The current controversy about who should declare pandemics and introduce public health restrictions is a nice illustration of one of the dilemmas of public policy — how to manage choice when both options before the decision maker are good, but both also have downsides.

In the pandemic declaration case, there is a clear binary choice: either the decision is formally vested in the Chief Health Officer — as is the case now in Victoria and also Queensland — or it should be vested in a politician, i.e. the Premier or the Minister for Health, as is the case in NSW. There are precedents and good reasons for either choice, and benefits and costs with either choice.

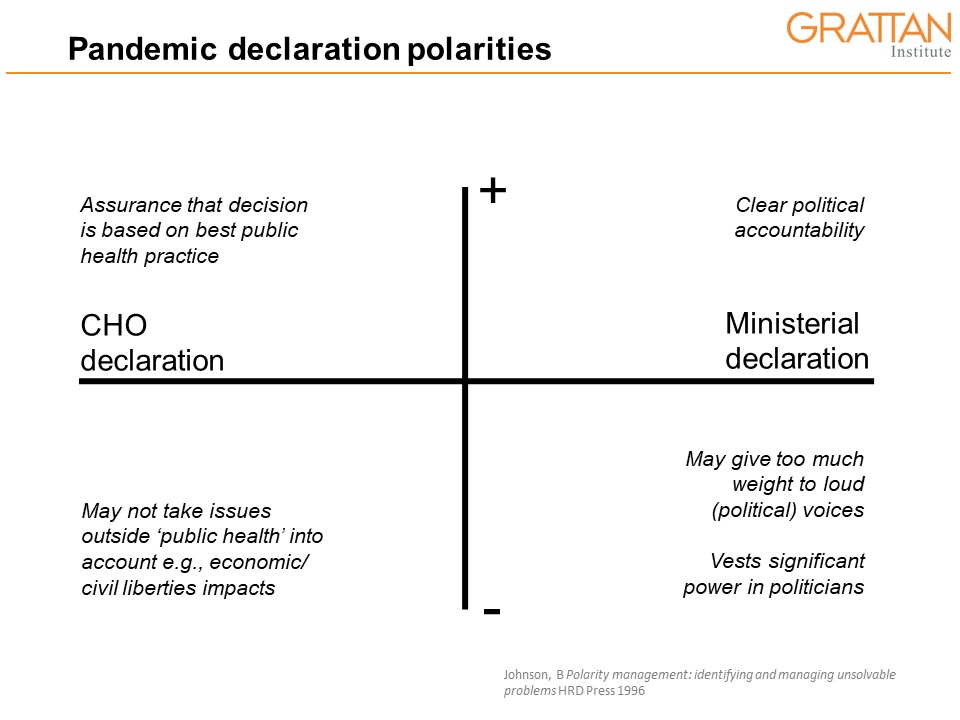

In these circumstances I find a technique known as polarity management useful.

In essence, options are analysed in terms of a plane — with one polarity (CHO declaration) at one end of the horizontal axis, and the other polarity, ministerial declaration, at the other end. The vertical axis is about the positives and negatives of each choice. In the four quadrants created by the two axes one can list the various strengths and weaknesses, as shown here.

Landing on either of the two choices inevitably brings the negatives as well as the positives of that choice. Good policy requires thinking about how you minimise the negatives of the choice you land on, and how you might get some of the benefits of the positives of the alternative choice. Conceptually you start in one of the two top quadrants, move down to the associated negative quadrant, and then move up to the alternative positive quadrant.

Let’s assume you decide that ministerial declaration is the right answer. How do you avoid giving too much weight to loud political voices (an associated negative)? And how do you ensure that you are actually going to be following the best public health advice?

Or alternatively, let’s assume that CHO declaration is the right answer. How do you ensure that the CHO considers the broader economic and civil liberties issues associated with restrictions?

While the contentious Bill before the Victorian Parliament proposes ministerial declaration, it also seeks to mitigate some of the downsides of this approach by drawing on some of the benefits of a CHO declaration, by requiring that the CHO’s advice be sought, and that it be published.

The debate might be more productive if it moves away from focusing only on the perceived negatives and starts to focus on whether the Bill’s provisions are enough to get the alternative positives, and how some of the perceived negatives might be mitigated.

While you’re here…

Grattan Institute is an independent not-for-profit think tank. We don’t take money from political parties or vested interests. Yet we believe in free access to information. All our research is available online, so that more people can benefit from our work.

Which is why we rely on donations from readers like you, so that we can continue our nation-changing research without fear or favour. Your support enables Grattan to improve the lives of all Australians.

Donate now.

Danielle Wood – CEO