Published in John Menadue – Pearls and Irritations, April 30 2020

The sight of Centrelink queues snaking around the block past shuttered shopfronts in cities, suburbs, and towns across Australia leaves no doubt that COVID-19 is having a big impact on Australian unemployment. But just how big?

In our new working paper, Shutdown: estimating the COVID-19 employment shock, we calculate that between 14 and 26 per cent of Australian workers – 1.9-to-3.4 million people – could be out of work as a direct result of the enforced social or ‘spatial’ distancing.

We estimate the likelihood of a particular job being lost based on the industry, and whether the job requires physical proximity to other people. On our numbers, more than half of all hospitality workers could be out of a job. Many working in retail trade, education and training and the arts are at risk. Even one-quarter of health workers could lose their livelihoods: while doctors and nurses may be run off their feet in hospitals, physiotherapists and dental practices sit idle.

Our political leaders like to say that ‘we’re all in this together’. But some of us are paying a much bigger price than others. Lower-income workers are twice as likely to lose their jobs as high-income earners. Younger Australians and women are also likely to be hit harder, because they tend to work in jobs and industries that require them to be in close physical proximity to fellow workers or the public.

Governments are seeking to cushion the blow. The Federal Government has already committed to spending around $200 billion, or almost 10 per cent of annual GDP, to help business and households through the crisis. The cornerstone is the $130 billion JobKeeper wage subsidy of $1,500 a fortnight. It’s not perfect: temporary migrants and short-term casuals should be included. But it does gives Australia a fighting chance of avoiding the worst of the economic fallout.

Unemployment will still rise steeply in the coming months, but JobKeeper will obscure much of the impact. Many out-of-work Australians will still be counted as ‘employed’ because they’ll still be paid by their employers. Others will give up trying to find a job entirely, and so won’t be counted among the unemployed either. Treasury expects the official unemployment rate to rise to 10 per cent in the coming months. On our numbers, it could go as high as 12 to 15 per cent.

And while the short-term economic hit from the shutdown is bad enough, there could be worse to follow. Prime Minister Scott Morrison talks of the budget ‘snapping back’ on the other side of the COVID-19 crisis. But the prospects of a ‘V-shaped’ recovery are remote.

Firms and households not directly affected by the shutdown are scaling back spending to preserve cash flow in case an extended downturn. Both consumer and business confidence have crashed to their lowest levels on record.

But a cursory reading of the COVID-19 strategies of most advanced nations suggests life won’t return to normal anytime soon. Even if we manage to eradicate the virus in Australia, most other countries won’t be so lucky. That means our government’s economic support will probably have to remain in place for much longer than six months – and that still more spending will be needed.

The COVID-19 economic crisis is unique: the public health crisis demands shutting down broad swathes of the economy to slow the spread of the virus, but when the public health threat eventually declines, policymakers will be left to deal with a more traditional demand-side recession. At that point, Australian governments should stand ready to inject substantial fiscal stimulus to boost aggregate demand, as they did so successfully during the Global Financial Crisis.

The budgetary cost of such unprecedented spending naturally raises concerns about the burden rising debt will place on younger generations. But younger generations are also bearing most of the economic costs of the shutdown: they are more likely to have lost their jobs. And if the government refuses to spend more, younger generations will also bear the long-term costs of a severe and prolonged recession.

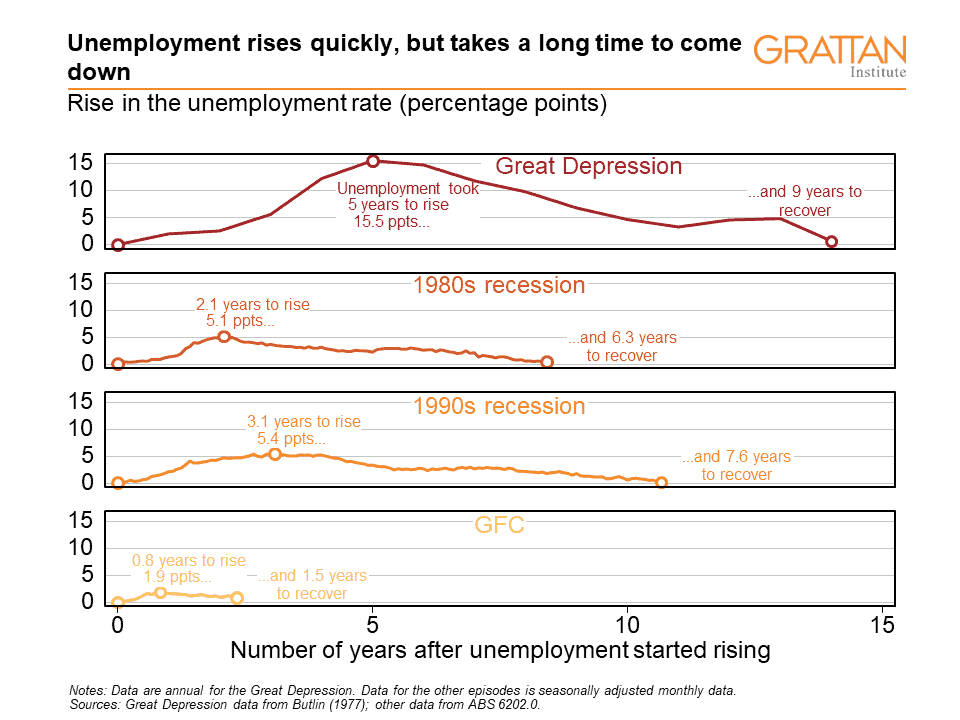

History tells us that the economic costs of recessions are long-lasting. In the 1990s recession, it took three years for the unemployment rate to reach its peak, but nearly eight years to return to its pre-recession level. Younger workers carried the scars for years via lower earnings. Many older Australians never worked again. The longer this downturn goes, and the worse it gets, the less likely the labour market can spring back afterwards.

Ultimately the economic challenge of COVID-19 underscores the importance of getting the virus under control. Resolving the public health crisis is a critical first step on any path to sustained economic recovery. If we want to see Australians back at work, we have to solve that first.