Published at The Conversation, Wednesday 11 March

The narrative for the upcoming budget appears to be in a state of flux. Is it still to be “tough love” or “we’re from the government and here to help you”?

The framers of the health spending narrative face the same quandary. For the last 15 months all we have heard is the “health system is unsustainable” discourse. However, last week’s Intergenerational Report delivered a confusing prediction: Commonwealth health expenditure will decline over the next two decades.

Previous Grattan Institute work has shown health to be the fastest-growing area of government spending. And the reason for the shift in the 2015 Intergenerational Report is not changed assumptions, since the 2015 ones are very similar to those in previous reports. So, how can this be?

The Intergenerational Report looks at the Commonwealth government’s finances, not the whole of the public sector: federal, state and local. It therefore presents only half the picture and may leave Australians with a warped view of government finances.

Projected health expenditure

The Intergenerational Report is organised around three spending projections: two based on whether the 2014 budget measures are implemented and another, labelled “previous policy”.

Both the report’s “proposed policy” scenario and its “currently legislated” one show a remarkably different outlook for government health spending from previous intergenerational reports.

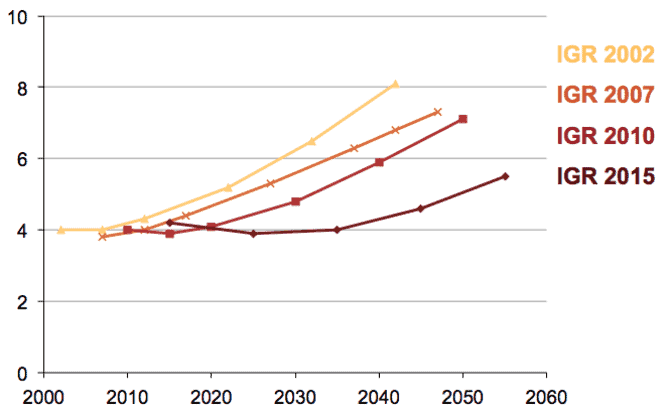

Intergenerational report projections of Commonwealth government health expenditure as share of gross domestic product. 2015 Intergenerational Report/Grattan Institute

Following a decline in Commonwealth health expenditure over the next couple of decades, the report projects health will account for a much lower proportion of GDP than previously reported.

Budget impact on the states

The 2015 Intergenerational Report adopts the same mixed focus as the previous three: it looks both on the economy broadly and the Commonwealth budget specifically. It captures the big picture about ageing, productivity growth, GDP and so on.

Yet when it comes to budget impacts, it is truly myopic. It describes the impact on the Commonwealth budget with great clarity but its description of the impact on the budgets of the states and territories is so out of focus as to be non-existent.

This doesn’t matter for those areas of government expenditure that are solely the preserve of the Commonwealth, but it has a significant impact in areas of policy where responsibility is shared and there are significant intergovernmental transfers.

In 2014-15, the Commonwealth is budgeted to transfer A$46.3 billion to the states as specific purpose payments. Health grants will account for more than a third of the transfers (A$16.4 billion).

The 2014-15 budget took an axe to Commonwealth payments to the states for health care. It abruptly terminated grants to states under the ironically named National Partnership Agreements, and, from 2017, sliced more than $1 billion a year from public hospital grants through reduced indexation.

Because changes to state grants don’t require Senate approval, these cuts are incorporated in both the Report’s “currently legislated” scenario as well as in “proposed policy’.

The effect is that the Commonwealth appears to have its health outlays more or less under control. The problem for the states, however, is dire.

Rising health costs

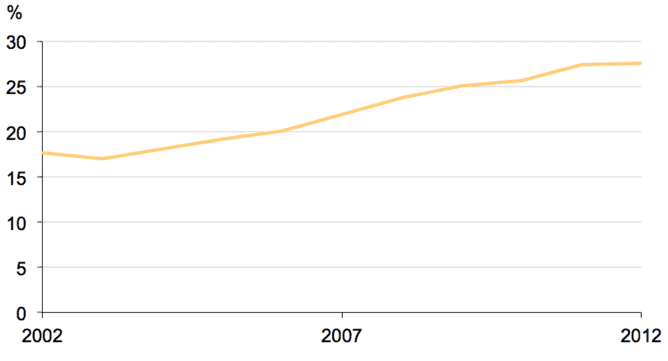

Health spending as a share of state taxation revenue has already increased from about 18% in 2002 to 28% in 2012.

Health share of tax revenue. AIHW/Grattan Institute

The Premier of New South Wales, Mike Baird highlighted the health Commonwealth funding shift in a recent interview:

The biggest challenge facing this state and the nation is health funding. And what happened last federal budget is not sustainable. That was, the commonwealth and the federal government said “we are going to allocate a large part of the future growth in health costs from ourselves to the state governments”.

…The states do not have the capacity to meet those health costs on their own.

The states have been sharing more and more of the hospital cost burden. In 2000-2001 the state share of public hospital costs was 51%. By 2012-13 it had risen to 59%.

Projections of health spending growth in 2008 predicted that state spending would double, in real terms, between 2012-13 and 2032-33.

It was obvious this was not sustainable. A new National Health Reform Agreement was negotiated and signed by the Commonwealth and all states and territories. A specific objective of the agreement was to:

ensure the sustainability of funding for public hospitals by increasing the Commonwealth’s share of public hospital funding through an increased contribution to the costs of growth

That agreement was ripped up in the 2014 budget.

Slashing more than A$1 billion a year from state hospital revenues, as the 2014 Commonwealth budget did, will exacerbate the pressures state governments already face. The Commonwealth has simply improved its position by hurting that of the states. Shifting a problem does not solve it.

The 2015 Intergenerational Report, like its predecessors, gives only half the picture of health-care spending. If these reports are to continue, they must take a broader, national perspective, not merely the Commonwealth’s own interest.

![]()