The Albanese Government has committed to raising the Temporary Skilled Migration Income Threshold (TSMIT), which puts a floor under the wage at which employers can sponsor workers to Australia via the Temporary Skill Shortage visa.

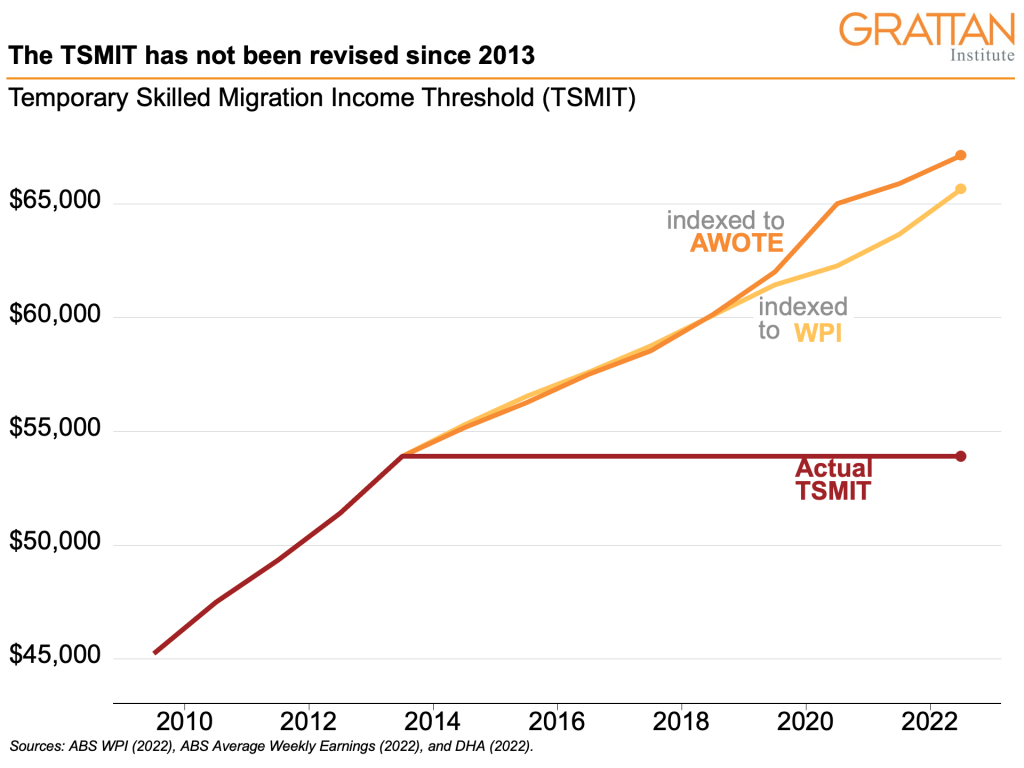

Everyone seems to agree that the so-called TSMIT is too low and should be raised. It hasn’t been increased since 2013, and at $53,900 a year is now lower than the wages earned by 80 per cent of Australia’s full-time workers. Freezing the TSMIT has allowed employers to sponsor a growing number of low-wage workers with fewer skills – half of all Temporary Skill Shortage visa-holders earn less than the median full-time income, compared to just 38 per cent 15 years ago.

But the big question for the federal government is, how high should the TSMIT be? The ACTU wants it raised to $90,000. The Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry also wants it lifted, but only to $60,000. The Grattan Institute suggests a threshold of $70,000 – roughly where it would have been if it had been indexed to wages over the past decade.

Here’s why we think $70,000 is the Goldilocks threshold – not too low and not too high.

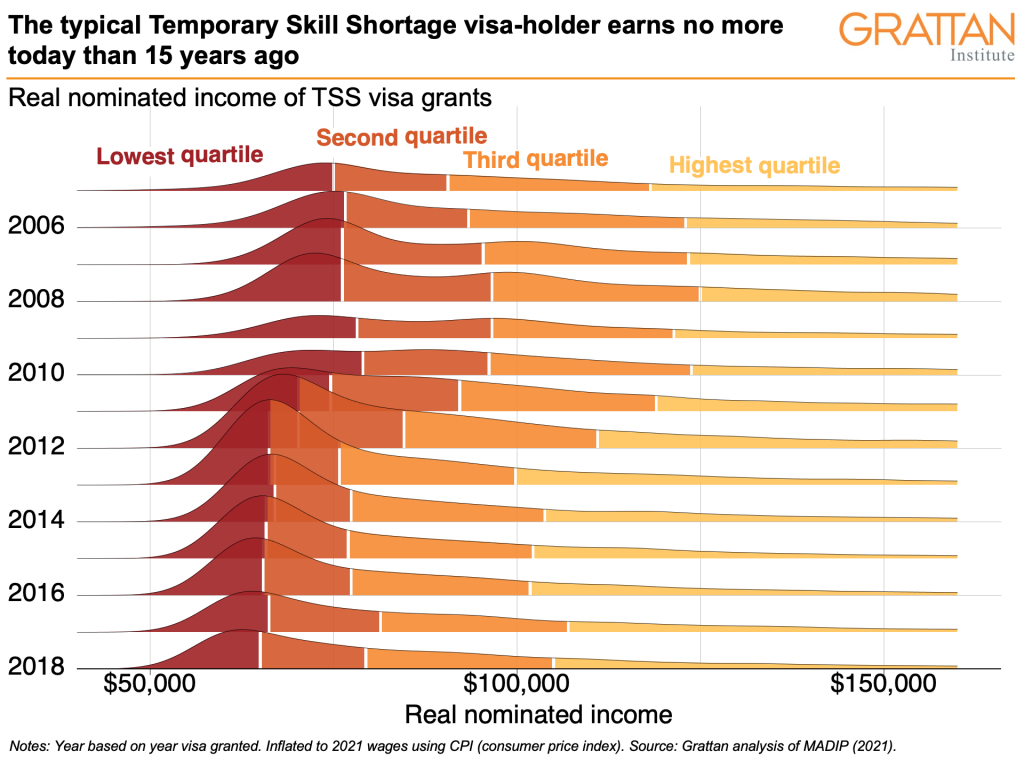

Firstly, $60,000 is too low, because the wage threshold needs to reflect the fact that the temporary skilled program is, as the name suggests, a program for skilled migrants. Yet in the years since the TSMIT was frozen, more and more low-wage workers have come to Australia, notably in sectors such as retail and hospitality. The typical Temporary Skill Shortage visa-holder earns no more today than they did 15 years ago, despite the wages of the average full-time Australian worker rising by about 20 per cent above inflation in that time.[1]

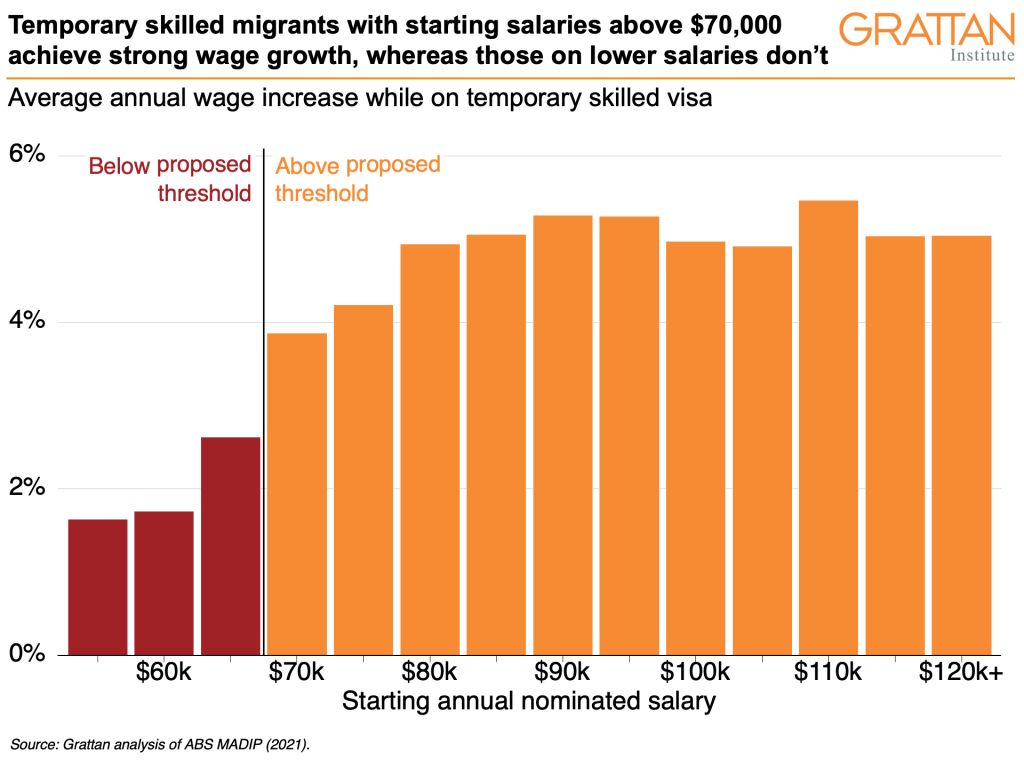

One big problem with a too-low threshold is that lower-wage migrants are vulnerable to exploitation. Grattan Institute research indicates that sponsored migrants on temporary visas who earn $70,000 or less on arrival get few or no pay rises, whereas those who start out on more than $70,000 tend to get big pay rises – more than 5 per cent a year on average over the time they hold a Temporary Skill Shortage visa in Australia. This suggests that migrants earning more than $70,000 have more bargaining power than migrants earning less than that.

So, letting migrants into Australia on wages below $70,000 without appropriate safeguards risks the continued exploitation that we already see among low-wage temporary skilled visa-holders.

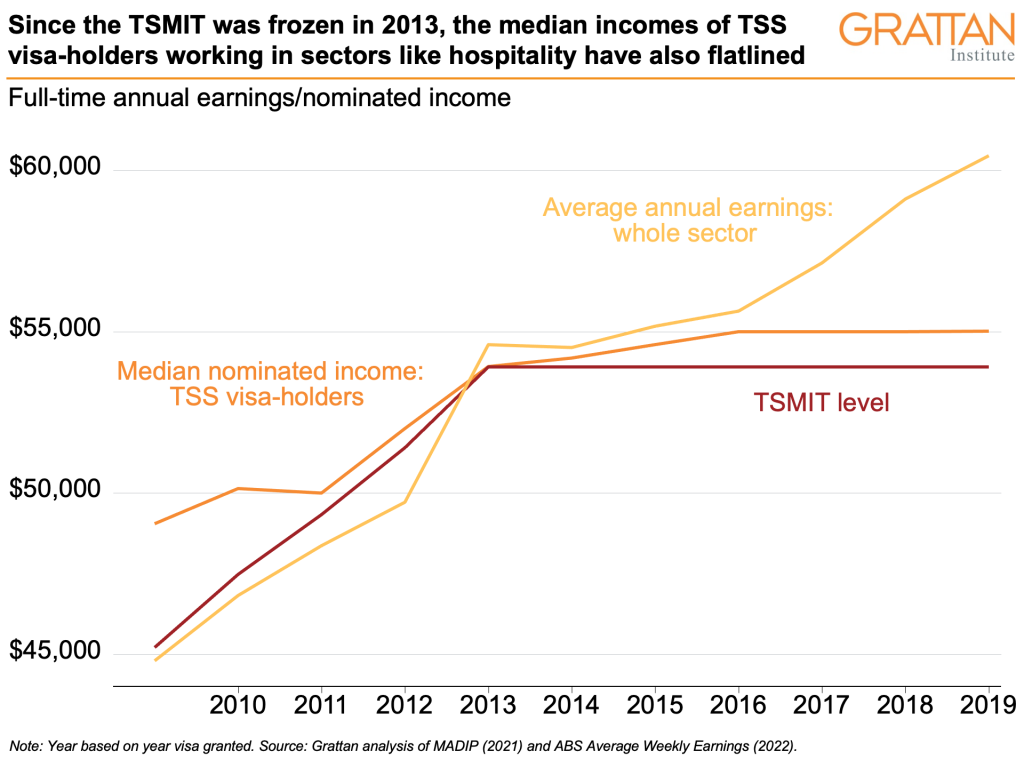

In fact, freezing the TSMIT appears to have put downward pressure on the wages earnt by Temporary Skill Shortage (TSS) visa-holders. The wages of TSS visa-holders working in hospitality have flatlined since the TSMIT was frozen in 2013, whereas the wages of Australian workers in the same sector have continued to rise.

A $90,000 threshold is too high

But on the other hand, the $90,000-a-year threshold proposed by the ACTU and economist Ross Garnaut is too high. Here’s why.

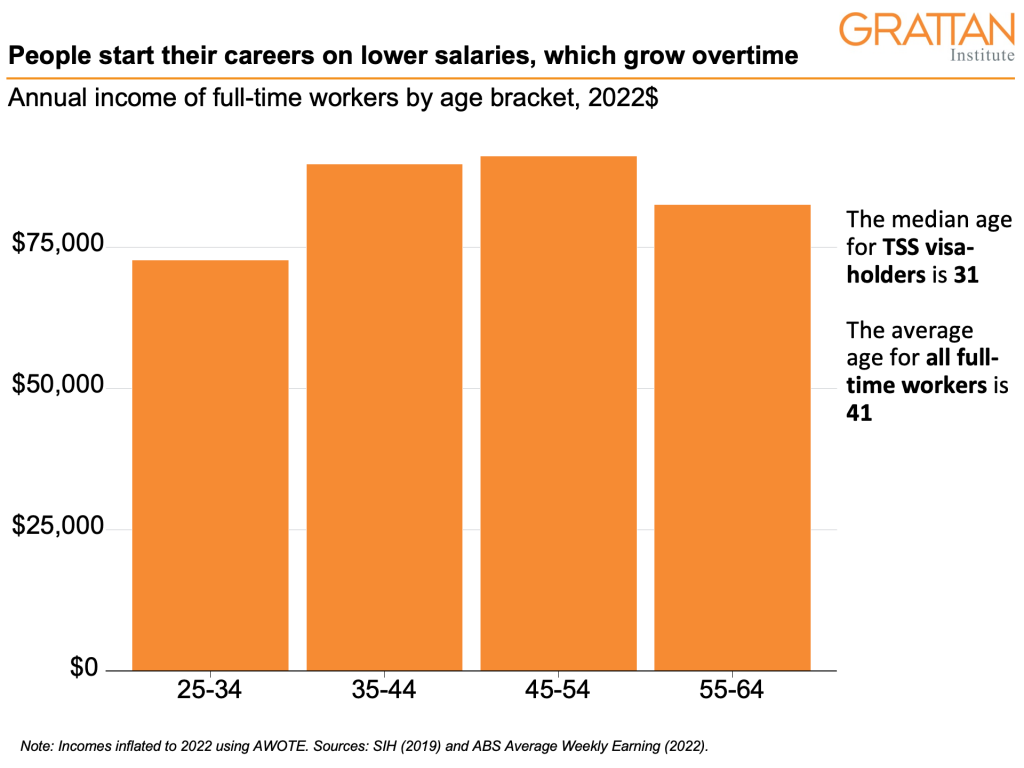

Temporary skilled visa-holders are often young – the typical TSS visa-holder is 31 years old – and therefore in the early stages of their career. The median full-time wage for Australian workers aged 25-34 is $72,774 a year. By contrast, $90,000 is around the average full-time earnings of a person in the Australian workforce, but that average person is about 40 years old and halfway through their career.

Setting the TSMIT at $90,000 would cut out many of the younger skilled workers who start out earning lower-than-average wages but form the backbone of Australia’s permanent skilled migrant intake and earn much higher wages in the long term. After all, one quarter of all permanent skilled visas, and 90 per cent of permanent employer-sponsored visas, go to migrants currently in Australia on a TSS visa.

Grattan Institute’s 2021 report, Rethinking permanent skilled migration after the pandemic, showed that migrants on permanent employer-sponsored visas are Australia’s most successful skilled migrants, earning more than migrants who come via any other visa stream.[2] Raising the TSMIT to $90,000 a year would cut Australia off from many younger skilled migrants who would otherwise make a big contribution to Australia.[3]

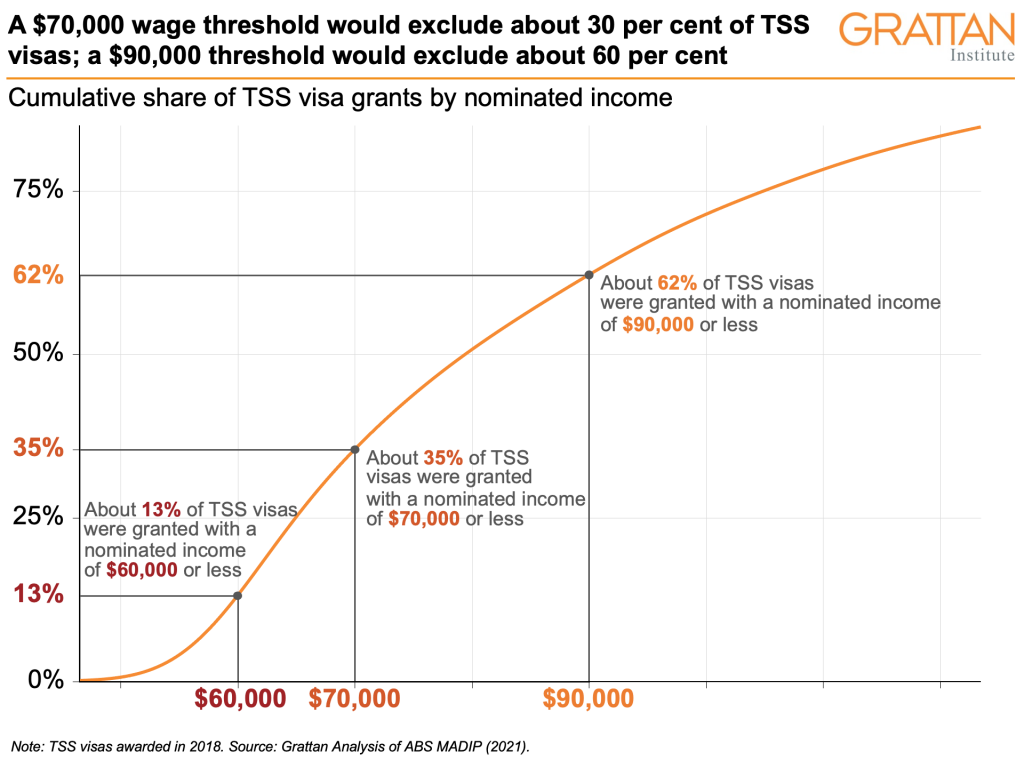

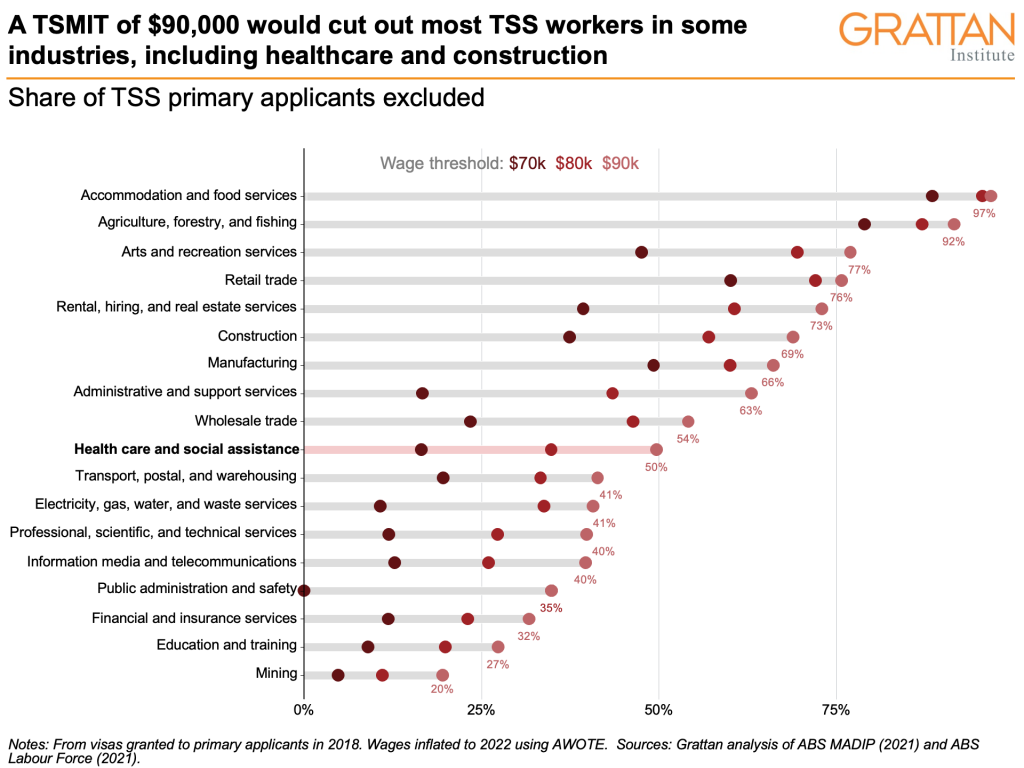

Setting the TSMIT too high would also risk locking out large numbers of the skilled workers Australia desperately needs right now. A $90,000-a-year threshold would have excluded about 60 per cent of recent TSS visas granted, including up to half of all healthcare workers on TSS visas and one-third of all education workers on TSS visas. In particular, a $90,000 threshold would exclude up to 89 per cent of nurses currently working in Australia on temporary sponsorship.

By contrast, our preferred $70,000 threshold would lock out only about 35 per cent of all TSS visa-holders, and less than 20 per cent of sponsored workers in healthcare.

A higher TSMIT will inevitably involve some disruption for some businesses

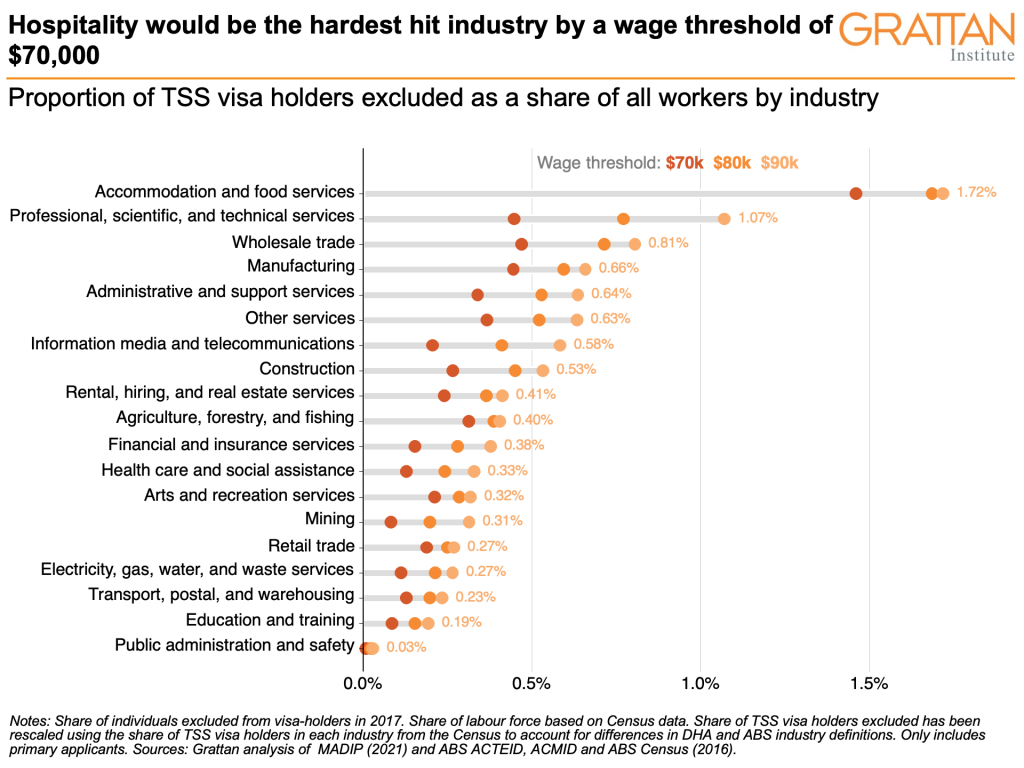

A $70,000 threshold would still result in many sponsored workers in low-wage sectors such as hospitality and retail being excluded, but these are precisely the workers who are at greatest risk of exploitation and get little wage growth in Australia, including once they are granted permanent residency.[4] Continuing exploitation threatens public support, not just of temporary skilled migration but of migration more broadly.

And those visa-holders locked out by a $70,000 wage threshold would account for only a small share of all workers – less than 1 in every 200 workers in all sectors other than hospitality. And in practice at least some sponsoring employers would raise the wages they pay to maintain access to temporary migrants, as they appeared to be before the TSMIT was frozen in 2013.

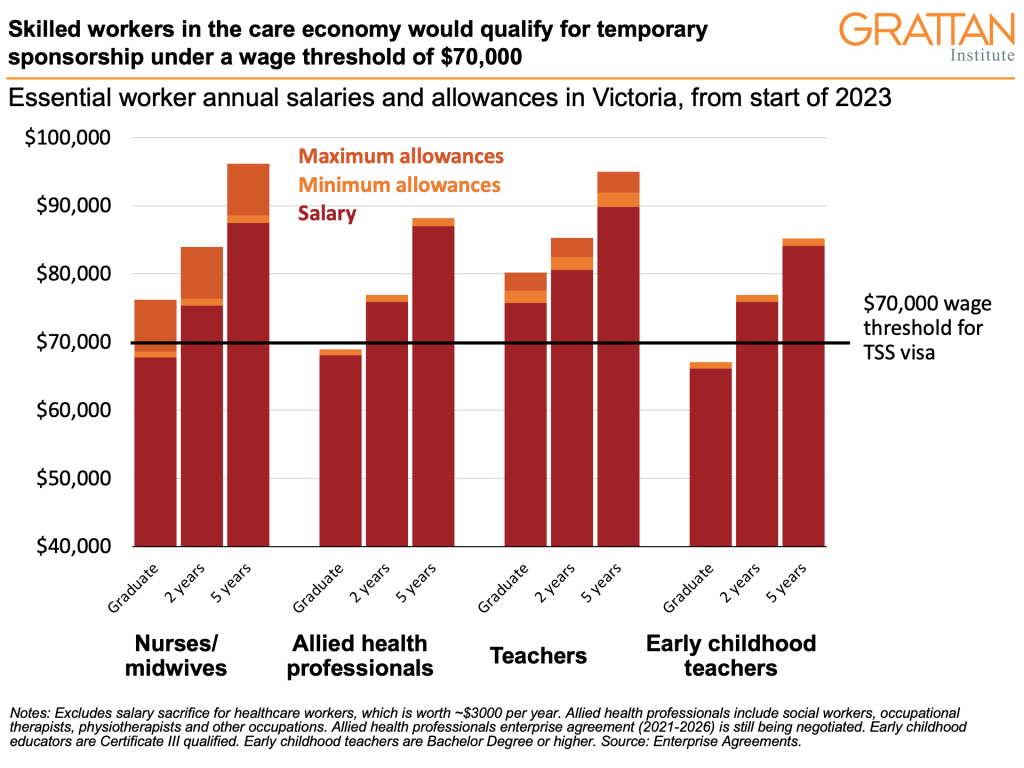

Skilled workers such as nurses, school and kindergarten teachers, and allied health professionals such as physiotherapists would still qualify for temporary sponsorship under a $70,000 wage threshold, including once they have two years of experience – the minimum to qualify for a TSS visa in the first place.

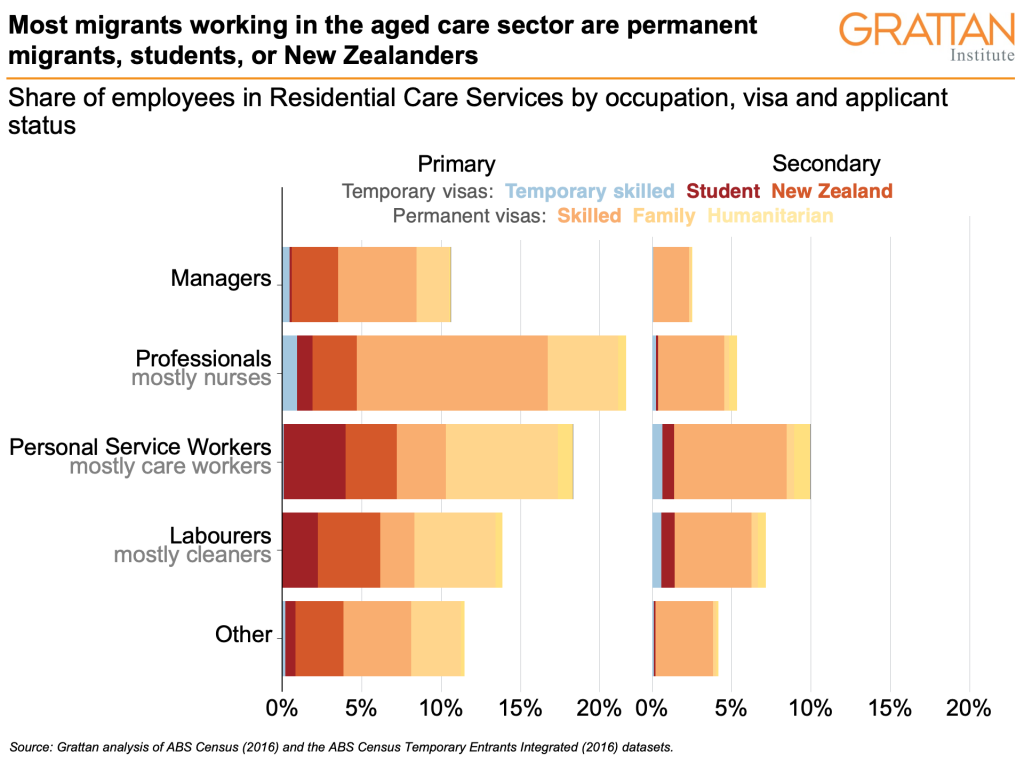

And a $70,000 wage threshold would have little impact on sectors such as aged care. While workers on temporary and permanent visas account for about 30 per cent of care workers in aged care, less than 1 per cent are sponsored by employers for the purposes of work.

That’s because low-wage jobs such as carers and cleaners are not eligible for temporary sponsorship today. After all, personal care attendants in residential aged care start out earning just $43,000 a year – a wage level 20 per cent below the existing TSMIT. Instead, the vast bulk of migrants working in lower-wage jobs in aged care are students and permanent residents.[5] And higher-wage aged care jobs such as managers and nurses tend to be paid more than $70,000 a year and would remain eligible for temporary sponsorship.

Exclusively targeting temporary sponsorship to higher-wage workers – who are at much less risk of exploitation – would also mean sponsorship could be simplified for employers. For instance, rules for accrediting sponsoring employers could be relaxed and labour market testing scrapped. This could result in sponsors of high-wage migrants having visa applications granted in as little as two weeks.[6]

We therefore believe $70,000 is the Goldilocks threshold, for four reasons. It would strengthen the integrity of the temporary skilled migration program by making sure the program is indeed available only to skilled workers. It would lower the risk of exploitation by preventing businesses from hiring vulnerable migrants with less bargaining power. It would ensure we continue to attract younger, skilled workers to Australia via temporary sponsorship who become high-earning permanent migrants in future. And by allowing sponsorship only of higher-wage workers, Australia could simplify sponsorship rules for both employers and migrants, making sponsorship much more attractive.

Footnotes

- See Fixing Temporary Skilled Migration: a better deal for Australia, Figure 1.5.

- Recent permanent employer-sponsored migrants typically earn between $10,000 and $20,000 a year more than migrants granted points-tested visas. Treasury has previously estimated that each permanent employer-sponsored visa-holder offers a fiscal dividend of $560,000 over their lifetimes in Australia, more than visa-holders in any other visa stream.

- Alternatively, to reflect the lower wages earned by younger skilled workers, the federal government could set separate the TSMIT at different levels for workers of different ages. For instance, it could retain a $70,000 wage threshold for workers aged below 35 years, and a higher wage threshold for workers aged 35-44 years who should reasonably be expected to earn more if they are genuinely skilled.

- More than half of all sponsored workers in accommodation and food services and retail trade get nominal wage rises of less than 2 per cent a year while on temporary sponsored visas. And workers in some occupations, such as food trades workers, see their wages fall on average once granted permanent residency. See Fixing temporary skilled migration: a better deal for Australia, Figure 2.5.

- See our 2022 report, Migrants in the Australian workforce, Section 5.4.

- See Fixing temporary skilled migration: a better deal for Australia, pp. 61 and 62.

Brendan Coates

While you’re here…

Grattan Institute is an independent not-for-profit think tank. We don’t take money from political parties or vested interests. Yet we believe in free access to information. All our research is available online, so that more people can benefit from our work.

Which is why we rely on donations from readers like you, so that we can continue our nation-changing research without fear or favour. Your support enables Grattan to improve the lives of all Australians.

Donate now.

Danielle Wood – CEO