Published by Inside Story, Wednesday 9 May

Scott Morrison was all smiles as he handed down his pre-election budget on Tuesday night. Economic good times — at least compared to forecasts — allowed him to announce income tax cuts and an early return to surplus while making very few difficult spending decisions. But the new medium-term target of capping taxes as a share of the economy will only be achievable with superhuman spending restraint: and both history and demographic forces will be against him.

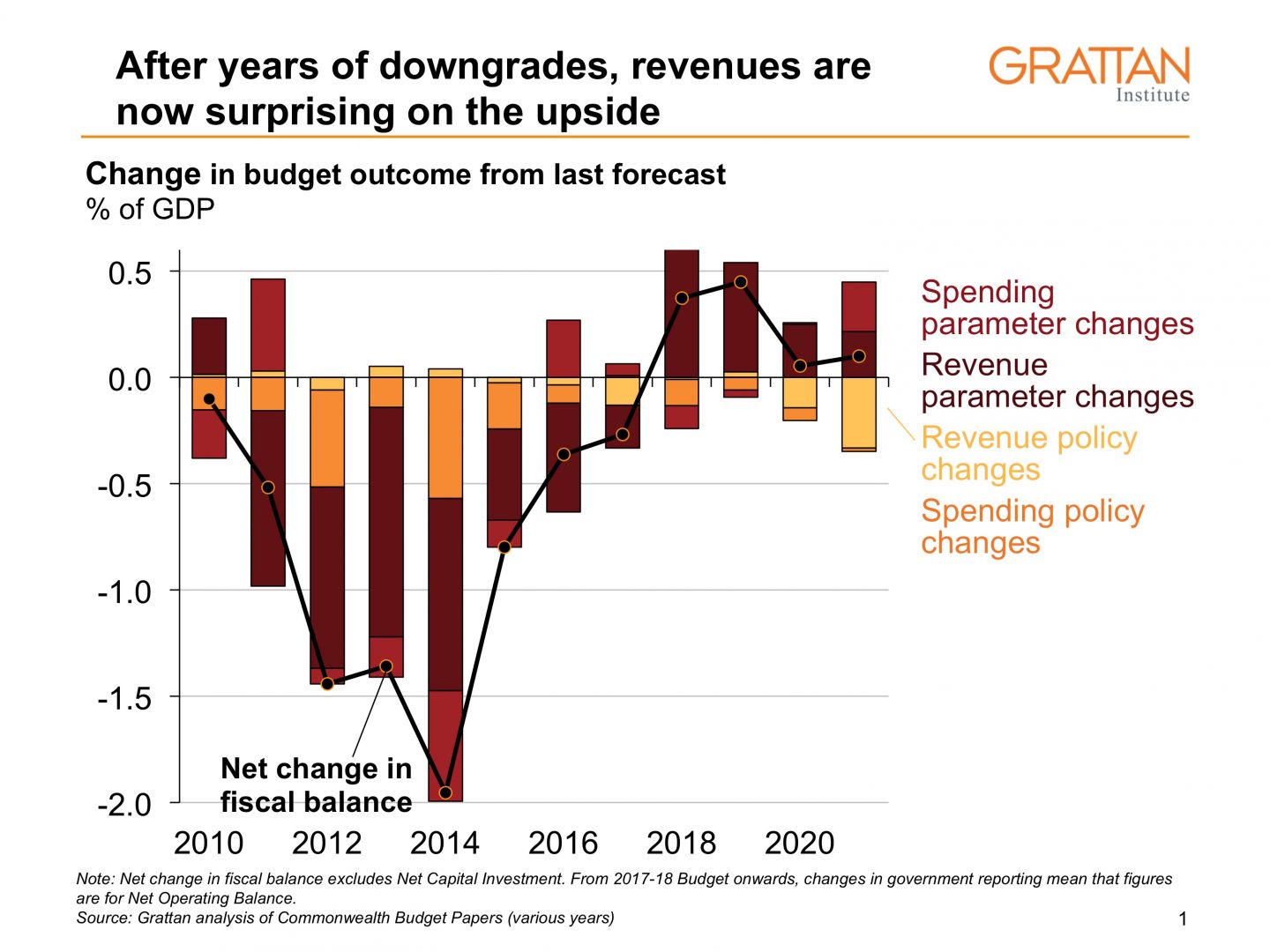

For the first time in years, a federal treasurer has had some luck in the lead-up to the budget. Over almost a decade, tax revenues have repeatedly fallen short of forecasts. But this year, tax receipts have exceeded expectations.

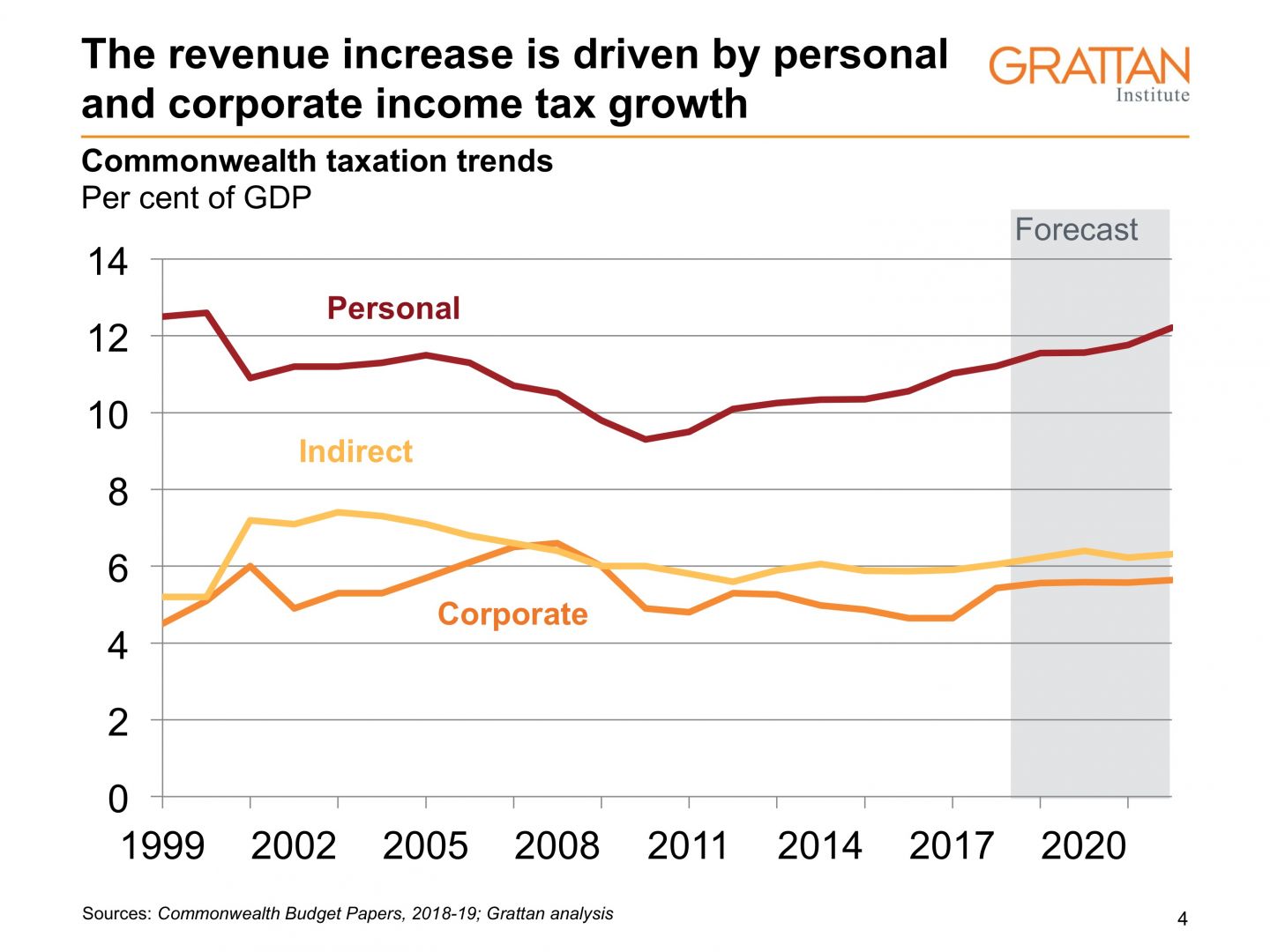

Total receipts are up $31.5 billion over the four years to 2021–22 compared to the mid-year update in December, driven by stronger personal and company tax receipts. Australian companies appear to have finally run out of tax-deductible losses from the 2008 global financial crisis and are suddenly paying far more tax. Wages are still stagnant, but personal income tax revenues have risen anyway as employment has increased, due in part to record migration. And with the world economy the best it’s been in years, there’s also good news in commodity prices, which feeds into higher company tax revenues in Australia.

All this good luck means Treasury now expects the budget to return to surplus in 2019–20, a year earlier than previously forecast. But the projected surplus in 2019–20 — of $2.2 billion, or just 0.1 per cent of GDP — hangs in the breeze. A more solid surplus of $11 billion (0.5 per cent of GDP) is expected in 2020-21, but that too still relies on the Treasurer staying lucky.

Basking in such good fortune, the treasurer plans to share it around. He will not proceed with the planned 0.5 per cent increase in the Medicare Levy to help pay for the National Disability Insurance Scheme. Most Australians will get tax cuts, starting on 1 July 2018 with the creation of a new low- and middle-income tax offset worth up to $530 a year; together with slight tweaks to the tax thresholds, this will deliver modest tax cuts of up to $665 a year to those earning between $20,200 and $125,000.

The government has also set out a radical plan to flatten Australia’s tax scales over the next eight years, including abolishing the 37 per cent tax bracket. By 2024–25 the vast majority of Australians will pay the same marginal tax rate of 32.5 per cent, for incomes starting at $41,000 all the way up to $200,000 a year. The tax cuts might favour low and middle-income earners in the short term, but high-income earners will be the beneficiaries in the long term.

Tax cuts were inevitable after a sustained run of bracket creep. Income taxes were closing in on the peaks of the late 1980s and the 1990s. But the size of the personal tax cuts — worth $4.5 billion by 2021–22 — and the decision to abandon the planned Medicare Levy increase leaves lots of room for Bill Shorten to offer his own basket of budget goodies in the budget reply speech on Thursday night.

Like all budgets, this one also has its share of fudges. But gone are unrealistic forecasts for nominal GDP and revenues, the fudges of budgets past. Instead projected budget surpluses, in spite of planned tax cuts, are built on herculean spending restraint. Spending is supposed to grow by a mere 0.7 per cent in 2020–21 and 0.5 per cent in 2020–21, after adjusting for inflation.

Given recent experience, such spending restraint looks wildly optimistic. After all, real spending grew by 2.7 per cent in 2017–18 and is projected to increase by 1.9 per cent in 2018–19. Health spending is projected to grow by just 1.9 per cent a year over the next five years, well below average growth of 3.8 per cent in the past five years. Meanwhile federal spending on courts, housing, agriculture and transport, are all forecast to fall in absolute terms between 2017–18 and 2021–22.

Reclassifying federal money for new transport infrastructure projects as “off-budget” capital spending also helps. This buy now, pay later approach has allowed successive governments to commit around $50 billion in infrastructure spending over the past decade — including on the NBN, Inland Rail, Western Sydney Airport and the Snowy Hydro share buyback — without any immediate hit to the budget bottom line. But if the numbers on these projects don’t stack up, future taxpayers will be on the hook for today’s bad decisions.

The budget forecasts for wages growth, driving much of the planned increase in personal income tax collections, also remain optimistic. Like the Reserve Bank, treasurer Scott Morrison is banking on strong growth in full-time employment translating into higher wages. Wages growth is expected to accelerate from just over 2 per cent a year today to 3.5 per cent by 2020–21.

And a plan to collect tax on tobacco at the border will bring forward $3.3 billion in tax revenue, providing a one-off boost in 2019–20, without which the government wouldn’t have achieved its early surplus.

Looking further ahead, the government is set to tie itself in knots with a plan to formally adopt a tax-to-GDP limit of 23.9 per cent, writing it into this year’s budget rules. The political logic is clear: to wedge Labor, which is relying on tax increases to pay for higher spending while still balancing the books.

But the inconvenient fact is that spending has averaged more than 25 per cent of GDP for the past decade. Non-tax receipts, worth 1.7 per cent of GDP in 2018–19, help bridge the gap between spending and tax revenues. But the government’s approach still relies on a strong economy and unprecedented spending restraint to keep spending down as a share of GDP. Most recent successful budget repair has occurred through tax increases, not spending cuts. Past attempts to bring down spending, such as those in the 2014–15 Budget, proved deeply unpopular. Many ended up languishing in the Senate, or were later abandoned.

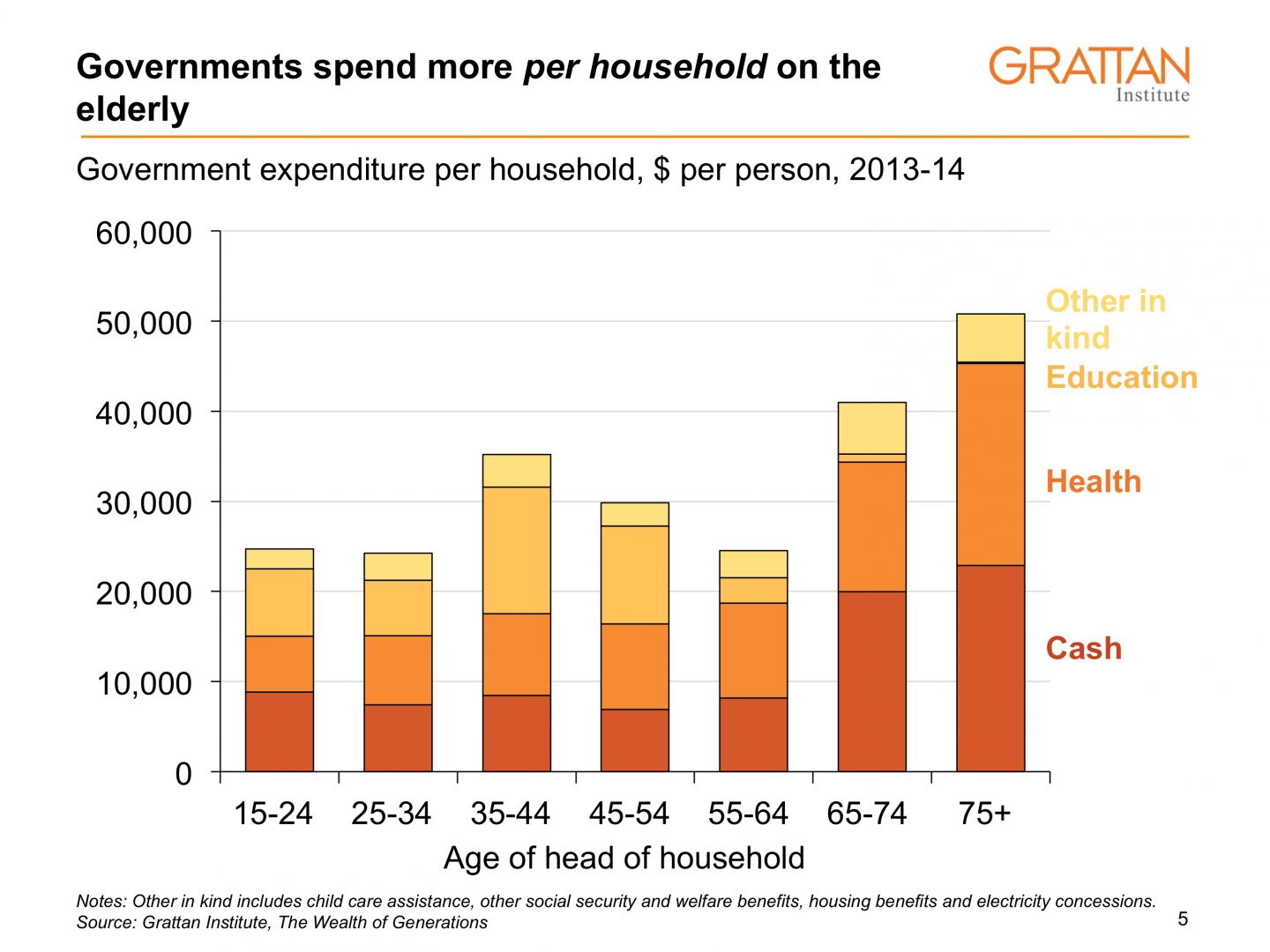

More importantly, the pledge to limit taxes to below 23.9 per cent of GDP is likely to crash headlong into the growing budgetary costs of Australia’s ageing population, as successive intergenerational reports have shown.

Spending per older household on health and the age pension has grown faster than the economy: governments already spend twice as much on each sixty-year-old as they do on each thirty-year-old. The 2015 intergenerational report showed Commonwealth health spending was projected to increase from 4.2 per cent of GDP in 2014–15 to 5.5 per cent of GDP in 2054–55.

The Coalition is unlikely cut back spending on health and education, especially with fresh memories of the “Mediscare” campaign from the last election. The planned increase in the pension eligibility age to seventy years — although worth pursuing — remains unlegislated. So the tax cap, combined with rising spending from an ageing population, is a recipe for ongoing budget deficits.

This is clearly a pre-election budget. Of course, the polls suggest the next budget is just as likely to be brought down by Labor’s Chris Bowen. Which means that Thursday night’s budget reply speech could prove just as important as last night’s announcements. And the contrast couldn’t be clearer. But the question is whether either side can make the numbers work over the longer term.