Published at The Conversation, Wednesday 31 October

House prices might now be falling, but Australians’ anxiety over housing affordability is not. Price falls of a few percentage points in Sydney and Melbourne are cold comfort to first home buyers. They are still paying 50% more than they would have five years ago.

Further price falls are likely, but even then housing will still be less affordable than it was two decades ago.

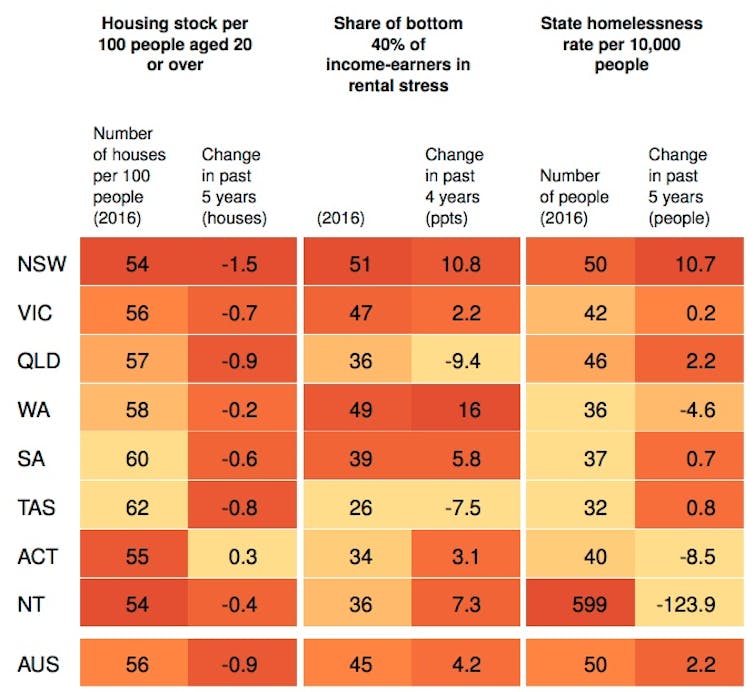

Home ownership rates are declining across Australia, especially among the young and the poor. An increasing proportion of low-income earners are in rental stress in all states except Queensland and Tasmania.

State housing scorecard

Grattan Institute State Orange Book 2018, Table 5.1

The required policy response remains the same. As Grattan Institute’s State Orange Book 2018 shows, state governments need to ensure a lot more housing is built.

What has happened to housing?

Australia’s population is growing rapidly. Our cities have not kept up, so there is less housing per person. The primary obstacle appears to be planning rules that delay or prevent development.

All states except Tasmania have less housing per person than a decade ago

Grattan Institute State Orange Book 2018, Figure 5.1

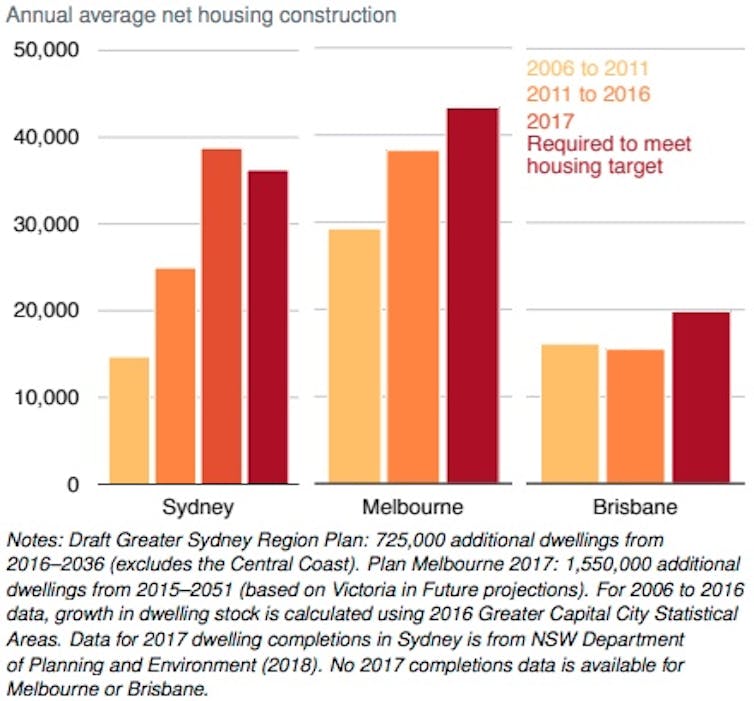

The New South Wales, Victorian and Queensland governments have all changed planning rules and processes over the past five years or so. This has resulted in new building finally catching up with population growth, even if a significant backlog remains.

The extra supply has already contributed to flattening rents and falling apartment prices in Brisbane. It will help push rents and prices lower in Sydney and Melbourne as well.

But today’s record level of housing construction is the bare minimum needed to match rapid population growth largely driven by immigration.

And yet authorities in NSW and Queensland are responding to NIMBY pressures by making it harder to increase density. In the Victorian election campaign, Opposition Leader Matthew Guy is promising to do the same.

Record housing construction will need to be maintained to meet city plan housing targets

Grattan Institute State Orange Book 2018, Figure 5.2

What should governments do?

Resisting higher-density development is the wrong response. To enable more homes to be built in inner and middle-ring suburbs of our largest cities, state governments should.

1.Introduce a new small redevelopment housing code. It would protect neighbours, reduce planning uncertainty and improve the quality of new developments. The code would include the things that worry neighbours the most, such as privacy, height and overshadowing.

2.Allow taller developments of four to eight storeys “as of right” on major transport corridors and around train stations.

3.Set housing targets for each local council. The targets should be linked to plans for the growth of the city as a whole. Where councils fail to meet planning targets, independent planning panels should step in.

The best evidence is that building an extra 50,000 homes a year for a decade could leave Australian house prices 5-20% lower than what they would have been otherwise, stem rising public anxiety about housing affordability, and increase economic growth.

Reform tenancy rules

As well as boosting supply, state governments should make renting more attractive by changing residential tenancy laws to increase the security of renters and help renters make their property feel like their home. The Victorian government recently tipped the balance more towards tenants. Other state governments should follow suit.

Of course, changes in tenancy laws in favour of renters could reduce the supply of rental housing and increase rents, but any such effects are likely to be vanishingly small. More likely some investors will sell their properties to first home buyers, which means one less rental property and one less renter.

Boost the public housing supply

The housing affordability crisis has made life particularly hard for low-income earners. There is a powerful case for extra public support for the most vulnerable Australians. But not all policies will be equally effective.

Boosting social housing will be expensive. Increasing the stock by 100,000 dwellings – broadly sufficient to return social housing to its historical share of the total housing stock – would require extra public funding of around A$900 million a year, or an upfront capital cost of between A$10 billion and A$15 billion.

Even then social housing would house only one-third of the poorest 20% of Australians. Most low-income Australians would remain in the private rental market.

The big problem is that there is not enough “flow” of social housing available for people whose lives take a big turn for the worse. Tenants generally take a long time to leave social housing; most have stayed more than five years

To overcome these issues, governments should build more social housing, and tightly target it to people most at risk of becoming homeless for the long term. Extra support for the housing costs of low-income earners should otherwise be delivered primarily by boosting Commonwealth Rent Assistance.

Stop offering false hope

State governments also need to stop offering false hope. Even though policies such as first home owners’ grants have proved ineffective time after time, they were the centrepieces of the housing plans of NSW and Victoria announced last year. Inevitably these are really second home sellers’ incentives: the biggest winners are people who own homes already, and property developers with new homes ready to sell.

Similarly, state governments shouldn’t claim that housing and business incentives and regional transport projects will divert a lot of population growth to the regions. Such policies haven’t made much difference in the past. And they provide excuses not to make the tough calls on planning.

None of the policies recommended in our State Orange Book 2018 are easy politically. But Australians need to face up to a harsh truth: either people accept greater density in their suburb, or their children will not be able to buy a home.

![]()