Published at The Conversation, Tuesday 13 March

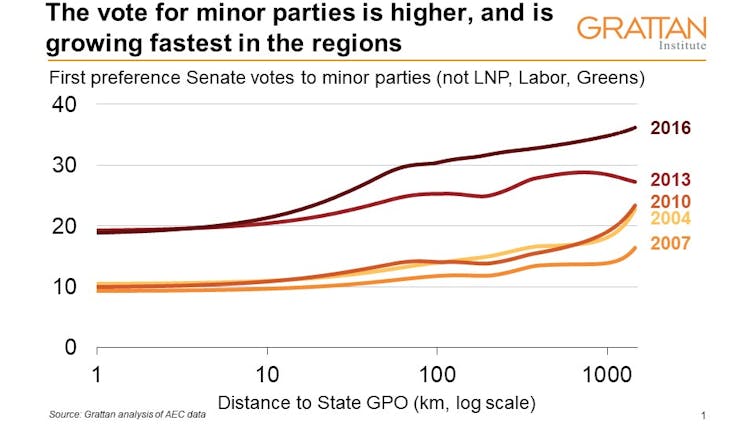

Protest politics is on the rise in Australia. At the 2016 federal election, votes for minor parties hit their highest level since 1949. More than one in four Australians voted for someone other than the Liberals, Nationals, ALP or Greens in the Senate, and more than one in eight did likewise for the House of Representatives. First-preference Senate votes for minor parties leapt from 12% in 2004 to 26% in 2016.

The major parties are particularly on the nose in the regions. The further you drive from a capital city, the higher the minor party vote and the more it has risen.

Grattan Institute

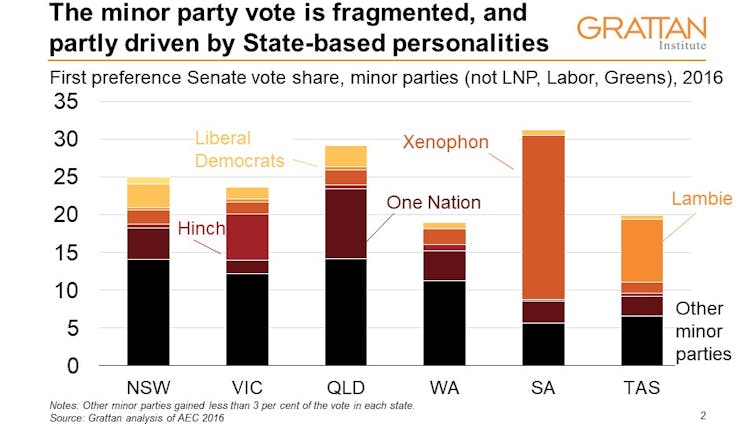

What’s going on? A new Grattan Institute report finds that the minor party vote is mostly a protest against the major parties. It’s a vote for “anyone but them” in favour of a diverse group of parties, often headed by “brand name” personalities.

Grattan Institute

So why are Australian voters angry? And why are they particularly angry in the regions?

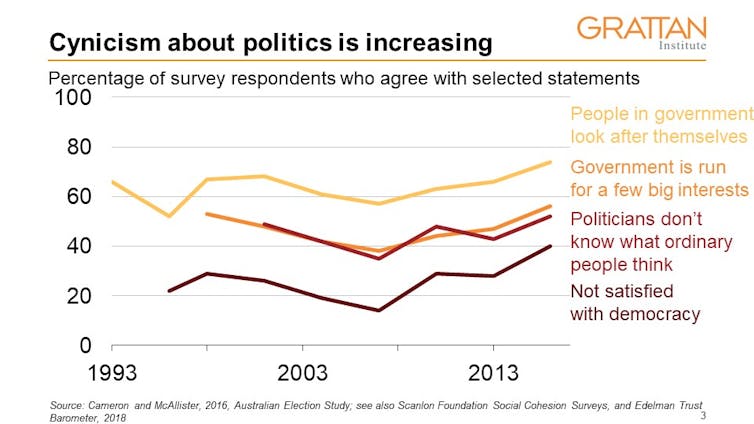

Falling trust in government explains much of the dissatisfaction. Since 2007, there has been a significant increase in the share of people who believe that politicians look after themselves and that government is run by a few big interests.

Grattan Institute

The growing belief that government is increasingly conducted in the interests of the rulers rather than the ruled feeds voter disillusionment. Minor party voters have less trust in government than those who vote for the majors. And outsider parties have tapped into these concerns with their promises to “keep the bastards honest” and to “drain the swamp”.

Economic factors are less important than you might expect. The rise in the minor party vote doesn’t seem to be about stagnant wages or rising inequality: the vote grew most strongly when real wages were rising but inequality wasn’t. And the biggest increase in the minor party vote was between 2010 and 2013 – when Australians were more optimistic about their immediate financial future than at any other point in the past 15 years.

But economics is still relevant. The minor party vote increased as unemployment rose, and minor party voters are more likely than others to have negative views about globalisation and free trade. The protectionist economic policies of many minor parties may therefore account for some of their appeal. And some of their anti-globalisation and “Australia first” rhetoric also taps into broader cultural anxiety about the pace and direction of change.

Many minor parties appeal to voters who don’t like the way our society is changing. Minor parties want to protect the cultural symbols and narratives associated with “traditional Australia”. They are more likely to oppose changing the date of Australia Day, for example.

These views are particularly prominent among One Nation voters: more than 90% of them strongly agree that maintaining an Australian way of life and culture is important. They are also much more likely to be sceptical about the benefits of immigration: about 50% of One Nation voters believe that multiculturalism has not been good for Australia, compared with 15% of Liberal/Nationals voters (the next highest group).

This sense of being left behind by the pace of economic and social change is more prevalent in regional Australia, where the minor party vote is higher and growing faster. Regions hold a falling share of Australia’s population and therefore of Australia’s economy.

At the same time, Australia’s cultural symbols are becoming more city-centric: less about mateship and more about multiculturalism. People in regional areas are sensitive to this cultural change and are attracted to parties that promise to restore cultural and political power to the regions. Several of the more popular minor parties to arrive on the political scene in recent years – notably One Nation and Nick Xenophon – have gained higher support in the country than they have in the cities.

The rising minor party vote sends a signal to our major party politicians: Australians are not satisfied with politics as usual. Major parties seeking to increase their appeal should focus on what matters to voters: restoring trust and social cohesion.

Rebuilding trust will be a slow process. A period of leadership stability and policy delivery could go a long way. And improving the way we do our politics – reforming political donation laws and tightening regulation of lobbying and political entitlements – could help reduce the incidence of trust-sapping scandals and reassure the public that the system is working for them.

Politicians should also seek to dampen rather than inflame cultural differences. Politicians can lead by stressing the common ground between city and country and between communities with different backgrounds.

Failure to heed the warning will mean more elections where Australians unleash their displeasure at the ballot box.