I’m delighted to be here on the traditional lands of the Wangal and Gadigal peoples, and I’d like to thank David Borger and the Housing Now! Team for the opportunity to speak at today’s Summit.

The housing crisis is real

There are few things as important to people’s lives than having access to safe, secure and affordable housing.

But the people of NSW are not as well housed as they could be – nor, in some ways, are as well housed as they once were.

Housing in NSW, and especially in Sydney, is increasingly expensive. Too many people can’t find a home close to where they want to live and work. And fewer now have a home to call their own.

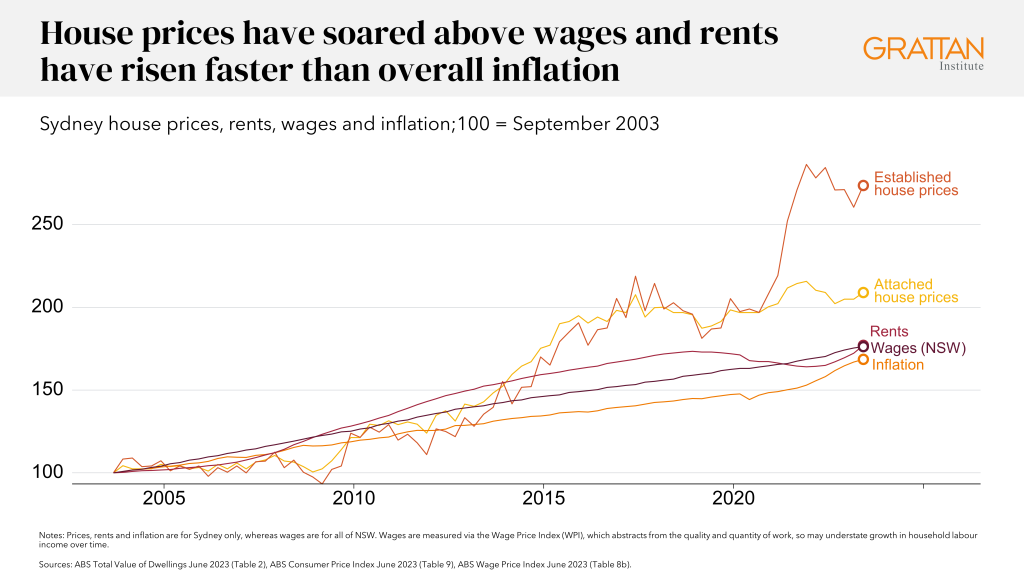

In 2000, the median dwelling in Greater Sydney sold for around six-and-a-half times a mid-career teacher’s salary. By 2022 that same home cost 14 times that salary.

In regional NSW, too, house prices have risen faster than wages.

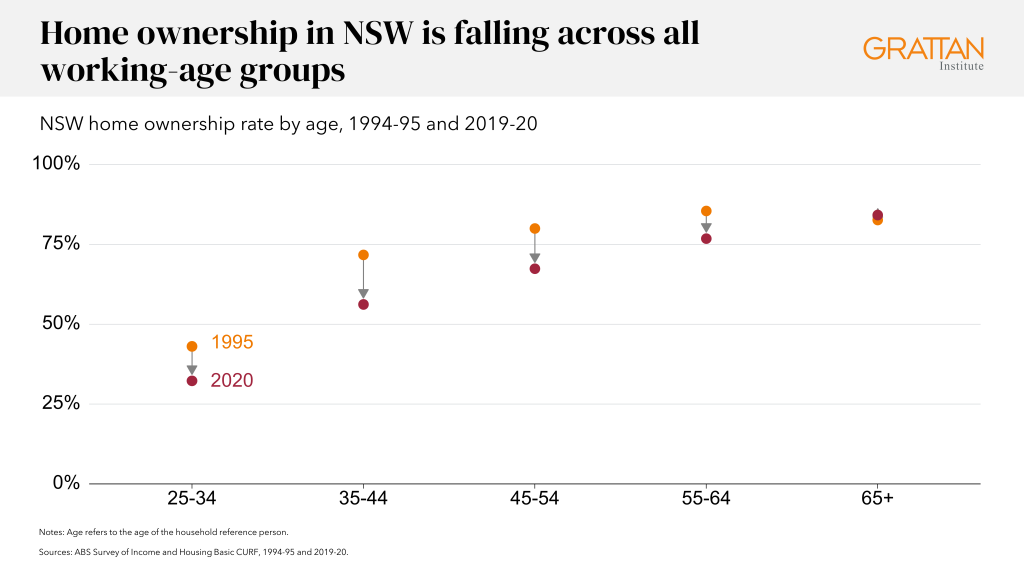

It’s no surprise, then, that fewer working age NSW residents now own the house they live in compared to the 1990s. Home ownership has declined particularly fast among the young, and among the lowest income earners.

In fact unaffordable housing is the biggest threat to a comfortable retirement: half of retirees who rent are in poverty today.

Low-income renters in NSW are doing it especially tough – more than half spent more than 30 per cent of their income on housing in 2019-20 – that’s a higher share than in any other state or territory.

And many NSW residents struggle to find a home at all: around 35,000 were reported as being homeless on Census night in 2021.

The pandemic and its aftermath made our housing problem worse, not better.

Rental vacancy rates are at record lows and asking rents have risen rapidly. After a brief dip, Sydney house prices are once again on the rise, and many observers now expect them to keep rising.

For many people living in this state, the Great Australian Dream is quickly becoming a nightmare.

We haven’t built enough homes

But how did housing become so expensive in NSW – and especially in Sydney?

This is a problem with many causes. Falling interest rates and strong migration over recent decades have both played a role; so has a lack of new social housing, and tax settings that disproportionately encourage investment in rental properties.

But at the heart of the problem is the fact we just haven’t built enough homes to meet the needs of a growing population, especially homes in places where people most want to live – that is, in established suburbs close to jobs, transport, schools, and other amenities.

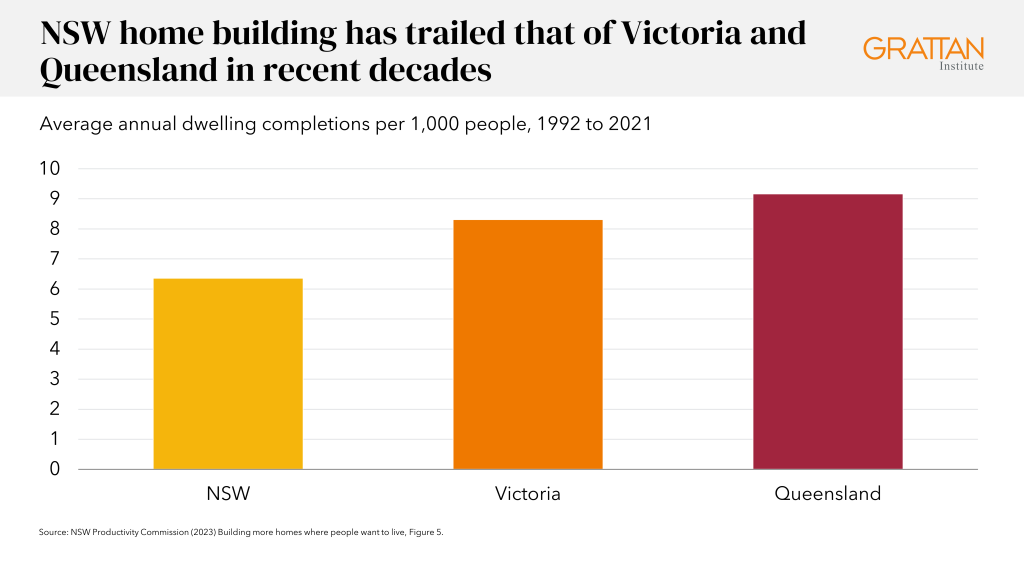

The NSW Productivity Commission recently showed that the state has built just over six new dwellings on average each year per 1,000 residents since 1992, far fewer than in Victoria (eight) and Queensland (nine).

And NSW is building fewer new homes than it once did. In the two decades to 2004, NSW saw an average of 6.9 dwellings completed each year per 1,000 head of population. From 2005 to the present, this has slipped to just 5.8 homes.

This is largely a failure of housing policy, not housing markets.

Land-use planning rules in NSW are highly complex and prescriptive, and particularly restrict many medium- and high-density developments in established suburbs.

Reserve Bank researchers estimated that restrictive land-use planning rules add up to 40 per cent to the price of houses in Sydney, up sharply from 15 years ago. More recent research from the NSW Productivity Commission suggest that planning rules have added over 50 per cent to the cost of a new apartment in Sydney.

The planning system also tends to favour existing residents who oppose change due to concerns about extra traffic congestion, parking, and damage to neighbourhood character. But those people who would live in new housing – if it were to be built – do not get a say.

The specific barriers to building more homes vary across Sydney but the outcome is the same everywhere: the prices of new homes, especially apartments, exceed the cost of building more of them, so fewer homes are being built where people most want to live and work.

More abundant housing would be more affordable

It’s almost so obvious as to go without saying, but housing is NSW would be more affordable if we simply built more of it.

The NSW Productivity Commission estimates that a 10 per cent increase in housing supply – that is, over and above the level needed to match population growth – would lower housing costs by 25 per cent.

This isn’t merely theory.

In 2016, Auckland – a city of 1.5 million – rezoned about three quarters of its suburban area to promote more dense housing. Researchers later found that the policy had boosted the housing stock by up to 4 per cent.

Unsurprisingly, rents in Auckland are lower now – relative to inflation – than they were in 2016, whereas rents across the rest of New Zealand are up 10 to 15 per cent over the same period.

Building more housing in established suburbs is also cheaper for government: it costs up to $75,000 less to service a dwelling in an established suburb with infrastructure than it does for a new home on the suburban fringe.

Higher density need not come at the expense of liveability, either. Several cities with similar populations but higher densities – such as Vancouver, Toronto and Vienna – outrank Sydney on quality-of-life measures.

Even meeting our climate goals would become easier if our cities become denser, rather than if they continued to sprawl further outwards.

Housing policy winds are shifting

The politics of land-use planning – what gets built and where – have made building more homes in established suburbs hard.

But the good news is that the housing-policy winds are shifting.

Younger Australians are worried that they may never be able to own their own home.

Their parents are worried too: they’re worried that their kids will have to live so far away that they will never get to see the grandchildren; or that they themselves will struggle to find a suitable home in their suburb to downsize into.

It’s no coincidence that in recent years we’ve seen the rise across Australia of the YIMBY movement – or ‘yes in my back yard’ – championing the case for more housing to be built where people want to live and at an affordable cost.

The broad coalition behind Housing Now! – spanning business, unions, think tanks, and community groups – is itself a testament to the common interest we all have in making sure housing is both abundant and affordable.

The National Cabinet housing targets could make housing much more affordable

The recent housing plan agreed by National Cabinet, which set a nationwide target of 1.2 million new well-located homes over five years, reflects the changing politics of housing.

States will be rewarded with a $15,000 payment from the federal government for each extra house they build above their state’s share of a national baseline of 1 million homes.

In the case of NSW, if the national target is pro-rated on the basis of state’s share of the national population, it would mean building an average of 75,000 homes a year over the next five years.

The NSW government would receive $15,000 for every new home built each year above a baseline of 62,500 homes per year, up to 75,000 homes a year.

If NSW can deliver on that target it could mean an extra $1 billion in funding over five years. That funding could support the construction of another 3,000 social housing dwellings across NSW.

More importantly, achieving those targets would mean a large boost to housing supply more generally, making housing substantially cheaper for all NSW residents.

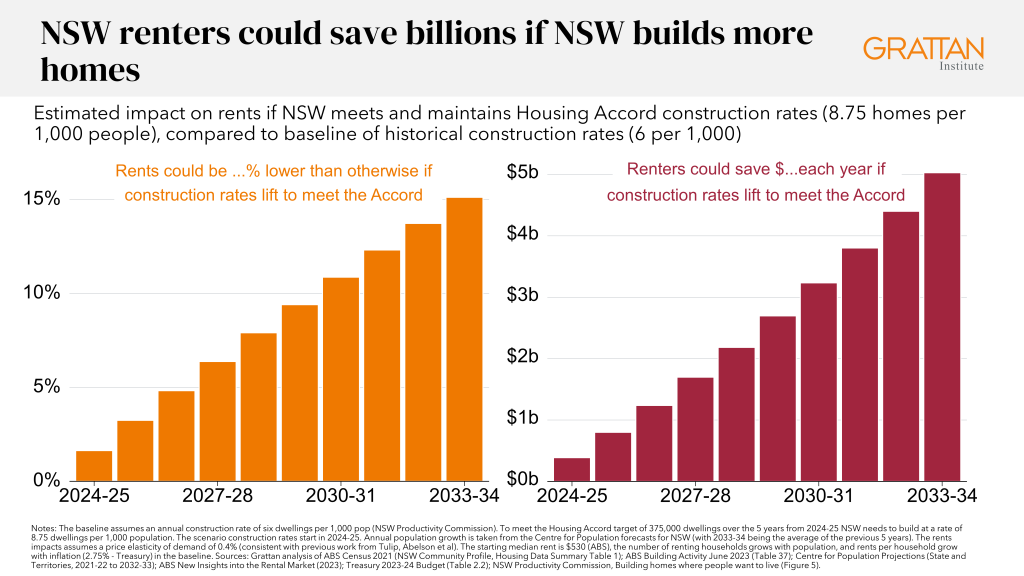

Grattan Institute calculations suggest that building at that rate could reduce rents in NSW from what they otherwise would have been by about 8 per cent after five years. That’s a total saving of $6.3 billion for renters over those first five years.

If those higher rates of construction are sustained for a full decade (and adjusted upward for future population growth), rents could fall by 15 per cent, saving NSW renters $25 billion in total over those ten years.

It’s now up to the NSW government to act

But we’ll only reap the benefits of cheaper housing if governments take the initiative.

The Victorian Government is already taking action. Its recent Housing Statement set a bold target of 800,000 new homes over the next decade, which is more than what it needs to build to meet its population share of the National Cabinet housing targets.

Sydney already loses about 40,000 people annually – disproportionately among young people — who don’t believe they have a future in the city and instead flock to more affordable housing on offer elsewhere.

If the other states succeed in making housing cheaper, it will only further accelerate the ‘brain drain’ out of Sydney.

That is, unless the NSW government also acts.

NSW Premier Chris Minns is making the right noises, calling for Sydney to build up, rather than out.

While the precise actions the government takes should be the subject of more thorough analysis, any serious plan to increase density across Sydney and improve housing affordability in NSW will need to:

1. Reform land-use planning rules – such as by up-zoning scarce inner-city land, or relaxing minimum floor-space ratios – to allow more housing to be built on scarce inner-urban land.

2. Revamp housing targets for local governments and aim to build more housing in more expensive inner-city council areas where many more people want to live.

3. Link councils’ housing targets to local infrastructure funding – for parks, libraries and other amenities – to reward communities that meet their targets.

4. Implement a broad-based windfall gains tax on rezoned land to ensure more of the gains from rezoning are returned to the community.

5. Build more social housing in NSW, at rates at least sufficient to keep pace with population growth, to ensure there is a flow of new social housing for those who need it.

We also need to build better homes

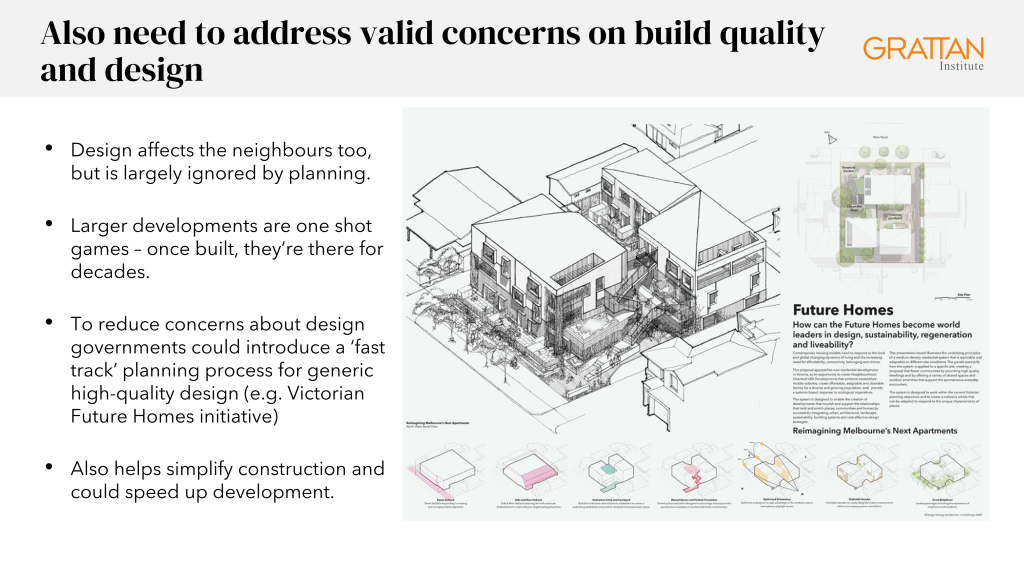

While these reforms would help us build more homes, we also need to build them better.

Public concern about new housing development isn’t just because of NIMBYism. Anyone who looks around the urban landscape in Sydney can see that the quality of much of what we’re building leaves a lot to be desired. And once housing it built, it’s there for decades.

Which is why at the same time as we reform planning rules, we should strengthen both the building code and design rules, to make sure what gets built is built to last, and to live in.

The Victorian Government’s Future Homes Initiative – something Grattan had a hand in designing — saw the government run an architectural competition to canvass high-quality designs for medium-density developments that are then made publicly available to developers.

Developers that adopt one of the award-winning designs secure a faster path through the planning system. The recent Victorian Housing Statement saw the program rolled out across Victoria.

NSW should follow suit.

History shows that residents often value continuity of design and aesthetics.

Many of the neighbourhoods we celebrate today for their liveability were first constructed on the basis of pattern books.

Can it be done?

Some people are naturally sceptical that these housing targets can be met. After all, the NSW government current expects the state to build just 36,000 homes a year over the next five years, which is less than half of what’s needed to achieve the state’s share of the National Cabinet housing plan.

Higher interest rates, spikes in the cost of materials, and a tight labour market are all weighing down new housing starts at present.

But there are good reasons to be optimistic that we can build that many homes in the long term – if we remove the planning barriers, as happened in Auckland.

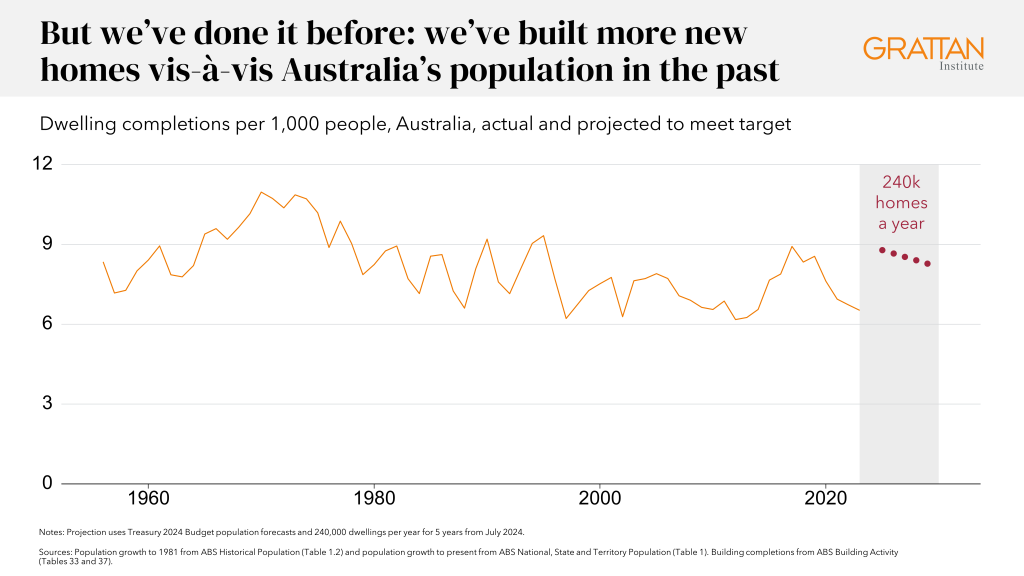

Building the 240,000 homes a year required to hit National Cabinet’s nationwide housing targets would not be unprecedented. In fact, it would only match the rate of construction we achieved nationally in the years just prior to the pandemic.

And Australia’s construction workforce is now more than one third bigger – at 1.3 million workers – than it was at the start of the last housing construction boom in 2016.

Similarly, ramping up housing construction in NSW to 75,000 homes annually would take the state back to the peak in housing construction – at 8.75 homes per 1,000 people – that we saw just before the pandemic. That’s a stretch, but it’s clearly not unachievable.

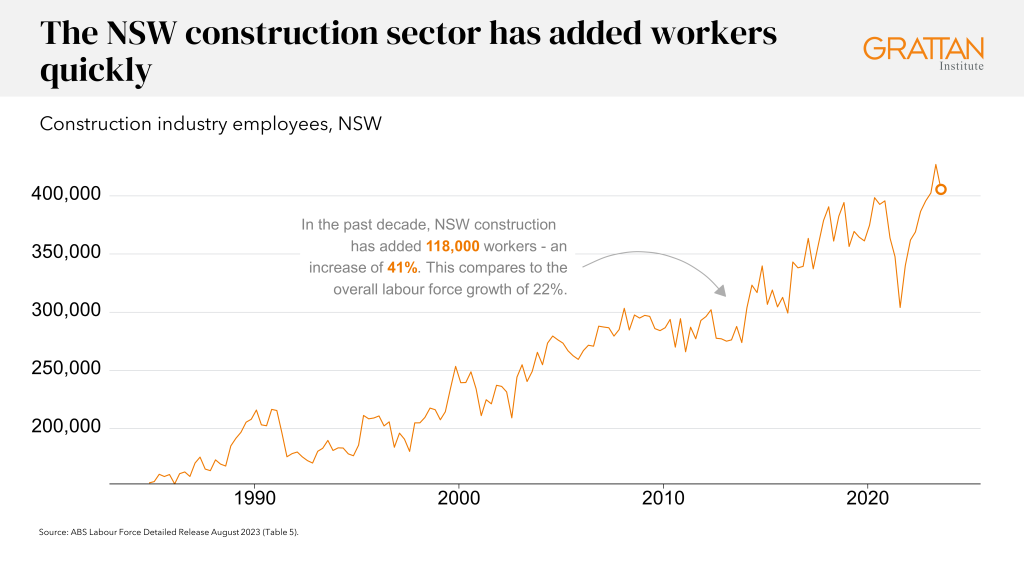

NSW alone has added 118,000 construction workers in the past decade – an increase of 41 per cent, or nearly twice the rate of growth of the total NSW workforce.

The downturn in the construction of commercial office space in the wake of the pandemic is also expected to free up workers to build housing, especially some of those developers pivot to build-to-rent projects.

Of course, housing is competing with other projects and priorities for materials and workers, especially infrastructure and the renewable energy transition. Infrastructure Australia expects spending on major public infrastructure to double between 2020 and 2024.

Which is why we federal and state governments should think very carefully about what infrastructure we really need, especially now that many workers have embraced hybrid work, and cancel those projects that we don’t.

And it’s why the federal government will have to step up its efforts to train and attract more skilled trades workers to Australia.

Governments will have a bigger role to play

Meeting these ambitious housing targets will also require state governments to be more involved in housing construction.

Thanks to recent interest rate rises, housing starts are in the doldrums, at the same time that Australia’s population is surging due to record migration.

State-run developers like Landcom, as well as the burgeoning build-to-rent sector, can help get housing construction moving.

And government developers like Landcom should also pick up awarding-winning designs and use them in the construction of new housing.

In fact, a more active state developer would offer us a better way to support the construction sector in the face of any future recession.

Rather than giving away taxpayer funds to wealthier homeowners so they can put in a new kitchen — as we did with the federal Homebuilder program during the pandemic — the state developer could ramp up projects to support construction activity by building more homes while leaving taxpayers with a valuable asset that can be sold or rented out directly.

Political will is key

Now the steps I’ve outlined today are not easy. But they are necessary if we want more abundant and affordable housing.

NSW has long been the poster child of Australia’s housing affordability woes. But it doesn’t have to stay that way.

Scarce and expensive housing is a problem we really can fix, but only if we – and our governments — make the right choices.

Thank you

The chart ‘NSW renters could save billions if NSW achieves the Housing Accord target’ has been updated since publication. The ‘total saving for renters’ in the following two passages have subsequently been amended from $2.5 billion over the first five years and $10 billion over ten years, to $6.3 and $25 billion respectively.

All blog posts published by the Grattan Institute are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. You may republish our blog posts within the following guidelines.

Brendan Coates

While you’re here…

Grattan Institute is an independent not-for-profit think tank. We don’t take money from political parties or vested interests. Yet we believe in free access to information. All our research is available online, so that more people can benefit from our work.

Which is why we rely on donations from readers like you, so that we can continue our nation-changing research without fear or favour. Your support enables Grattan to improve the lives of all Australians.

Donate now.

Danielle Wood – CEO