Published in The Conversation, 15 June 2020

Despite massive efforts by teachers and schools during the remote learning period, many students are likely to have learnt less than they would have in the classroom. Most of these students will recover without too much trouble, but disadvantaged students will need extra help.

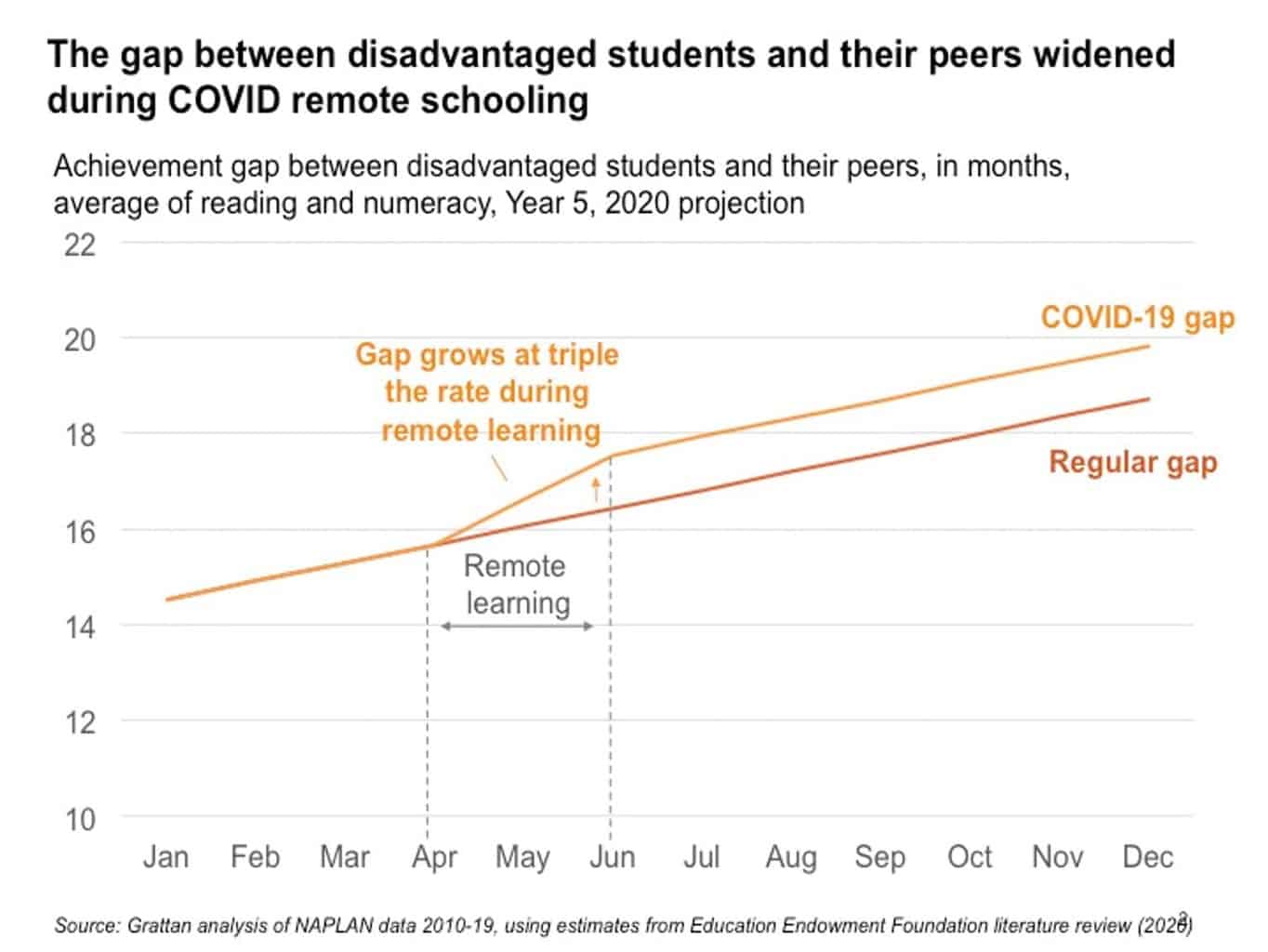

Our new report, COVID-19 catch-up: helping disadvantaged students close the equity gap, shows the achievement gap between disadvantaged and advantaged students widens at triple the rate in remote schooling compared to regular class.

Even if remote learning worked well, disadvantaged students are likely to have learnt at about 50% of their usual rate. This means they would have lost about one month of learning over two months of remote schooling.

The Morrison government has already committed an unprecedented A$134 billion to stimulate the economy, with more stimulus spending to come. Some should go to helping disadvantaged students catch up over the next six months.

How we made our estimates

We estimate around one in four students will need help to catch up on their learning. This is especially so for students who were already far behind, for whom the extra challenges of remote schooling are likely to have compounded existing inequalities.

This includes students from low socio-economic families, Indigenous backgrounds and remote communities, as well as students experiencing poor mental health.

Our estimates of how far behind disadvantaged students may have fallen during the remote period are only a rough indication. But they are based on a significant review of various studies on learning disruption, led by the UK Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) in May.

The EEF searched literature across a variety of scenarios that cause school disruptions including hurricanes, bushfires, summer holidays and teacher strikes. While summer holidays are different to remote schooling, they are relevant because they isolate the influence of the home on a student’s performance.

The findings from these studies show during the US summer vacation, a gap of up to three months in learning opens up between disadvantaged students and their peers. Disadvantaged students return to school being much further behind their peers than when holidays began.

Why disadvantaged students lose out

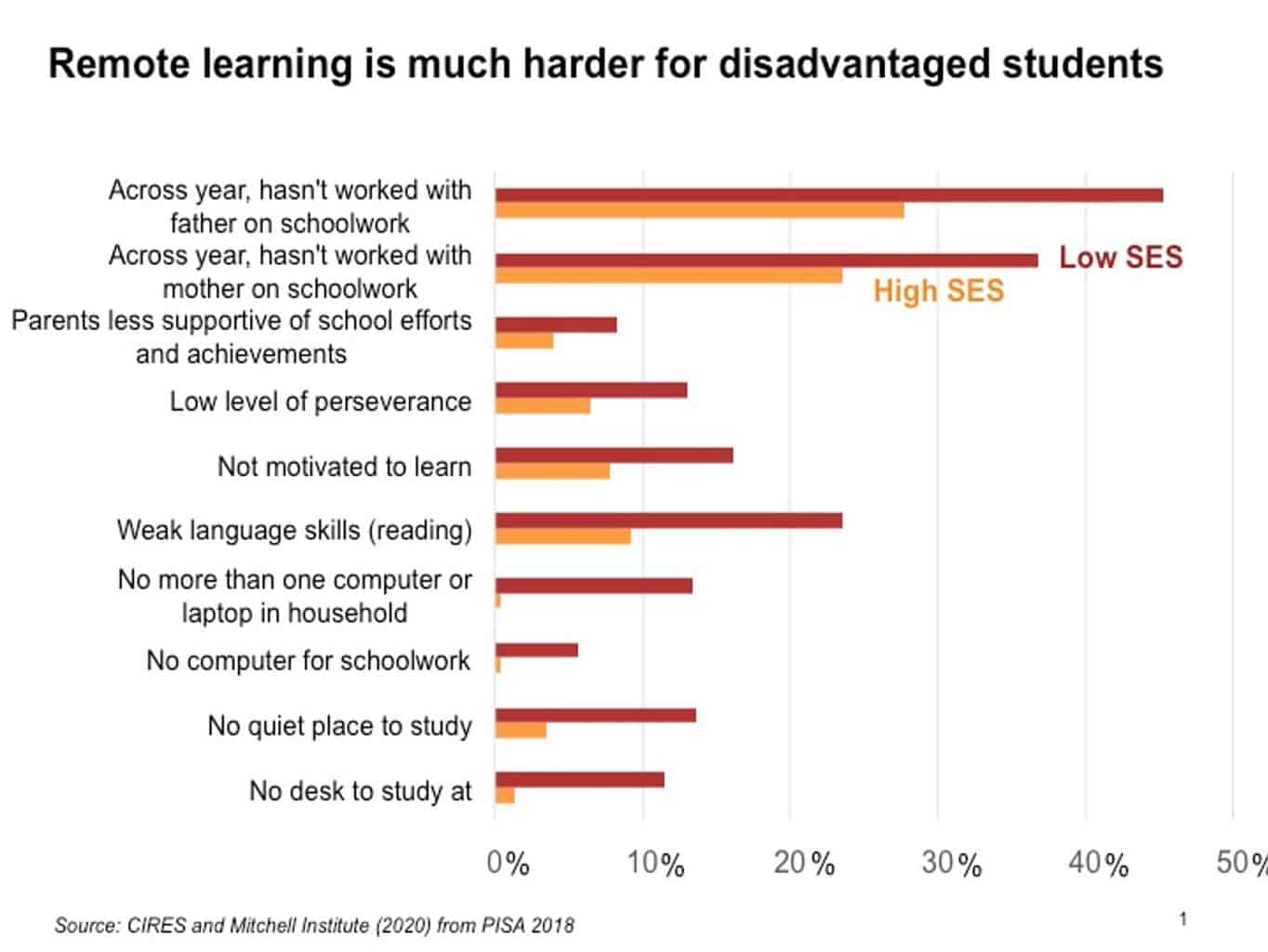

There are many reasons disadvantaged students are hit hardest by remote schooling, as the chart below shows. They tend to get less help with school work from their parents. They are less likely to have a computer, good internet service, and a desk or quiet place to study.

Disadvantaged students, on average, are also likely to be behind in their learning, making it harder to work independently.

The existing achievement gap is more than ten times greater than the gap that will have developed during the COVID-19 disruptions, as shown the chart below.

The recession will only make things harder, because disadvantaged students are more likely to have to deal with the emotional and financial stresses of a parent losing income or a job.

What the government can do: put stimulus funding toward disadvantaged students

Governments are now spending big to stimulate the economy. The World Bank believes COVID-19 has sparked the worst global recession since at least the second world war.

COVID-19 and the economic downturn offers a big opportunity for a national investment in education. We recommend a recovery package of A$1.2 billion targeted at vulnerable students for the next six months. This will help one million students, around one in four, recover the learning lost during COVID.

The money should be spent on two high-priority initiatives.

First, $1 billion should go towards helping large numbers of struggling students access small-group tutoring. Tutoring would be delivered in groups of about three students, either in or outside classes, three or four times a week over a 12-week period.

Evidence shows small group tuition can boost student learning by five months over one or two terms of schooling.

Young university graduates and student teachers should be hired as tutors where possible – given young people will be hit harder by the recession than older Australians and are likely to spend the extra income quickly.

Second, we recommend investing $70 million in successful literacy and numeracy programs which can improve student learning by three or more months. For example teaching reading using synthetic phonics, as well as reading comprehension strategies and oral language interventions.

These are a priority for the early years, so students have the foundations for future learning.

We also suggest extra support for students to improve both well-being and learning. There is less evidence on what works in this area, but we suggest small trials in promising areas, such as extra training for teachers in mental health literacy and supporting students’ social skills, as well as extra resources for targeted behaviour supports.

To ensure the students who most need help are accurately identified in the first place, we recommend the national assessment body – the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority – create a A$20 million package of suitable in-class assessment tools. The right support depends on pinpointing student needs.

While costing a little over $1 billion, our suggested reform package would deliver about $3.5 billion in extra future earnings for disadvantaged students, given better results at school leads to better employment and income prospects in later life.

This reform package offers an important opportunity to trial and evaluate what works, to inform longer-term efforts to close the bigger existing equity gap.

![]()