Published in Inside Story, 2 October 2020

Tuesday’s federal budget will be one of the most important in decades. Australia is mired in recession. The Reserve Bank expects unemployment to hit 10 per cent by Christmas. Treasury apparently expects unemployment to remain above 6 per cent for the next half-decade.

But with the Reserve Bank’s cash rate now close to zero, its conventional monetary policy armoury is effectively out of ammunition. While the Bank can and should do more using unconventional monetary policy, it alone can’t pull us out of the hole. Responsibility for getting Australians back to work inevitably shifts to fiscal policy, and to the federal treasurer.

So how should we judge whether the budget does what’s required? The first step is to acknowledge the scale and duration of the stimulus we need.

Recessions are incredibly costly. If the output grows in line with official projections over the next half-decade, Australia will be left with a cumulative output gap — the difference between actual and potential economic activity — of about $530 billion. The average Australian will be about $21,000 worse off over those five years than if the economy were operating at potential.

Recessions don’t just hurt while you’re in them. They leave scars that can be painful for years. Recent papers from Treasury and the Productivity Commission reaffirm that young people who enter the job market in a period of high unemployment have poorer employment prospects and lower wages for many years down the track.

Faced with this scenario — a long and deep recession with sluggish recovery — the Morrison government should do everything in its power to stimulate the economy.

At Grattan Institute we recently estimated that further fiscal stimulus of between $100 billion and $120 billion will be needed to bring unemployment back below 5 per cent by the end of 2022. That would mean an extra 600,000 to 700,000 Australians back in work, and most workers would also have a fighting chance of getting their first real pay rises in close to a decade.

Not all of this stimulus needs to be announced in this budget. Nor should Canberra bear the full burden of getting us out of this crisis. But the federal government taxes and spends more than all the states combined, and can borrow at cheaper rates than the states, so it makes sense for it to shoulder much of the burden.

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg made a welcome policy shift last week, signalling significantly more fiscal stimulus “to drive the unemployment rate down as fast as possible.”

Just as important will be avoiding the temptation to turn off the fiscal taps too soon. Fiscal policy is now the main macroeconomic policy lever. So the right stance now is not so much “limited and temporary” as “whatever it takes for as long as it takes” — until, that is, global interest rates begin to rise and the Reserve Bank is no longer constrained.

The treasurer has pledged to keep running deficits “until the unemployment rate is comfortably back under 6 per cent,” at which point he’ll flick the switch to budget consolidation. That’s too soon.

Rushing too quickly to “repair” the budget position would be an economic own goal. It would pull support away before unemployment has fallen far enough to spark broad-based growth in wages.

The treasurer should wait until we see a sustained lift in inflation and wages — which is only likely when unemployment falls below 5 per cent — before taking his foot off the gas.

Beyond the quantum of stimulus, the selection and design of the measures matters too.

Five big considerations should guide the treasurer’s thinking.

First, stimulus should fill the hole in economic activity left by Covid-19 as cost-effectively as possible. While governments can borrow cheaply today — at interest rates well below 1 per cent — the debt must ultimately be repaid.

The cost effectiveness of stimulus can be measured by the fiscal multiplier: the increase in economic activity arising from a dollar of stimulus. As the table shows, not all stimulus options are created equal. Government investment and consumption are usually the most effective forms of short-run stimulus, tax cuts the least. Cash transfers to the households most likely to spend the money — mainly those on low incomes — are somewhere in the middle.

The estimates in the table assume that the impact of stimulus is offset in time by the Reserve Bank. But multipliers are likely to be much higher when the central bank can’t or won’t offset stimulus by raising interest rates. When interest rates are at zero, studies suggest multipliers in the $1.50 to $2.50 range for Japan for each dollar of stimulus and about $1.50 for the United States.

Some studies find that when interest rates are as low as they can go, government spending multipliers can be three or even four times larger than in normal times, although multipliers on tax cuts still tend to be lower. By contrast, our estimates of stimulus needs assume a boost to GDP of between 80 cents and $1 for every dollar of stimulus.

Second, government investment and consumption plans should be targeted at job-rich sectors, and at sectors with the most spare capacity. After all, the purpose of stimulus is to get people back to work, both during and after the crisis.

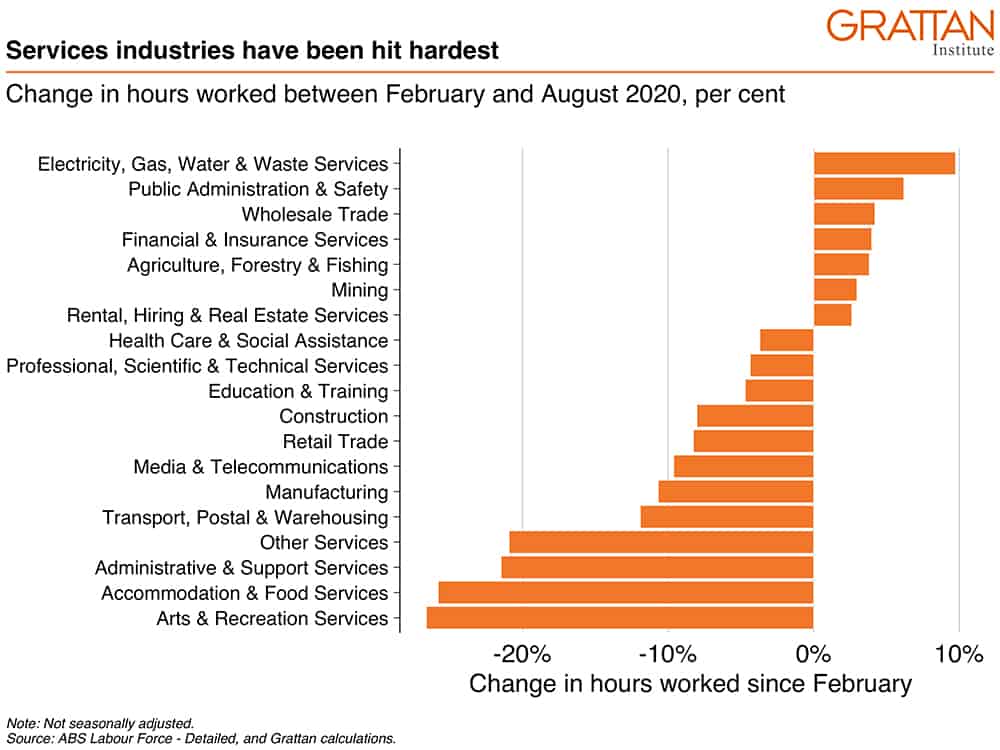

Not every industry has the same need for support. The services industries have the most spare capacity, with those hit hardest by the pandemic — hospitality and the arts — experiencing reductions in hours worked of more than 20 per cent since February. Administration and other services aren’t far behind.

By contrast, hours worked have increased in some industries, including utilities and public administration. Many large infrastructure projects tend to create fewer jobs per million dollars. And some states, such as Victoria, already have such a big pipeline of large projects that little capacity exists to deliver more.

Third, stimulus should involve “no regrets” — in other words, the spending should have a solid rationale and provide good value for money to the community.

Plenty of opportunities exist for stimulus spending to fulfil the virtuous trifecta of long-term social, economic and environmental benefits. But many commercial and ideological interests are seeking to align governments’ post-pandemic investment priorities with their vested interests. Spending big on the wrong projects could leave us all worse off.

Boosting infrastructure spending, for instance, is often nominated as an effective stimulus measure because it has high fiscal multipliers and adds to the productive capacity of the economy. But infrastructure decisions, many of them measured in the billions of dollars, are too often based on politics rather than economics. What’s more, the Covid-19 crisis almost certainly means long-term changes in patterns of work and travel, as well as lower population growth. So the pre-Covid pipeline of city-shaping transport infrastructure projects may no longer make sense.

Proposed infrastructure projects should be subjected to rigorous, like-for-like cost-benefit analysis. And existing business cases should be reviewed – using lower discount rates to reflect record low interest rates — to ensure they are robust to a range of post-Covid scenarios.

Fourth, governments should design stimulus policies in a way that doesn’t block, and preferably facilitates, long-run structural change.

Recessions tend to accelerate structural changes in the economy, and this one is no exception. Covid-19 has already caused big shifts to online shopping and working from home, for example — and many such changes will be permanent.

One estimate suggests that 42 per cent of the initial layoffs in the United States will ultimately become permanent. A recent Australian Bureau of Statistics survey suggests 10 per cent of small businesses and 6 per cent of medium businesses expect to close when support measures end.

There will inevitably be a lag between when old firms close and new firms open. Government should do everything in its power to facilitate that structural change, without letting aggregate demand fall in a hole.

Fifth, government should aim to minimise the number of otherwise viable businesses that fail because of the short-term impact of the pandemic. Thus far, fewer Australian businesses have gone into insolvency this year than last. JobKeeper, cashflow supports, the commercial rental code of conduct, loan deferrals and changes to insolvency laws have enabled many businesses to hang on by their fingernails — for now.

But this crisis is far from over, including for many sectors with a strong future. There are good reasons to expect tourism, the arts and hospitality to remain significant parts of the economy after the pandemic. Well-run firms in the affected sectors should not be consigned to death by way of inadequate support during the crisis.

Australia needs a judicious mix of policies specific to the hardest-hit sectors; flexible, sector-blind support policies that automatically responds to need; and general support focused on business and employment growth that isn’t limited to incumbents. As health restrictions are eased and the economic situation morphs into a conventional recession, the weight of support should naturally shift from the former to the latter.

So, what would good stimulus look like?

Building social housing should be at the top of the list, because that would help cushion the coming crunch in the construction sector and tackle an important unmet social need. We recommend building at least 30,000 new social housing units, at a cost of more than $10 billion.

Depending on the economic situation, further supports for hard-hit firms might be required beyond March. A hiring subsidy to replace JobKeeper next year would help get Australians off the unemployment rolls faster. And extending the instant asset write-off into 2021, or adopting an investment allowance (in effect, granting greater than 100 per cent depreciation), would also encourage firms to invest.

Bringing forward personal income tax cuts can help boost spending, but some of the money will inevitably “leak” to savings, reducing the economic kick. The “stage three” tax cuts are particularly poorly designed for stimulus because they mainly go to high-income earners, the group most likely to save the additional income. Almost two-thirds of the stage three benefits flow to the top 20 per cent of tax-filers, and in recent months this group has been saving at record rates.

Time-limited vouchers to boost spending in hard-hit sectors such as hospitality and tourism would provide a bigger short-term boost to the economy per government dollar spent. The Northern Territory and Tasmania have launched time-limited vouchers for spending on local tourism.

So would permanently increasing the JobSeeker unemployment benefit and rent assistance. The latter are not traditional temporary stimulus measures, but extra income assistance for the poorest is long overdue.

And the treasurer should announce more spending on services, particularly in areas of social need such as mental health, aged care and catch-up tutoring for students who fell behind when schools were closed during the crisis. Increasing the childcare subsidy would be a significant reform in its own right, and would boost employment in the sector.

Looking further ahead, the federal government will need to ensure its debt doesn’t continue to rise as a share of the economy.

With historically low interest rates, it isn’t necessary to run budget surpluses to stabilise and reduce debt as a share of GDP, provided the economy is growing steadily. But consolidation — via higher taxes and lower spending — will eventually be needed.

The nature and timing of any budget consolidation will ultimately determine who pays for the Covid-19 hit. And that will involve even harder choices than those the treasurer is grappling with this week. But the time for making those decisions still seems a world away.