Published in Australian Youth Development Index 2020, March 2021

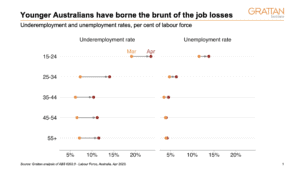

Young workers have borne the brunt of the job losses in this crisis, compounding existing high underemployment with casualisation and stagnant wages that were already hurting the incomes of younger Australians.

Youth unemployment is always higher than general unemployment, but the gap tends to widen during economic downturns. Young workers are more vulnerable because they are less likely to have a foot in the door, have less experience, and are making the transition into employment at a time when fewer jobs are being created.

Youth unemployment rose to 13.8 percent in April 2020, which was double the headline unemployment rate. With more than 20 percent of Australians aged 15–24 also underemployed, more than one in three younger Australians are without paid work or working fewer hours than they would like to.

Even before the crisis, unemployment and underemployment remained stubbornly high for young Australians. The gap between youth employment (15–24) and ‘prime age’ employment (25–54) in Australia has been growing since the global financial crisis (GFC) and was already above the OECD average.70 A study comparing pre- and post-GFC cohorts of young Australians found that even among those who found employment, job quality was inferior for the post-GFC cohort in terms of job security, hours of work, and earnings.

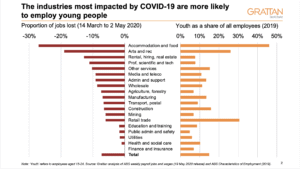

In an already weak youth labour market, the COVID-19 crisis hits doubly hard. Young workers are already more vulnerable; on top of that, the businesses most affected by social distancing restrictions are those most likely to employ young people, including restaurants, bars, retail outlets, gyms, and recreation and tourism businesses.

The biggest concern is the potential for long-term damage to the health, wellbeing, and future earnings of young Australians. The economic gap between young and old was already large and growing, especially in incomes, wealth and spending. This crisis has the potential to substantially exacerbate intergenerational inequality in Australia.

Governments have helped to soften the blow, at least temporarily, through schemes such as JobKeeper and additional financial support for JobSeeker. But if governments attempt to consolidate their budgets too soon, the economic recovery will be slower, hurting job prospects particularly for younger people.

As governments consolidate budgets in future years, not all the hard work should be done through income tax, otherwise, young people will pay twice: first in the initial employment shock, and second with a higher tax burden through their careers. Winding back some of the generous tax breaks for older Australians that serve little policy purpose would be a better way to ensure that the economic cost of coronavirus does not just fall on the shoulders of the young.