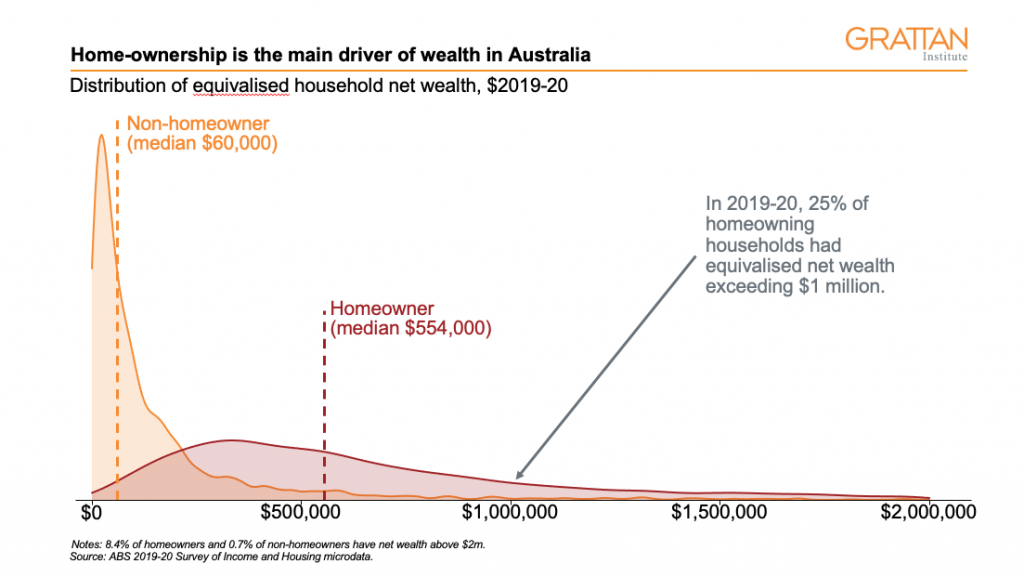

Today the rising value of land, mostly in the form of housing, has turned Australia into a nation of millionaries.

The total value of housing in Australia now totals nearly $10 trillion, out of total household wealth of $14.9 trillion.[4] The average net wealth of Australian households was $1.04 million in 2019-20. Fully one quarter of homeowning households reported net wealth exceeding $1 million, while the typical homeowner reported wealth in housing of $554,000.[5]

Rising asset prices over the past 2 years, albeit now starting to reverse, mean this figure is almost certainly higher now.

The huge increases in home prices relative to incomes in advanced economies in the post-war period has mainly been driven by rising land values, accounting for around 80 per cent of growth since the 1950s on average, with construction and replacement costs increasing only at the rate of inflation.[6]

Now think about your house, if you own one. Your shelter, the place you return home to. I’m sure you’ve spent some time on maintenance and upkeep. But unless you are featuring in the next season of Grand Designs, I’m guessing it consumed substantially less of your time and energy than your job did.[7]

Yet economists Josh Ryan-Collins and Cameron Murray estimate that prior to June 2019, in 16 of the previous 29 quarters the median Sydney home earnt more than the median full-time worker. How can it be that a relatively low risk, low effort investment can often provide greater returns than a year of hard work?[8]

And here we see how the fact that land was neglected in public discourse for so long has proven so costly as the Australian public, via their governments, have been among the smallest beneficiaries.

Australian governments derive far less revenue from property taxes as a share of GDP than they should. Australia’s property tax take – at less than 1 per cent of GDP — is far below that of some comparable countries. Land taxes do not distort decisions about land use, provided they apply in a way that the landowner can’t avoid. Which is precisely why economists hold land taxes in such high regard.

But at the same time, no country has succeeded in collecting a large share of land rents via land taxes, as Henry George demanded. Land taxes have in fact proved to be unpopular because they are highly salient – hitting the cash flows of households and businesses each year. In contrast stamp duties, which are almost universally denounced by economists because they impose large economic costs, have proven to be more palatable to the public.

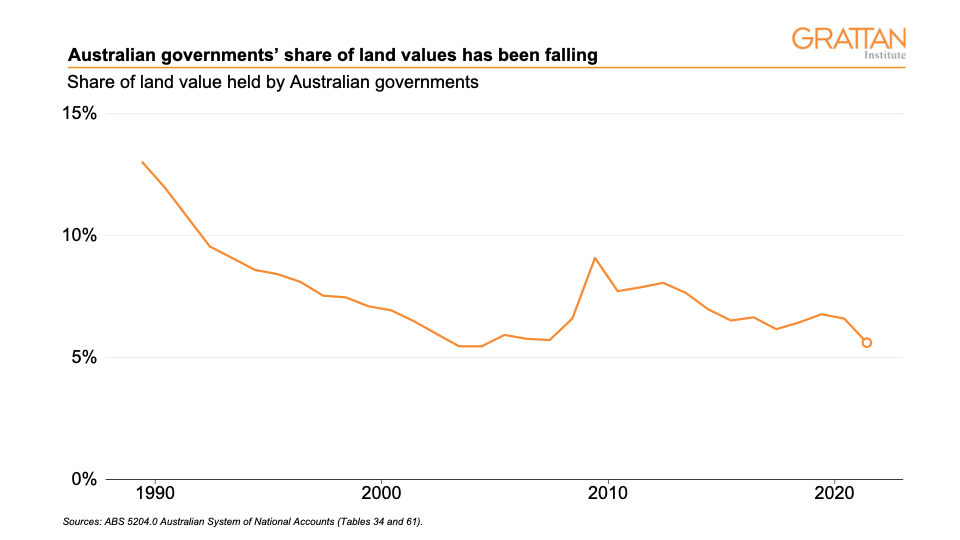

Many countries were lucky enough to capture a good share of the rapid rise in land rents in recent decades because they owned a lot of land. In contrast Australian governments own relatively little land – just 6 per cent of total land value in Australia today. This means these growing returns to housing are captured privately, and our governments are limited in their ability to share these spoils with those that don’t own housing and land in ways that other countries have done, such as Singapore.

Part 3 – The drivers of rising house (and land) values

But what’s driven the enormous rise in house values since the Second World War?

It’s a story of historically low interest rates, increased access to finance, tax and welfare settings that favour investments in housing, and a boom in migration that’s led to a chronic shortage of housing.

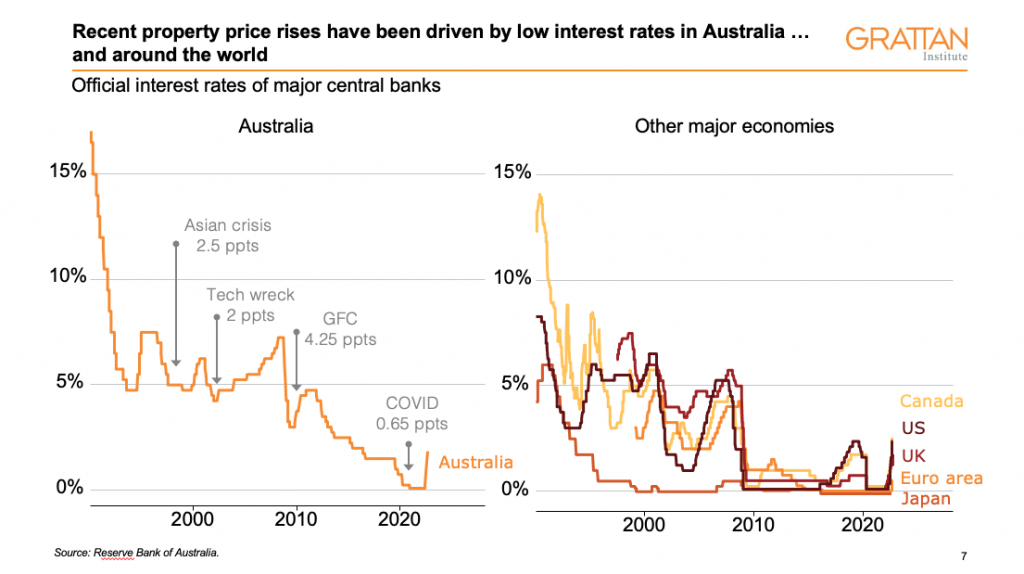

Housing is both something we live in and an asset we own that we borrow money to buy. Which is why it’s no surprise that record-low interest rates have been the strongest driver of rising prices in recent years.[9]

Over the past three decades, interest rates have fallen dramatically, here and abroad. This makes people comfortable borrowing more, and banks more comfortable lending it to them. Everyone shows up to the auction with more firepower.

Our experience of COVID reinforced this lesson: house prices soared by more than 20 per cent nationwide even as Australia’s international borders remained closed.

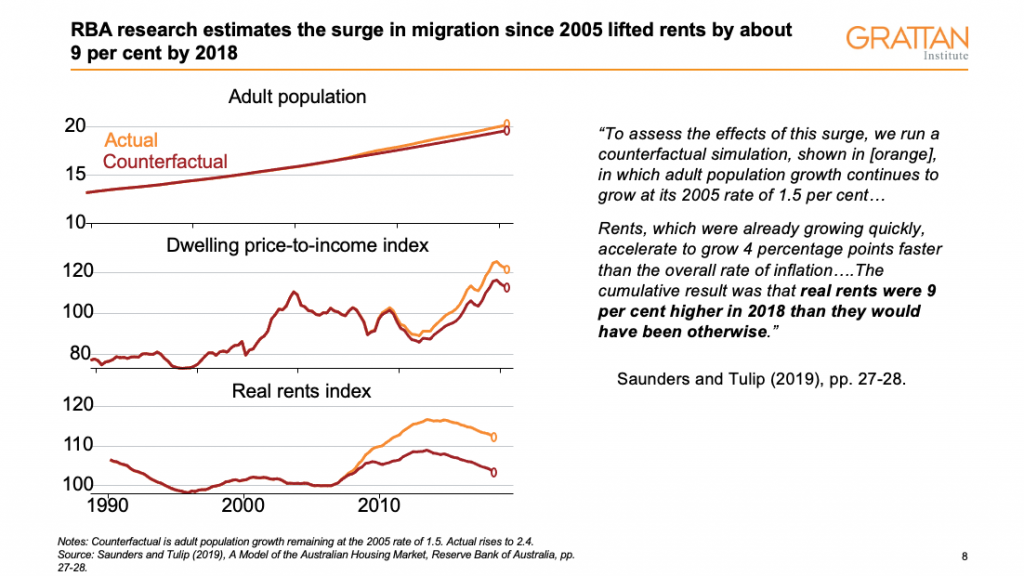

The post-2005 surge in migration also led to dramatically more Australians needing somewhere to live. Reserve Bank researchers estimate that the high migration in the first decade of this century resulted in housing rents being 9 per cent higher by 2018 than they would have been if population growth had stayed at 2005 levels.[10]

Housing demand from extra immigration shouldn’t lead to higher prices if enough dwellings are built quickly and at low cost.

Past episodes of rising housing demand did not see such rapid increases in house prices. Rapid population growth in Australia in the 1950s was matched by record rates of homebuilding.[11] House prices barely moved. Similarly, the post-war expansion of mortgage credit in the United States led to more houses but not higher house prices.[12]

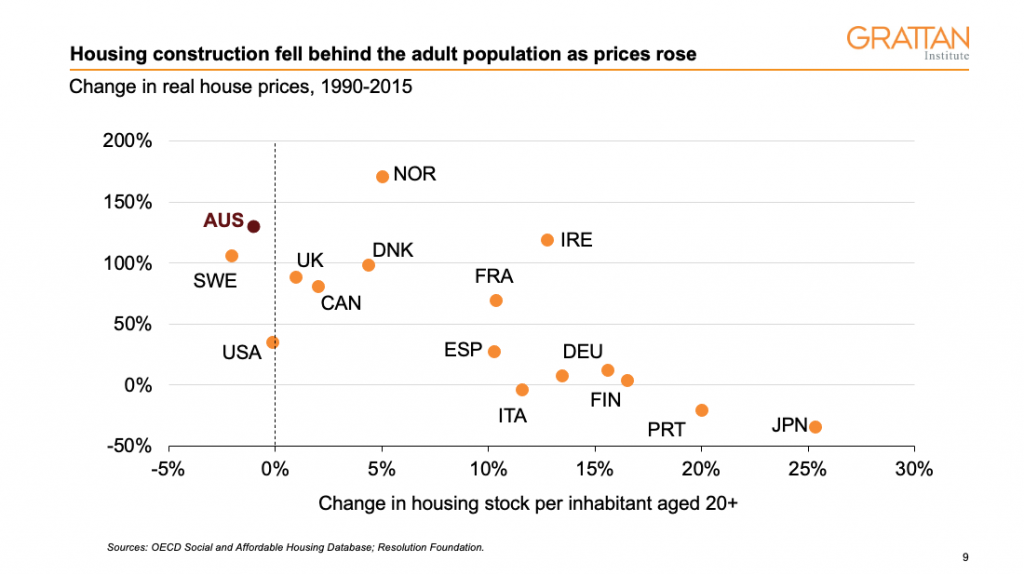

But housing construction in Australia in recent years hasn’t kept up with increasing demand.

Heading into the COVID pandemic, Australia had just over 400 dwellings per 1,000 people, which was among the least housing stock per adult in the developed world. Australia had also experienced the second greatest decline in housing stock relative to the adult population over the 20 years leading into COVID.[13]

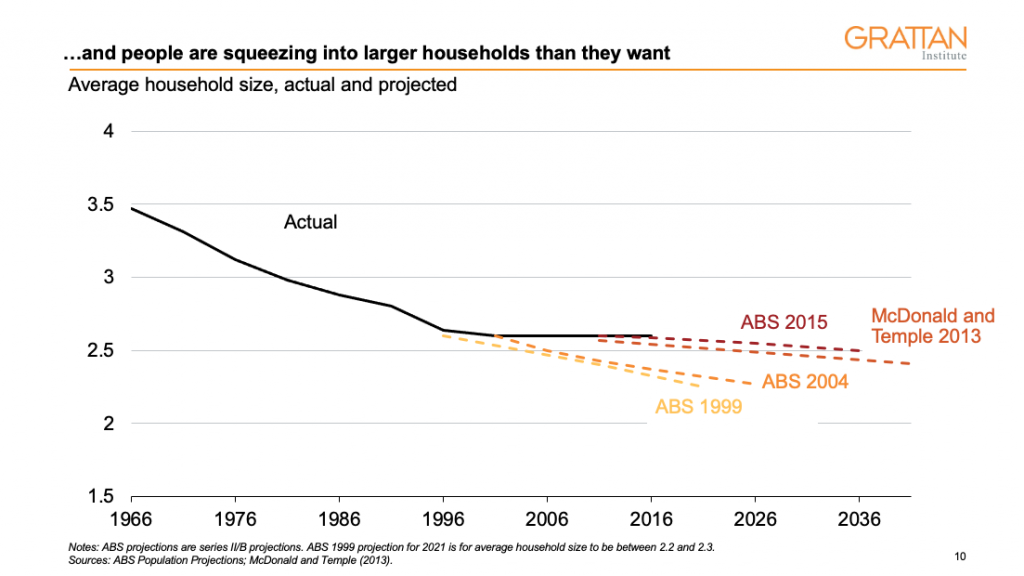

Much of Australia’s unmet housing demand is hidden by the fact that scarce housing has forced people into living in bigger households than they want. Between 1966 and 1996, the typical number of people in a household in Australia fell from 3.5 to 2.6, as couples had fewer children, and higher rates of divorce and an ageing population led to smaller household sizes.

However, declines in average household size have stalled since the late 1990s. Younger Australians are starting households later, and this is most pronounced in the cities where housing is most expensive.[14]

Nor, in my view, is the idea that there is a ‘housing shortage’ contradicted by the existence of more than one million vacant dwellings, as recorded by the 2021 Census, or by Prosper’s work tracking vacant dwellings using data on homes’ water usage.

Census data suggest that the share of vacant dwellings has actually fallen since 2016 and has increased only slightly over recent decades.[15] Some states have sought to introduce vacant property taxes to encourage more vacant dwellings onto the market. But to date no vacant property tax has been successful, since they inevitably include exemptions for uses such as holiday homes, which make them easy to game.

But what impact have COVID border closures had on this story?

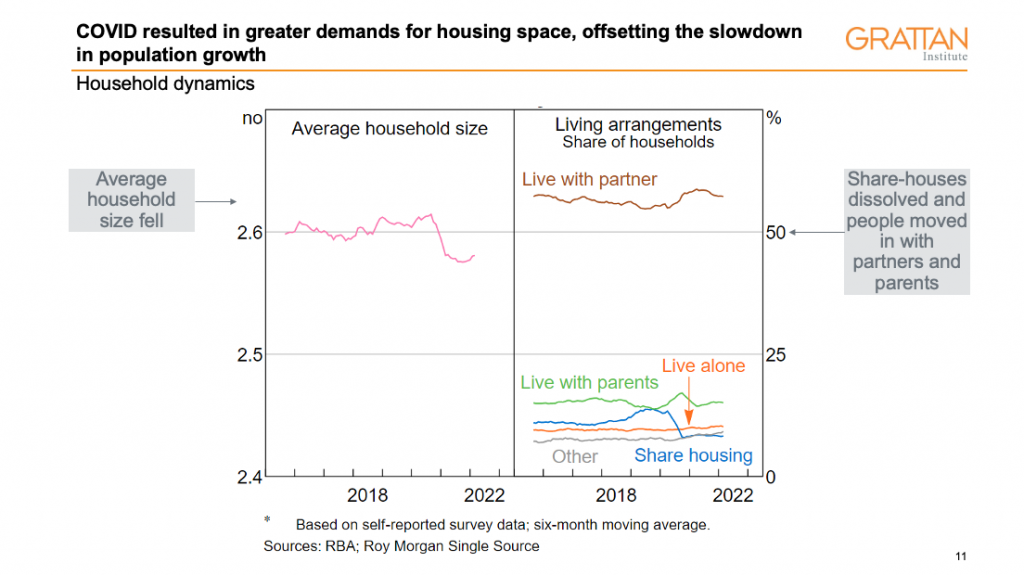

Australia’s population growth slowed sharply during the COVID pandemic thanks to international border closures – over the past two years 200,000 households that otherwise would have migrated to Australia didn’t come.

But this temporary pause in migration did not free up housing stock. With many people feeling the need for more living space during the pandemic, the average size of households shrank. The Reserve Bank of Australia estimates that this trend created demand for an extra 140,000 homes, thus offsetting the fall in population growth.

Advertised rents are already surging, and many of Australia’s most vulnerable are suffering as a result. Less than 1 per cent of rental properties are currently vacant – the lowest level on record.[16] The typical asking rent on a new property is up nearly 14 per cent nationally over the past year.[17] The regions are not immune either, with the work-from-home revolution driving an exodus from the cities, pushing many in regional areas into acute rental stress and homelessness.[18] And now that borders have reopened, population growth, and housing demand, is expected to rebound sharply.[19]

This is largely a failure of housing policy, not housing markets.

Australia’s land-use planning rules are highly prescriptive and complex.

The prices of new homes, including apartments, exceed the cost of building more of them. Reserve Bank researchers estimated that restrictive land-use planning rules add up to 40 per cent to the price of houses in Sydney and Melbourne, up sharply from 15 years ago. More recent research suggests that planning rules have added substantially to the cost of apartments, where building height limits in and around the urban cores of our major cities prevent more construction.[20]

There are reasons to think of these estimates as upper-bound estimates of the size of the impact of land use planning.[21]

But they are consistent with a growing international literature highlighting how land-use planning rules – including zoning, other regulations, and lengthy development approval processes – have reduced the ability of many housing markets to respond to growing demand, adding to both rent and house price growth in a number of countries.[22] In many of these studies we see a clear correlation between the size of land rents and decent measures of land use planning stringency across US cities.[23]

The key problem is that many states and local governments restrict medium- and high-density developments to appease local residents concerned about road congestion, parking problems, and damage to neighbourhood character. The politics of land-use planning – what gets built and where – favour those who oppose change. The people who might live in new housing – were it to be built – don’t get a say.

That is not to say that considerations of land-use planning are entirely spurious. Land-use planning rules set out how competing land uses should be managed to minimise the so-called externality costs produced by some land users – such as pollution, noise, congestion, or poorly planned or poor-quality development. We need those rules. They ensure we don’t build abattoirs next to schools or apartment buildings, benefitting other land users by preserving the amenity of existing residents.

But studies assessing the local costs and benefits of current rules generally conclude that the negative externalities are much smaller than the costs of existing regulations.[24]

Heritage protection is a particular form of planning regulation that slows or stops development. Research from the US has identified an over-emphasis on heritage considerations as a significant barrier to development. While the precise magnitude of the barrier in Australian cities is unclear – no similar study has yet been undertaken – examples abound.

Protecting certain sites under heritage restrictions may be important to the extent that they enrich our understanding of history. But it is often done with little acknowledgement of the costs of conserving heritage sites, which includes stymieing the supply of housing in areas where people most want to live.

More recent work by Prosper and others has shown that land development is prone to cycles and strategic behaviour in greenfield areas.[25] The issue of land banking by developers warrants further investigation, but it does not, in my view, imply that there is a natural ‘speed limit’ on development independent of external constraints on housing supply.

There are many players in the land development market, especially for the urban infill in our major cities that now accounts for more than half of all new housing construction. If developers are land banking on the urban fringe, that housing construction could be offset by more housing construction in infill areas, if land-use planning rules would permit it.

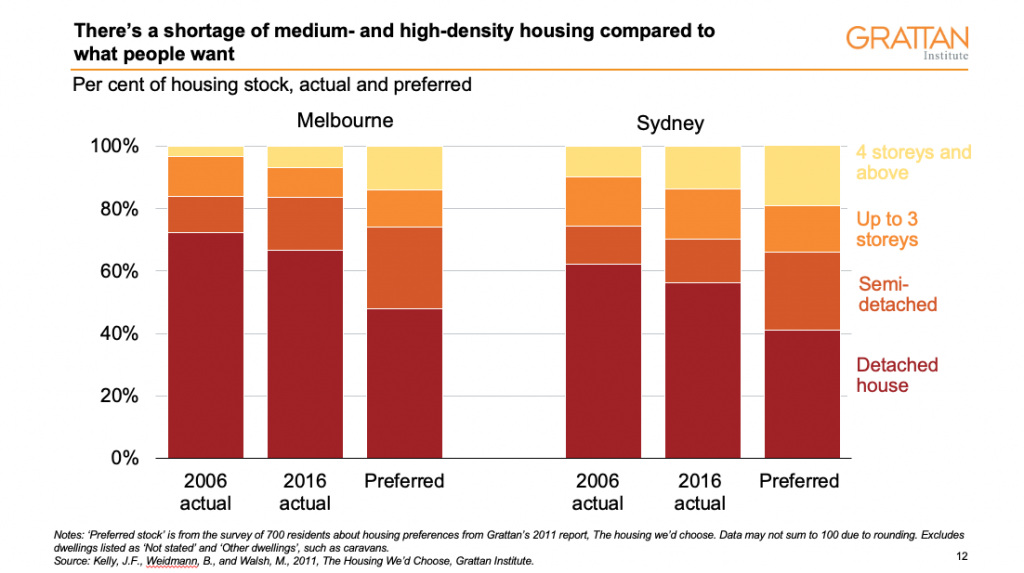

Yet it remains clear cities offer too little medium-density housing in their inner and middle rings. Australian capital cities are more sparsely populated than cities of similar size in other developed economies.

This is not what most Australians want. It is a myth that all new first-home buyers want a quarter-acre block. Many would prefer a townhouse, semi-detached dwelling, or apartment in an inner or middle suburb, rather than a house on the city fringe.

The stock of smaller dwellings – townhouses, apartments, etc – made up 44 per cent of Sydney’s houses in 2016, and 33 per cent of Melbourne’s. Yet, Australians say they actually want those numbers to be 59 per cent in Sydney and 52 per cent in Melbourne.

Part 4 – The Great Australian Nightmare

Within living memory, Australia was a place where housing costs were manageable, and people of all ages and incomes had a reasonable chance to own a home with good access to jobs. But the great Australian dream of home ownership is rapidly turning into a nightmare for many young Australians.

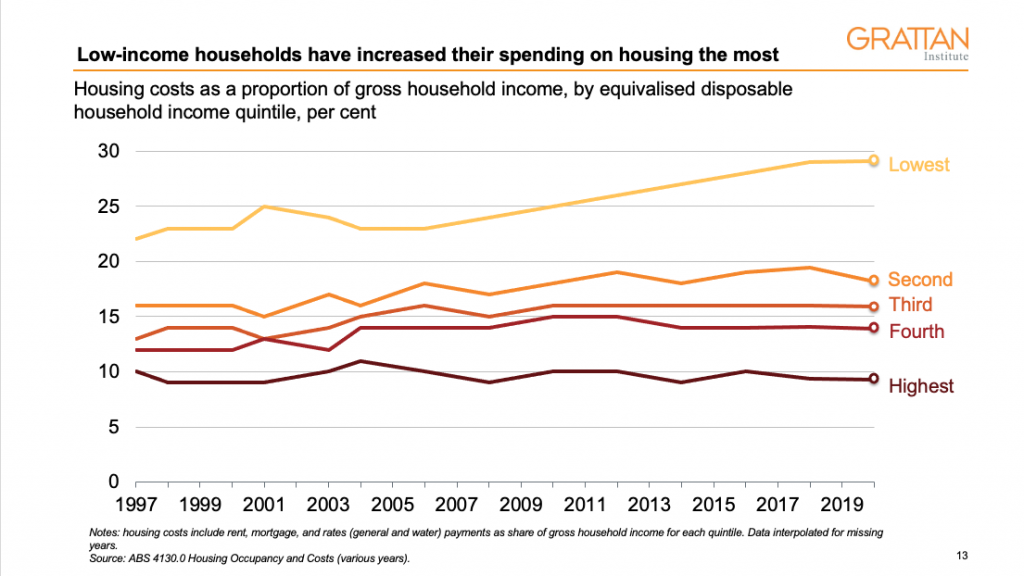

People on low incomes – increasingly renters – are spending more of their income on housing, especially in the form of rent. More than half of low-income Australians in the private rental market suffer rental stress, especially those in the capital cities.

One in five working-aged households who rent are in financial stress, defined as skipping a meal, using charity, pawning something, or not heating the home. The ugliest outcome from this imbalance is simply more people without a home. The number of homeless Australians relative to population ticked up from 2006 to 2016.[26]

Since World War 2, Australia has been a nation of homeowners. Home ownership rates peaked at more than 71 per cent in 1966. Almost three quarters of the nation was on the property ladder and living the dream – home ownership was celebrated as an indicator of success, security, and quality of life.

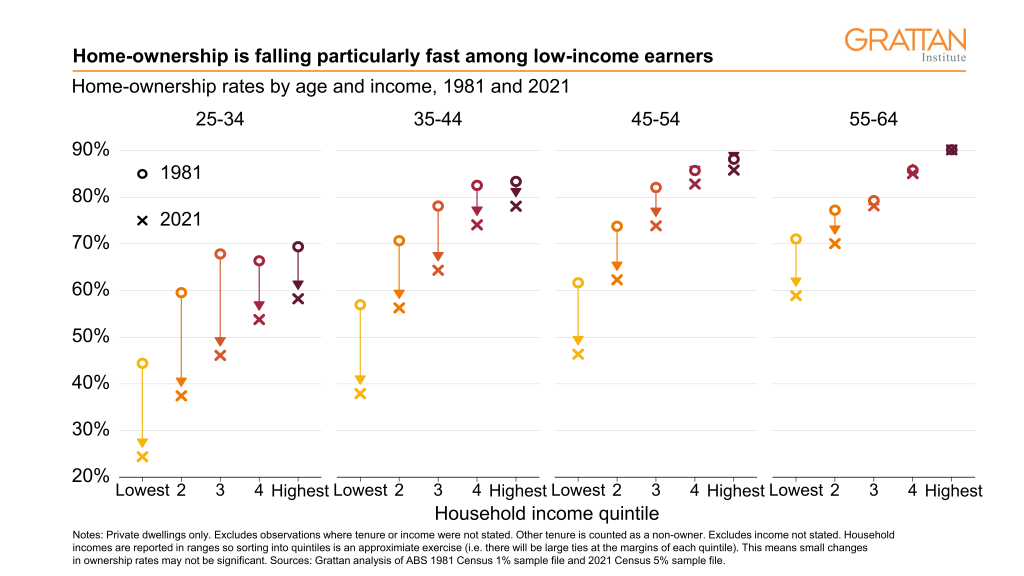

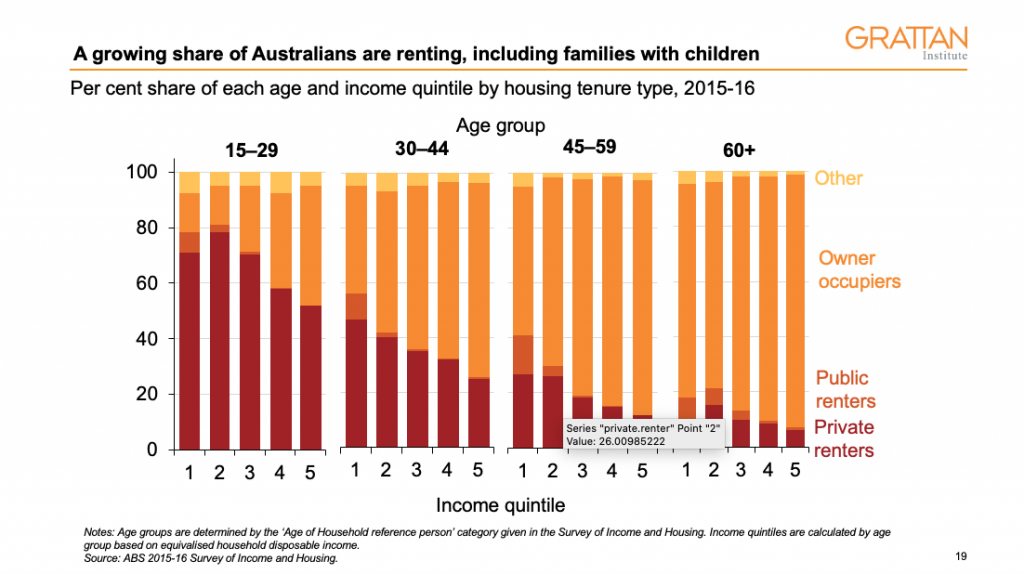

But now home ownership rates are falling fast, especially among the young and poor. Between 1981 and 2021, home ownership rates among 25-34 year-olds fell from more than 62 per cent to 44 per cent, and among the poorest 40 per cent of that age group it has almost halved, from 52 per cent to 32 per cent.

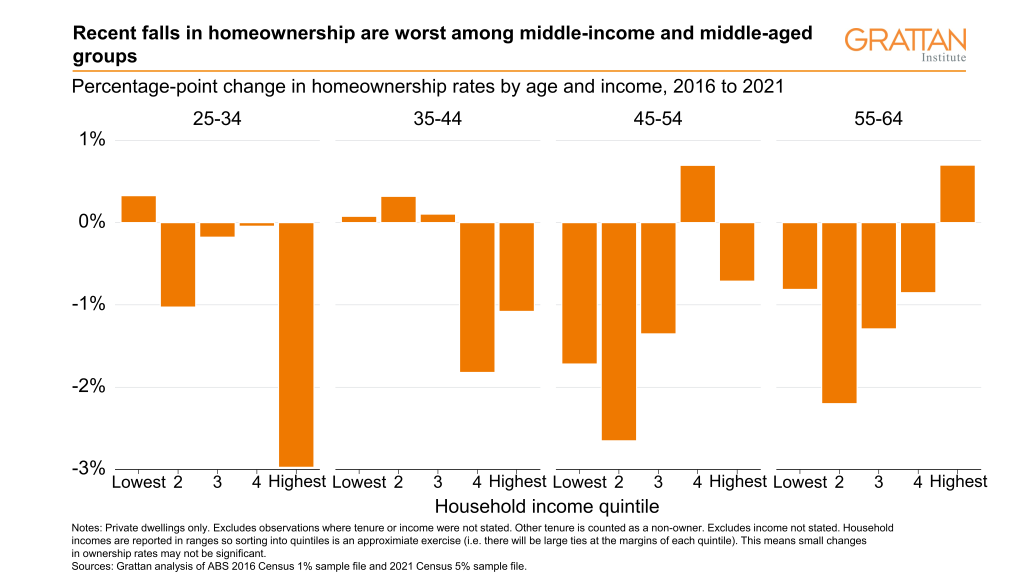

Since the last Census, we’ve started to see accelerating declines among middle-income households too, with noticeable falls in home ownership at all age levels, and including older, middle-income households.

Home ownership is also falling among poorer older Australians. Among the poorest 40 per cent of 45-54 year-olds, just 53 per cent own their homes today, down from 71 per cent four decades ago.

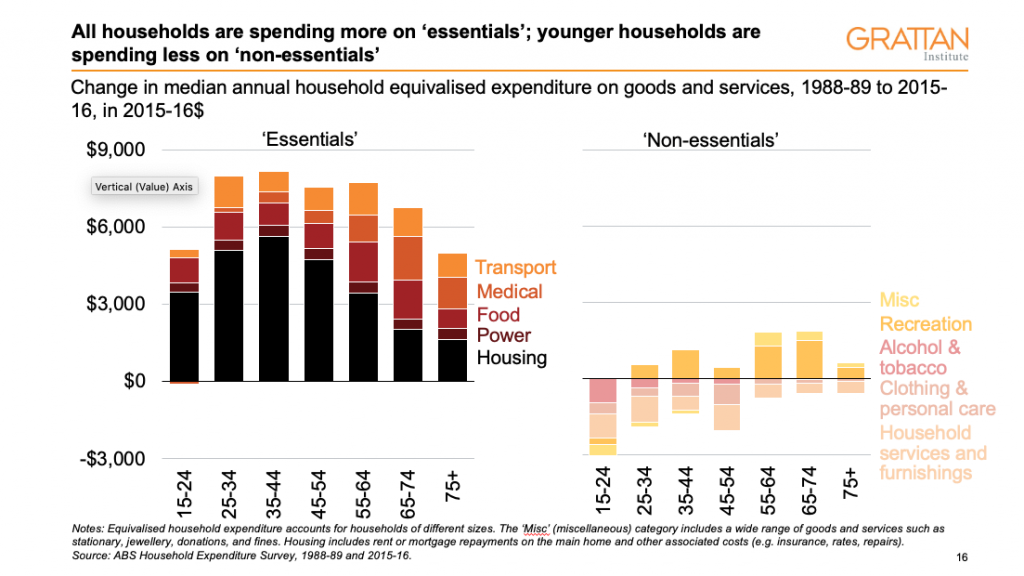

Nor can we blame too many avocado brunches: young people spend less on ‘discretionary’ items – recreation, alcohol and tobacco, clothes and personal care, household services and furnishings – in real terms today than people of the same age three decades ago.

And to the extent that they are spending more it’s on essentials – housing, power, food, medical care, and transport – with rises in housing costs being the biggest contributor.

Instead, home ownership is falling because it takes much longer today to save for a deposit. In the early 1990s it would take the average Australian about seven years to save a 20 per cent deposit for a typical dwelling. Now it takes almost 12 years. Unsurprisingly, a growing share of Australians are relying on the ‘Bank of Mum and Dad’ for a deposit.[27]

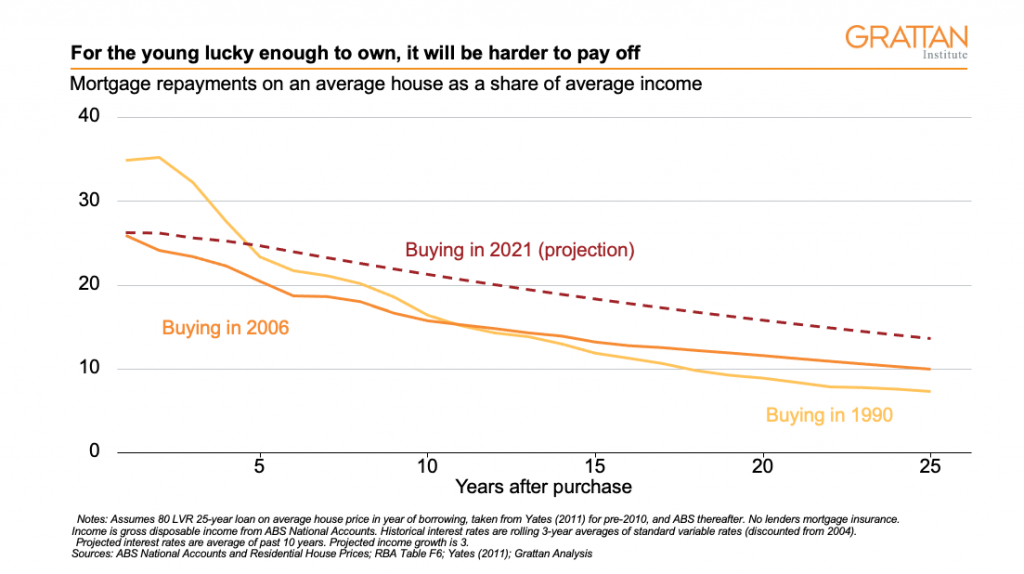

And even for those lucky enough to break into ownership, their houses are likely to be harder to pay off than previous generations. They’ve got big loans at low, but now rising, rates – a fundamentally different prospect than their parents, who took on smaller loans at high rates that quickly went into structural decline.

Meanwhile older renters with a deposit won’t be in the workforce long enough to pay off a home by the time they retire, especially now that interest rates are rising.

Many older Australians were never able to break into the market as prices far outstripped incomes. Others have found it too hard to get back in after losing the home after a separation. Less than half of women who separate from their partner and lose the house manage to purchase another within 10 years.[28]

A threat to a comfortable retirement

Today’s younger renters are tomorrow’s renting retirees.

Australia’s retirement income system has historically assumed that most retirees would own their home outright, and those that didn’t would probably end up in public housing.

The Age Pension has a distinct horizontal inequity between homeowners and renters, with the family home largely protected from the pension assets test. Retirees who have paid off the mortgage are insulated from rising housing costs, a substantial safety net if they exhaust their retirement savings.

The federal government’s 2020 Retirement Income Review showed that most homeowners are on track for a comfortable retirement. Retirees are less likely than working-age Australians to suffer financial stress such as not being able to pay a bill on time, and more likely to be able to afford optional extras such as annual holidays.[29]

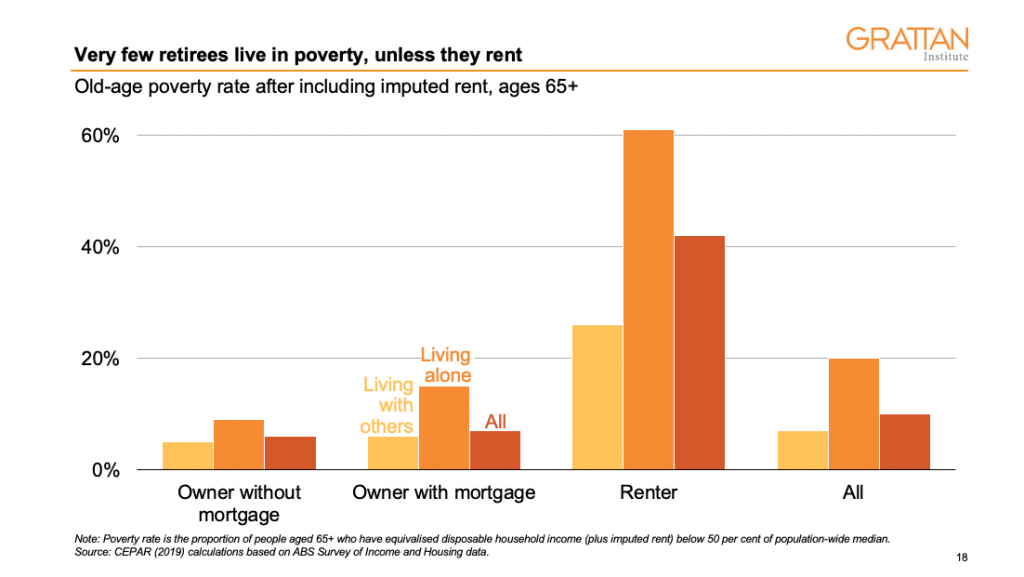

But Australians who rent are facing an increasingly bleak future.[30]

Senior Australians who rent in the private market are much more likely to suffer financial stress than homeowners, or renters in public housing. Nearly half of all retired renters are in poverty – with incomes below half the median. Their numbers will only grow as fewer retirees in future own their homes. Older women are especially vulnerable: women aged over 55 are already the fastest growing group to suffer homelessness in Australia, even if their numbers remain small today.

Home ownership shouldn’t necessarily be the aim for everybody. But older Australians who don’t own their home by the time they retire are often punished by the assets test for the Age Pension, which ignores housing equity but captures other savings in full. And Rent Assistance – paid to pensioners that rent – remains woefully inadequate.

Without change, we risk a generation of older Australians living in poverty in retirement.

A house but not a home

As homeownership falls, more younger Australians are also renting for longer, including while raising families, and in time, in retirement. That puts a premium on stability of tenure.

Being forced to move, or worrying about the possibility of having to move, is a particular problem for families with children in school, for those who are psychologically distressed by the change (often older people), and for poor people who struggle to afford the costs of moving.

Yet renters have little assurance that they can stay in a place as long as they want. Most tenancy agreements are for a fixed term of one year (or less). They often then convert to periodic leases (often referred to as month-by-month leases).

Renters move much more often than owners: two-thirds of private renters had moved in the past two years, compared to one quarter of owners with a mortgage.

Much attention, including in some of Grattan Institute’s past work, has focused on improving the length of tenancies. But the bigger challenge is actually tenancy laws that provide landlords with too-broad a right to terminate leases unilaterally.

Another big part of the problem is that so-called “Mum and Dad” investors also often make terrible landlords.

About 85 per cent of rental properties are owned by landlords who have three or fewer properties.[31] With such small portfolios, landlords prefer shorter leases and relaxed tenancy laws in case the relationship with the tenant turns sour, or they want to sell the property (which often results in the tenant having to leave against their wishes). And as anyone who has rented will attest, trying to get a landlord to complete simple repairs via a property manager can be painful.

Part 5: The Jane Austen world

In contrast to much recent public commentary, income inequality is not particularly high in Australia, and nor is it getting much worse.

But if we consider incomes after accounting for housing costs, inequality is growing, with the poor being hurt the most.

The real (that is, inflation-adjusted) incomes for the lowest 20 per cent of households increased by about 26 per cent between 2003-04 and 2019-20. But their incomes after housing costs increased by only about 12 per cent. Low-income Australians are spending much more than they used to just to keep a roof over their heads.

In contrast, real incomes for the highest 20 per cent of households increased by 47 per cent, and their after-housing incomes by 43 per cent.[32]

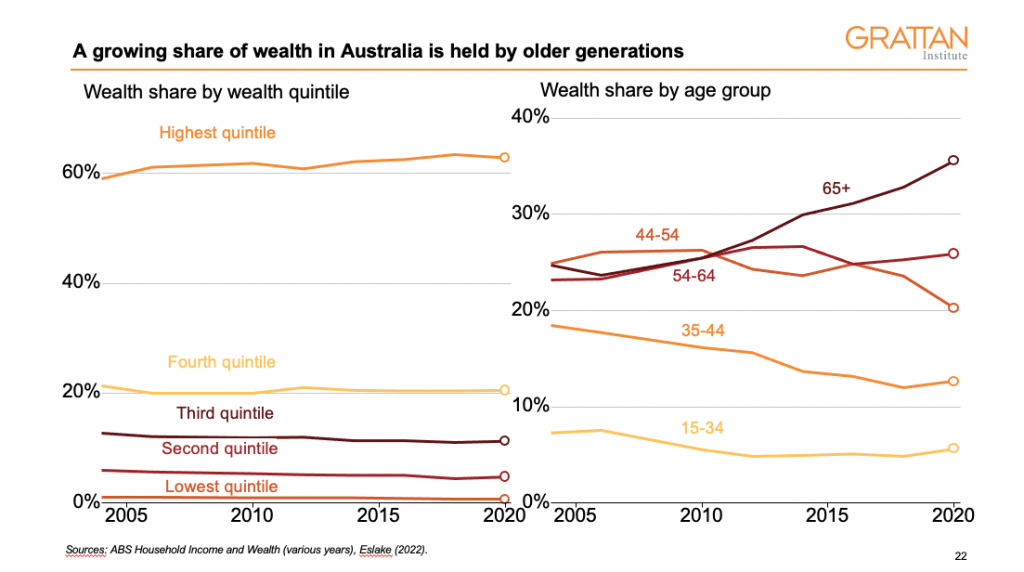

And wealth inequality in Australia, while still below the OECD average, has been growing over the past two decades.

Home ownership in particular is increasingly benefiting the already well-off. Since 2003-04, increasing property values have contributed to the wealth of high-income households by more than 50 per cent. Wealth for low-income households has grown by less than 10 per cent.

In his 2014 book, Capital in the 21st Century, Thomas Piketty argued that growing wealth inequality is the natural tendency of capitalism, interrupted only briefly in the 20th century by two world wars.[33]

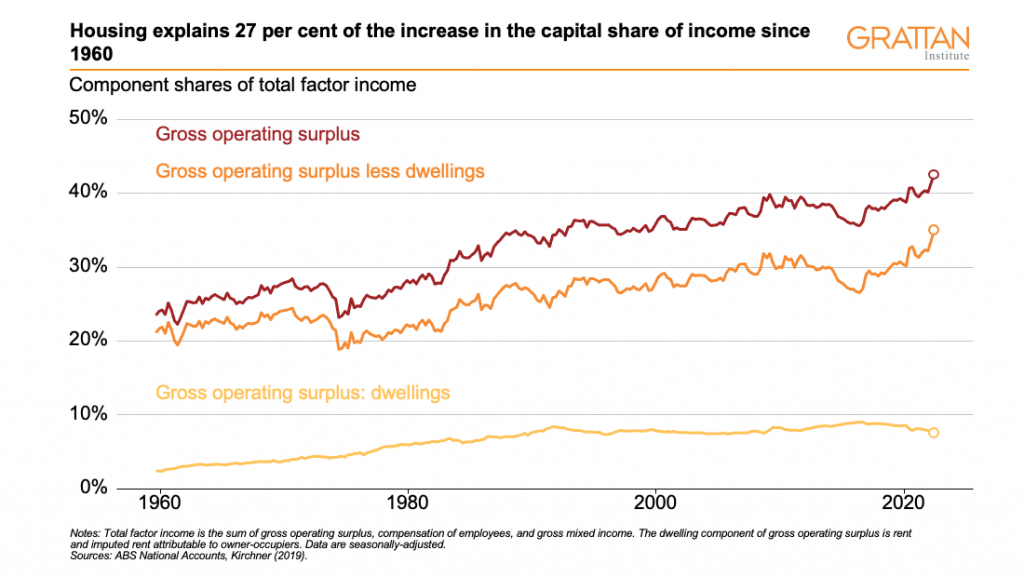

In fact, the rising share of capital income in Australia – a subject of great debate at the recent Jobs and Skills Summit – is at least partly explained by the rising cost of housing and the land upon which it is built.

US economist Matt Rognlie showed that the recent upward trend in the capital share of national income is driven by housing.[34] He argued that relatively scarce housing – a topic we’ll return to shortly – effectively explained all the increase in the capital share of national income in the post-war period, and the corresponding fall in the share of national income going to labour. In short, housing (and land) has become relatively scarcer, and therefore more expensive.

Similar analysis for Australia shows that more and more national income is coming from housing. Rents – actual and imputed – used to make up just 2 per cent of national income in Australia. Now it’s almost 10 per cent. This effect along explains more than a quarter of the rise in the capital share of income since 1960.

Those looking to restore labour’s share of income – such a huge focus at the Jobs Summit – could do worse than look at the cost of housing.

The growing divide between the housing “haves” and “have nots” also risks being entrenched as wealth is passed onto the next generation.

An increasing share of Australian wealth today is in the hands of the baby boomers and older generations. The swelling of our national household wealth to $14.9 trillion[35] – largely concentrated among older groups — means there is an awfully big pot of wealth to be passed on.

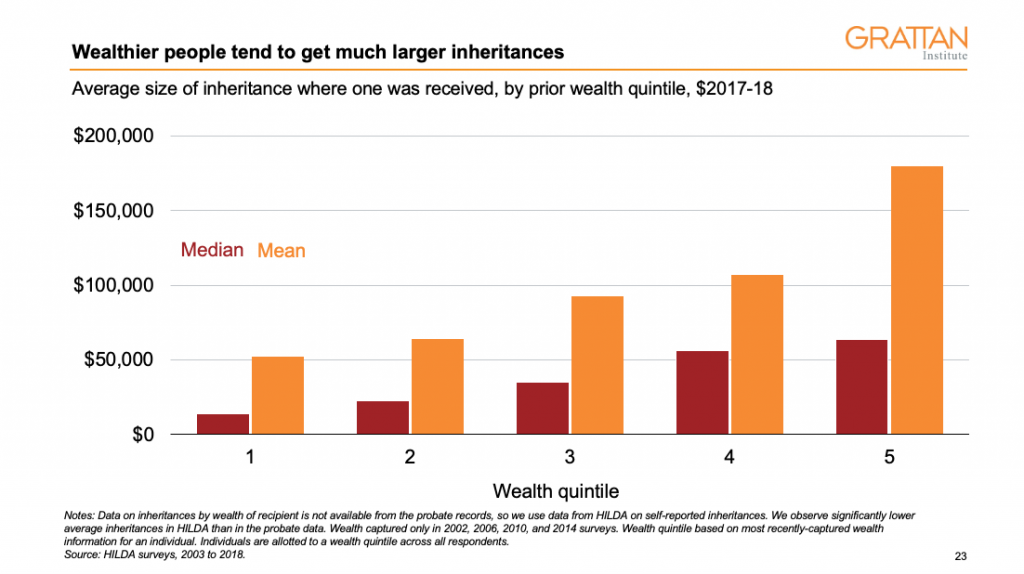

Big inheritances boost the jackpot from the birth lottery. Richer parents tend to have richer children. Among those who received an inheritance over the past decade, the wealthiest 20 per cent received on average three times as much as the poorest 20 per cent.

In fact, one recent study estimates that 10 per cent of all inheritances will account for as much as half the value of bequests from today’s retirees.

And inheritances are increasingly coming later in life. As the miracles of modern medicine have extended life expectancy, the age at which children inherit has increased. The most common age to receive an inheritance is late-50s or early-60s – much later than the money is needed to ease the mid-life squeeze of housing and children.

Large intergenerational wealth transfers can change the shape of society. They mean that a person’s economic position can relate more to who their parents are than their own talent or hard work.

Part 6: How expensive housing stifles economic dynamism

Expensive and scarce housing also has big economic consequences.

Australia is dominated by services industries, where flexibility in where workers and businesses can locate boosts innovation and productivity. Cities tend to be more productive, as is reflected in higher wages, GDP, and rates of innovation per person, particularly towards the centre of big cities.

How much businesses can co-locate is affected by planning rules that guide the availability of land both for businesses and the homes of the people who work in those businesses. Fewer restrictions on land use and subdivision will increase economic growth by enabling more people to access more jobs, while allowing firms to optimise their location.

Recent US studies estimate that GDP would be between 2 and 13 per cent higher if enough housing had been built in cities with strong jobs growth such as New York and San Francisco. These effects would be smaller in Australia because most of us live in one of the five largest cities, but it’s still a huge hit to our living standards.[36] Cities are economic engines, but we’ve constrained access to them. Even people who do get to live close to our cities are less productive than they could be because they can’t combine their skills with people who have been priced out of the city.

Long commutes mean it is harder for both parents to work, with women generally the ones who end up working less. Female workforce participation in outer suburban areas is typically 20 percentage points lower than for men.

Increasingly, important life outcomes – performance in school, employment, even life expectancy – are determined by where people live and the quality of the homes they live in.

And high household indebtedness constrains the capacity of young people to take on the risk of starting a business or even considering a mid-life career change. I suspect we’re only just starting to understand the impact of high household debts on economic dynamism and risk-taking in our economy.

Part 7: We need a national housing plan

What I’ve outlined tonight is a big set of challenges. Rising land values, and the growing gap between those who own land and those that don’t, are already reshaping Australia in profound ways.

These challenge are not insurmountable. Attempts at progress here have made some inroads, and there are lessons from overseas.

The recently-elected Albanese Government has pledged to establish a national housing and homelessness plan. If I could treat this address as a pre-emptive submission, as well as a reform pitch heading into upcoming state elections in Victoria and NSW, I would highlight the following priorities:

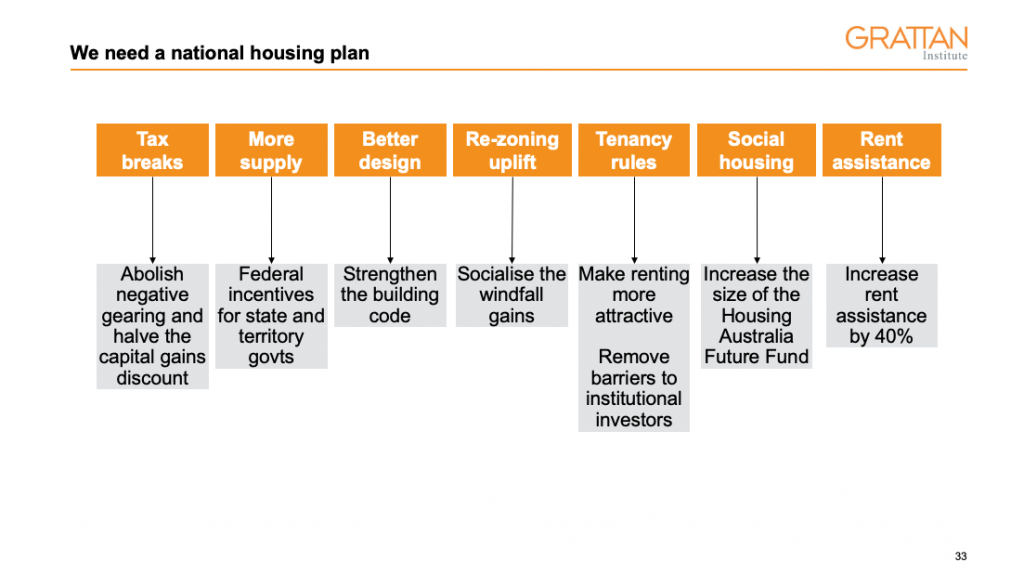

Scale-back housing tax breaks

First, the most obvious way the federal government can materially reduce housing demand is by reducing the capital gains tax discount and abolishing negative gearing. The effect on property prices would be modest – they would be roughly 2 per cent lower than otherwise.

Economic benefits would flow too. The current tax arrangements distort investment decisions and make housing markets more volatile. Reform would boost the budget bottom line by about $5 billion a year. Contrary to urban myth, rents wouldn’t change much, nor would housing markets collapse. Instead, investors would sell investment properties and first homebuyers would buy them. So while the impact of tax reform on house prices would be small, the impact on rates of home ownership would be a lot larger.[37]

Support the states to build more homes

Second, houses would become more affordable if we built more of them.

It’s the states, rather than the federal government, that have constitutional responsibility for land-use planning. The states set the planning framework, and they govern local councils that typically assess development applications.

But the federal government can and should help to boost the supply of housing, especially now that the government has committed to boosting the permanent migrant intake from 160,000 to 195,000 for this year.

Fixing land-use planning is politically hard for state governments because many residents don’t want more housing where they live. The federal government should make it worth the states’ while to do so by paying them for building more housing.

The federal government could set targets for new housing construction, and pay the states for each house built above a baseline. A new federal statutory authority, Housing Australia, could keep score.

There’s plenty of precedent. Under the National Competition Policy, the federal government paid the states nearly $6 billion over 10 years in exchange for much-needed regulatory and competition reform. The Productivity Commission later concluded that the benefits of the policy massively outweighed the costs.[38]

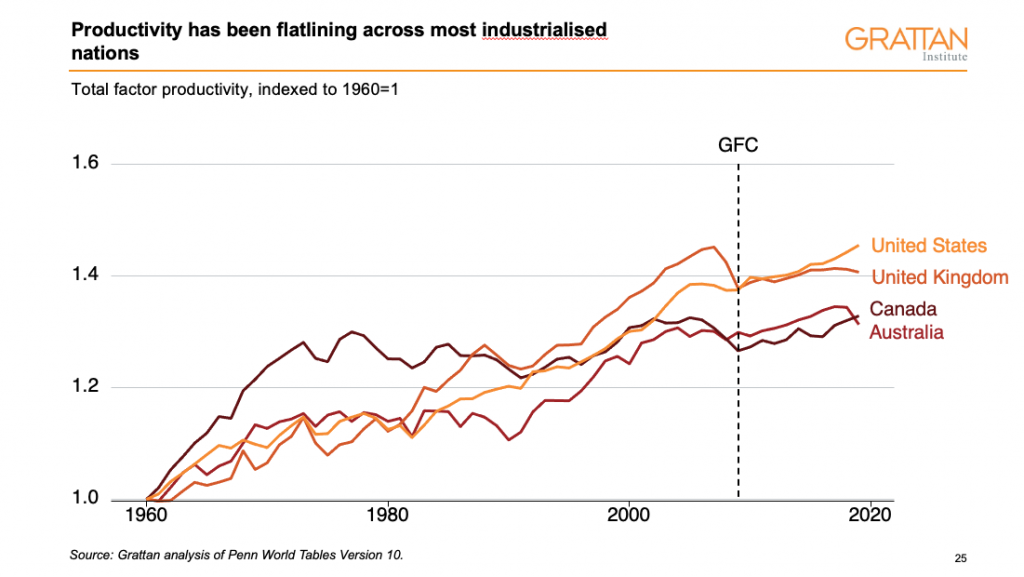

A similar approach today could help solve Australia’s housing affordability crisis and also boost Australia’s lagging productivity growth. Future federal governments would reap a fiscal dividend via the higher tax revenues that would flow from stronger economic growth as we built more homes close to jobs.

A sustained increase in housing supply would have a big impact on house prices in the long term. For example, if an extra 50,000 homes were built each year for the next decade, national house prices and rents could be 10-to-20 per cent lower than they would be otherwise.[39]

In 2016, Auckland – a city of 1.5 million – re-zoned about three-quarters of its suburban area to promote the construction of more dense housing. Researchers found that this led to a doubling of the city’s rate of housing construction.[40] Researchers at Yale University found that in the past five years, New Zealand’s second-largest city had built an extra 26,903 homes – that is, an extra 5 per cent – as a result of the change. If that change occurred across Australia’s major cities, house prices and rents could fall by at least 10 per cent.

And there’s no reason state governments can’t also build more homes directly using state developers to do so, as they used to.

Support better building design rules

Public concern about new housing development isn’t just because of NIMBYism. Anyone who looks around the urban landscape in Melbourne or Sydney can see that the quality of much of what we’re building leaves a lot to be desired.

New developments are one-shot games. Once housing it built, it’s there for decades.

Down the road from our old home in Preston was a large industrial site that was (rightly) zoned for 6-to-8 stories. That density was appropriate for the size of the site and its location close to trains and trams. But the neighbours would feel a lot better about it if that development was well designed and well built.

If local residents can’t be confident that developments will be well designed and well built, it’s perfectly rational for the residents to oppose them.

Which is why at the same time as we relax land-use planning rules, we should strengthen both the building code and design rules governing things like building setbacks.

The Victorian Government is already progressing down this path via the Future Homes Initiative – something Grattan had a hand in designing — having run an architectural competition to canvass high-quality designs for medium-density developments. The next step in the process is to offer developers who use those designs an accelerated pathway through the planning system.

And there is no reason that a state government developer couldn’t also pick up those designs and use them in the construction of new housing.

Push states to establish re-zoning uplift taxes

Local residents often also object to more development because they think developers are getting a free kick. Re-zoning of land generates large unearned windfall gains for landowners. Just think of the bonanzas that have flowed to land-holders from re-zonings in Melbourne’s Fishermans Bend and the Docklands.

Showing that more of the gains from re-zonings are being returned to the community would build the community support for more housing. Which is why any planning reforms at the state level should be paired with greater use of windfall gains taxes on land uplift.

It’s a myth that charges for changes in land use raise home prices. Australian evidence suggests those lucky enough to own land before it is rezoned pay the charges rather than pass them on to eventual homebuyers – which might be why the developers object. And future developers will pay less for their land, because the expectation of windfall gains won’t be built into the price.

The ACT Government has charged 75 per cent for land value uplift for three decades without scaring away developers.

Taxing the uplift from property re-zonings – a form of monopoly rents arising from planning decisions – are one of the most efficient taxes we have.

Fix tenancy laws and encourage institutional investment in housing

States governments should amend tenancy laws to make renting more attractive

Tenancy laws are supposed to ameliorate some of the unequal bargaining power that landlords often have over tenants. But landlords often have the upper hand in negotiations if the tenant needs to get a roof over their head quickly – the consequences of being homeless for a week are much greater than missing out on one week’s rent.

Several states have recently made some progress in this regard, but much more still needs to be done.

Renting could also be improved by removing barriers to institutional investors to invest in market-rent residential housing. Institutional investors are better placed to offer renters security of tenure, since the costs of getting a bad tenant are defrayed across hundreds if not thousands of properties.

And while mum-and-dad landlords are essentially anonymous, prominent institutional landlords would have a brand to protect. For example, AustralianSuper or Cbus could use the economies of scale across thousands of properties to offer a higher-quality service directly – think professional tradies on call 24 hours a day – rather than sit behind traditional property managers.

But currently, land taxes simply make it uneconomic for large investors to own residential property rented at market rates. These taxes are charged at progressive rates, often with generous tax-free thresholds, on the combined value of all properties owned by a landlord.

And state governments also shouldn’t be afraid to build more housing themselves and rent it out at market rents to tenants, as is common overseas.

Build more social housing

Social housing – where rents are typically capped at 25 per cent of tenants’ incomes – can make a big difference to the lives of vulnerable Australians. Australian evidence[41] and international experience[42] shows social housing substantially reduces tenants’ risk of homelessness.

Yet the stock of social housing – currently around 430,000 dwellings – has barely grown in 20 years, while Australia’s population has increased by 33 per cent. About 6 per cent of housing in Australia was social in 1991. It’s now less than 4 per cent.[43]

The Albanese Government’s Housing Australia Future Fund, which will build 30,000 social and affordable housing units over the next five years, is a start. And I’m proud that Grattan Institute played a big role in getting that off the ground with the former Shadow Housing Minister, Jason Clare.

The frustration of past federal governments with state inaction on social housing is not without some basis. The last big federal social housing investment was the $6 billion Social Housing Initiative by the Rudd-Gillard governments, which built 20,000 social homes during the Global Financial Crisis and renovated thousands more. In the decade since, state investment in social housing has been anaemic.

In the five years leading into COVID, the total stock of social housing increased by just 1,600 homes. Only in response to the COVID crisis have state governments adopted social housing construction programs as economic stimulus, notably the ‘big housing build’ in Victoria.

The Federal Government should require state governments to match federal contributions to new social housing, as a condition of any grants being allocated to their state. Any state that does not agree to provide matching contributions would be ineligible for any capital grants for social housing in that year, with the proceeds instead reinvested in the Future Fund and re-distributed across all states the following year.

Raise Rent Assistance

Beyond ensuring a flow of additional social housing for those at greatest risk of long-term homelessness, further support for low-income housing should be focused on direct financial assistance via increases in Commonwealth Rent Assistance.

Commonwealth Rent Assistance should be boosted by at least 40 per cent and it should be indexed to changes in rents typically paid by people receiving income support. This would be a fair way to reduce financial stress and poverty among poorer renters because, unlike social housing, everyone who’s eligible gets access to it.

It’s also well targeted: about 80 per cent of Rent Assistance goes to the poorest fifth of households. Rents wouldn’t increase much, because only some of the extra income would be spent on housing.[44]

The size of the rent assistance program has increased, because the number of people eligible has expanded as home ownership rates among low-income earners have fallen. Total Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA) spending has gone from $1.9 billion in 2003-04 to $5.4 billion in 2020-21. After adjusting for inflation, that is a 93 per cent increase in spending on Rent Assistance, or a compound average growth rate of 3.9 per cent a year over that period.

Given the challenges in getting governments to spend more on poverty alleviation, that’s a big success. Few other spending programs have enjoyed that level of real spending growth. It shows the benefits of a demand-driven program.

Part 8: We have a choice

In Australia’s past, both low- and high-income earners, young and old, owned homes. Homelessness was rare. But over the past 40 years, housing in Australia has transformed.

Today, home-ownership largely depends on income, and how wealthy your parents are. Housing is contributing to widening gaps in wealth between rich and poor, old and young. Lower-income households are spending more of their income on housing and are under more rental stress.

But governments have continued both to promise improved affordability, and to prefer the easy policy options. It is no surprise that trust in government continues to fall.

If governments really want to make a difference, they need to explain the hard choices, to prepare the ground for the tough decisions that need to be made.

Either people accept greater density in their suburb, or their children will not be able to buy a home, and seniors will not be able to downsize in the suburb where they live. Economic growth will be constrained. And Australia will become a less equal society – both economically and socially.

This is a problem we can fix, but only if we make the right choices.

Note: The charts ‘Homeownership is falling particular fast for low-income earners’ and ‘Recent falls in homeownership are worst among middle-income and middle-aged groups’, as well as relevant numbers in the surrounding text, have been updated since we published this lecture. After further investigation, we could not be certain that the income quintiles calculation methodology in the paper from which the 1981 numbers stem matched that employed by the ABS for 2021. The updated numbers are calculated by Grattan using a consistent methodology of unequivalised age-group quintiles using Census sample file basic microdata for each year.

Footnotes

- Hubacek, K. & van den Bergh, J. (2006) Changing concepts of ‘land’ in economic theory: From single to multi-disciplinary approaches, Ecological Economics, Vol. 56, pp. 5-27.

- Solow, R. M. (1956) A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 70, No. 1, pp. 65-94.

- Kelly, J-F., Donegan, P., Chisholm, C., Oberklaid, M. (2014), Mapping Australia’s Economy: Cities as engines of prosperity, Grattan Institute.

- ABS (2022), Australian National Accounts: Finance and Wealth, Table 35: Household Balance Sheet.

- Grattan analysis of ABS Survey of Income and Housing 2019-20

- Jordà, Ò., Knoll, K., Kuvshinov, D., Schularick, M., and Taylor, A. M. 2019. The rate of return on everything, 1870–2015. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. Vol. 134, No. 3, 1225–98.

- Adapted from Wood, D. (2021), John Button Oration: The Next Generation’s Australia.

- Ryan-Collins, J. and Murray, C. (2020), When homes earn more than jobs: the rentierization of the Australian housing market, Housing Studies.

- Tulip, P. and Saunders, T. (2019), A Model of the Australian Housing Market. Reserve Bank of Australia Discussion Paper.

- Tulip, P. and Saunders, T. (2019), A Model of the Australian Housing Market. Reserve Bank of Australia Discussion Paper.

- Eslake, S. (2013), 50 Years of Housing Failure, 122nd Annual Henry George Commemorative Dinner.

- Glaeser, E. (2013), A Nation of Gamblers: Real Estate Speculation and American History. Harvard Kennedy School Policy Brief.

- Coates, B. and Moloney, J. (2022), The National Housing and Homelessness Agreement needs urgent repair, Grattan Institute, p. 4.

- Daley, J. and Coates, B. (2018), Housing Affordability: Reimaging the Australian Dream, Grattan Institute, pp. 45-48.

- A big part of the story is how the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) determines whether a dwelling is occupied. In short, it does its best by using a variety of methods, but, for most dwellings, occupancy “is determined by the returned Census form”. If a form was not returned, and the ABS had no further information, the dwelling was often deemed to be unoccupied. See: Baker, E., Beer, A.,Blake, M., (2022), Look where Australia’s ‘1 million empty homes’ are and why they’re vacant – they’re not a simple solution to housing need, The Conversation.

- Razaghi, T., Landlords hold upper hand, renters set for tough conditions over next 12 months, Domain.

- SQM Research, Weekly Rents.

- Domain, June 2022 Rental Report.

- Ellis, L. (2022), Housing in the Endemic Phase, Keynote Speech to the UDIA 2022 National Congress.

- Jenner and Tulip (2020) estimate that home buyers will pay an average of $873,000 for a new apartment in Sydney though it only costs $519,000 to supply, a gap of $355,000 (68 per cent of costs). There are smaller gaps of $97,000 (20 per cent of costs) in Melbourne and $10,000 (2 per cent of costs) in Brisbane. See: Jenner, K. and Tulip, P., (2020), The Apartment Shortage. Reserve Bank of Australia Discussion Paper.

- For example, see. Murray, C. (2020), Marginal and average prices of land lots should not be equal: A critique of Glaeser and Gyourko’s method for identifying residential price effects of town planning regulations, EPA: Economy and Space. A good discussion of the debate can be found at: Caplan, B. (2022), The Zoning Tax: A Mere Illusion?.

- Daley, J. and Coates, B. (2018), Housing Affordability: Reimaging the Australian Dream, Grattan Institute, pp. 26-27.

- Unfortunately, the fact that Australians are overwhelmingly concentrated in just five cities means we can’t easily conduct similar comparisons for Australian cities since a restriction on housing at one location will increase demand and hence prices for housing at other locations in the same city. So variations in relative prices across the city will substantially understate the total effect of variations in restrictions.

- Gyourko, J. and Molloy, R. (2015), Chapter 19 – Regulation and Housing Supply, Handbook of Regional an Urban Economics, Vol. 5.

- Fitzgerald, K., (2022), Staged Releases: Peering Behind the Land Supply Curtain. Prosper. Murray, C., (2021), A housing supply absorption rate equation.

- Coates, B. (2020), Homelessness is a growing problem, Presentation to the Inquiry into Homelessness in Victoria.

- Coates, B. (2022), Levelling the playing field: it’s time for a national shared equity scheme, Grattan Institute.

- Coates, B. (2022), Levelling the playing field: it’s time for a national shared equity scheme, Grattan Institute.

- Callaghan, M. et. al. (2020). Retirement Income Review, Treasury.

- Daley, J. and Coates, B. (2018). Money in retirement: more than enough, Grattan Institute.

- Daley, J. and Coates, B. (2018), Housing Affordability: Reimaging the Australian Dream, Grattan Institute, pp. 77.

- ABS 2019-20 Survey of Income and Housing Basic Confidentialised Unit Record File.

- Piketty, T. (2014), Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Rognlie, M. (2014), A Note on Piketty and the Diminishing Returns to Capital. 2014.

- ABS (2022), Australian National Accounts: Finance and Wealth, Table 35: Household Balance Sheet.

- Hsieh, C-T. and Moretti, E. (2019), Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 11, No. 2.

- Daley, J. and Wood, D. (206), Hot property: negative gearing and capital gains tax. Grattan Institute.

- Productivity Commission (2005), Review of National Competition Policy Reforms.

- Daley, J. and Coates, B. (2018), Housing Affordability: Reimaging the Australian Dream, Grattan Institute, p. 111.

- Greenaway-McGrevy, R. and Phillips, P., The Impact of Upzoning on Housing Construction in Auckland, 2021.

- Scutella, R. (2018), Social housing protects against homelessness, The Conversation.

- Mares, P. (2018), “You don’t see people sleeping on the streets” – Finland’s Housing First strategy has all but eradicated homelessness. Could the same approach work in Australia?, Inside Story.

- Coates, B. (2021), A place to call home: it’s time for a Social Housing Future Fund, Grattan Institute.

- Daley, J. and Coates, B. (2018). Money in retirement: more than enough, Grattan Institute.

Brendan Coates

While you’re here…

Grattan Institute is an independent not-for-profit think tank. We don’t take money from political parties or vested interests. Yet we believe in free access to information. All our research is available online, so that more people can benefit from our work.

Which is why we rely on donations from readers like you, so that we can continue our nation-changing research without fear or favour. Your support enables Grattan to improve the lives of all Australians.

Donate now.

Danielle Wood – CEO