Published at The Conversation, 10 November 2020

The government has targeted its JobMaker Hiring Credit too narrowly.

The scheme to go before the Senate this week will give employers who take on someone aged 16 to 29 years who has been on JobSeeker or a related benefit a bonus of A$200 per week, and a bonus of $100 per week if the person is aged 30 to 35 years.

New hires older than 35 won’t attract a bonus, and nor will new hires who have been out of work but not on JobSeeker.

The bonus will last for up to a year.

There are reasons to focus on young people. Youth unemployment is 14.5%, almost double the economy-wide average, and young people have lost more working hours than older people.

Also, young people will arguably be scarred for longer by the experience of unemployment (although many older people will be scarred for just as long or longer, never returning to work).

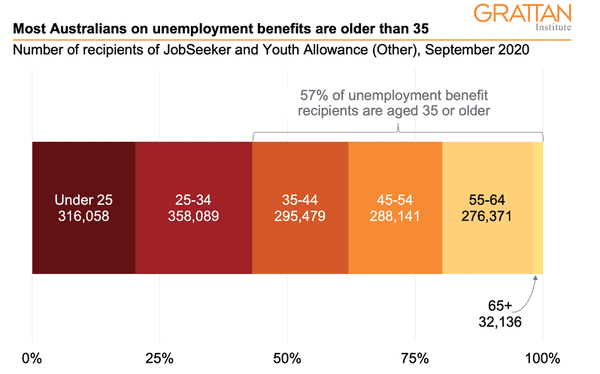

But Australians aged 35 and younger make up less than half of those on JobSeeker.

Most – about 800,000 of the 1.5 million – are older than 35.

With Victoria reopening, summer coming and the treasurer talking confidently about “fighting back”, it is easy to forget how serious our unemployment problem is.

Unemployment is at 6.9%, the highest it’s been this century. If the thousands working zero hours on JobKeeper were included, it would be higher still. Even without including those people, treasury the unemployment rate to reach 8% by Christmas.

Official forecasts say unemployment won’t fall to 5.5% for three-and-a-half years, until mid 2024, an extraordinarily slow recovery by the standard of previous downturns.

JobMaker as presently configured won’t do enough to speed it up.

The budget speech said the hiring credit would support around 450,000 jobs , but treasury has since told a Senate hearing that only about 10% of those jobs will be jobs that wouldn’t have been created anyway – about 45,000.

In our submission to the Senate inquiry into JobMaker we recommended four fundamental changes.

1. Open it to all ages

Opening the scheme to new employees of all ages, not just those age 35 or younger, could more than double the reach of the scheme.

It would also roughly double its cost, from $4 billion to roughly $8 billion, but that cost would remain modest in the context of the government’s stimulus spending to date.

Targeting younger workers would make sense if expenditure needed to be highly constrained, but with a need for more government spending rather than less there is no point in making the subsidy available to only some of the people who could benefit from it.

2. Extend it beyond the unemployed

Limiting the credit to jobs filled by new hires who have been on JobSeeker or a related payment is unnecessarily constraining.

If the most suitable candidate for a role is already employed, hiring that person provides an opportunity for someone else to fill their old position. If it is a new job, it is likely to ultimately put an unemployed person into work.

The goal ought to be to strengthen overall labour demand, not to encourage only the subset of job creation where the new job happens to be a good match for someone presently unemployed.

3. Allow more employers to use it

The scheme requires employers to demonstrate that new hires have boosted payroll beyond where it was in the three months to September 30 2020.

But the payroll baseline is defined as including jobs supported by JobKeeper.

As firms become ineligible for JobKeeper, and the payment rate is reduced in January and again in March, many businesses that relied on the payment will have to lay off staff. As a result, they will have an actual payroll bill well below where it was in the three months to September 30 2020.

This will effectively exclude them from the scheme, giving them no extra incentive to retain staff as they come off JobKeeper, or to increase working hours or hire more staff as conditions improve.

The government should ease the criteria to require employers to only demonstrate that they have boosted payroll net of JobKeeper receipts.

4. Ban ‘harvesting’

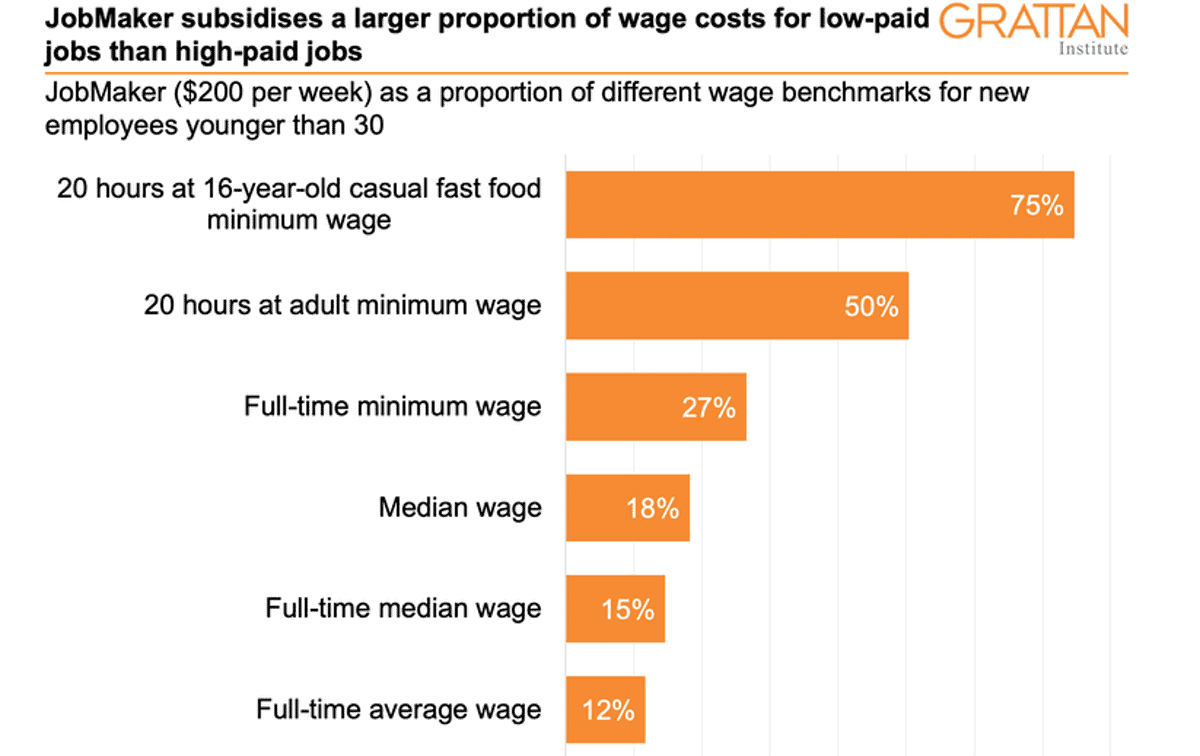

The test should be more demanding. As designed, employers can claim back up to 100 per cent of an increase in their payroll, which creates incentives for employers to “harvest” credits by converting full-time jobs to part-time.

As an example, an employer who reduces the hours of an existing employee from 40 per week to 20, while hiring two new employees at 20 hours each would be able to claim the hiring credit twice – despite total hours worked and wages paid increasing by only one 20 hour job.

This could be fixed by requiring each new hire to boost payroll by a multiple of credit paid.

A better, simpler model

A better model would be to simply pay employers a proportion of their payroll growth, as proposed by economist Peter Downes.

Our calculations suggest that as presently designed JobMaker will skew employment towards lower-wage, part-time jobs.

A rebate on additional payroll would instead encourage employment growth of all types – full-time as well as part-time, and extra hours worked by existing staff.

But even such a better-designed credit won’t help much if there’s weak demand for workers. To get it, we will need more stimulus, more government spending.

Either way, we’re going to have to boost the economy

Our estimate is that an extra $50 billion would drive unemployment down to 5% and kickstart wage growth nearly two years ahead of the government’s schedule.

There are plenty of good options for doing it, and a more ambitious JobMaker is one of them.

![]()