Published at The Conversation, Wednesday 10 July

Compulsory superannuation was sold to Australians on the basis that it would make us better off.

But as the government prepares for an independent inquiry into retirement incomes, new Grattan Institute research finds that increasing compulsory contributions from 9.5% of wages to 12%, as has been legislated, would leave many Australian workers poorer over their entire lifetimes.

They would sacrifice a significantly increased share of their lifetime wage in exchange for little or no increase in their retirement income.

The typical worker would lose about A$30,000 over her or his lifetime.

Superannuation delivers higher incomes in retirement at the expense of lower incomes while working.

Yet the superannuation lobby usually presents only one side of the pact, urging an increase in compulsory super to get the higher retirement incomes while ignoring the income that workers have to forgo to get them.

Compulsory super contributions are paid by employers. But they appear to come out of funds the employers would otherwise have spent on wages.

This means increases in compulsory super come at the expense of wage increases – something that was acknowledged when compulsory super was set up (indeed, it was part of the reason it was set up) and has been acknowledged by advocates of higher contributions, including the former opposition leader Bill Shorten).

Grattan Institute calculations suggest that lifting compulsory super to 12% by 2025 will take up to A$20 billion a year from workers’ pockets. For most, the trade-off isn’t worth it.

The reality is that most Australians can already look forward to a better living standard in retirement than they had while working – even if they interrupt their careers to care for children. Workers with interrupted employment histories lose super in retirement, but get larger part-pensions.

The poorest Australians get a clear pay rise when they retire: the age pension is worth more than their after-tax income while working.

Other Grattan Institute research finds retirees are more comfortable financially than any other group of Australians and are much less likely to suffer financial stress than working-age Australians.

So what about Middle Australia?

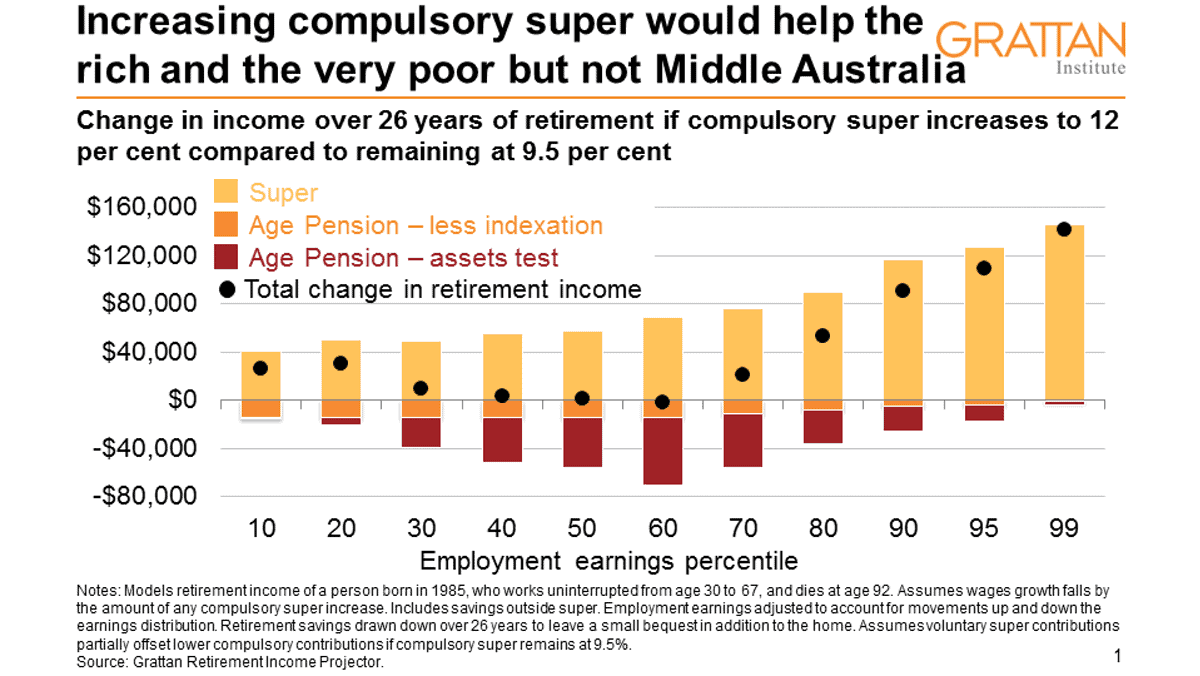

Despite the “magic” of compound returns, just about all of the extra income from a higher super balance at retirement would be offset by lower pension payments, due to the pension assets test.

It is always possible the pension rules will change, but it isn’t usually regarded as wise to assess proposals on the basis of changes that haven’t happened and aren’t being suggested.

Pension payments themselves would also be lower under a 12% superannuation regime. They are benchmarked to wages, which would be lower if employers have to put more into super.

The graph below shows that the big winners from higher compulsory super would be the wealthiest 20% of Australian earners, who would benefit from extra super tax breaks and would be unlikely to receive the age pension anyway.

Higher compulsory super redistributes income from the middle to the top. Middle earners would be no better off.

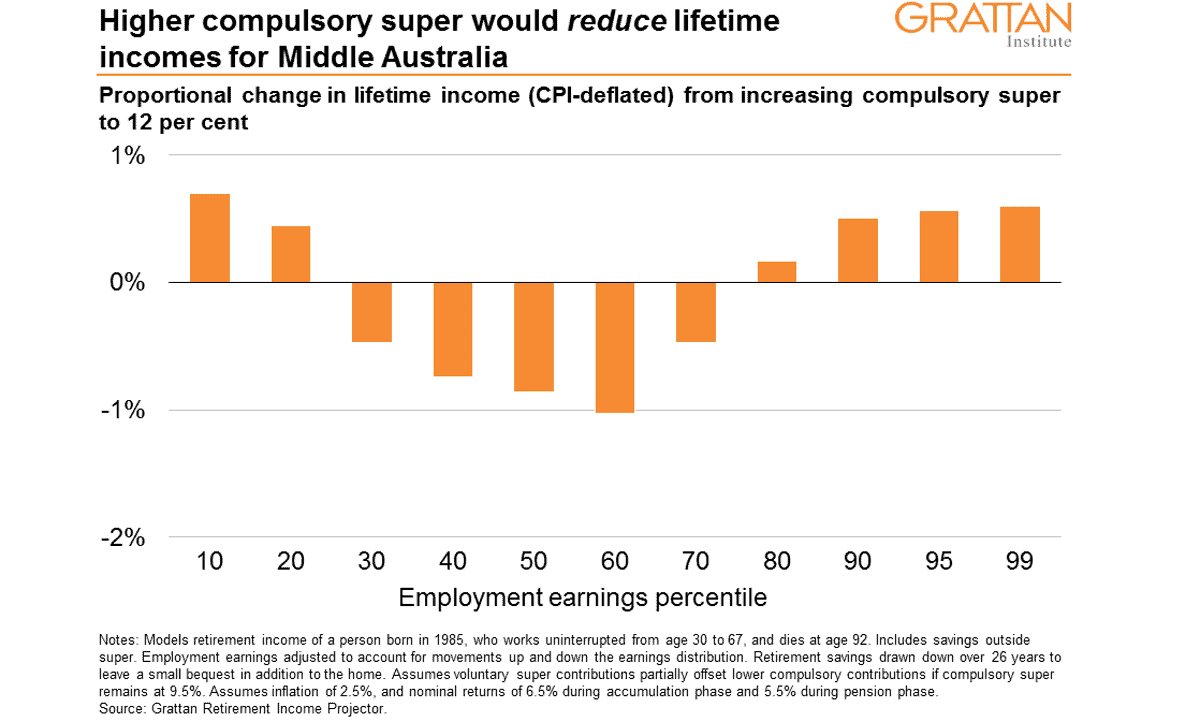

As higher compulsory super would leave Middle Australians no better off in retirement, but poorer while working, it follows that it would make them poorer over their entire lives.

How much poorer? We calculate that, after adjusting for inflation, the typical (median) 30-year-old Australian worker earning A$58,000 today would lose about 2.5% of wages each year and get less than a 1% boost to retirement income.

As a result, that person’s lifetime income would be almost 1% lower – about A$30,000 lower.

A post published on the Grattan Blog today gives more detail on the method we used to calculate the impact of higher compulsory super on lifetime incomes.

Higher compulsory super might be justified if it saved the budget money on the pension – because those savings could be used to compensate middle-income earners via lower taxes or more services.

But in fact, higher super would cost the budget.

Our modelling shows that lifting compulsory super to 12% of wages would cost taxpayers an extra A$2 billion to A$2.5 billion per year in super tax breaks, overwhelmingly directed at high-income earners.

Those extra super tax breaks would dwarf any budget savings on the age pension until about 2060 – by which time there would be 80 years of budget costs from compulsory super to pay back before the whole exercise saved the government money.

Here’s the bottom line, worth keeping in mind in the lead-up to the independent inquiry: it’s hard to think of a policy less in the interests of working Australians than more compulsory super.![]()