Published in Inside Story, 30 November 2020

Much of the public debate about retirement incomes rests on the assumption that the federal budget will struggle to keep financing an age pension if most Australians don’t self-fund their retirement via superannuation. The age pension, on this view, is best seen as a safety net for the poorest Australians.

This is the thinking that motivates a procession of Labor luminaries, from Paul Keating down, to call for the government to lift compulsory superannuation contributions to 12 or even 15 per cent of wages. It also drives assertions by the super lobby that you can’t have a “dignified” retirement unless you are self-funded. And it fuels the argument of Coalition backbenchers that super has failed because most younger Australians can still expect to receive at least some of the age pension in retirement.

The retirement income review, released last week, challenges all these assumptions. It shows that the age pension today, far from simply being a safety net, will remain an important source of retirement income for all but the wealthiest Australians, even if compulsory super rises. In other words, raising compulsory super to make most Australians “self-sufficient” in retirement is not just misguided, it is also destined to fail.

The review shows that most of today’s retirees rely on the age pension for the bulk of their income. It’s a big reason why most of them have more income in real terms now than they did twenty years ago, when they were of working age. And rather than living on the breadline, the review points out, these retirees have higher levels of financial satisfaction and are much less likely to suffer severe financial stress or poverty than younger Australians.

The pension’s role is unlikely to diminish much in coming years. The review expects nearly half of younger Australians today to receive half or more of their income from the age pension when they retire in three decades’ time, and a bit more than half if compulsory super doesn’t rise beyond 9.5 per cent. Either way, they’ll typically enjoy a better living standard in retirement than across their working lives.

Many supporters of super see this as a sign of failure. But the enduring importance of the age pension to the incomes of middle-income retirees is a sign of a healthy retirement system. This means-tested payment plays a crucial role in insuring Australians against many risks they face that might hurt their retirement.

Take the 1.3 million Australians currently out of work and therefore without an employer contributing to their super. What they forego in super contributions today is largely offset by a higher age pension in retirement. That’s also why workers who dipped into their super during the Covid-19 crisis will suffer a smaller hit to their overall retirement incomes — super plus pension — than is commonly portrayed. The review’s modelling shows median workers who withdrew $20,000 in super when they were thirty, then remained out of the workforce for two years and underemployed for another five, will see their retirement income fall from 87 per cent of their pre-retirement earnings to 82 per cent — still well above the 65 to 75 per cent “replacement rate” adopted by the review.

There’s endless talk about the need for superannuation products that better manage the risk that retirees will live longer than expected and exhaust their private savings. And super funds could certainly help retirees manage these risks better. But what’s often overlooked is that the age pension is already providing substantial “longevity risk” insurance for most Australians.

The pension also protects many (but not all) retirees from the risks of lower investment returns, since they will qualify for a larger part-pension if they have fewer assets. If investment returns are 0.5 per cent lower than we expect over the next sixty years, the review’s modelling shows the median worker aged thirty today will enjoy 85 per cent of his or her pre-retirement wage in retirement, rather than 88 per cent if returns don’t fall.

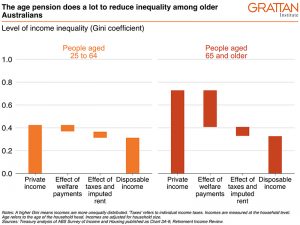

Together with the broader tax–transfer system, the age pension’s means test redistributes income towards low- and middle-income retirees, reducing income inequality in old age. Without it, income inequality among retirees would be far higher than among working Australians.

The age pension is also the one part of our retirement income system that is closing the gender gap in retirement incomes, since it redistributes income to women who, on average, have fewer retirement savings than men.

These features of our retirement income system should be celebrated. But it’s the age pension, rather than superannuation, that’s delivering them.

Even since the FitzGerald inquiry into national savings in 1993, super has been seen as a way of replacing the age pension for many, if not most, retirees by helping them to become “self sufficient.” But a closer look at the structure of the pension shows it’s unlikely to disappear anytime soon, no matter what happens to compulsory superannuation. And nor should we want it to.

The age pension needs to be adequate to help people with few other assets or little other income to avoid living in poverty. (At the current rate it achieves this for homeowners but not for renters.) Its means test should be set at a level that does not excessively discourage saving.

Given these realities, it’s inevitable that middle-income Australians will continue to receive at least some, and in many cases much, of the age pension over the course of their retirement. The only alternative would be to raise the compulsory super rate to such a level that the vast majority of Australians would save far more than necessary and be poorer during their working years.

The retirement income review makes this clear when it says that a key objective of the system is “to balance living standards across a person’s working life and retirement.” The review’s benchmark for an adequate retirement income is 65 to 75 per cent of pre-retirement earnings. Anything more gets the balance wrong, especially since it’s hard for workers to save less than the compulsory rate.

Our research at the Grattan Institute suggests that lifting compulsory super to 15 per cent or even 18 per cent — the level required to push many more people off the age pension — would mean that a retiree who had earned the median income would receive 92 per cent or 94 per cent of his or her pre-retirement earnings. The bottom 30 to 40 per cent of workers would be forced to save for a retirement income that exceeded their wage pre-retirement.

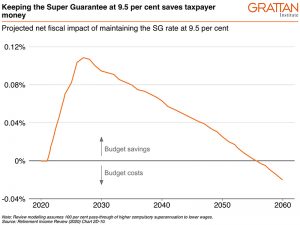

Whatever the benefits of super in reducing pension costs, higher compulsory super would hurt rather than help the federal budget for decades to come. Why? Because super comes with extraordinarily generous tax breaks.

The FitzGerald inquiry believed that the revenue lost because of compulsory super would never exceed 0.2 per cent of GDP and that the pension savings from compulsory super would outweigh super tax breaks by the early 2020s. Two decades later, though, Treasury estimated that the revenue forgone from tax breaks for compulsory super, once contributions were lifted from 9 per cent to 12 per cent (as was legislated to occur by 2018), would exceed the budget savings on the pension by 0.4 per cent of GDP a year.

Modelling for the recent review shows that lifting compulsory super from today’s 9.5 per cent to 12 per cent would cost taxpayers more in super tax breaks than they would save from spending on the age pension through until 2055. And even then, thirty-five years of accumulated debt — more than 2 per cent of GDP — would need to be paid back before taxpayers ended up ahead.

Of course, this arithmetic could change if the government curbed Australia’s overly generous superannuation tax breaks. But they would need to be cut dramatically — perhaps by $10 billion a year out of about $30 billion — before the budget would save real money much sooner than 2055. Given that the Turnbull government’s 2016 reforms to super tax breaks saved less than $1 billion a year, the prospect of any government making such drastic changes to super tax breaks appears remote.

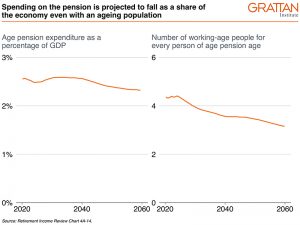

One last myth the retirement incomes review challenges is the belief that the age pension as financially unsustainable. As the review’s projections show, the government’s spending on the pension — stable over the past twenty years — is likely to fall a little, as a share of the economy, over the next forty years.

In 2001, the age pension cost 2.2 per cent of GDP. It’s now about 2.5 per cent, and the review projects that to fall to 2.3 per cent by 2060. If compulsory super stays at its current level of 9.5 per cent rather than rising to 12 per cent, the review projects that the pension will cost 2.4 per cent of GDP in 2060.

There’s no doubt that compulsory super has cut pension costs, but arguably the bigger reason why Australia’s age pension is fiscally sustainable is its unique design. It’s more tightly means-tested than pensions elsewhere, and the maximum rate is the same for everyone, set just above the poverty line, rather than a proportion of workers’ pre-retirement earnings.

And there’s little chance of any political constituency calling for wholesale cuts to the pension. A growing proportion of Australia’s voters are aged fifty-five and older, and between 1995 and 2015, the proportion of eligible voters in that group grew from 27 per cent to 34 per cent. But they wield even more power than that figure suggests: because younger Australians are less likely to enrol to vote, people aged fifty-five or more now make up 38 per cent of enrolled voters. Cuts to the pension would an incredibly tough sell for any party.

The biggest risk to the pension comes from thinking that superannuation should replace it. It distracts us from fixing the big holes in the retirement system that reflect shortcomings in the publicly funded social safety net rather than in the superannuation system.

Most Australians are comfortable in retirement, but the system is failing too many poorer people, especially in three groups: low-income women, those forced into early retirement, and retirees who rent. The best predictor of poverty in retirement today is whether retirees own their own homes. And that problem will only get worse, because young Australians on lower incomes are less likely to own homes than in the past. Rates of homelessness are already on the rise among older Australians, including older women.

Raising Commonwealth Rent Assistance by at least 40 per cent should be the number one priority to reduce poverty in retirement, although the review shows that a much bigger increase may be needed. Other parts of the social safety net also desperately need repair. The permanent rate of JobSeeker should be substantially increased. And access to the disability support pension, which was tightened in 2012, should be reviewed.

These are the real challenges in ensuring our retirement income system lives up to its promises to all Australians. But fixing them starts with acknowledging that the age pension is here to stay — and that’s a good thing.