Published by Inside Story, Friday 12 January

There’s an important insight amid the wreckage of the Turnbull government’s claim that tightening tax breaks for housing investors would crash house prices. The Treasury advice released this week confirms that reforms to negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount will not “take a sledgehammer” to the housing market, as the prime minister once suggested. But Treasury’s advice shows that they will not make housing much more affordable either.

The debate over negative gearing illustrates a broader problem ignored by many affordable housing advocates. While negative gearing and a number of other housing tax reforms are definitely worth pursuing, they alone won’t solve our housing affordability crisis.

Treasury’s advice confirms previous Grattan Institute research showing that abolishing negative gearing and halving the capital gains tax discount to 25 per cent would leave house prices roughly 2 per cent lower than otherwise, favouring would-be homeowners over investors.

Of course, the price changes wouldn’t be uniform across Australia. Prices would probably fall a bit more for cheaper housing, since tax breaks have channelled investors into low-value homes that pay less tax under state land tax thresholds. But even in apartment markets dominated by investors, the maximum rational price impact shouldn’t exceed 3 to 4 per cent. In other markets the impact will be practically zero. And price falls could be larger in markets where the tax breaks have encouraged highly leveraged investors to chase higher capital gains, or where investors place more value on the tax benefits of negative gearing than they’re really worth.

And so the dominant rationale for reforming negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount remains their economic and budgetary benefits. The current tax arrangements distort investment decisions and make housing markets more volatile. Abolishing negative gearing and halving the capital gains tax discount would boost the federal budget’s bottom line by around $5 billion a year. battle

Extending state land taxes to owner-occupied housing would have a bigger impact on prices while also helping state budgets to the tune of $7 billion nationally. If the funds were used to abolish more economically costly taxes — such as taxes on insurance — they would give a big boost to the economy. Again, though, the impact on house prices is modest: they would be around 3 per cent lower than otherwise.

State governments should also abolish stamp duties on property, and replace them with a general property tax, as the ACT government is doing at the moment. But replacing one tax on property with another collecting the same revenue won’t have a big impact on house prices. The real justification is that it would help workers to take a better job that’s only accessible by moving house, and so improve economic growth. It’s a big prize: a national shift from stamp duties to broad-based property taxes could leave Australians up to $17 billion a year better off.

Including the family home in the age pension assets test would also make only a small difference to housing affordability because few seniors would choose to downsize. Research shows that downsizing is primarily motivated by lifestyle preferences and relationship changes. Surveys suggest that no more than 15 per cent of downsizers are motivated by financial gain, with only 1 per cent nominating the impact on their pension as their main reason for not downsizing.

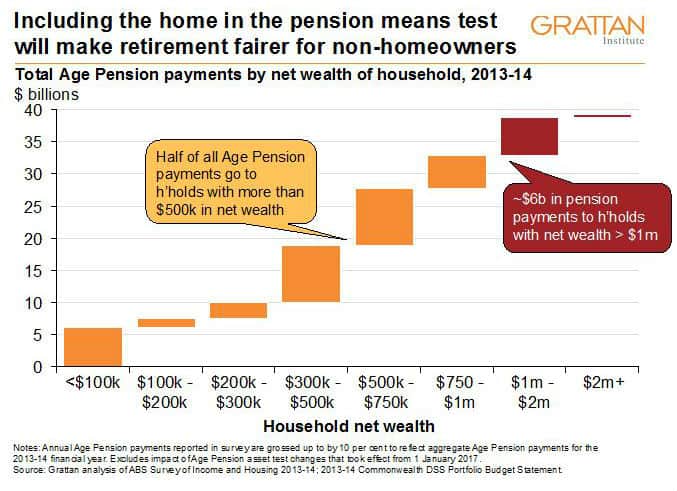

But reforming the pension means test would still make the retirement incomes system fairer and contribute to budget repair. Half of the government’s spending on age pensions goes to people with more than $500,000 in assets.

If the value of homes above $500,000 was included in the age pension assets test — and the asset-free area of homeowners was raised to the level that currently applies to non-homeowners — the Commonwealth budget balance could improve by between $1 and $2 billion a year.

And no senior would be forced to move. Asset-rich, income-poor retirees could continue to receive a full pension by borrowing against the value of the home until the house is sold. If well designed, this scheme would have almost no effect on retirees — instead, it would primarily reduce inheritances.

All these reforms are worth doing. Each would produce big budgetary and economic benefits. But even if federal and state governments adopted them all they would have only a modest impact on Australia’s $7 trillion housing market. House prices would be unlikely to fall by more than 10 per cent from where they would be otherwise — small beer compared to the tripling of house prices over the past three decades. And governments have little control over two of the biggest drivers of rising housing demand: higher incomes and record-low global interest rates.

If governments are serious about affordability, then a boost in the supply of housing is also needed, even if it will take time.

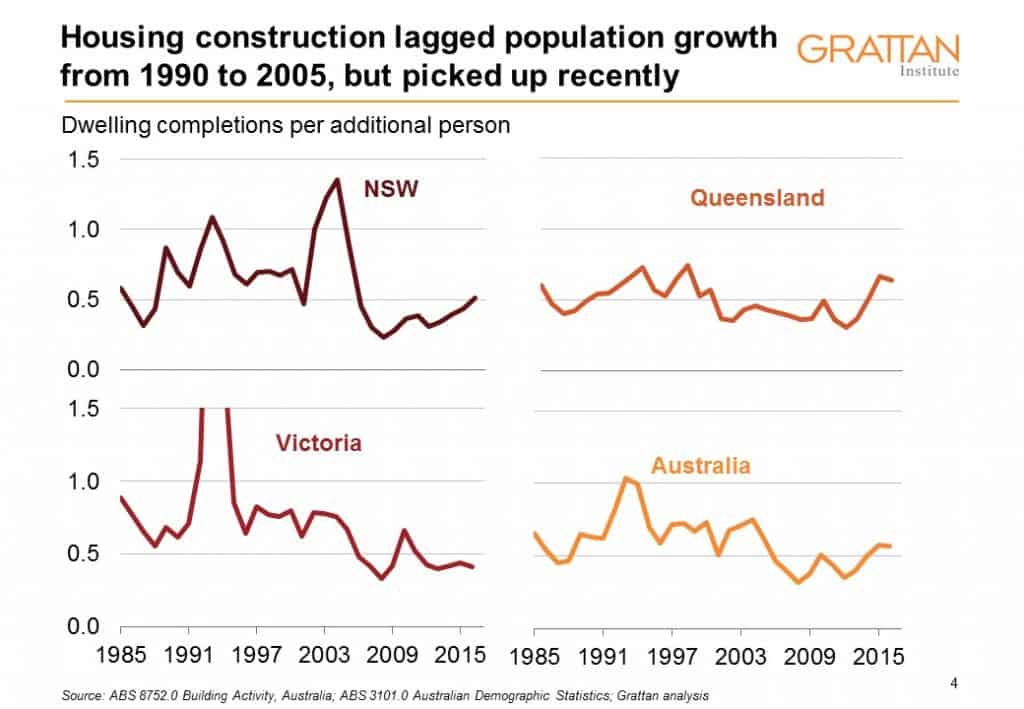

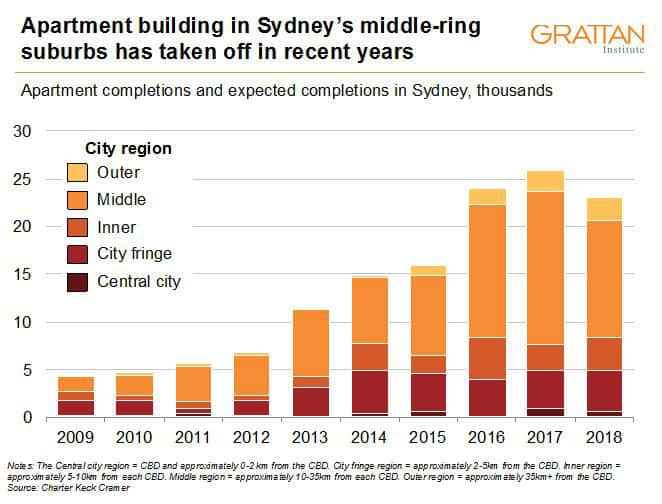

Until recently, the supply of new homes wasn’t keeping pace with demand. Planning rules and practices made it reasonably easy to build apartments in the CBD and to develop new housing estates on the city fringe. But they made it relatively difficult to redevelop the inner and middle-ring suburbs of major cities, where many people would prefer to live because they would have better access to jobs.

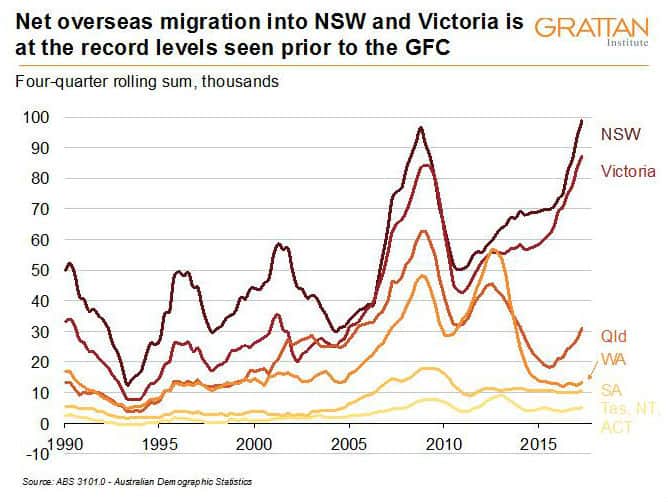

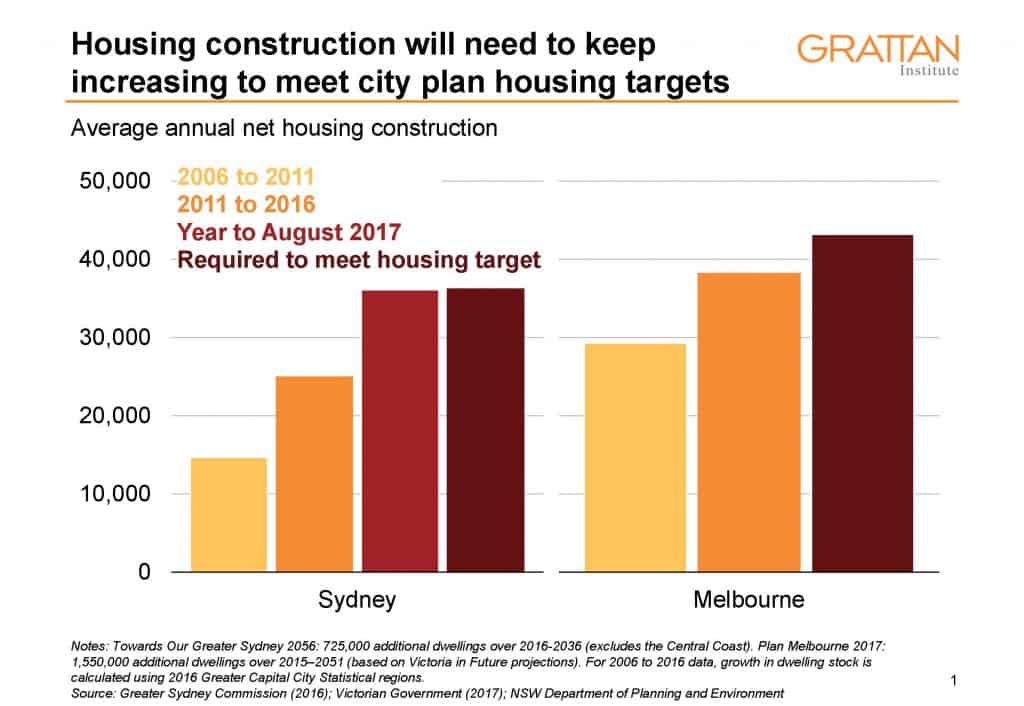

Development in middle suburbs has increased in recent years, especially in Sydney. But today’s record level of housing construction is less impressive than it seems because population growth into Sydney and Melbourne has been so strong.

In fact, development at today’s record rates is the bare minimum needed to meet both cities’ housing supply targets over the next forty years.

The best evidence suggests that boosting housing supply will improve affordability, albeit only slowly. Even at current record rates, new housing construction increases the stock of dwellings by only about 2 per cent each year. But, on one estimate, adding an additional 10,000 homes a year above current rates of housing construction for the next decade could see national house prices almost 20 per cent lower than they would be otherwise.

Within living memory, Australian housing costs were manageable, and people of all ages and incomes had a reasonable chance to own a home close to jobs. Now, home ownership rates are falling among the young and the poor. Owning a home increasingly depends on who your parents are, a big change from thirty-five years ago, when home ownership rates were similar for all income groups.

Perhaps the most frustrating aspect of the Australian housing affordability debate is the tendency to focus on any one policy lever to the exclusion of all others. The federal government insists that supply alone will make housing more affordable. Many affordable housing advocates argue the opposite. As the battle lines sharpen over whether demand or supply is the right way to tackle housing affordability, we risk getting bogged down without achieving anything. And all the while housing will become even less affordable for younger generations.

There is no silver bullet. Both strong demand and weak supply have pushed house prices higher. Improving affordability will therefore require policies affecting both demand and supply. Tax reforms that reducing housing demand could reduce prices somewhat. In the long term, though, boosting the supply of housing will have the biggest impact on affordability.

Published by

Published by