Overview

Gambling is everywhere: on our screens, in our pubs and clubs, and available anytime at our fingertips. But gambling products are not like other forms of entertainment – it is all too easy to lose too much.

Australia has taken a lax approach to gambling, and it shows. We have the highest gambling losses in the world. Pokies and online betting are particularly addictive and harmful, leading to serious harm for hundreds of thousands of Australians.

Pokies are more common in our suburbs than post boxes, ATMs, or public toilets. They are concentrated in our most disadvantaged communities. And they are particularly prevalent in NSW, which has almost as many pokies as the rest of Australia combined.

Meanwhile, online betting has surged, particularly among young men, spurred by a barrage of gambling advertising.

People who gamble, their families, and the broader community pay the price. Gambling can lead to financial and mental distress, relationship breakdown, family violence, and suicide.

How has it come to this? Gambling is big business, and the industry has repeatedly used its political power to thwart efforts to better protect the public. Gambling companies and peak bodies apply pressure to our politicians through every avenue to protect their profits.

Australia must get serious about preventing gambling harm and implement a package of reforms to make gambling less pervasive and safer.

Gambling normalisation starts young, and advertising is a major culprit. The federal government should ban all gambling advertising and inducements. That would go a long way to reducing Australians’ excessive exposure to gambling.

We also need a ‘seatbelt’ for the most dangerous gambling products, to stop catastrophic losses when people lose control. No one should lose their house, or their life, on the pokies.

Mandatory pre-commitment with maximum loss limits would ensure gamblers no longer lose more than they can afford. The federal government should establish a national pre-commitment system for online gambling, and state governments should roll out state-wide pre-commitment schemes for pokies.

In parallel, the federal government should investigate the feasibility of a universal pre-commitment system with maximum loss limits.

Governments should also improve support services to help those suffering harm now.

The gambling industry will push back on these reforms by denying the problems and stoking community fears. But this report shows that their trumped-up claims don’t withstand scrutiny. Federal and state governments should brave the vested interests and work together in the interests of all Australians to make gambling a safer, better bet.

Recommendations

Reduce people’s exposure to gambling

- Ban all gambling advertising and inducements.

- Reduce pokies numbers in each state over time.

- Add a gambling warning label to games that include gambling-like features, such as loot boxes and social casinos.

Roll out mandatory pre-commitment with maximum

loss limits

- Establish a national mandatory pre-commitment system for all online gambling, with daily, monthly, and annual limits on losses.

- In each state, introduce a state-wide mandatory pre-commitment scheme for pokies, with daily, monthly, and annual limits on losses.

- Investigate the feasibility of a single universal mandatory pre-commitment system across all forms of gambling.

Improve gambling support services

- Make treatment and support services a responsibility of health ministers, and commission a national review of services.

- Invest in any necessary service improvements and research gaps.

1 Gambling is Australia’s blind spot

Australia has let the gambling industry run wild. We were one of the first countries to deregulate gaming, and we’re still dealing with the consequences. Gambling is everywhere: on our screens, in our pubs and clubs, and available anytime at our fingertips.

Many people enjoy gambling without suffering harm. But it is all too easy to lose too much: these products have features that keep people coming back even when they are at risk of harm. That’s why gambling is strictly controlled in a number of countries.

Australia has taken a lax approach to regulating gambling, and it shows. We have the highest losses in the world. People who gamble, their families, and the broader community pay the price in their finances, health, and wellbeing.

1.1 Australia has the highest losses in the world

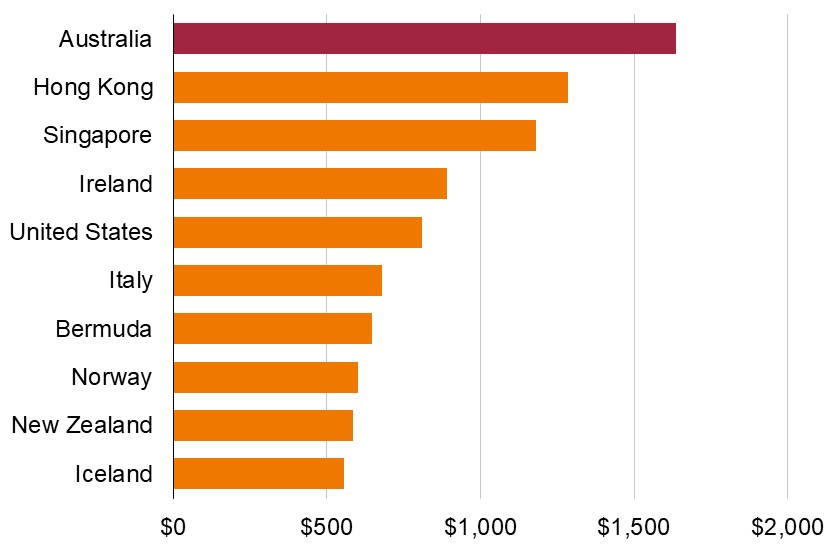

Australia has the highest per-capita gambling losses in the world. Our average annual losses per adult ($1,635) far exceed the average in similar countries such as the US ($809) and New Zealand ($584) (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: Australia leads the world in gambling losses

Gambling losses per adult in 2022, Australian dollars

Collectively, Australians lost $24 billion gambling in 2020-21 (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2: Australians lose $24 billion a year gambling, mostly on pokies and betting

Total losses by gambling type, Australia, 2020-21

1.2 Gambling is everywhere, addictive, and harmful

Gambling causes harm for too many Australians.

Gambling encompasses a range of activities where people stake money on an uncertain outcome, including lotteries, scratchies, pokies,1 betting,2 and casino games. About one in three Australians gamble regularly.3

This report focuses on pokies and betting, the most damaging forms of gambling in Australia today.4 Together, pokies and betting account for three-quarters of total gambling losses. About 1.2 million Australians use pokies, and 1.6 million Australians place a bet, in a typical month.5

Pokies and betting are everywhere; they’re addictive; and they’re harmful.

1.2.1 Gambling is everywhere in Australia, unlike the rest of the world

Pokies are in our suburban pubs and clubs, and betting is constantly available at our fingertips. And a flood of advertising, even in the most obviously inappropriate places,6 continually prompts us to gamble.

Pokies ‘basically on every corner’7

Australia had one electronic gaming machine for every 131 people in 2019 – more than almost any other country. The only countries with more were Japan, and casino tourism destinations, such as Macao.8

Not only do we have more gaming machines than most other countries, but our machines are also more damaging. Most of Australia’s

gaming machines are high-intensity poker machines (‘pokies’), which have high stakes and a fast rate of play.9 The expected loss on the highest-intensity machines, used at their maximum rate, is about $1,200 an hour for pokies in NSW.10

In other countries, high-impact, high-loss ‘Australian-style’ machines are typically confined to casinos.11 But in Australia, they are pockmarked across our suburbs and towns, increasing the risk of harm.

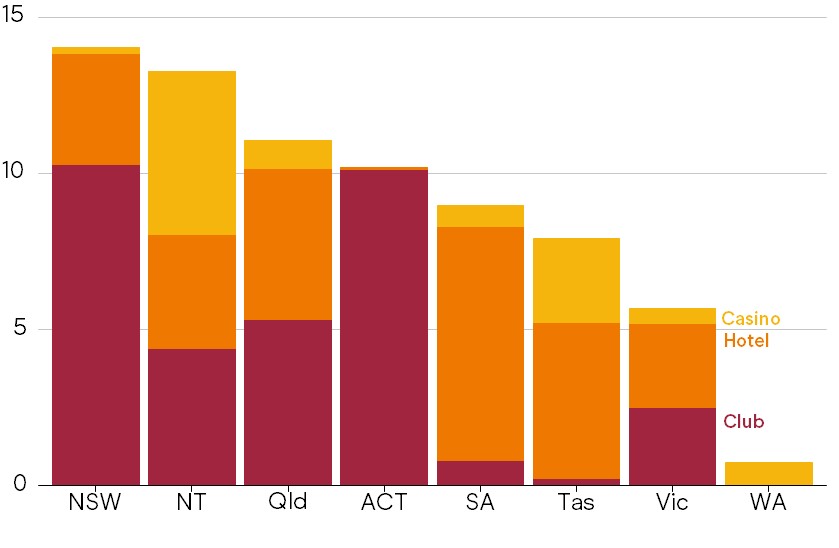

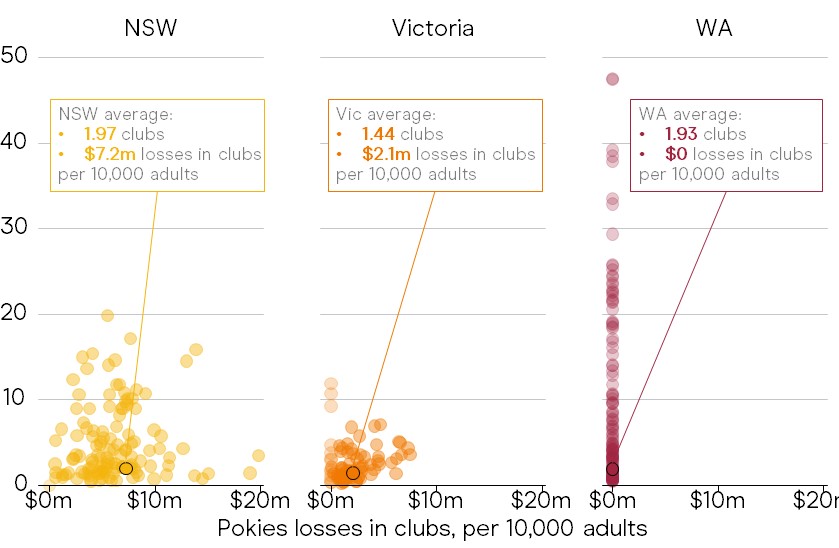

About 93 per cent of Australia’s 185,000 pokies are outside casinos.12 Suburban pokies are more common than ATMs,13 post boxes,14 or public toilets.15 Pokies are particularly prevalent in NSW (Figure 1.3). There are about 88,000 machines in NSW, or one for every 75 adults.16 NSW residents lost $1,288 per adult on pokies in 2023, double the average of the other states.17

Figure 1.3: NSW has the most pokies per person, and WA the fewest

Number of pokies per thousand adults, 30 June 2021

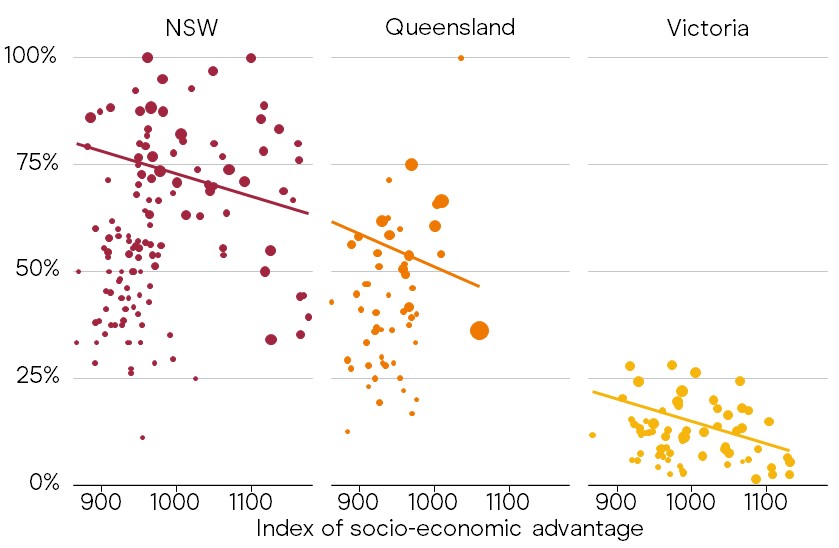

In many communities in NSW, particularly poorer communities, it’s difficult to find a venue that doesn’t have pokies (Figure 1.4). More than half of NSW’s pubs and clubs have pokies.

People who live close to pokies venues are more likely to gamble, and to gamble more often.18 Travel costs are lower, and, because pokies venues often host other events and activities,19 people are incidentally exposed to pokies while going about their lives. This can make it harder to avoid temptation.20

Betting at your fingertips and an inescapable ‘torrent of advertising’21

Betting – and betting advertising – are also widely accessible. Online betting is available anywhere, anytime: most people who regularly place bets online do so using a mobile or smartphone.22

Overall losses on betting have grown from $3.6 billion in 2008-09 to $5.8 billion in 2020-21.23 And online betting has surged, now accounting for about 85 per cent of total betting losses.24 The average Australian’s betting loss is more than double that of the average UK or US resident.25

Figure 1.4: In some communities, particularly poorer communities, it’s difficult to find venues without pokies

Proportion of pubs and clubs in local government area that have pokies

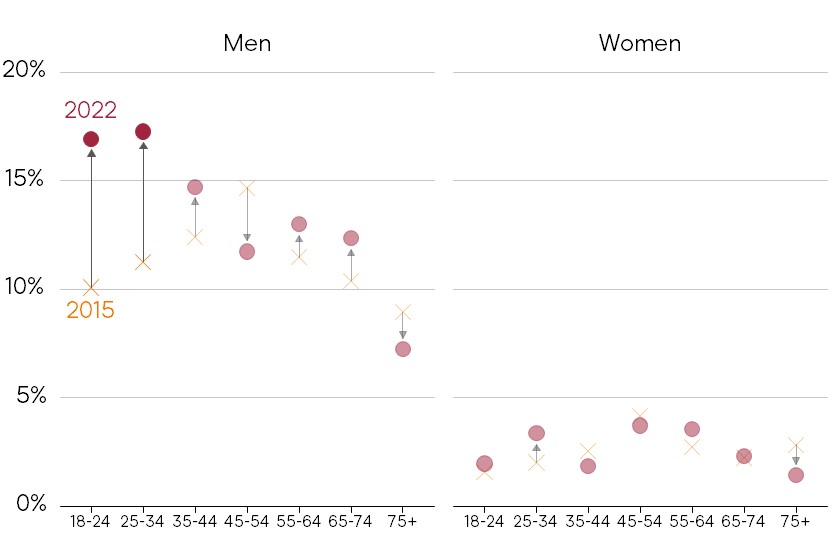

About 8 per cent of Australian adults placed a bet at least once a month in 2022. This average hides a stark gender divide: 14 per cent of men bet regularly, compared with just 3 per cent of women. Young men, in particular, have led the recent growth (Figure 1.5). Betting

is increasingly embedded in male social environments, reinforced by masculine norms of competitiveness and risk-taking.26

A barrage of gambling advertising spurs these trends, normalising gambling, inducing more spending, and triggering urges for people at risk.27 More than 1 million gambling ads aired on free-to-air TV and metropolitan radio in 2022-23.28 Online gambling companies are responsible for 64 per cent of total gambling advertising spending.

The 2023 Murphy Inquiry29 – a federal parliamentary inquiry into online gambling harm that reached multi-partisan consensus on all

31 recommendations – recommended ending the barrage of gambling advertising with a total ban.30

Figure 1.5: Young men have led the rise in betting

Proportion of age group that placed a bet in a regular month, 2022

Gambling advertising is particularly prominent around sport. As well as direct broadcast advertising,31 betting companies sponsor stadiums32 and teams,33 meaning their logos are visible throughout the game.

Most major sporting codes have ‘partnerships’ with online betting companies and receive a cut of the money bet on their games – so they have financial incentives to promote gambling among fans.34 Official apps display the odds for every game alongside the score.35

Betting companies also use online advertising,36 direct marketing, and inducements37 to entice gamblers, including those who are vulnerable to gambling harm (or, from the companies’ perspective, lucrative VIPs).38

The pervasiveness of gambling is no accident

The pervasiveness of gambling is no accident: it’s the result of decades of policy choices that have allowed the gambling industry, and its associated harm, to proliferate.

Australian governments were some of the first in the world to deregulate gaming.39 The NSW Government legalised pokies in the community in 1956; few other countries (or states) followed suit

until the 1990s.40 Even today, only a small number of countries allow high-intensity pokies outside of dedicated gambling venues (such as casinos).41 However, in Australia, only WA limits access to gaming machines in this way.

Australian regulations are well behind international best practice in other areas too. Several European countries have introduced

mandatory limits to reduce catastrophic harm (Appendix A), and others have banned or heavily restricted gambling advertising.42

The main reason Australia’s regulations are so weak is the influence of the gambling industry. Past reform efforts have been killed by highly organised, well-funded industry campaigns.

1.2.2 Gambling is addictive

The pervasiveness of pokies and betting is particularly dangerous because these products are not like ordinary consumer products.43

They can be harmfully addictive, and consumers are vulnerable to misunderstanding the product.44

The wiring of our brains makes us vulnerable to gambling harm. We use a range of cognitive heuristics that make it hard for us to make ‘rational’ gambling choices: for example, we often incorrectly believe that we can predict or control completely random events.45

The unpredictable size and pattern of many gambling wins and losses continually activates the brain’s reward system, reinforcing the behaviour.46 And quitting gambling activates brain regions related to subjective pain, anxiety, and conflict.47

Designers and manufacturers of all sorts of products seek to maximise revenue by making their products more attractive. But, in the case of some gambling products, this process has adverse consequences, with product design aggravating addictiveness to maximise losses.48

For example, over time, gaming machines have evolved from simple mechanical machines to advanced machines with complex payoff structures, audiovisual elements, and playing styles. Contemporary gaming machines have much greater potential for addiction and losses than their primitive forebears.49

Pokies’ audiovisual features, variable payouts, near misses, and losses that appear to be wins50 all provide regular dopamine hits and hijack the brain’s core decision-making processes.51 Some people find it difficult to walk away from pokies when they are ‘in the zone’, losing track of time and reality, and feeling that they are in a trance.52

Online betting products also have high potential for addiction and harm. Online gambling is accessible, immersive, and enables seamless, high- speed spending.53 Online betting products increasingly share some of pokies’ design characteristics, such as short payout intervals and high betting frequency, large-but-improbable jackpots with complex bets, and perceived ‘near misses’.54

These features make it difficult for people to regulate their gambling. Many people have difficulty controlling their gambling and don’t remember their wins or losses.55 In one survey, about a quarter of Australian households who reported that they spend money on pokies or betting said they were net winners – figures which are inconsistent with overall losses.56

For some, these problems develop into a clinical gambling addiction,57 characterised by differences in brain structure58 that lead to a loss of control of gambling spending and a significant risk of harm.59 Gambling addiction is recognised by the World Health Organization alongside alcohol and drug addiction.60 People with gambling addiction have similar brain activation and behavioural changes to people dependent on alcohol, nicotine, or cocaine.61

1.2.3 Gambling causes harm

Gambling can harm people’s financial security, health, and broader wellbeing. In some cases, the consequences can be catastrophic, including job loss, bankruptcy, fraud, relationship breakdown, family violence, and suicide.62 These effects ripple through our communities.63

Gambling causes financial and mental distress

People who gamble have lower financial wellbeing than those who don’t (even after accounting for other financial and demographic characteristics).64 Those who gamble at very high levels are particularly likely to miss loan payments, use unplanned bank overdrafts, and take out payday loans.65 In extreme cases, gambling has been linked to job loss and homelessness.66

Gambling is also linked to poorer health, relationships, and wellbeing. Some people who gamble feel shame, worry, or distress about their gambling, or the financial stress that results.67 And gambling can impair family and social relationships – either as a direct source of tension, or because people gamble on their own rather than engage in other leisure activities.68

In extreme cases, gambling can be a contributing factor for suicide.69 At least 4 per cent of suicide deaths in Victoria between 2009 and 2016 were linked to gambling.70 In one study, one in six people presenting

to an emergency department for mental health care met the criteria for ‘problem gambling’.71 Most gambling financial counsellors report that they have seen clients attempt suicide. Some also report that they have seen family members of people with severe gambling harm take their own lives.72

It is difficult to isolate the harm caused by gambling; many studies only prove a correlation between gambling activity and harm. People who have other mental health or substance use disorders are more likely to gamble, making it difficult to disentangle gambling’s effects.73

But these confounding factors don’t explain all of the relationship between gambling and harm.74 When exposure to gambling products increases, for example because of regulatory changes, harm increases – even though underlying rates of mental health or substance use disorders are unlikely to have shifted over the same period.75 And in any case, gambling losses make a bad situation worse and harder to overcome.

Gambling harm is broader than ‘problem gambling’

In 2022, 1.7 per cent of adults – about 338,000 people – suffered acute gambling harm, meeting the criteria for ‘problem gambling’.76 About two-thirds of them were men.77

So-called ‘problem gamblers’ make up only a small fraction of the population at a given point in time. But gambling problems can develop quickly, without much warning, so many more people are at risk of experiencing harm at some point in their lives.78

Gambling harm is not limited to current or future ‘problem gamblers’.79 About 8 per cent of regular gamblers report at least one indicator of risky gambling – such as betting more than they can afford to lose, or feeling guilty about gambling – without meeting the clinical threshold for ‘problem gambling’. At least 500,000 Australians have asked their bank to put a gambling transaction block on their account.80

Family members, friends, and colleagues can also suffer financial and mental stress and relationship conflict as a result of someone else’s gambling.81 About 700,000 people live with someone suffering serious gambling harm.82

Gambling is also linked to domestic and family violence.83 Financial and emotional stress – particularly men’s anger or shame – from gambling can heighten the risk of violence.84 And some people use gambling as a form of escape from violence, compounding the harm.

On top of this, the broader community bears the costs of crime, health care, job losses, and other issues related to gambling.85

Pokies and betting pose particularly great risks of harm

Pokies and betting are particularly dangerous forms of gambling.

More access to pokies leads to more harm. An increase in pokies venues in a community results in higher rates of bankruptcy.86 People who live within 250 metres of a venue with pokies are about 30 per cent more likely to suffer financial hardship and poor mental health than those living more than 2 kilometres away, even after accounting for other socio-economic characteristics of the local area.87 And severe gambling harm is less common in Western Australia, where pokies are less accessible in the community.88

Nationally, about half of people suffering severe gambling harm reported that pokies were the form of gambling they lost the most on.89

Harm from pokies is relatively well-studied, because pokies have been popular for decades. There is less research on online betting, but there is emerging evidence of significant harm. In 2022, about 30 per cent of people suffering severe gambling harm reported that their biggest source of losses was betting.90 And in the US, people living in states where online sports betting has been legalised are more financially stressed, with particularly large effects for financially vulnerable households.91

1.3 The industry is built on harmful gambling

‘Problem gamblers might be hard to find in the adult population, but the opposite is true in gaming venues.’ 92

Gambling is big business, and the industry has high profit margins.93

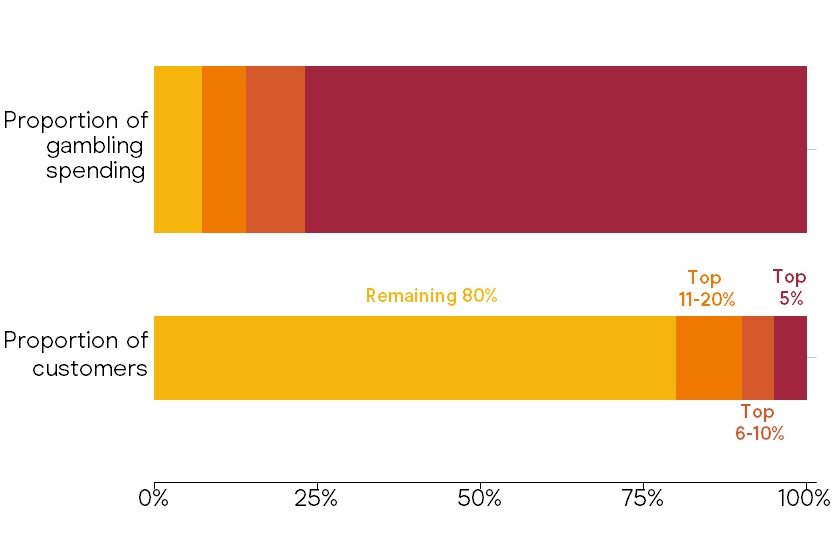

Figure 1.6: Gambling spending is highly concentrated

Debit card gambling spending, among customers with at least one gambling transaction

These profits rely heavily on a small share of high-spending individuals. Just 5 per cent of gamblers account for 77 per cent of gambling spending using debit cards (Figure 1.6). This top 5 per cent spend 10 times as much as the bottom 80 per cent combined.

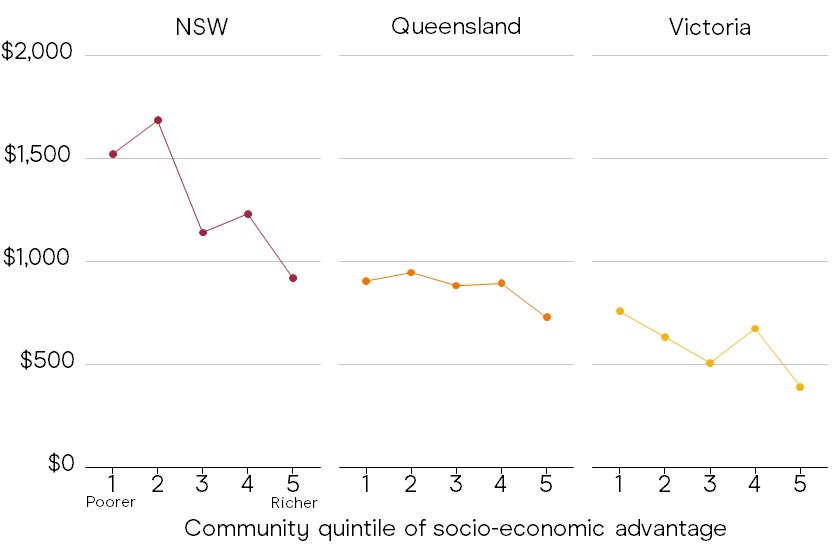

The debit card data do not include pokies spending, but surveys suggest that spending on pokies is also highly concentrated.94 And pokies losses are unevenly spread, with poorer communities bearing the brunt (Figure 1.7).95

People living in the poorest fifth of communities in NSW lose an average of $1,524 a year on pokies, compared with $922 for people living in the most well-off fifth.96 Residents of Fairfield, one of the poorest communities in Sydney, lose $3,967 a year on pokies – three times the state average.

In Victoria, the communities of Brimbank and Dandenong – both disadvantaged – have led the state in pokies losses per person for at least a decade.97

These same three communities – Fairfield in Sydney, and Brimbank and Dandenong in Melbourne – stand out for other gambling spending too.98

Figure 1.7: Average pokies losses are greater in poorer areas

Average annual pokies losses per adult

Gambling losses can exacerbate existing vulnerabilities. Within a given community, people with lower incomes are much more likely to suffer financial hardship when living close to a pokies venue.99 And people who have experienced trauma (including veterans),100 mental ill-health, and other stressors or vulnerabilities are at an increased risk of gambling harm. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities have higher rates of gambling harm than other communities.101

1.4 Prevention is better than cure

The best way to prevent gambling harm is to make gambling products safer and less ubiquitous. Governments should adopt a public health approach that aims to prevent gambling harm across the population, rather than consigning responsibility to individuals.102

‘Gamble responsibly’ has failed

Government initiatives to reduce gambling harm rely too much on individual responsibility for gambling behaviour.103 For example, government campaigns have exhorted gamblers to ‘show gambling who’s boss’, ‘become the type of man who controls the bet’, or, simply, ‘gamble responsibly’.104

The individualistic approach is promoted by the gambling industry.105 Blaming problems on a small group of ‘aberrant’ individuals absolves the industry of responsibility, and diminishes the case for stronger action by governments.

There are two main problems with this approach.

First, it doesn’t work. Individual responsibility approaches ask people to unilaterally overcome the lure of ubiquitous, highly addictive products – a very difficult task.106

Many ‘responsible gambling’ campaigns focus on raising awareness, as if lack of information about gambling harm is the main problem.

Many gamblers are aware that gambling is harming them but still find

it difficult to stop.107 And any value of these campaigns as a reminder is drowned out by the torrent of gambling advertising.

Second, individual responsibility approaches stigmatise people caught in the grip of gambling, compounding harm, and making it more difficult for them to seek help.108

A public health approach recognises that harmful gambling arises from a complex interplay of individual and environmental factors. Australian governments have started to acknowledge the value of this approach, for example in the 2018 National Consumer Protection Framework

for Online Wagering, the 2023 Murphy Inquiry, and shifting regulatory approaches in some states.109 But much more needs to be done.

1.5 The structure of this report

Chapter 2 shows that governments have failed to take the necessary steps to prevent gambling harm, mainly because of the political risks of taking on the industry and its allies.

Chapter 3 outlines a roadmap to prevent gambling harm, by reducing people’s exposure and rolling out tools that will make gambling safer.

Chapter 4 explores how governments can ensure reforms stick, by standing up to the vested interests, rebutting their self-interested claims, and coordinating reform efforts across jurisdictions.

What this report is not about

Some forms of gambling, particularly pokies, can facilitate crime and money laundering. We do not focus on these issues, although our recommendations would still help to reduce money laundering.110

Gambling taxes are a source of revenue for state and territory governments. Our recommendations would reduce overall gambling spending and, hence, this tax revenue over time. Collectively, we would be better off – the social costs of gambling are large, and borne by governments and society.111 But governments would need to find other revenue. Tax reform is not the focus of this report, but Grattan Institute has previously made recommendations for governments to improve their tax mix.112

This report mainly focuses on reducing the harm caused by pokies and betting. Other forms of gambling can undoubtedly be harmful, but are either lower risk113 or less common,114 so receive less attention in this report.

Casinos have been the subject of recent Royal Commissions and major inquiries.115 State governments should follow through on these reforms.

Our recommendations to prevent pokies harm include casinos as pokies venues.116 And our recommendations to prevent harm from online betting extend to other legal forms of online gambling, including online lotteries and online Keno.117

2 Governments have failed to protect Australians from gambling harm

Gambling is considered a heavily regulated industry in Australia, but current regulations are not particularly effective in reducing harm, let alone preventing it.

Powerful vested interests are the major barrier to reform. Grattan Institute’s 2018 report Who’s in the Room? showed how effective the gambling industry is in influencing Australian politics, punching well above its weight. Organised attempts to influence policy can create windfall gains for a few, at the expense of the many.

Many past attempts to strengthen consumer protections for gambling have been thwarted by vested interests, so gambling reform is now considered very politically risky. This political reality needs to be grappled with (Chapter 4). But it does not excuse weak regulation.

Governments have a responsibility to act in the public interest, even when it is politically challenging.

2.1 There are big holes in consumer protection

Australia’s gambling regulation is a mess and does little to reduce harm, let alone prevent it. Federal and state governments have different responsibilities, but neither are doing enough.

2.1.1 A mess of rules that do not prevent harm

Australian governments have historically legalised and promoted a wide range of gambling options.118 Today, governments oversee a tangled web of rules and codes for Australian gambling providers119 that leaves big holes in consumer protection.

The federal government has responsibility for online gambling but is yet to step up and really own this role. Online gambling is currently regulated through 60 pieces of federal and state legislation, industry codes of practice, multiple federal ministries, and the racing and gaming portfolios of state and territory governments.120 One positive recent development is a national self-exclusion register for online gambling (Box 1). But people still cannot consistently self-exclude from all forms of gambling.

State governments regulate casinos, pokies, the racing industry, and other land-based gambling, with different rules in different states.

One of the few common rules is a ban on the use of credit when gambling – credit cards are banned for gambling in casinos, hotels, clubs, at TAB outlets, and online.121

Most other regulations at best aim to slow the rate at which people lose money. For example, states prescribe maximum bets per spin, time between spins, load-up limits, and other pokies design features;122 and regulate opening hours, service of food and alcohol,123 responsibilities to intervene,124 and reporting requirements.125 Collectively, these rules – if enforced – may reduce gambling harm but ultimately don’t prevent it and fail to protect against catastrophic losses.

No state or territory has yet implemented the best, simplest approach to preventing gambling harm: mandatory pre-commitment (see Chapter 3).126 Tasmania is currently implementing a scheme for pokies that will be best in class when it is operational by late 2025.127 Victoria and Western Australia have also announced mandatory pre-commitment schemes for pokies to be rolled out in the next year or so.128 And Queensland will introduce a mandatory pre-commitment scheme by the end of 2025, but it will be limited to casinos.129 These are critical steps in the right direction, but there is still a long way to go (Chapter 3). NSW has been especially timid in its efforts.

Box 1: One shining light – BetStop

Australians now have a way to self-exclude from all (legal) online betting. BetStop is the National Self-Exclusion Register, launched in August 2023.a

Australians can register with BetStop to self-exclude from all licensed online and phone gambling for a minimum of three months and up to a lifetime. About 22,000 people had self-excluded as at July 2024. Half of those on the register were younger than 30.b

Providersc are not allowed to open an account for, accept a bet from, or market to self-excluded individuals.

BetStop still leaves gaps in the coverage of online gambling: BetStop was established under the Interactive Gambling Act, which excludes lotteries and Keno.d

And the BetStop system can’t exclude people from any land-based forms of gambling.

Some states have self-exclusion schemes for land-based gambling. The South Australian scheme enables people to self-exclude from casinos, pokies venues, racing, and lotteries, and includes a third-party exclusion option for friends or family members to intervene.e NSW is developing a similar scheme.

a. Rowland and Rishworth (2023).

b. ACMA (2024b).

c. There are currently more than 150 online and phone interactive gambling providers licensed in Australia: ACMA (2024a).

d. Grogan et al (2023). The government is currently reviewing this exclusion: Rowland and Rishworth (2024).

e. SA Office for Problem Gambling (2021).

2.1.2 Many rules are not even enforced

Inquiries at the state and federal level in recent years have identified regulatory failures in consumer protection, including over-reliance on individual responsibility,130 over-reliance on the industry to self-regulate,131 little follow-up or enforcement,132 and inadequate penalties.133

Most venue-based consumer protections rely on individual staff to track gambling risk and know when and how to step in – a difficult task which staff have little incentive to undertake.

Recent Royal Commissions and reviews of casinos in NSW, Victoria, Queensland, and WA paint a grim picture of flagrant disregard for their communities and the rules under which casino licences are granted.134

Many regulators don’t do enough to check that operators adhere to their licence conditions. Some regulators appear to be well out of their depth: the Perth Casino Royal Commission found the regulator lacked an ‘adequate or accurate understanding of its role’, and the Victorian Royal Commission found that Crown Melbourne ‘bullied the regulator’.135

Even where misconduct is investigated, and a gambling provider is found to have breached its licence, the fines are often so low that they can simply be accommodated as a cost of doing business.136 The Murphy Inquiry found that ‘current penalties for breaches of online WSPs’ [wagering service providers’] responsibilities to their customers neither match the seriousness of the breaches nor provide an adequate deterrent to change behaviour’.137

2.1.3 Gaps in the current regulatory arrangements

There are many gaps in the regulation of gambling in Australia. Legislation is outdated, and regulators lack the powers (and data) they need to do their job.138

There are few measures in place that directly prevent gambling harm. Mandatory pre-commitment with upper limits on losses could provide that safety net (see Chapter 3).

The lack of good public and administrative data on gambling activity also undermines regulators’ ability to identify and prevent harm, and makes independent analysis difficult.139 The most detailed data on gambling activity is held by the gambling companies themselves.

Most prominently, the federal government has taken more than 14 months to respond to the Murphy Inquiry into online gambling, which handed down 31 recommendations in 2023 with multi-partisan backing. A core recommendation of the inquiry was a full ban on gambling advertising. The delayed response has left big gaps in consumer protection, and demonstrates once again how politically challenging it is to achieve good policy in this space.

2.1.4 Barriers to effective treatment and support

As well as inadequate prevention measures, there are also deficiencies in the system that is meant to help people suffering acute gambling harm.140

Gamblers face big barriers to seeking help in the first place. Many people feel shame or stigma about ‘having a gambling problem’, internalising the ‘responsible gambling’ messages that paint excessive gambling as a failure of self-control (Chapter 1).141 Just a fraction of people suffering gambling harm actually seek help.142 Even fewer seek help early, before they reach a crisis point, because many people believe that only ‘problem gamblers’ need help.143

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, and people living in rural and remote communities face particularly big barriers to getting support.144

Health and social service professionals in other areas often fail to recognise or refer people with gambling problems. For example, people with mental ill-health or substance use problems have higher rates of gambling problems than the general population,145 but screening and referral pathways are inconsistent, and gambling problems can go unrecognised or unaddressed.146

There is no guarantee that even people who overcome these barriers and find a support service receive effective support.147 There is no established best-practice model of care in Australia; each service designs its own treatment protocol, with limited clinical evidence to draw on.148 In some states, treatment services are not regularly evaluated, so governments and providers don’t know if the services they are providing actually work.149 And different kinds of support, such as psychological support (including for co-occurring mental health conditions) and financial counselling, are rarely integrated.

2.2 Why governments haven’t taken stronger action

There are two main reasons that Australian gambling regulation is so weak. The first is that state governments rely on the tax revenue from gambling. The second is that gambling is such a politically powerful industry, with many powerful allies, governments are scared to take them on.

2.2.1 Gambling taxes are an important source of revenue

State governments deregulated gambling in the 1990s, in part to open up a new revenue stream.150 Gambling taxes today remain an important source of revenue for state and territory governments. In total, state and territory governments collected about $9 billion in gambling taxes in 2022-23 – about 8 per cent of their total tax revenue.151

In most states and territories, except the Northern Territory, gambling’s share of tax revenue has declined over the past two decades. But gambling is still the fifth-largest tax base for states and territories overall, after payroll, stamp duty, property, and motor vehicle taxes (Figure 2.1).152

Tax collected varies widely across different forms of gambling. Governments collect an average of just 11 cents for every $1 spent on betting,153 but 67 cents for every $1 spent on lotteries, and 31 cents for every $1 spent on pokies.154

Figure 2.1: Gambling is a small but important source of revenue for most states and territories

Tax revenue by category, share of state’s total tax revenue, 2022-23

Gambling taxes return some of the industry’s excess profits to the public.155 Taxes may also discourage some gambling activity, by making the odds even less favourable to gamblers.156 And of course, state governments use the revenue raised to pay for other services.

But state governments – and the community – also bear significant social costs associated with gambling.157 Tax considerations should not be a major barrier to reform.

2.2.2 …but political risk is the biggest barrier to reform

Gambling is one of Australia’s most politically powerful industries, which makes gambling reform high risk politically. This is the main reason current regulation is so weak.

Past reform pushes have failed because of well-funded, coordinated attacks by vested interests. The most visible example of this was the Gillard government’s backflip on pokies reform (see Box 2). More than a decade later, there is still the lingering threat that the pokies industry could do it again: a former NSW gambling minister, when considering pokies reforms, said he was told ‘we will do to you what we did to Julia Gillard’.158

The gambling industry’s political power lies in its ability to influence elections. They can make their presence known locally, with pokies providers in almost every electorate, stoke community fears about loss of jobs and services (Chapter 4), and they exert financial influence too.

Box 2: Gillard’s pokies backflip

After the 2010 federal election, Independent MP Andrew Wilkie struck a deal with Julia Gillard to support her minority government in exchange for the rollout of a mandatory pre-commitment scheme for pokies (as recommended at the time by the Productivity Commission).a

Despite pokies reforms being popular with voters, an organised effort from pokies businesses, led by Clubs Australia, ultimately led to the Gillard government walking away from its agreement with Wilkie in early 2012.b

Clubs, hotels, and other businesses that financially benefit from pokies fought the reforms, exaggerated the impacts, and ramped up their political donations over the period (see Figure 2.3). They also ran a very effective advertising campaign.c

The main Clubs Australia campaign, called ‘Won’t Work, Will Hurt’, included mail to residents in marginal Labor electorates in NSW and Queensland, community rallies across NSW, large billboards naming local members with the slogan ‘Why don’t you stand up for our community?’, and drink coasters and T-shirts for club staff with the slogan ‘Who voted to put me out of work?’d

The clubs reportedly had a war chest of $40 million for the campaign, but only needed $3.5 million to get the result they were looking for.e

a. Productivity Commission (2010).

b. Wood et al (2018, pp. 73–74); and Lewis (2023).

c. Panichi (2013).

d. Lewis (2023).

e. Ibid.

For example, political donations from gambling businesses were instrumental in Tasmania’s 2018 election, where the future of pokies in pubs and clubs was a key issue.159 When the Tasmanian Labor Party proposed removing pokies from pubs and clubs, the gambling industry swung behind the other side. The Tasmanian Liberal Party won the election, with nearly 90 per cent of the party’s declared donations coming from gambling interests (a 10-fold increase on the amount gambling groups had given in the previous election).160 The hotels lobby also ran an intensive advertising campaign during the election.161

This recent history makes Tasmania’s current pokies reforms all the more remarkable (see Box 6 in Chapter 3).

Gambling donations flow overwhelmingly to the major parties, who are most likely to form government.162 Clubs and hotels with pokies interests are the biggest gambling donors, followed by casinos (Figure 2.2). And gambling donations show a pattern of spiking when the ‘political heat’ rises, on pokies reform in particular (Figure 2.3 and Box 2).

The biggest spike was in 2018-19 (Figure 2.3), when the pokies industry made big donations in the lead up to the Victorian election in November 2018, mostly backing Labor.163 The Australian Hotels

Association (representing pubs and hotels with pokies across Victoria) was reportedly trying to prevent The Greens from winning the balance of power in the state election, because of The Greens’ strong anti-pokies policies.164 The industry funded its donations through a levy on pub pokies.165 Labor ultimately won the election.166

NSW stands out in having banned political donations from gambling businesses because of the potential for influence and perception of influence.167 But gambling interests in NSW still can and do donate at the federal level.

In 2018, Grattan Institute published a report on vested interest influence in Australian politics. It found that highly regulated industries, including gambling, lobby far more than other businesses, unions, charities, and consumer groups. And the gambling industry particularly stood out, as an industry gaining far more access and influence than you might expect given its relatively small contribution to the economy.168

It is no surprise that the gambling industry knocks on politicians’ doors: government decisions can make a big difference to the industry’s bottom line.169 The worry is that politicians are not getting a balanced view of the issues when they spend so much time talking to the industry and rely on political donations from the industry.170

Figure 2.2: Political donations from the gambling industry are largely from pokies interests (clubs and hotels)

Political donations and other receipts from gambling interests, nominal

Figure 2.3: Gambling donations spike with pokies reform attempts

Political donations and other receipts from gambling interests, nominal

Australia’s most powerful gambling lobbyists include pokies operators and manufacturers (ClubsNSW, the Australian Hotels Association, and Aristocrat Leisure), betting companies (Responsible Wagering Australia,171 and Tabcorp), and the main casino operators (Star Entertainment Group, Crown Resorts, and Federal Group in Tasmania).

Gambling companies and peak bodies apply political pressure through every avenue to protect their interests. This includes hiring commercial lobbyists,172 meeting directly with key ministers,173 hosting functions for policy makers and powerbrokers,174 public advertising campaigns,175 targeted seat campaigns,176 recruiting powerful allies,177 and making political donations.178

ClubsNSW is so powerful it has managed to get three NSW governments to sign pre-election memorandums of understanding (MoUs), committing that, if elected, the government would not implement policies that threaten clubs’ gambling revenue.179

Federal rules around lobbying and political donations are weak,180 enabling those with motivation and resources to have more say – and sway – over public policy than they should.

Box 3: The gambling industry has powerful allies

The gambling industry rarely stands alone in resisting gambling reform efforts. Gambling is intertwined with our local pubs and clubs, with our major sporting codes, and with Australia’s major television networks.

When pokies reforms are on the table, local clubs are the sympathetic face of industry obstruction. And Australia’s favourite sports, and free-to-air TV channels, have led the resistance to a gambling advertising ban.a

The industry has forged these alliances, striking revenue-sharing deals with the major football leagues,b and embedding itself to the point that clubs and TV networks think they need the gambling dollars.

While these arguments are mostly hot air (as Chapter 4 shows), they successfully create fear, helping to make the gambling industry ‘untouchable’.

a. Seccombe (2024); and Keane (2024).

b. McClure (2022); and McGrath et al (2023).

3 A roadmap to prevent gambling harm

If Australian governments are serious about preventing gambling harm, they will need to bolster their efforts and take action to both reduce the pervasiveness of gambling in Australia and make gambling safer.

Gambling normalisation starts young, and sports betting advertising is a major culprit. The federal government should ban all gambling advertising, sponsorships, and inducements.

For those who choose to gamble, mandatory pre-commitment with maximum loss limits would ensure they no longer lose more than they can afford. The federal government should establish a national pre-commitment system for online gambling, and state governments should roll out state-wide pre-commitment for pokies. In parallel, the federal government should investigate the feasibility of a universal system across all gambling environments.

These recommendations would make gambling much safer, but they will take several years to implement. In the meantime, governments should improve support services to help those suffering harm now.

3.1 Reduce exposure to gambling

The pervasiveness of gambling in Australian society normalises it for young people and makes it harder for people suffering gambling harm to break the cycle.181 Three-quarters of Australians believe gambling is too prevalent, and two-thirds think it is ‘dangerous for family life’.182

Australians are mainly exposed to gambling through advertising,183 at local pubs and clubs that host pokies and betting facilities,184 and through video games.185

3.1.1 Ban gambling advertising and inducements

Gambling advertising exposes large numbers of Australians, including children, to a dangerous product,186 and increases losses, with little corresponding economic or social benefit.187 Yet gambling ads are everywhere, implicitly sanctioned by our weak regulations.

A full ban is important. Partial advertising bans, by definition, leave gaps, and advertisers will capitalise on these gaps. Gambling advertising on TV actually increased after restrictions on gambling ads during live sport were introduced in 2018 (Figure 3.1). Similarly, in the 1970s, a ban on tobacco advertising on radio and TV just pushed ads into print media, billboards, and sponsorships instead.188

Even if a partial ban resulted in fewer gambling ads on TV, it would still allow widespread exposure to gambling advertising (including for children). It may also encourage advertisers to more aggressively market their products in other ways, such as through direct marketing and inducements, which are known to be high risk for people suffering gambling harm, and encourage children to perceive gambling as lower risk than it is.189

The federal government should ban all gambling advertising and inducements, as recommended by the multi-partisan Murphy Inquiry last year.190 The Murphy Inquiry called for a comprehensive ban on ‘all gambling advertising on all media’ (broadcast and online) to be phased in over three years, and a ban on inducements ‘without delay’.

A phased approach would give sporting bodies and broadcasters time to find replacement revenue.191 Despite alarmist claims, this would not be a fatal blow to either (Chapter 4).

3.1.2 Rein in the pokies over time

Pokies are far too widespread and accessible, particularly in NSW, Queensland, and the NT (see Figure 1.3). Western Australia’s ‘destination model’, where gaming machines are only available at Perth Casino, appears to have paid off in lower rates of gambling harm.192

Limiting the sheer number of venues where pokies are present is more important than simply limiting the number of machines. While a destination model such as Western Australia’s is a long way off for the rest of the country,193 state governments should actively reduce the number of machines and venues.

Figure 3.1: Gambling ads increased after a partial ban in 2018

Number of gambling ads on TV between April and June, by time of broadcast

State governments set caps on the number of pokies, so this is a tool they can use to lower numbers over time. Other policies, such as NSW’s 2-for-1 trading arrangements (where for every two pokies

licences traded, one must be forfeited) can support the goal of reducing pokies numbers over time.194

The biggest gains come from substantial cuts that reduce the number of venues with pokies.195 But achieving a big reduction in pokies numbers quickly would probably require massive buyback schemes, costing hundreds of millions of dollars, if not more.196 Buyback schemes would be better used to support the rollout of mandatory pre-commitment (see Section 3.2) rather than as a stand-alone policy.197

The proliferation of pokies is a problem that state governments should chip away at over time, at the very least to avoid making things worse.

3.1.3 Warn people about gambling in games

Many video games include gambling-like features that familiarise children with gambling and can be a gateway to other gambling. Loot boxes, in particular, are a common gambling-like feature in electronic games and have been linked to gambling problems (see Box 4).

Most Australian teenagers play video games, and more than 20 per cent of adolescents in NSW reported purchasing loot boxes in the past 12 months.198

Australia’s game classification system was recently amended to require games to be rated M+ if they include ‘in-game purchases linked to elements of chance’ (such as loot boxes), and rated R if they involve ‘simulated gambling’ (such as social casinos).199 This leaves loot boxes still available to minors.200

Australia should introduce a gambling warning label,201 so that people know when a game contains gambling-like features. This would help gamers of all ages avoid exposure to gambling if they wish, and it may be particularly helpful for parents to reduce their children’s incidental exposure to gambling.

3.2 Roll out mandatory pre-commitment with maximum loss limits

Even with reduced exposure to gambling, many Australians would still choose to gamble. The most effective way to make gambling safer (and ultimately more enjoyable) is to introduce mandatory pre-commitment with maximum loss limits for people using pokies or gambling online.202

Under our proposed mandatory pre-commitment system (Box 5), a gambler would choose their limits in advance – before they lose track of time, start chasing losses, or are otherwise compromised in their

decision making (see Chapter 1). The system would then enforce these limits.

The scheme should have regulated upper limits,203 to prevent catastrophic losses, particularly given the evidence that many people, when asked to set limits in advance, will choose an unrealistically high level,204 such as $1 million a day.205

The system needs to be mandatory to be effective, but should have very little impact on people who gamble in moderation (Box 5). The system is there to prevent catastrophic losses for people whose decision making is impaired by addiction, alcohol, or anything else. It’s a seatbelt for gambling: it should hardly be felt when everything is going smoothly, but prevent serious harm when something goes wrong.

Box 4: A loot box

Loot boxes are virtual containers that can be purchased or won in video games. When opened, players receive surprise items, such as weapons, special abilities, and skins (cosmetic items). These items can enhance player performance or have aesthetic and social value due to their rarity.

Gambling and purchasing loot boxes are very similar. They both involve spending money for uncertain reward, encouraging you to continue purchasing until you obtain the desired item or win money.

People who purchase loot boxes are more likely to gamble, and suffer gambling harm, in future.a For example, Australian adolescents who purchased loot boxes were three times more likely to engage in high-risk gambling than other adolescents.b

Young people are especially vulnerable because high impulsivity is common in adolescence,c and is linked to high-risk gambling.d

There is not enough evidence to establish whether loot boxes lead people to other forms of gambling, or whether people who are drawn to gambling are also attracted to loot boxes.e But either way, there are good reasons to regulate loot boxes: to reduce exposure to gambling, or to reduce harm in another gambling mode for people at risk, including young people.

a. Brooks and Clark (2023); Montiel et al (2022); and Garea et al (2021).

b. Hing et al (2022).

c. Carvalho et al (2023).

d. Secades-Villa et al (2016).

e. For example, in one survey, some people reported that they thought purchasing loot boxes caused them to gamble down the track, while others reported that they thought gambling caused them to purchase loot boxes later: Zendle and Cairns (2019) and Spicer et al (2022).

Box 5: Mandatory pre-commitment with maximum loss limits: our proposed scheme

This report recommends a national scheme for online gambling and state-based schemes for pokies, with the following features:

Choose your limits before you gamble: Mandatory pre- commitment means everyone needs to choose how much they are willing to lose before they start gambling.

Maximum loss limits: There should be a regulated upper limit on losses, for example $100 a day, $500 a month, and $5000 a year.a

Lowering limits: Anyone should be able to lower their personal limits at any time.

Raising limits: A time delay of at least 24 hours should apply to raising your personal limits, up to the maximum limits. There should be a process available to apply for higher limits (beyond the default maximum) if gamblers can demonstrate capacity to sustain higher losses.b

Self-exclusion: Limits can be set to zero to self-exclude. Pre-commitment schemes could also link to state and national self-exclusion registers.

Mandatory matters: Mandatory schemes – where limit setting is required of all players – are much more effective in preventing harm than voluntary schemes – where customers can opt in and out (including after hitting their chosen limit).c Many studies have found voluntary schemes to be ineffective in limiting losses,d largely because people opt out even when prompted.e

Minor inconvenience: The downside of a mandatory scheme is that it applies to many people who won’t ‘need’ it. But it is not a major imposition. Pre-commitment doesn’t require much more time or effort than identity verification (which is already required for online betting). Most people spend very little so would be unlikely to ever hit the maximum limits anyway.f

Privacy protections: A mandatory scheme needs strong privacy safeguards. Individual records can and should only be used to inform people of their own spending and help them stick to the limits they choose. Identifiable data should not be available to the gambling industry, credit agencies, bureaucrats, or anyone else for other purposes.g

a. These are the limits set for Tasmania’s pokies pre-commitment scheme: See Box 6.

b. As recommended by the Tasmanian Liquor and Gaming Commission in 2022.

c. Productivity Commission (2010); Thomas et al (2016); Delfabbro and King (2021); and Ladouceur et al (2012).

d. Wohl et al (2024); Delfabbro and King (2021); and Ladouceur et al (2012).

e. Delfabbro and King (2021).

f. See Section 4.2.3.

g. In accordance with the Privacy Act 1998 (Cth). However, deidentified, aggregated data could be safely used for research to inform better harm prevention (Section 3.2.2) – just as an individual’s Census form is never published, but average statistics on their state are.

Regulators should be wary that setting limits on how much people can lose while gambling creates an incentive for the industry to more aggressively try to increase its customer base. This makes the ban on all gambling advertising and inducements (Section 3.1.1) all the more important.

3.2.1 Mandate pre-commitment with maximum loss limits for online gambling and pokies

The federal government should establish a national mandatory pre- commitment system for online gambling, and state governments should implement state-wide mandatory pre-commitment schemes for pokies. This will go a long way to preventing harm from the two most risky and widespread forms of gambling.

Mandate pre-commitment with maximum loss limits for online gambling

The federal government should establish a national mandatory pre-commitment system across all online gambling – including online betting, phone gambling services, online lotteries, and online Keno – with maximum loss limits.

The system could be run through the federal government’s BetStop system (the national self-exclusion register), or could draw on that model.206 Under the BetStop system, all online and phone gambling providers licensed in Australia must verify customers’ identities, and check that they are not on the self-exclusion register, before they can place a bet.207

This system could be extended to support mandatory pre-commitment for all customers.208 Providers would need to verify customers’ chosen limits – in the same way they currently verify customer identity –

and not allow losses beyond those limits. Providers should also give warning messages to customers as their limit approaches, so it doesn’t come as a shock.

When setting limits, customers could be offered a set of default limits and the opportunity to lower those limits, or raise them up to the regulated maximum limits. They should only be allowed to set limits above the maxmimum if they can demonstrate the financial capacity to sustain those losses.209

Once a national pre-commitment system for online gambling is well established, it may be possible to extend the system to cover other forms of gambling too.

Mandate pre-commitment with maxmimum loss limits for pokies

Mandatory pre-commitment for pokies should be a priority given that pokies are a particularly harmful form of gambling (see Chapter 1). Pokies are designed to make you lose track of time and money.

Pre-commitment with maximum loss limits would prevent things getting out of hand.

Tasmania is currently implementing a state-wide mandatory pre-commitment scheme for pokies, with maximum limits, that should guide other states (Box 6). State-wide schemes should apply to all venues with pokies licences, including casinos. 210

Pokies venues would need to ensure that people can only gamble on pokies using their registered card, as per the Tasmanian model. Compliance with the mandatory scheme should be a condition of holding a licence.

Cashless gaming is currently a major focus for NSW, and is an important part of tackling money laundering via pokies,211 but is not an essential pre-cursor for mandatory pre-commitment.

Most pokies already have card readers (for example, for reading loyalty cards), and are connected to a central monitoring system for tax purposes, but machines that don’t would need to be modified212 to continue operating.213 People could still pay with cash, as long as the machine only operates when linked to a valid card.214 State governments should mandate venue compliance with the scheme and could offer to buy back machines that do not comply.215 Pokies venues would then have the option of retrofitting or upgrading their machines to comply, or if they prefer, they could sell their licences for non-compliant machines back to the state government.

Box 6: Tasmania’s pokies reforms are the best Australian model

Tasmania is implementing a mandatory card system for pokies, covering every venue in the state (hotels, clubs, and casinos). The scheme is expected to be up and running by late 2025.a

People will need to show ID to register for a card, with a Monitoring Operator in charge of verifying that each person only registers once.

The card will be pre-set with default limits of $100 per day, $500 per month, and $5,000 per year. People can choose to reduce their limits, at any time, with immediate effect.b Anyone who wishes to increase their limit above the default limits will need to show proof that they are able to sustain higher losses.c Gamblers will get warning messages as they approach their limit, and if they reach their limit, play will cease and the card will be inoperable until the limit refreshes.d

In 2022, the Tasmanian Gambling Commission estimated this state-wide system would cost about $10 million to develop and implement in all licensed venues.e Tasmanian pokies are largely coin-based, so machines will be fitted with card-readers and linked to a revamped central monitoring system that will enforce pre-commitment and limits. The final cost of implementing and monitoring the system won’t be clear until the scheme is up

and running. Who foots the bill (industry, taxpayers, or some combination) is also still to be determined.

a. Holmes (2024).

b. Card holders can also increase their limit back up to the default limits, but with a time delay that is still to be determined.

c. This process is still to be determined.

d. Tasmanian Liquor and Gaming Commission (2022).

e. Ibid.

Offering a buyback option should reduce pokies numbers while giving the industry some choice in how they manage the impact of the mandatory scheme on their business. Buyback costs could be substantial if lots of machines are non-compliant and venues opt to surrender their licences. While this is unlikely – given how profitable pokies are216 – a substantial reduction in pokies numbers would come with great social benefits in reducing exposure to gambling,217 so governments should not shy away from the risk of a higher (one-off) cost.

Figure 3.2: Different states have different starting points for rolling out pokies pre-commitment

The ACT is currently running a small buyback scheme, offering $15,000 per gaming machine authorisation surrendered and $20,000 per authorisation if a venue goes ‘pokie-free’.218 The extra incentive to go ‘pokie-free’ supports the goal of reducing exposure to gambling.

State governments should focus their effort on rolling out state-wide mandatory pre-commitment, with the buyback option as a supporting policy only. The buyback option should therefore be primarily for non- compliant machines, but could be extended to all machines in a venue if the venue goes ‘pokie-free’.219

There are different implementation considerations in each state (see Figure 3.2). Some states, such as Victoria, already have the necessary functionality across all their machines, so can implement mandatory pre-commitment more easily.220 In contrast, the ACT lacks a central monitoring system for its pokies, adding an extra implementation hurdle.221

Some states just have a lot more pokies than others. NSW has a particularly big job, with a lot more gaming machines than any other state (see Figure 3.3), and the majority requiring an upgrade or retrofit to enable limit setting. More importantly, the central monitoring system in NSW is only one-way (rather than two-way, as it is in other states), and a two-way system is needed for state-wide pre-commitment. While many of the implementation challenges are greater for NSW, so are the benefits.

Figure 3.3: NSW stands out for sheer number of pokies

Pokies operating as at 30 June 2021

3.2.2 Investigate the feasibility of a single universal pre-commitment system for gambling

In parallel to the reforms above, the federal government should investigate the feasibility of a single system for mandatory pre-commitment across all gambling environments. Rather than setting separate limits for pokies, online betting, and other forms of gambling, the ideal would be a single limit across all forms of gambling.

This is a relatively novel concept, but there are some international examples that show it can be done.

A universal system may need to be administered by a national agency (as it is in Germany and Norway) to keep track of people’s nominated limits and spending across providers.

The feasibility study should:

- Examine international models, consider bespoke options, and make a recommendation if there is a workable model for the Australian context (or a series of costed options);

- Consider whether a national gambling regulator would be required to administer and enforce the system, or whether there are existing institutions that could take on this role; and

- Identify the measures required to protect people’s privacy.

If feasible, a universal pre-commitment system could give gamblers better information about their own spending patterns and regulators better information on broader patterns of gambling and gambling harm – data that currently only the industry itself holds. The online and pokies pre-commitment schemes recommended in Section 3.2.1 also offer this side benefit. This data can and should be deidentified to protect people’s privacy.

3.3 Improve gambling support services

Australia needs more accessible and effective support services for people suffering gambling harm. While some people might just want information on self-management tools or peer supports, others may need one-off or ongoing counselling, financial counselling, or more intensive psychological support. Gambling treatment and support services should be a responsibility of health ministers, not industry ministers.222 Recognising gambling harm as a health issue should improve models of care and reduce barriers to integrating gambling treatment with other health services.223

Australia needs a stronger evidence base on the most effective supports for people suffering gambling harm. Federal and state health ministers – through the national Health Ministers’ Meeting Forum – should commission a review of gambling support services to:

- Identify the most effective, and cost-effective, models of care.

- Map the availability of current services and identify gaps:

- Are the right services available when and where people need them? Are more resources needed to meet demand?

- To what extent are integrated treatment options available to people with co-occurring mental illness, substance use, or other addictions?224

- Develop strategies for screening and referral:

- What is the best approach to screening and referral for gambling problems across frontline health and financial services?225

- Is there scope to screen for emerging gambling problems via patterns of gambling activity?226

- Outline priorities for research and evaluation:

- Where is new research needed to improve models of care?

- Are publicly funded services regularly evaluated, and are results shared across jurisdictions?

- How can governments and industry better collect or share data to inform research and harm-prevention efforts?

Our other recommendations to reduce gambling exposure and introduce mandatory pre-commitment should significantly reduce gambling harm, and, consequently, demand for help services. But if the review finds that more funding for services and/or research is needed, governments could make up the gap by increasing gambling taxes and closing tax loopholes.

The federal government could impose a levy on online betting providers, as recommended by the Murphy Inquiry.227 And state and territory governments could close generous tax concessions and support arrangements for the gambling industry.228 Tax concessions for NSW clubs actually exceed the amount of tax they pay on their pokies revenue.229

State governments give away at least $1.2 billion in pokies tax concessions for clubs230 – more than enough to cover the cost of improving support services.

4 Stand up to the vested interests

Preventing gambling harm will reduce the gambling industry’s profits, so governments need to be prepared to stand up to strong vested interest pushback. The industry has a track record of thwarting reforms, including by stoking community fears about unintended consequences. These fears don’t stand up to scrutiny.

The time is right for federal, state, and territory governments to come together to implement a coordinated reform package. Taking action together is likely to be the most effective way to take on the vested interests.

4.1 The window for reform is open

A window for reform to prevent gambling harm is open right now.

Recent Royal Commissions, reviews of Australian casinos, and the NSW Crime Commission’s inquiry into money laundering through pokies have collectively sparked outrage around the country.

And disquiet about the proliferation of online gambling harm triggered the 2023 Murphy Inquiry, which made 31 recommendations supported by multi-partisan consensus – a rare feat. The federal government has taken more than 14 months to respond to the inquiry, but leaks last month on the potential response231 sparked protracted debate in the media, parliament, and Labor’s own caucus – showing how widespread the public support for reform is.

After decades of failed attempts, some state governments, notably Tasmania, are finally taking action on pokies.

And in NSW – the state with almost as many pokies as the rest of the country combined – the most recent state election was fought at least in part on pokies reforms. While the policies being debated were more focused on money laundering risks than gambling harm, both major parties brought policies to the table.

This is the political moment for multi-jurisdiction, multi-partisan reform.

4.1.1 Strength in numbers: coordinate reform across jurisdictions

Taking action across all jurisdictions is likely to be the most effective way to stand up to the vested interests. It makes it harder for the industry to go after individual politicians, parties, or governments, as it has done in the past (see Chapter 2).

Every jurisdiction has work to do in preventing gambling harm, and reform will be easier and more effective if jurisdictions coordinate their efforts. But that shouldn’t mean delaying state-based reform efforts, or waiting for laggards. If some jurisdictions fail to step up, others should push ahead without them.

The federal government should assemble a National Taskforce and consider financial and other incentives to bring everyone to the table. For example, the federal government could take full responsibility for regulating online betting, while still enabling states to collect online betting revenue through their point-of-consumption taxes.

The National Taskforce should:

- Implement the roadmap in Chapter 3 to prevent gambling harm;

- Share lessons and work through any state/territory border issues; and

- Consider closing tax concessions, raising taxes on under-taxed forms of gambling, and/or measures to lift low-taxing jurisdictions to align with other states.232

Coordinating reform across jurisdictions will make the changes simpler for people to navigate and strengthen governments to withstand vested interest pushback. This will be especially important given the roadmap will take several years to fully implement.

4.2 The industry’s objections are mostly hot air

The gambling industry tries to make itself untouchable by stoking community fears. It argues that stronger gambling regulation will push people towards illegal gambling, or threaten things Australians care about: sport, clubs, jobs, or the occasional flutter.

These fears don’t stand up to scrutiny. Governments should call out the industry’s self-interest, and not be tempted to ‘buy off’ vested interests (Box 7). Gambling licences are a privilege granted by governments – they are not a right – and they do not override government responsibility to legislate in the best interests of the Australian people.

Box 7: Resist the temptation to buy off vested interests

Vested interests will probably call on governments to ‘compensate’ them – for example through new grants for community clubs or sporting codes. Federal and state governments should resist calls for indefinite, untargeted, or no-strings-attached assistance.

These sorts of grants are rarely the best use of public money and carry risks of political interference and poor value for money (think ‘sports rorts’).a Grant schemes administered by clubs also have a poor track record for probity.b

And investing ‘just’ a small amount of money is unlikely to quieten the vested interests anyway.

The pokies buyback option in Chapter 3 should be priced well below market value, giving venues an opt-out option only. This will offer some transitional support, but it should not fully ‘compensate’ for expected future pokies revenue that would only be achieved if our lax regulatory regime, and associated social harm, continues.

a. Wood et al (2022).

b. Victorian Public Accounts and Estimates Committee (2023); ACT Audit Office (2018); and Audit Office of New South Wales (2013).

4.2.1 Sport, and free-to-air TV, will survive without gambling ads

Industry lobbyists claim that restricting or banning gambling ads would jeopardise the financial viability of sport, or the free-to-air TV industry. But these industries have adapted to advertising bans in the past, and would do so again.

Betting companies spend a lot on marketing to sports fans. They are highly visible through team and stadium sponsorships, broadcast and online ads, and deals with sporting codes.233

But gambling ads are not irreplaceable. If gambling advertising was phased out, as we recommend, those ad spots would not fade to black, nor be given away for free. Other advertisers would emerge. They might not be willing to pay quite as much, but the difference would be much less than the face value of the gambling advertising revenue.234

Sport sponsorships and ad spots are expensive because they are valuable: an opportunity to market to a highly engaged audience.235 Even former AFL CEO Gillon McLachlan (now CEO of Tabcorp) acknowledged that at least part of lost gambling sponsorship revenue would be replaced.236

The history of advertising regulation suggests that Australian sport and broadcasters will adapt (see Box 8).

Some clubs are already forging ahead and swearing off gambling sponsorships as part of state government initiatives.237 For example, the South Sydney Rabbitohs were previously sponsored by Luxbet and Sportsbet, but joined the NSW Government’s ‘Reclaim the Game’ program in 2022.238 The club’s sponsorship revenue grew from $8.9 million in 2021 to $11 million in 2023.239 These programs are a good model for smoothing the transition away from gambling ad revenue for sport and media companies.240

4.2.2 Clubs can still serve their communities with less pokies revenue

Clubs argue that their pokies profits support the community. But estimates of their community benefits are highly inflated, and their most valuable contributions don’t rely on pokies profits.

Clubs’ net community contribution is small

Clubs claim they make direct community contributions and generate billions of dollars of social and economic value. For example, in 2022- 23, NSW clubs gave $121 million in community grants, and claimed that their social value amounted to $9 billion. Victorian clubs reported ‘community benefits’ worth $312 million.241

These supposed benefits are a small fraction of community pokies losses. The average NSW local government area received $946,000 in club grants in 2022-23, but lost 38 times that – $36 million – on pokies based in clubs.242

But even these estimates are preposterously inflated.243 The main beneficiaries of ‘community grants’ are clubs themselves, and their affiliated entities. In NSW, just four of the 50 largest grants were made to registered charities.244 Most of the rest went to clubs themselves, or their associated golf or rugby league clubs.245 And 71 per cent of claimed community benefits in Victoria covered clubs’ own operating expenses, such as wages and utilities.246 Yet these ‘contributions’ are generously rewarded through tax concessions.247

Job transitions can be managed smoothly

Clubs and hotels also argue that tighter pokies restrictions would imperil jobs. This is misleading.

If the gambling industry declined, new opportunities would open elsewhere as consumers spent their money on other products. Very few people are employed in gambling-specific jobs: just 5 per cent of club employees, and 3 per cent of pub employees, are pokies or betting attendants.248 Hospitality skills are highly transferable, so workers are likely to be in demand elsewhere in the service sector.

The lead time for implementing regulatory changes would give workers, clubs, and hotels plenty of time to adjust to any changes in staffing.249 The turnover rate is already high: just 28 per cent of people who were working in the clubs industry in 2016 were in the same industry five years later.250

Box 8: Sport and TV companies adapted to the tobacco ad ban

The tobacco industry was a major sponsor of sport in the 20th Century, just like the gambling industry is today. Governments slowly pushed it out, first banning broadcast ads in 1976, and then sponsorships in

1996.a

The tobacco and sports industries ran scare campaigns claiming that Aussie sport was under threat. For example, when a West Australian MP proposed banning sport sponsorships, the industry bought full-page newspaper ads portending that ‘you might never see your heroes battle out International cricket at the WACA again’.b

But when the bans were finally implemented, other sponsors – including state government public health agencies – quickly jumped into the openings. Rugby League’s Winfield Cup became the Optus Cup; Ansett and Carlton & United Breweries took over the Benson & Hedges cricket series.c The total value of sports sponsorships grew by an average of 11 per cent per year in the three years after the ban was implemented in 1996.d

Similarly, there was no dip in total TV or radio advertising revenue when the tobacco ad ban was phased in between 1973 and 1976 (Figure 4.1).

a. A few state governments banned sponsorships before this, but federal law changed in 1992, and sponsorships were phased out by 1996: Greenhalgh et al (2024).

b. Tobacco Institute of Australia (1983).

c. Farrelly et al (1998); and Mitchell (2018).