Published at The Conversation, Wednesday 21 November

The most magical time of the year is upon Victorians: election season. The (taxpayer-funded) gifts promised by the major parties far exceed anything Santa could bring. And the multi-billion-dollar toys on everybody’s wish list? Trains, tracks and roads.

There’s nothing unusual about politicians promising big-ticket items to curry favour with voters, but this election the size of these commitments is astronomical: more than A$170 billion worth of projects are on the table.

Grattan Institute has crunched the numbers, investigating the major parties’ transport infrastructure pledges worth more than A$50 million. Although cost is a cause for concern, the recent trend towards first conducting business cases is encouraging.

How did we get here?

Population growth has been a big topic in the lead-up to Saturday’s state election. Politicians often cite it as the cause of ever-worsening congestion, despite evidence that Australia’s cities are actually coping quite well.

It’s often assumed that a city’s transport infrastructure needs to grow at the same rate as population. This misconception allows politicians to promise popular mega-projects in the name of busting congestion.

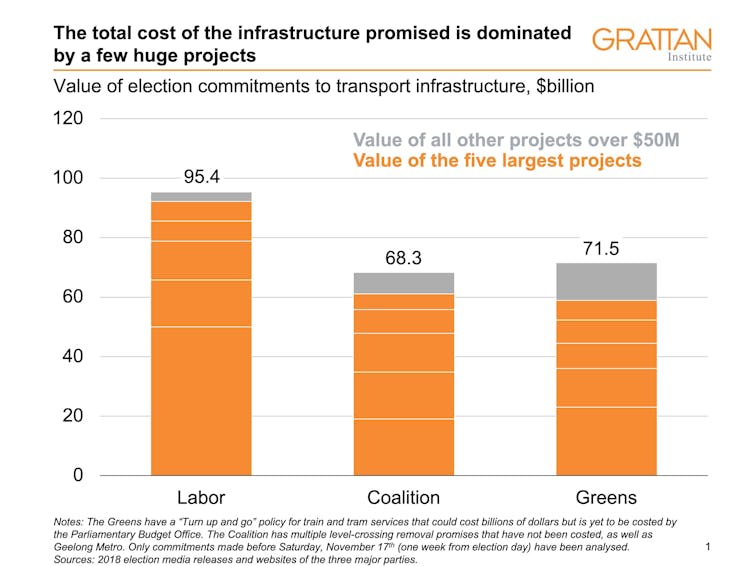

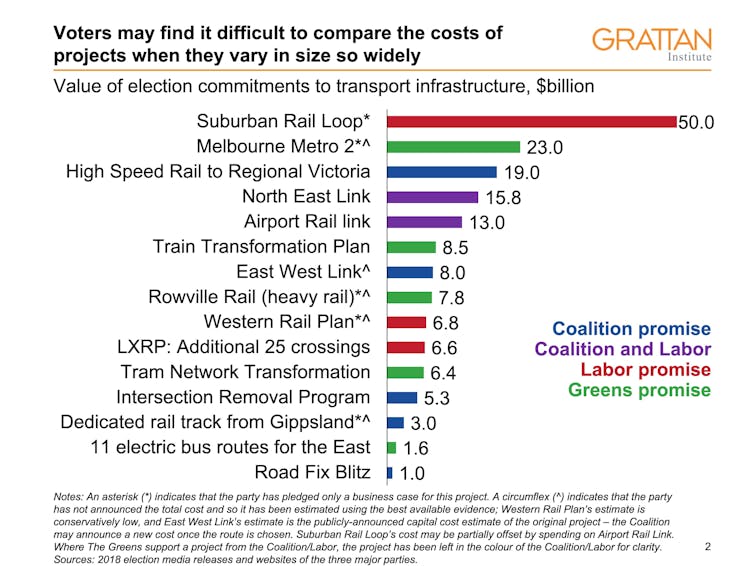

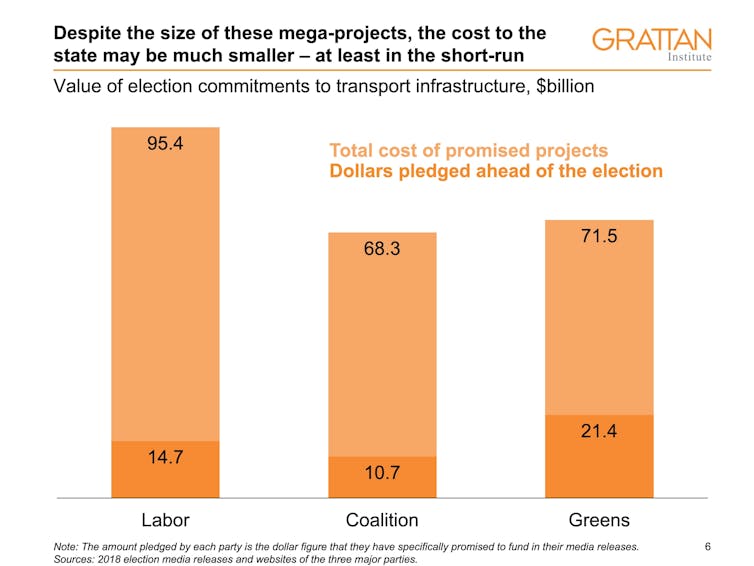

Labor has the most extensive and expensive suite of projects, at a cost totalling A$95 billion. More than half of that is just one project: a A$50 billion suburban rail loop that rings around Melbourne’s middle suburbs and connects most train lines.

The Coalition’s commitments total $65 billion. The difference in the major party totals is mainly due to the smaller scale of the Coalition’s flagship rail project: a A$19 billion promise to deliver “European-style high-speed rail” to Victoria’s regional cities and towns.

These promises mean that every party wants the credit, if elected, for being the government that built the largest transport infrastructure project in our nation’s history. The current title holder, WestConnex in Sydney, totals only A$16.8 billion.The Greens have so far committed to projects worth at least A$72 billion. The largest is Melbourne Metro 2 at an estimated A$23 billion.

Critics might point out that Labor and The Greens have committed only to business cases for the suburban rail loop and Melbourne Metro 2 respectively. But since two-thirds of infrastructure projects announced with a price tag end up being built, voters are right to treat these promises as commitments to the entire project. Unfortunately, there is no election material with the nuanced message: “We support a business case for this project, which we will have rigorously assessed by an independent body, and if the project’s costs outweigh the benefits, we’ll scrap it.”

No matter who wins on Saturday, the full cost of the promised infrastructure won’t be felt immediately. Many of these projects are slated to run over years or decades and will have an impact on several budgets. Voters have the job of deciding not just where they want their money spent, but their children’s money too.

Total spend isn’t the only difference

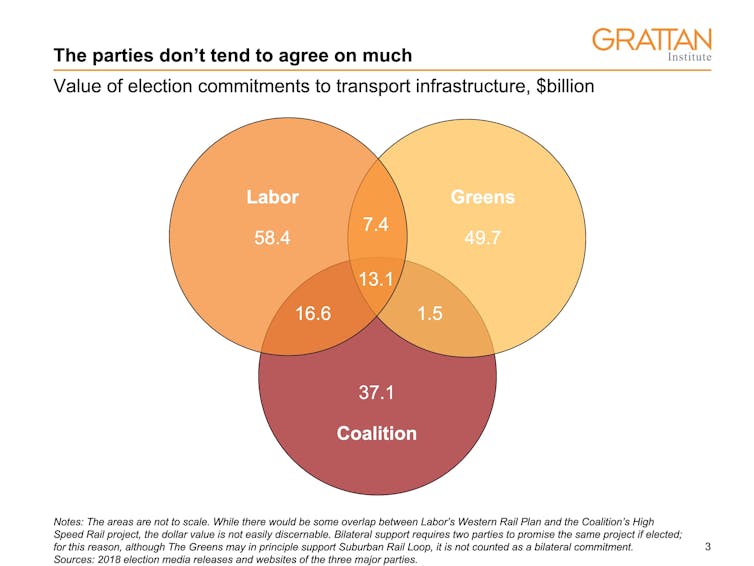

The major parties don’t tend to agree on much, especially around election time. The value of their unilateral pledges exceeds the value of projects with multi-party support.

The largest promised project to have clear support from all three parties is the airport rail link, estimated at A$13 billion. (The Greens support this project but will not be announcing it as a policy until the business case is complete.)

Parties differ in both what they promise and where they want to build it, and the patterns are fairly predictable.

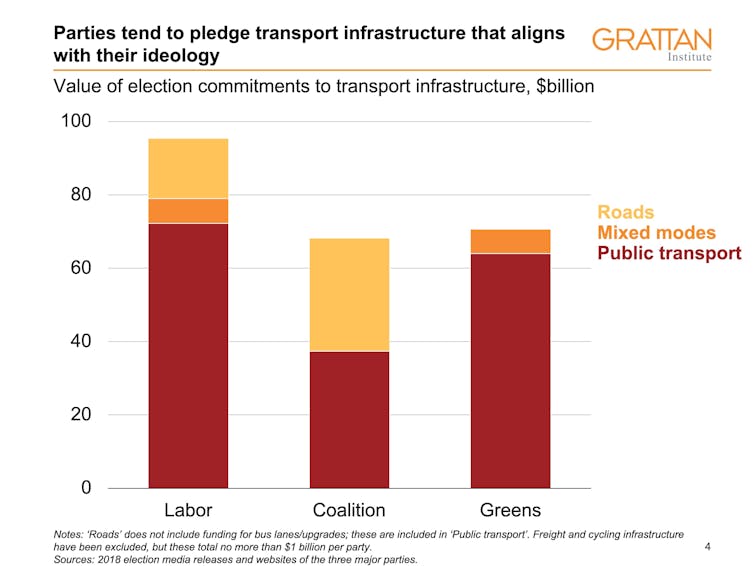

Public transport (particularly heavy rail) is the winner this election, but it’s clear that parties tend to choose projects that fit with their ideology. The Coalition has promised the most for roads. The Greens have focused almost exclusively on public transport.

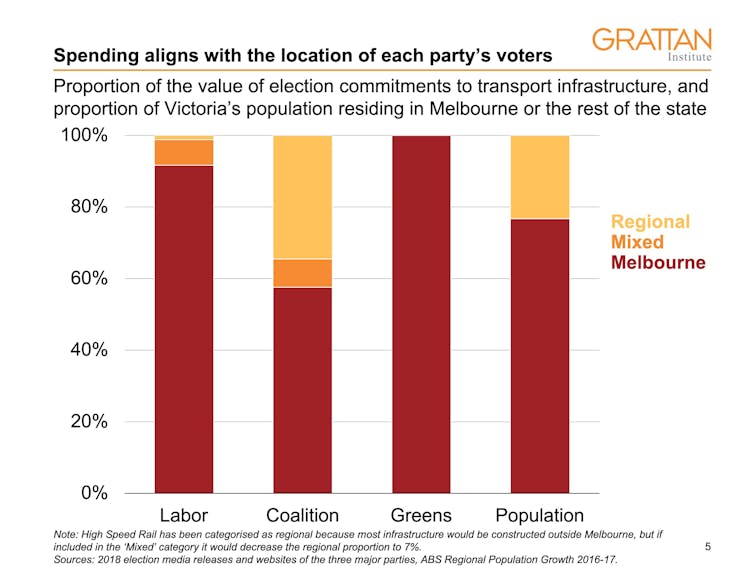

The Coalition’s projects are skewed towards benefiting regional Victorians. Labor and the Greens have announced projects that focus mainly on Melbourne.

These patterns may be influenced by where the parties’ respective voting bases tend to cluster, but also by the demands of different parts of the state. For instance, congestion may be a less salient issue in the regions, so voters there may prefer health or education investment rather than big-ticket transport infrastructure.

Is all this spending wise?

There is often a mismatch between the total cost of a project and how much a party pledges in an election campaign. The discrepancy is due to three factors:

- only a business case is promised

- the state government is expected to bear only part of the cost

- the party has not made the funding arrangement clear.

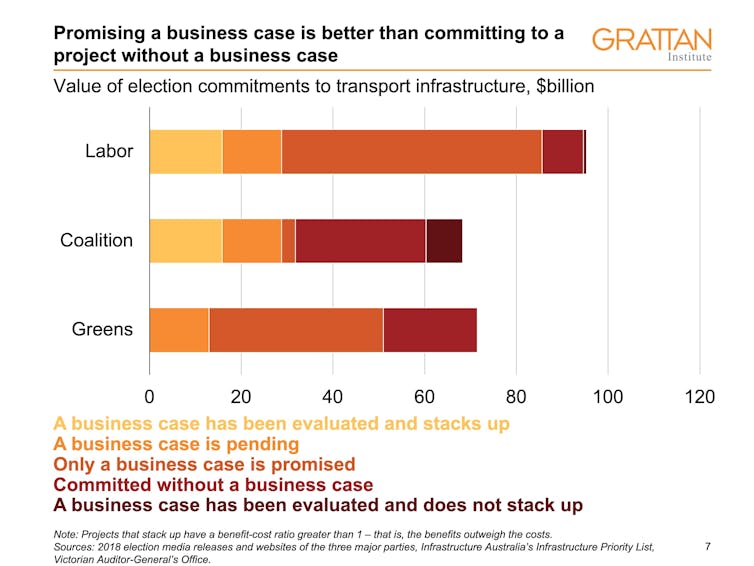

An interesting phenomenon this election is the practice of pledging a business case only. At first glance, this appears misleading – voters might be enticed by the prospect of a mega-project, yet the party has to fork out only about 1% of the total cost if it wins.

Ideally, parties would have independently evaluated business cases ready before committing to projects, so voters could rest assured that any promised project is a smart one. This is important because projects announced prematurely tend to have the largest cost overruns. And without doing due diligence, there’s not enough evidence that the initiative will deliver enough benefits to justify its price; voters won’t know whether it’s a good use of taxpayer funds until it’s built and they’re stuck with it.

So promising a business case is still better than committing to a project without one – or, worse still, committing to a project that clearly does not stack up.

Both Labor and the Coalition are guilty here. Labor has committed to rail duplication between Waurn Ponds and South Geelong, despite Infrastructure Australia – the nation’s independent advisory body – warning that “the costs of the project outweigh its benefits”. And the Coalition has promised to revive the massive East West Link, despite the Victorian Auditor-General’s criticism of the original project: “… the EWL business case did not provide a sound basis for the government’s decision to commit to the investment”.

Of the infrastructure promised this election, only the North East Link has a business case that Infrastructure Australia has assessed and approved.

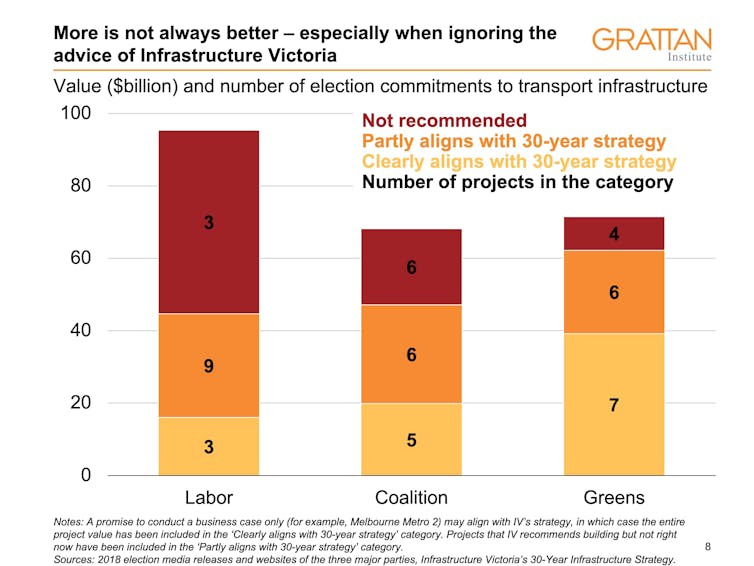

But this is a state election and Infrastructure Australia is required to assess only projects of national significance for which more than A$100 million in federal funding is sought. Fortunately, since 2015 Victoria has had its own independent advisory body: Infrastructure Victoria. It set out recommendations for the state in its 30-Year Infrastructure Strategy.

The Greens’ platform is most closely tied to these recommendations, both by number of projects and total size. While the Coalition has made the most pledges that do not align with Infrastructure Victoria’s strategy, Labor’s set of non-aligned projects is worth far more, owing mostly to the suburban rail loop.

The huge infrastructure promises this election may excite some voters, but for parties to pledge “visionary” projects outside of what Infrastructure Victoria has recommended smacks of hubris. By building their own glitzy mega-projects without doing due diligence, politicians risk choosing badly and failing to solve the underlying problems voters care about. Worse, the state has a finite budget, so worthwhile projects will have to be relegated to the bottom drawer to make way for the attention-grabbing goliaths.

Going into the polls, Victorians should have one thing on their transport infrastructure wish lists: projects with rigorous and independently assessed business cases. Anything less than that is like buying your kids shoddily manufactured, untested toys. And that may well end in tears once they’re unwrapped.

A note on sources and assumptions: Election commitments were sourced from official party media releases and websites. Only infrastructure promises worth more than A$50 million were considered. Given Labor is in government, only Labor promises pertaining to a “re-elected Andrews government” were included. Judgment had to be exercised to avoid double counting when existing promises were subsumed into later ones. Similarly, care was taken not to double-count projects announced as part of a larger program, such as individual level-crossing removals. Where a party released a range of cost estimates, the largest value was taken.

![]()