Published at The Conversation, 29 March 2021

Single parents with dependent children — eight out of ten of them women — were far more likely than others to lose work at the height of the pandemic and are far more likely to still be out of work now.

Even before COVID, many were in financial distress.

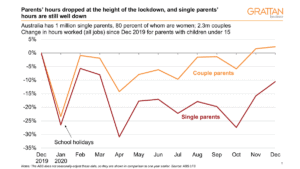

Single parents’ paid hours fell more than 30% in the depths of the crisis in April.

By December, even though there were no significant restrictions in place anywhere in Australia, paid hours for single parents remained 10% lower than they had been a year earlier.

This was at a time when the hours worked by couple parents had recovered quickly, and was higher than a year earlier.

Employment for single parents fell more than 10% between December 2019 and September 2020, and is still 5% lower than in December 2019.

About 50,000 single parents dropped out of the workforce altogether during the first lockdown – 11% of all single parents.

Why was the COVID recession so bad for single parents?

Many single parents had no choice but to stop working

One reason would be that the loss of formal and informal childcare and the need to manage remote learning meant many single parents had little choice but to stop working.

Also, single parents would be over-represented in the job-loss figures because they are over-represented in insecure work.

In August 2019, a quarter of single parents held casual jobs without paid leave. These jobs – many of them in COVID-vulnerable sectors such as retail and hospitality – were among the first to be lost during the lockdowns.

Many more were in casual jobs, ineligible for JobKeeper

Importantly, more than half of single parents in casual jobs had been in those particular jobs for less than a year, meaning the rules made them ineligible for JobKeeper support.

In a survey by the Melbourne Institute, only 13% of single mothers reported that they were receiving JobKeeper in late 2020, compared to 18% of mothers in couples and 33% of fathers in couples.

The outsized impact of the COVID recession on single parents is even more of a concern when we consider that they were among the most disadvantaged Australians before COVID.

Many had already been stripped of payments

In 2018, a third of single-parent families were living in poverty (compared to less than 10% of couples with dependent children). One fifth of single parents reported that they regularly skipped buying essential items.

And incomes for single parents were falling even before the crisis: between 2016 and 2018, when the national median annual income increased from $48,360 to $49,805, the median for single parents fell from $38,000 to $34,000.

Decisions by successive governments have contributed to this outcome.

From 2006, the Howard government’s Welfare to Work program pushed new single parents claiming income support onto the Newstart unemployment benefit – $87 per week less than the Single Parenting Payment – if their youngest was eight or older.

The decision pushed about 20,000 single parents on to a lower payment.

In 2013, the Gillard government pushed another 80,000 single parents onto Newstart by extending the policy to single parents who had been claiming parenting payments before 2006, almost doubling the proportion of single parents in poverty, lifting it to 59%.

After Welfare to Work came ParentsNext

Then in 2016, the Turnbull government launched ParentsNext, with the stated intention of helping single parents with children as young as six months to return to work.

It included so-called participation plans, under which parents could be stripped of payments unless they performed mandated activities – for example, taking their child to swimming lessons.

A Senate inquiry recommended it “not continue in its current form”. Instead the 2020 budget set aside $24.7 million to “streamline the successful ParentsNext program”.

The COVID crisis and a series of government decisions before that are condemning hundreds of thousands of Australian children to growing up in poverty, and exacerbates intergenerational disadvantage.

Here are three things governments could do to make a difference:

- Significantly increase in the permanent rate of JobSeeker. This would make a huge difference for unemployed single parents with children aged eight or older who thanks to earlier government decisions have to rely on JobSeeker while they make the transition to work. The Federal Government plans to increase the permanent rate of JobSeeker by $25 a week.

- Make childcare cheaper. This would help single parents get back into paid work sooner and expand opportunities for early education for their children. Cost is the major barrier for families wanting childcare. The Grattan Institute has identified a series of options to improve affordability.

- Classify single parents in the workforce as “essential workers” for the purposes of any future lockdowns. This would mean their children could continue going to school and childcare.

These changes would help single parents raising the adults of the future, who are at risk of slipping further behind.

![]()