Why the infrastructure splurge is a bad deal for taxpayers

by Marion Terrill

In the seat-by-seat slugfest that is the federal election, transport infrastructure is once again at the forefront. Small, hyper-local projects are a favourite of both major parties this time around. That’s even though small local projects, such as roundabouts and carparks, simply aren’t the job of the federal government, and in practice often go badly.

A better deal for taxpayers would be for whichever party wins government on Saturday to halt this spending on small local infrastructure, and focus instead on nationally significant projects that have been properly assessed by Infrastructure Australia.

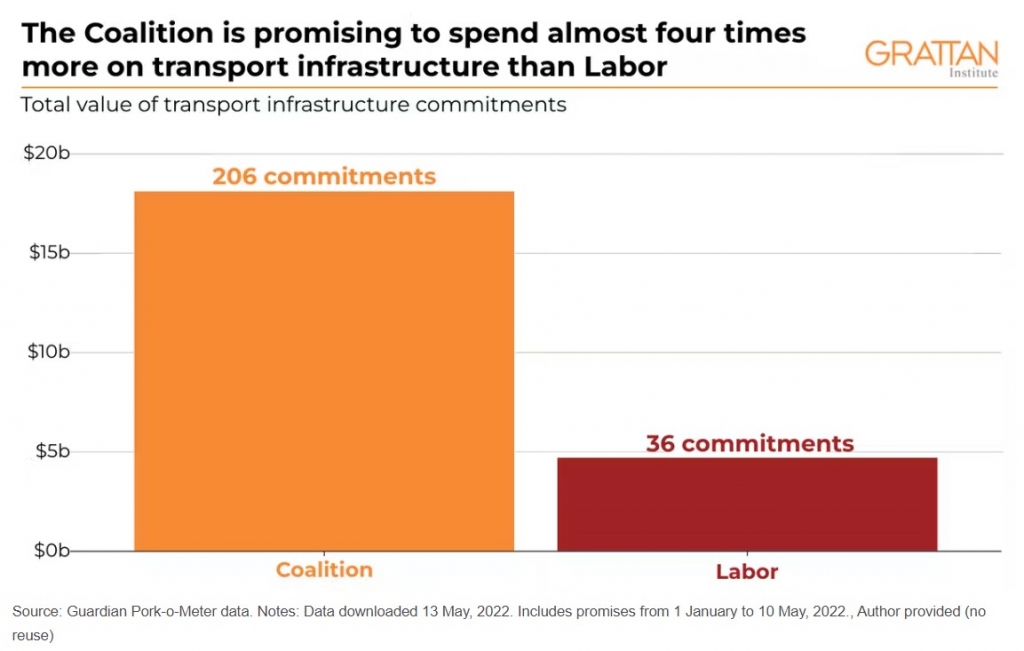

There’s a big difference in what the parties are promising. The Coalition has committed an exuberant $18.1 billion worth; Labor a much more restrained $4.7 billion worth[1]. In both cases, these transport promises are a pale shadow of the 2019 campaign, when the Coalition promised $42 billion worth, and Labor an eyewatering $49 billion.

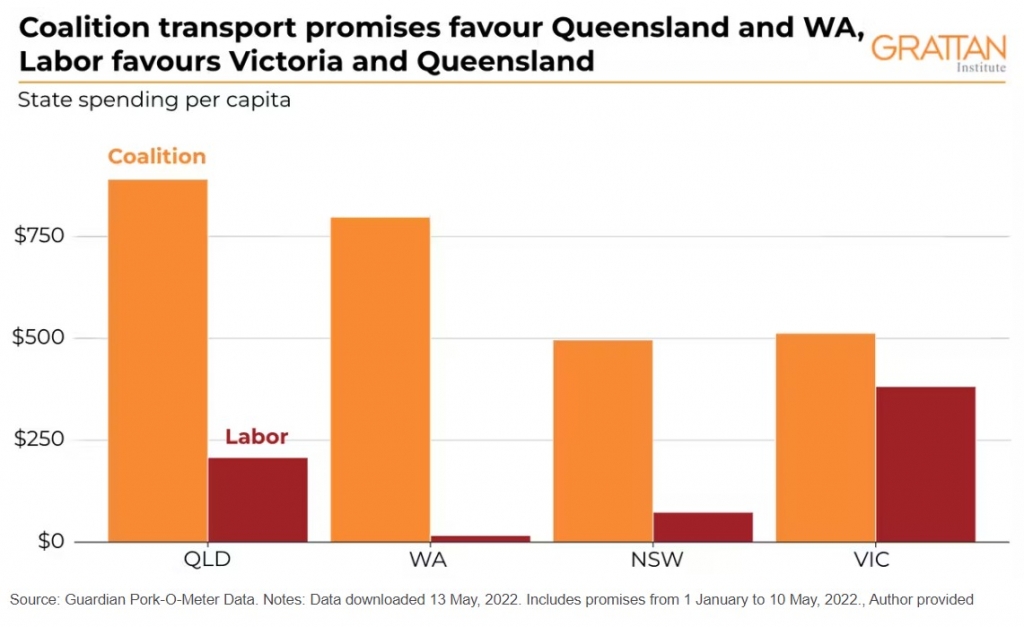

The Coalition is sticking with the dominant strategy of the past 15 years, which is promising more funding to Queensland – the state where elections tend to be won and lost.

It has promised nearly $900 per Queenslander in transport funding, compared with about $500 for each person in New South Wales and Victoria. Labor hasn’t overlooked Queensland either; although its promises favour Victoria, at close to $400 per person, Queenslanders are next in line, with about $200 worth of transport spending each.

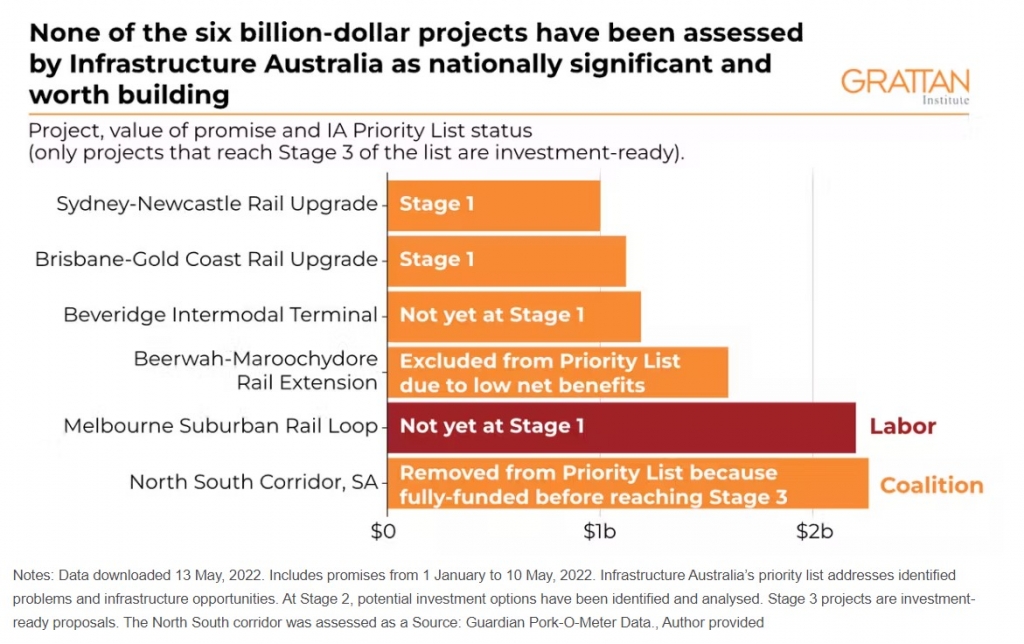

Billion-dollar projects are much less prevalent than they were last election, with just six of them promised so far (five by the Coalition, one by Labor).

Of the six, none has been assessed by Infrastructure Australia as nationally significant and worth building. Two have yet to achieve the first stage of assessment; two are early in the process of being assessed; one didn’t make it onto the list because its costs would outweigh its benefits, and one has been removed from the list because it has been fully funded – although that appears to have happened before a full appraisal was completed.

And that’s even with the newly watered-down requirement for Infrastructure Australia scrutiny: since January 1 2021, only projects that require more than $250 million in federal funding are supposed to be scrutinised, a lax threshold compared with the $100 million threshold that used to apply.

It’s prudent for potential future governments to step back from the megaproject binge of recent years. The engineering construction sector has been raising red flags for years about its capacity to deliver the existing pipeline of projects, never mind adding to it.

Even before the pandemic, employment in the sector had surged by 50%, and supply chain disruptions have made it slower, more difficult, and more expensive to source materials. What’s more, the slowing of population growth has dampened the rationale for big new projects, and strengthened the case to maintain and upgrade assets. Even so, both parties are promising more for new construction than upgrades.

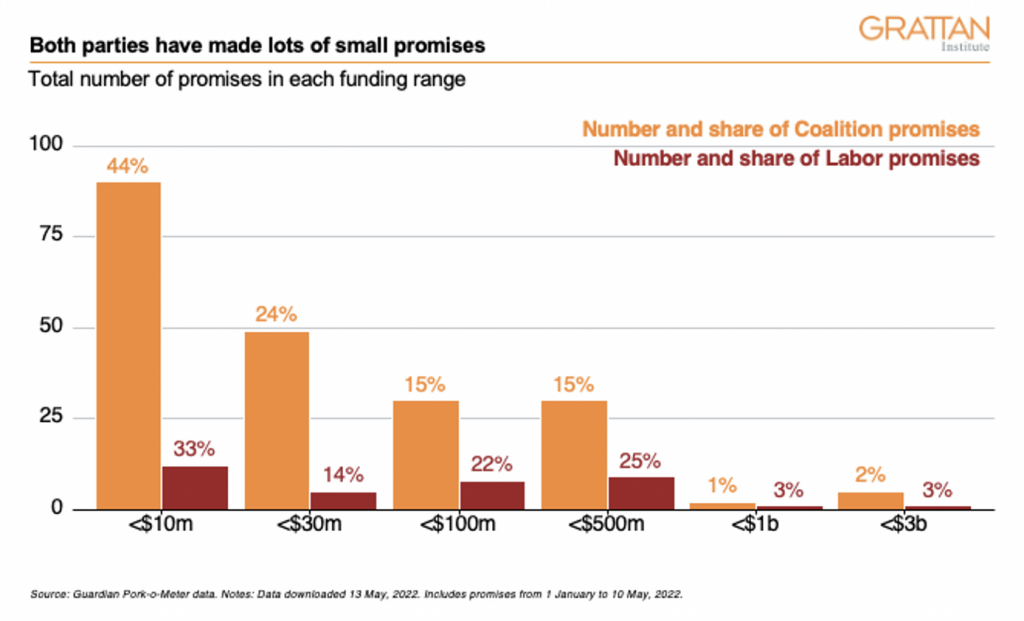

In fact, the parties have gone hard for tiny projects. Two-thirds of the promised spend of the Coalition, and nearly half of Labor’s, is for projects valued at $30 million or less. For the Coalition, these include commuter car park upgrades at Panania in the electorate of Banks (NSW), Hampton in Goldstein (Victoria), Woy Woy in Robertson (NSW), and Kananook in Dunckley (Victoria). For Labor, they include upgrading the Mornington roundabout in Franklin (Tasmania), and several roundabout upgrades in Perth.

These very small, hyper-local projects may be important to the local community, and popular, but there’s no roundabout or car park in the land that’s nationally significant.

When the federal government encroaches on the turf of state and local government like this, it often goes badly. The commuter car parks that were cancelled in 2021 and 2022 show what can go wrong when a federal government operates outside its proper sphere: projects had to be cancelled because there were no feasible design options, feasible sites, or because the railway station was being merged with another.

Political parties make little secret of the fact they use transport spending to win votes. Indeed, given transport spending seems to be electorally popular, politicians may ask what’s wrong with focusing investment on electorally important states and seats? Well, there are three problems.

First, the quality of the projects promised in the heat of election campaigns is poor, with none of the billion-dollar-plus projects this time around having been positively assessed by Infrastructure Australia.

Second, government decisions should be made in the public interest, and those making the decisions should not have a private interest – including seeking private political advantage, with public funds.

And third, much of the promised spending lies outside the federal government’s proper role of funding nationally significant infrastructure, focusing instead on small hyper-local projects that are the remit of state and local governments.

Voters should demand better. Whichever party wins the 2022 federal election should strengthen the transport spending guardrails.

The government, whether Coalition or Labor, should require a minister, before approving funding, to consider and publish Infrastructure Australia’s assessment of a project, including the business case, cost/benefit analysis, and ranking on national significance grounds.

And the next federal government should also stick to its job: no more roundabouts or car parks, just nationally significant infrastructure that’s been assessed as worth building.

Footnotes

- As at Tuesday 10 May 2022

While you’re here…

Grattan Institute is an independent not-for-profit think tank. We don’t take money from political parties or vested interests. Yet we believe in free access to information. All our research is available online, so that more people can benefit from our work.

Which is why we rely on donations from readers like you, so that we can continue our nation-changing research without fear or favour. Your support enables Grattan to improve the lives of all Australians.

Donate now.

Danielle Wood – CEO