Australia’s debates about migration policy tend to focus too much on the size of the intake, and not enough on who we choose. But there are plenty of opportunities to make Australia’s migration program work better, rather than just making it bigger.

After a decade of neglect, Australia’s skilled migration system is finally back in the headlines. The reason is obvious. Unemployment is now 3.4 per cent – the lowest level in 50 years – and there are more than 500,000 job vacancies across the country. Many Australian businesses are screaming out for more workers.

The substantial backlog in unprocessed visas has attracted a lot of media attention. But as the Jobs and Skills Summit meets next week, managing the visa backlog should be just the first of several migration reform priorities.

Increasing permanent skilled migration won’t address skills shortages

Business groups want the government to lift Australia’s annual permanent migration intake to 200,000, an increase of 40,000. The federal government appears set to heed their call. But it’s worth being clear exactly what problem a higher migrant intake would solve.

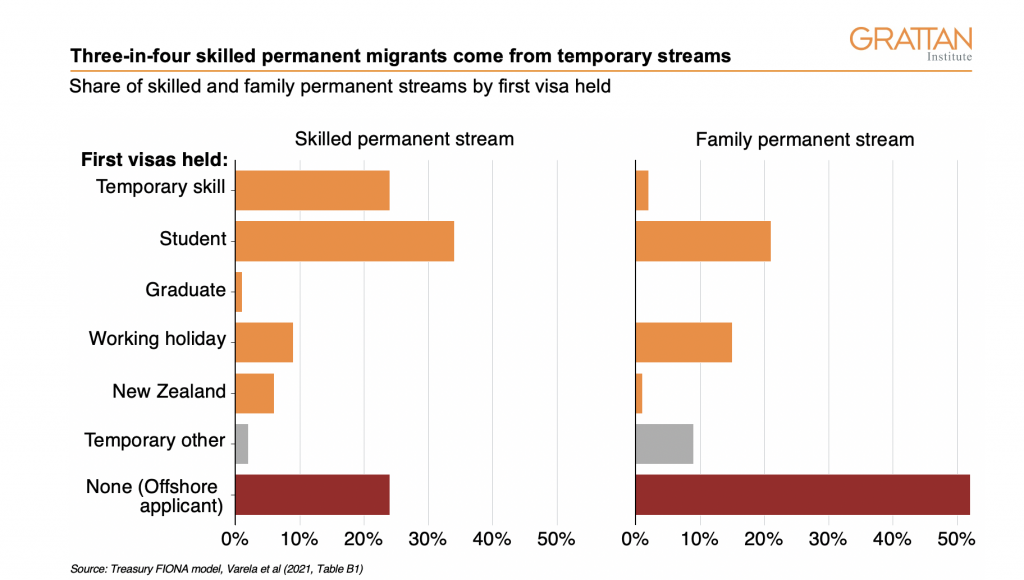

An increase in Australia’s permanent skilled migrant intake – currently 110,000 a year – would do little to tackle widespread skills shortages. That’s because more permanent skilled migrants won’t mean many more workers in Australia, at least not straightaway. Three quarters of permanent skilled visas are allocated to people already here on a temporary visa. More permanent visas essentially means that fewer temporary visa holders end up leaving.

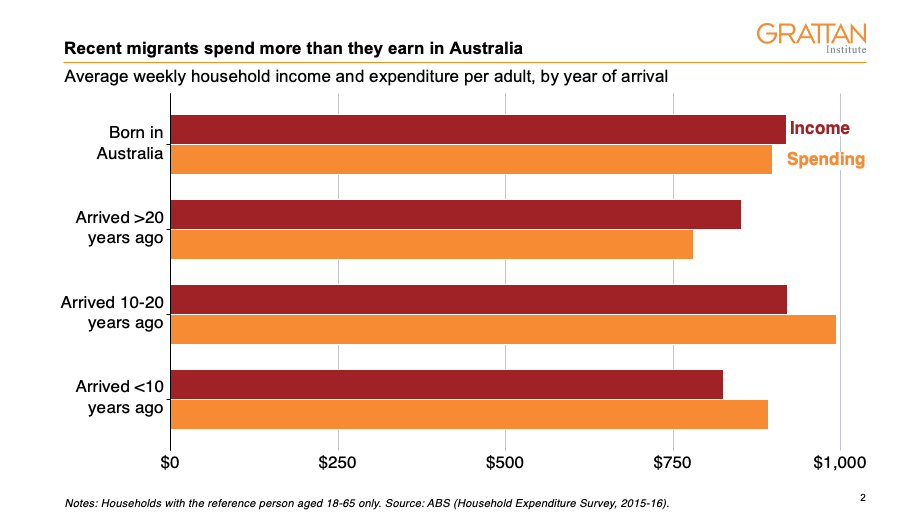

Even if priority is given to skilled visa applicants from overseas – as the government plans – more permanent migrants arriving on our shores won’t cool Australia’s ultra-hot jobs market. When there are more migrants there are also more jobs. Recent migrants spend more in Australia than they earn, adding as much to labour demand as labour supply. That’s why studies repeatedly find migration has little to no overall impact on the wages of local workers.

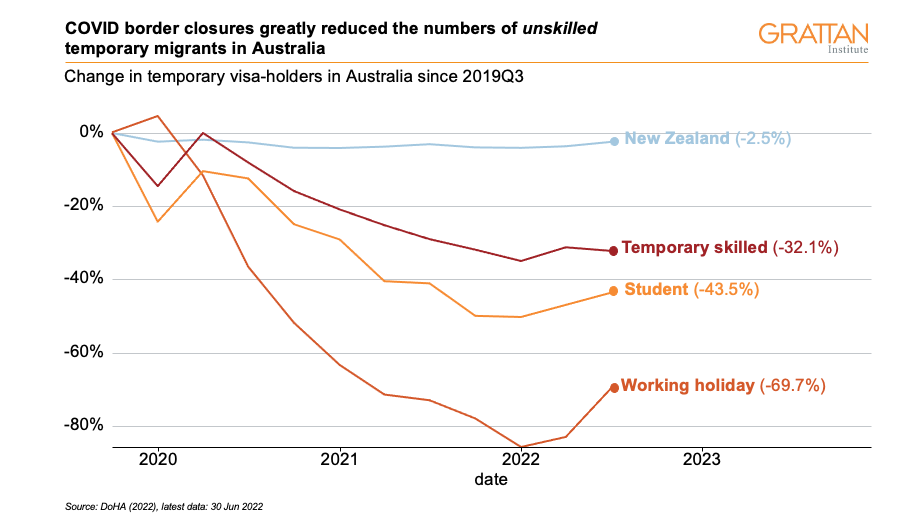

But even a targeted program won’t make up for the fact that most of the migrants missing from the Australian labour market don’t come here on permanent visas.

The number of student and working holiday visa-holders plummeted when our borders were shut in 2020 and 2021, and those numbers have yet to recover. These visa-holders work in some of the industries suffering the worst labour shortages, such as food and accommodation services. But permanent skilled migrants generally don’t work in hospitality and tourism where wages are low; instead, they tend to work in high-wage industries such as professional services and finance.

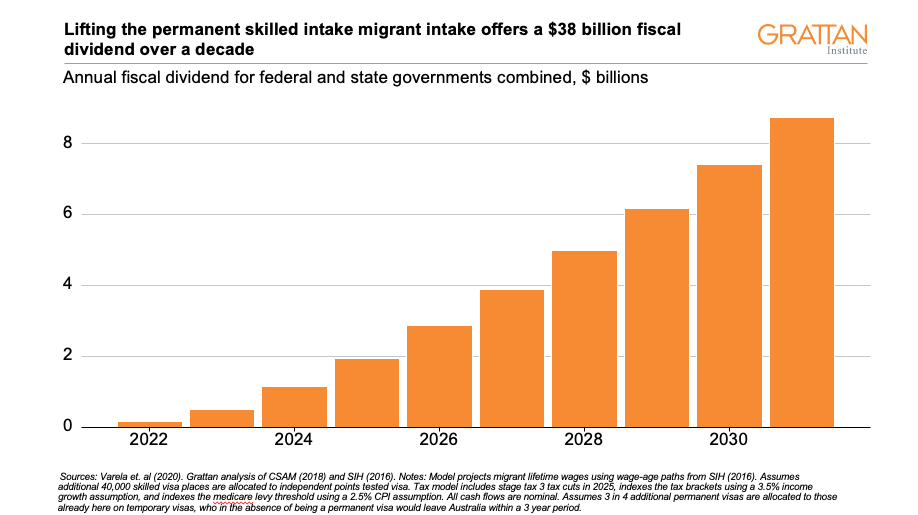

Increasing the permanent intake offers a big fiscal dividend

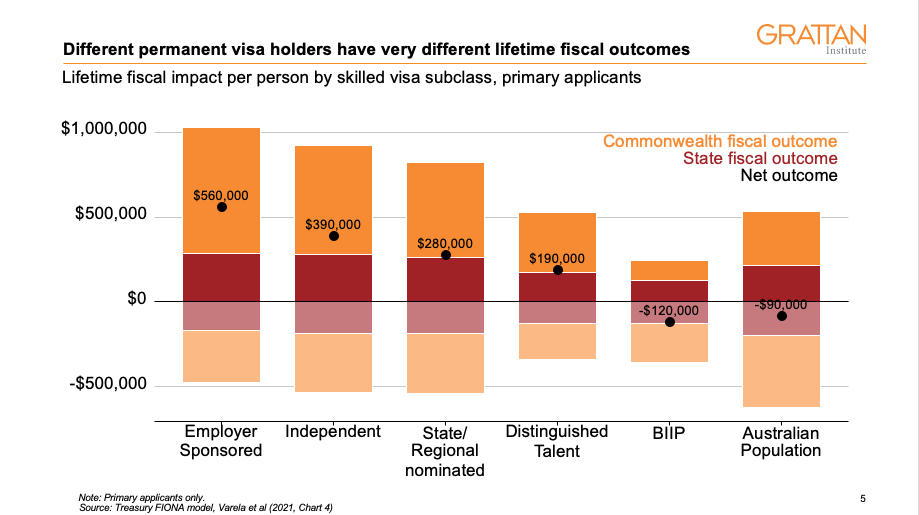

Instead, the main benefit of lifting the annual migrant intake would be to boost federal and state government budgets that are mired in debt. Skilled migrants generate a fiscal dividend because they pay more in taxes than they receive in public services and benefits over their lifetimes.

Grattan Institute modelling suggests that increasing the size of the permanent intake from 160,000 to 200,000, and allocating those extra visas to skilled workers, could offer a $38 billion boost to federal and state governments combined over the next decade.

Extra young, high-skilled migrants provide a fiscal dividend to the Australian community since they earn high incomes and pay substantial taxes upon arriving in Australia. While immigration does not eliminate the costs of population ageing, since migrants themselves also age, even in the long term each additional cohort of 40,000 skilled migrants would deliver a $7 billion fiscal dividend to federal and state governments combined over their lifetimes in Australia after accounting for pensions, health and aged care, and other costs.

But a higher migrant intake means higher housing costs

But raising the intake would also add to demand in Australia’s already tight rental markets, especially as housing supply has failed to keep pace. Reserve Bank researchers estimated that the high migration in the first decade of this century saw housing rents rise 9 per cent higher by 2018 than if population growth had stayed at 2005 levels.

We estimate that increasing the annual migrant intake by 40,000 a year would, over a decade, lift rents by up to a further 5 per cent. Lower-income renters would be hit hardest. For that reason, any increase in the annual migrant intake must be paired with a renewed federal commitment to boost housing supply in our major cities, and an immediate 40 per cent boost to Commonwealth Rent Assistance.

Improving the composition of our permanent skilled migrant intake

However, the number of migrants is just one part of migration policy – just as important is which migrants we choose.

As the Grattan Institute’s 2021 report Rethinking permanent skilled migration showed, people who gain a permanent skilled visa to Australia typically live and work here for many decades. This means policy decisions affecting who gains a visa in the first place can have compounding effects over many years.

Indeed, a more selective approach to allocating permanent visas would produce many benefits without any of the costs of a larger intake.

For instance, the Business Investment and Innovation Program (BIIP), which offers 9,500 permanent visas a year to migrants who establish businesses or invest in Australia, should be abolished.

Few investors on BIIP visas are financing projects that would not otherwise occur. Few are providing entrepreneurial acumen that will benefit the Australian community, because they are typically less skilled than other migrants and speak little English. Treasury estimates that, on average, each BIIP visa holder costs the Australian taxpayer $120,000 over their lifetimes because they tend to be older and earn much less than other skilled migrants.

Visa places freed up by abolishing the BIIP should be reallocated to different skilled-worker visa categories via employer sponsorship or the points test. We estimate that this would boost the fiscal dividend from Australia’s skilled migration program by $3 billion over the next decade and by much more in the long term. Prioritising high-skill, high-wage workers for permanent visas is also a better way to encourage innovation in technology and business practices.

Target wages, not shortages, for permanent skilled visas

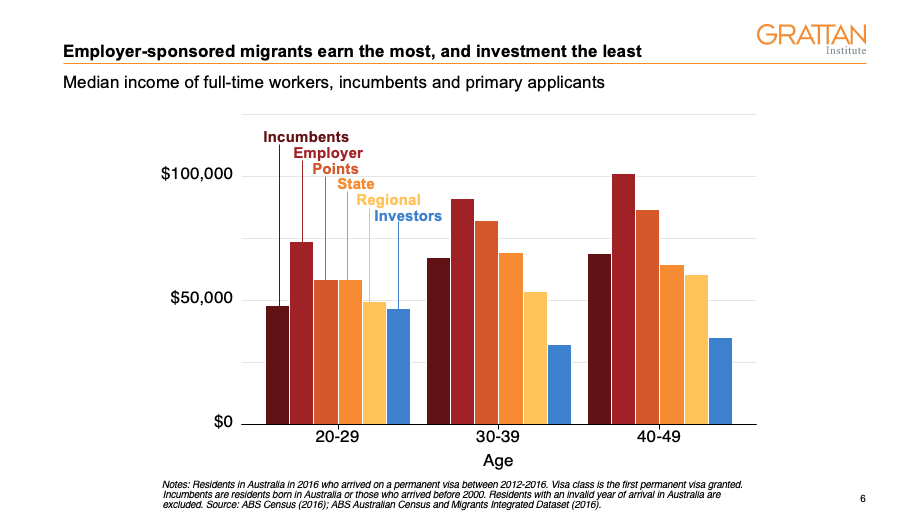

Swapping business visas out for more skilled-worker visas is a vital first step. The next is to target migrants who can fill high-wage jobs rather than specific occupations.

Currently, employers can only sponsor people into jobs only when their occupation is deemed eligible by being listed on an approved occupation list. It’s an approach that makes sponsoring workers much slower and more complex than it needs to be.

It means, for example, that a data scientist cannot be sponsored for permanent residency in Sydney, and a multinational technology company is forced to treat software engineers and data scientists differently because of their occupation. A mining company cannot sponsor many machinery operators regardless of what it pays them.

The policy should be changed because jobs, and the wages they offer, are a better guide to skills than ‘occupations’. Rather than drawing up lists of occupations that would benefit from skilled migrants, the government should assess which migrants bring valuable skills simply by looking at the wages their jobs attract.

If Australia introduced a wage threshold of $85,000 a year – the equivalent of median annual full-time earnings – we could stop relying on those clunky and out-of-date occupation lists and instead focus on what matters: the wages employers are willing to pay to workers. The government could trial the change by opening skilled migration to all occupations for jobs paying at least $130,000 a year – or 1.5 times median full-time earnings.

Rethinking permanent skilled migration along these lines would simplify the sponsorship process and provide greater certainty for both firms and would-be workers. Firms would no longer need to fit the sponsored role into a particular listed occupation, making visa applications both simpler and faster to process.

Review points-test visas

Points-tested visas should be independently reviewed to ensure they prioritise younger, higher-skilled workers. Points should be allocated only for characteristics that suggest an applicant will succeed in Australia. The review should also consider whether separate state-nominated and regional points-tested visa streams should be removed, since those visas tend to select less-skilled migrants who earn lower incomes in Australia.

Raise the bar for temporary skilled migration

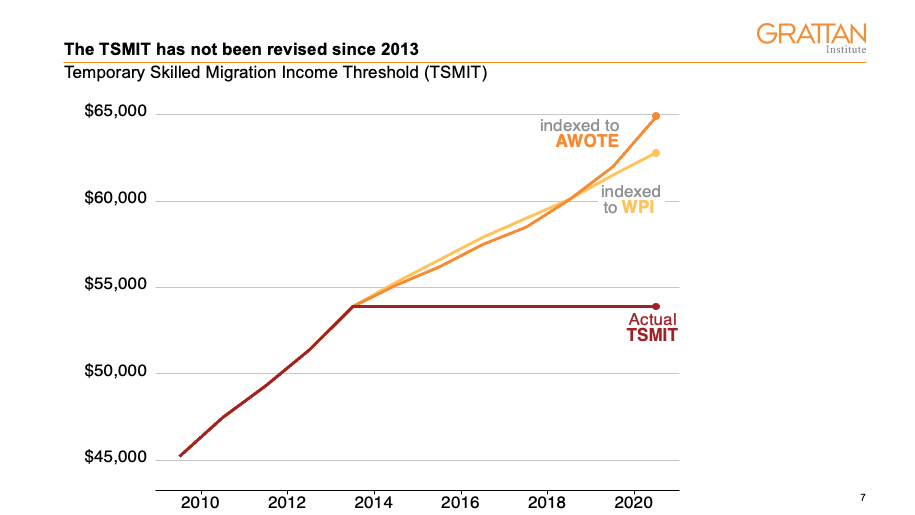

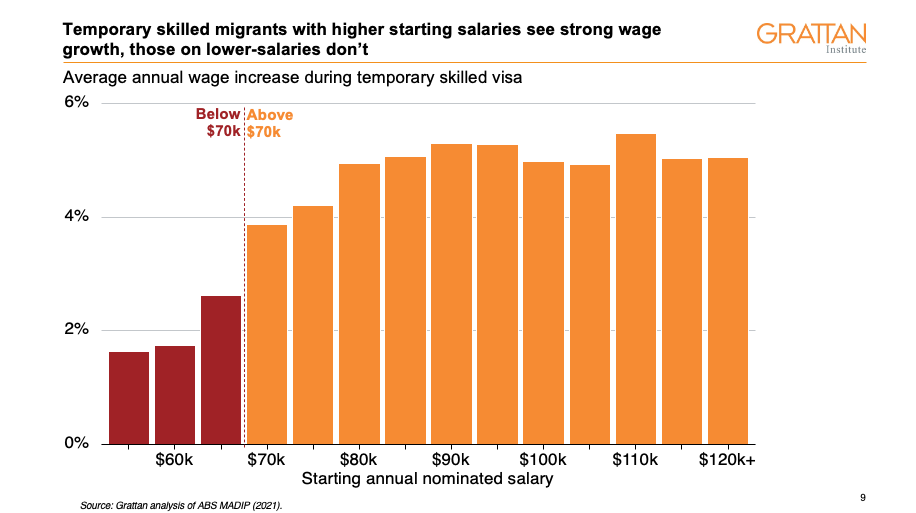

Similarly, the federal government should raise the minimum salary threshold for sponsoring temporary skilled migrants to $70,000, while allowing employers to hire temporary skilled migrants into jobs in any occupation, provided they are paid the same as equivalent Australians doing similar jobs.

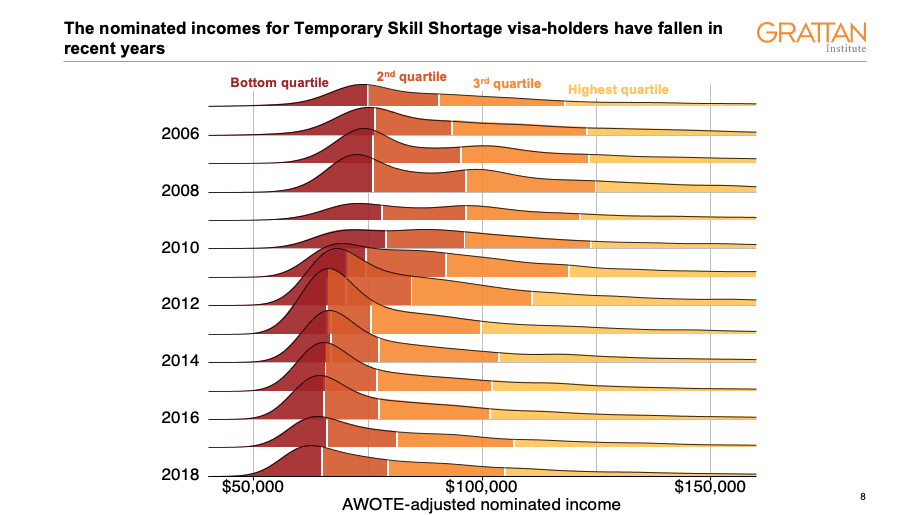

The minimum salary threshold sponsoring temporary workers of $53,900 a year – frozen since mid-2013 – has allowed employers to sponsor a growing number of low-wage workers with few skills. Today, more than half of sponsored workers earn less than the typical full-time Australian worker (currently $85,000 a year). In 2005 just 38 per cent did. A $70,000 wage threshold is not a radical proposal: the wage threshold would already be $65,000 today if it had tracked wages since 2013.

Targeting higher-wage migrants will better address most genuine skills shortages that emerge, since most shortages should arise where workers take more time to train, which are the same jobs that attract higher wages.

Exclusively targeting high-wage jobs for temporary sponsorship would mean less red tape for sponsoring employers, especially since high-wage workers are at much less risk of being exploited. Temporary sponsored visas should be made portable, so temporary skilled migrants could walk away from employers who mistreat them, or find a better job once in Australia. Meanwhile labour-market testing doesn’t work and should be scrapped, making it faster for firms to sponsor workers.

Limiting temporary sponsorship to high wage jobs would make it easier to offer pathways to permanent residency for temporary skilled migrants, making Australia a much more attractive destination for talent. Workers on temporary visas earning at least $70,000 a year could be confident of becoming permanent residents once they earn above $85,000 a year.

About one in three existing jobs for temporary skilled migrants would be knocked out by a $70,000 wage threshold. Hospitality would be hit hardest, since nine in 10 cooks and chefs are paid less than $70,000 a year. But it was allowing employers to sponsor workers at such low wages which has raised community concerns about temporary migration in the first place. Our research shows that sponsored workers on lower wages tend not to see their wages rise once in Australia – reflecting their lack of bargaining power – whereas higher-wage temporary migrants do get pay rises.

Wages in hospitality would have to rise, benefiting local workers. But other sectors, such as health and aged care, would be barely affected since few temporary sponsored migrants currently work in those sectors.

Some may worry that restricting low-wage jobs from temporary sponsorship will make it harder for Australia to manage skills shortages arising from COVID border closures. But temporary sponsorship has never been permitted for the baristas or farm hands that employers are now struggling to find. These shortages will ease as the many students and working holiday makers that used to do these jobs return to Australia.

Australia’s debates about migration policy tend to focus too much on the size of the intake, and not enough on who we choose. But there are plenty of opportunities to make Australia’s migration program work better, rather than just making it bigger.

Brendan Coates

While you’re here…

Grattan Institute is an independent not-for-profit think tank. We don’t take money from political parties or vested interests. Yet we believe in free access to information. All our research is available online, so that more people can benefit from our work.

Which is why we rely on donations from readers like you, so that we can continue our nation-changing research without fear or favour. Your support enables Grattan to improve the lives of all Australians.

Donate now.

Danielle Wood – CEO